|

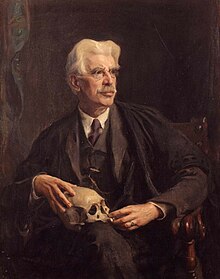

Alfred Cort Haddon

Alfred Cort Haddon, Sc.D., FRS,[1] FRGS FRAI (24 May 1855 – 20 April 1940) was an influential British anthropologist and ethnologist. Initially a biologist, who achieved his most notable fieldwork, with W. H. R. Rivers, Charles Gabriel Seligman and Sidney Ray on the Torres Strait Islands. He returned to Christ's College, Cambridge, where he had been an undergraduate, and effectively founded the School of Anthropology. Haddon was a major influence on the work of the American ethnologist Caroline Furness Jayne.[2] In 2011, Haddon's 1898 The Recordings of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits were added to the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia's Sounds of Australia registry.[3] The original recordings are housed at the British Library[4] and many have been made available online.[5] Early lifeAlfred Cort Haddon was born on 24 May 1855, near London, the elder son of John Haddon, the head of John Haddon & Co, a firm of printers and typefounders established in 1814. He attended lectures at King's College London and taught zoology and geology at a girls' school in Dover, before entering Christ's College, Cambridge in 1875.[6] At Cambridge, he studied zoology and became the friend of John Holland Rose (afterwards Harmsworth Professor of Naval History), whose sister he married in 1881. Shortly after achieving his Master of Arts degree, he was appointed as Demonstrator in Zoology at Cambridge in 1879. For a time he studied marine biology in Naples.[7] CareerDublinIn 1880, he was appointed Professor of Zoology at the College of Science in Dublin. While there he founded the Dublin Field Club in 1885.[8] His first publications were an Introduction to the Study of Embryology in 1887, and various papers on marine biology, which led to his expedition to the Torres Strait Islands to study coral reefs and marine zoology, and while thus engaged he first became attracted to anthropology.[9] Torres Strait ExpeditionOn his return home, he published many papers dealing with the indigenous people, urging the importance of securing all possible information about these and kindred peoples before they were overwhelmed by civilisation. He advocated this in Cambridge, encouraged thereto by Thomas Henry Huxley, where he came to give lectures at the Anatomy School from 1894 to 1898.[1] Eventually, funds were raised to equip an expedition to the Torres Straits Islands to make a scientific study of the people, and Haddon was asked to assume the leadership.[7] To assist him he succeeded in obtaining the help of Dr W.H.R. Rivers, and in later years he used to say that he counted it his chief claim to fame that he had diverted Dr. Rivers from psychology to anthropology.[10] In April 1898, the expedition arrived at its field of work and spent over a year in the Torres Strait Islands, and Borneo, and brought home a large collection of ethnographical specimens, some of which are now in the British Museum, but the bulk of them form one of the glories of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge. The University of Cambridge later passed the wax cylinder recordings to the British Library. The main results of the expedition are published in The Reports of the Cambridge Expedition to Torres Straits.[7] Haddon was convinced that the art objects collected would otherwise have been destroyed by Christian missionaries determined to eradicate the religious traditions and ceremonies of the native islanders. He also filmed ceremonial dances. The findings were published in his 1901 book Head-hunters, Black, White and Brown.[11][12] Similar anthropological work, the recording of myths and legends from the Torres Strait Islands was coordinated by Margaret Lawrie during 1960–72. Her collection complements Haddon's work and can be found at the State Library of Queensland[13] In 1897, Haddon had obtained his Sc.D. degree in recognition of the work he had already done, some of which he had incorporated in his Decorative art of New Guinea, a large monograph published as one of the Cunningham Memoirs in 1894, and on his return home from his second expedition he was elected a fellow of his college (junior fellow in 1901, senior fellow in 1904).[1] He was appointed lecturer in ethnology in the University of Cambridge in 1900, and reader in 1909, a post from which he retired in 1926. He was appointed advisory curator to the Horniman Museum in London in 1901. Haddon paid a third visit to New Guinea in 1914 returned during the First World War.[1] Accompanied by his daughter Kathleen Haddon (1888–1961), a zoologist, photographer and scholar of string-figures,[14] the Haddons travelled along the Papuan coast from Daru to Aroma. While less discussed then his earlier work in the Torres Straits, this trip was influential in helping shape Haddon's later work on the distribution of material culture across New Guinea.[15][16] The war effort had largely destroyed the study of anthropology at the university, however, and Haddon went to France to work for the Y.M.C.A. After the war, he renewed his constant struggle to establish a sound School of Anthropology in Cambridge.[7] RetirementOn his retirement Haddon was made honorary keeper of the rich collections from New Guinea which the Cambridge Museum possesses, and also wrote up the remaining parts of the Torres Straits Reports, which his busy teaching and administrative life had forced him to set aside. His help and counsel to younger men was then still more freely at their service, and as always he continually laid aside his own work to help them with theirs.[7] Haddon was president of Section H (Anthropology) in the British Association meetings of 1902 and 1905. He was president of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, of the Folk Lore Society, and of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society;[1] received from the R.A.I. the Huxley Medal in 1920; and was the first recipient of the Rivers Medal in 1924. He was the first to recognise the ethnological importance of string figures and tricks, known in England as "cats' cradles," but found all over the world as a pastime among native peoples. He and Rivers invented a nomenclature and method of describing the process of making the different figures, and one of his daughters, Kathleen Rishbeth, became an expert authority on the subject.[7] His main publications, besides those already mentioned, were: Evolution in Art (1895), The Study of Man (1898), Head-hunters, Black, White and Brown (1901), The Races of Man (1909; second, entirely rewritten, ed. 1924), and The Wanderings of People (1911). He contributed to the Encyclopædia Britannica, Dictionary of National Biography, and several articles to Hastings's Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. A bibliography of his writings and papers runs to over 200 entries, even without his book reviews.[7] Though subsequently sidelined by Bronisław Malinowski, and the new paradigm of functionalism within anthropology, Haddon was profoundly influential mentoring and supporting various anthropologists conducted then nascent fieldwork: A.R. Brown in the Andaman Islands (1906–08), Gunnar Landtman on Kiwai in now Papua New Guinea (1910–12),[17] Diamond Jenness (1911–12), R.R. Marrett's student at the University of Oxford,[18] as well as John Layard on Malakula, Vanuatu (1914–15),[19] and to have Bronisław Malinowski stationed in Mailu and later the Trobriand Islands during World War 1.[20] Haddon actively gave advice to missionaries, government officers, traders and anthropologists; collecting in return information about New Guinea and elsewhere.[21] Haddon's photographic archive and artefact collections can be found in the Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology in Cambridge University, while his papers are in the Cambridge University's Library's Special Collections.[22] FamilyHaddon's wife, Fanny Elizabeth Haddon (née Rose), died in 1937, leaving a son and two daughters.[7] Haddon's daughter Kathleen was a zoologist, photographer, and scholar of string-figures. She accompanied her father on a journey along the coast of New Guinea during his Torres Straits Expedition. She married O. H. T. Rishbeth in 1917.[23] Reports of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to the Torres Straits

See also

References

Bibliography

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||