|

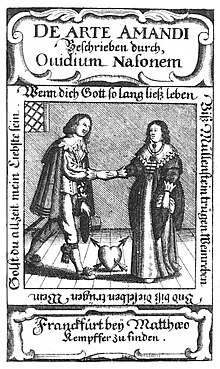

Ars Amatoria

The Ars amatoria (The Art of Love) is an instructional elegy series in three books by the ancient Roman poet Ovid. It was written in 2 AD. ContentBook one of Ars amatoria was written to show a man how to find a woman. In book two, Ovid shows how to keep her. These two books contain sections which cover such topics as 'not forgetting her birthday', 'letting her miss you - but not for long' and 'not asking about her age'. The third book, written two years after the first books were published, gives women advice on how to win and keep the love of a man ("I have just armed the Greeks against the Amazons; now, Penthesilea, it remains for me to arm thee against the Greeks..."). Sample themes of this book include: 'making up, but in private', 'being wary of false lovers' and 'trying young and older lovers'. The standard situations of finding love are presented in an entertaining way. Ovid includes details from Greek mythology, everyday Roman life and general human experience. The Ars amatoria is composed in elegiac couplets, rather than the dactylic hexameters, which are more usually associated with the didactic poem. ReceptionThe work was such a popular success that the poet wrote a sequel, Remedia Amoris (Remedies for Love). At an early recitatio, however, S. Vivianus Rhesus, Roman governor of Thracia, is noted as having walked out in disgust.[1] The assumption that the 'licentiousness' of the Ars amatoria was responsible in part for Ovid's relegation (banishment) by Augustus in 8 AD is dubious, and seems rather to reflect modern sensibilities than historical fact. For one thing, the work had been in circulation for eight years by the time of the relegation, and it postdates the Julian Marriage Laws by eighteen years. Secondly, it is hardly likely that Augustus, after forty years unchallenged in the purple, felt the poetry of Ovid to be a serious threat or even embarrassment to his social policies. Thirdly, Ovid's own statement[2] from his Black Sea exile that his relegation was because of 'carmen et error' ('a song and a mistake') is, for many reasons, hardly admissible. It is more probable that Ovid was somehow caught up in factional politics connected with the succession: Agrippa Postumus, Augustus' adopted son, and Augustus' granddaughter, Vipsania Julilla, were both relegated at around the same time. This would also explain why Ovid was not reprieved when Augustus was succeeded by Agrippa's rival Tiberius. It is likely, then, that the Ars amatoria was used as an excuse for the relegation.[3] This would be neither the first nor the last time a 'crackdown on immorality' disguised an uncomfortable political secret. LegacyThe Ars amatoria created considerable interest at the time of its publication. On a lesser scale, Martial's epigrams take a similar context of advising readers on love. Modern literature has been continually influenced by the Ars amatoria, which has presented additional information on the relationship between Ovid's poem and more current writings.[4] Pioneering feminist historian Emily James Putnam wrote that Medieval Europe, deaf to the humor that Ovid intended, took seriously the mock-analytical framework of Ars amatoria as a cue for further academic exegesis:

The Ars amatoria was included in the syllabuses of mediaeval schools from the second half of the 11th century, and its influence on 12th and 13th centuries' European literature was so great that the German mediaevalist and palaeographer Ludwig Traube dubbed the entire age 'aetas Ovidiana' ('the Ovidian epoch').[6] As in the years immediately following its publication, the Ars amatoria has historically been victim of moral outcry. All of Ovid's works were burned by Savonarola in Florence, Italy in 1497; an English translation of the Ars amatoria was seized by U.S. Customs in 1930.[7] Despite the actions against the work, it continues to be studied in college courses on Latin literature.[8] It is possible that Edmond Rostand's fictionalized portrayal of Cyrano de Bergerac makes an allusion to the Ars amatoria: the theme of the erotic and seductive power of poetry is highly suggestive of Ovid's poem, and Bergerac's nose, a distinguishing feature invented by Rostand, calls to mind Ovid's cognomen, Naso (from nasus, 'large-nosed'). See alsoReferences

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Ars Amatoria. Wikisource has original text related to this article:

|

||||||||||||||