|

Artistic freedomArtistic freedom (or freedom of artistic expression) can be defined as "the freedom to imagine, create and distribute diverse cultural expressions free of governmental censorship, political interference or the pressures of non-state actors."[1] Generally, artistic freedom describes the extent of independence artists obtain to create art freely. Moreover, artistic freedom concerns "the rights of citizens to access artistic expressions and take part in cultural life—and thus [represents] one of the key issues for democracy."[2] The extent of freedom indispensable to create art freely differs regarding the existence or nonexistence of national instruments established to protect, to promote, to control or to censor artists and their creative expressions. This is why universal, regional and national legal provisions have been installed to guarantee the right to freedom of expression in general and of artistic expression in particular. In 2013, Ms Farida Shaheed, United Nations special rapporteur to the Human Rights Council, presented her "Report in the field of cultural rights: The right to freedom of expression and creativity"[3] providing a comprehensive study of the status quo of, and specifically the limitations and challenges to, artistic freedom worldwide. In this study, artistic freedom "was put forward as a basic human right that went beyond the 'right to create' or the 'right to participate in cultural life'."[1] It stresses the range of fundamental freedoms indispensable for artistic expression and creativity, e.g. the freedoms of movement and association.[1] "The State of Artistic Freedom"[4] is an integral report published by arts censorship monitor Freemuse on an annual basis. Definition of artistic freedom Repeatedly, the terms artistic freedom and freedom of artistic expressions are used as synonyms. Their underlying concepts "art", "freedom" and "expression" comprise very vast fields of discussion: "Art is a very 'subtle'—sometimes also symbolic—form of expression, suffering from definition problems more than any other form."[5] As a result, "[i]t is almost impossible to give a satisfying definition of the concept art. It is even more difficult to define the concepts artistic creativity and artistic expression."[6] UNESCO's 2005 Convention on the Diversity of Cultural Expressions defines cultural expressions as "those expressions that result from the creativity of individuals, groups and societies, and that have cultural content"[7] while the latter "refers to the symbolic meaning, artistic dimension and cultural values that originate from or express cultural identities."[7] In the context of the freedom of (artistic) expressions, "[t]he word expression in the first instance refers to verbalisation of thoughts."[6] Freedom of artistic expression "may mean that we have to tolerate some art that is offensive, insulting, outrageous, or just plain bad. But it is a small price to pay for the liberty and diversity that form the foundation of a free society."[6] Officially, UNESCO defines artistic freedom as "the freedom to imagine, create and distribute diverse cultural expressions free of governmental censorship, political interference or the pressures of non-state actors. It includes the right of all citizens to have access to these works and is essential for the wellbeing of societies."[1] UNESCO puts forth that "artistic freedom embodies a bundle of rights protected under international law."[1] These include:[8]

Legal frameworks to protect and promote artistic freedom Legal frameworks to protect and promote artistic freedom reflect the conviction that "[c]ulture constitutes one process of, and space for, democratic debate. The freedom of artistic expression forms its backbone. There is compelling evidence that participation in culture also promotes democratic participation as well as empowerment and well-being of our citizens."[9] Farida Shaheed wrote: "Artists may entertain people, but they also contribute to social debates, sometimes bringing counter-discourses and potential counterweights to existing power centres."[10] Moreover, she emphasized that "the vitality of artistic creativity is necessary for the development of vibrant cultures and the functioning of democratic societies. Artistic expressions and creations are an integral part of cultural life,which entails contesting meanings and revisiting culturally inherited ideas and concepts."[10] According to Freemuse, "[p]opulists and nationalists, who often portray human rights as a limitation on what they claim is the will of the majority, are on the rise globally. As this phenomenon rises, artists continue to play an important role in expressing alternative visions for society."[11] This is why "artists are sometimes responsible for radical criticism."[6] As a result, artistic expressions and artists are suffering censorship and violations worldwide.

Thù" shows that "[i]t is not only governments violating the right to artistic freedom. 2016 saw a worrying amount of actions by non-state actors, ranging from militant extremists to peaceful community groups, against art and artists. In some instances, authorities censored artists based on requests or the interference from civil society groups."[12] Based on this development, "[m]ajor sources of international law across the board recognize freedom of artistic creativity explicitly, or implicitly, as an inherent element of the right to freedom of expression. In these instruments, the individual right to express ideas creatively is often irrevocably linked with the right to receive them."[13] The growing importance of artistic freedom as a specific right is reflected by the introduction of the role of the UN Special Rapporteur in the field of culture in 2009, and other rapporteurs, notably the Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression. UN instrumentsArtistic freedom as a specific rightAccording to Farida Shaheed, the most explicit legal provisions protecting the right to the freedom indispensable for artistic expression and creativity are the following:[10]

In September 2015, 57 UN Member States reaffirmed the right to freedom of expression including creative and artistic expression through a joint statement.[16] Additionally, in 2015, the Carthage Declaration on the Protection of Artists in Vulnerable Situations was adopted in Tunis.[17][18] Artistic freedom as a pillar of the right to freedom of expressionThe following legal instruments do not specifically mention artistic freedom but rather understand it as a pillar of freedom of expression in general related to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. They aim to guarantee the right to freedom of expression or the right to participate in cultural life without specific reference to the arts.[10][13]

UNESCO instruments1980 UNESCO Recommendation Concerning the Status of the ArtistArtistic freedom first appeared as a distinct right in UNESCO's 1980 Recommendation concerning the Status of the Artist underlining "the essential role of art in the life and development of the individual and of society' and the duty of States to protect and defend artistic freedom."[19] Although not a binding instrument, the Recommendation is an important reference in defining artists' rights across the spectrum worldwide. The 1980 Recommendation serves as a reference for policy development and as a basis for new formulations of cultural policies:

2005 UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural ExpressionsThe 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions acknowledges that "the diversity of cultural expressions can only be promoted if human rights and fundamental freedoms are guaranteed."[20] A guiding principle of the 2005 Convention is that "cultural diversity can be protected and promoted only if human rights and fundamental freedoms, such as freedom of expression, information and communication, as well as the ability of individuals to choose cultural expressions, are guaranteed."[1] In this context, governance of culture refers to policies and measures governments establish to promote and to protect all forms of creativity and artistic expressions. The most recent UNESCO Convention in the field of culture and ratified by 146 Parties, it frames the formulation and implementation of different types of legislative, regulatory, institutional and financial interventions to promote the emergence of diverse cultural and creative industry sectors around the world. As a result, it aims to ensure participation in cultural life and to support access to diverse cultural expressions (film, music, performing arts, etc.).[1] National legislative measures to promote artistic freedomSimilar to the aforementioned universal instruments to protect artists and artistic freedom, "[i]n national constitutions (...), freedom of artistic creativity is often located within the strongly-protected right to freedom of expression."[13] Certain countries also "recognize the freedom of artistic expression within the ambit of the right to science and culture."[13] The following national legislative measures are listed in alphabetical order. The list is to be completed. Burkina FasoAdopted on 23 May 2013 by "Direction générale des arts (DGA)", the decree "Décret portant statut de l'artiste au Burkina Faso" envisages improving the social protection and the living conditions of artists, particularly the social security of employed artists and freelancers, the return of social contributions of artists and the complement dispositive for mutual accountability.[21] CanadaIn Canada, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms protects artistic expression.[22][23] FranceIn July 2016, France amended its legislation in order to extend it with the legal protection of artistic freedom, architecture and heritage. For the first time in international law, artistic expressions are established as public goods and the "dissemination of artistic creation is free". This implies not only that artists are free to create but also that the wider public has access to it.[8] As a result, art and artistic expressions cannot be censored or simply excluded from exhibits and other events. GermanyArticle 5 of the German Basic Law contains a special paragraph that connects the right to freedom of expression with the right to freely develop the arts and sciences."[13] IndonesiaOn 12 January 2012, Indonesia ratification UNESCO 2005 Convention.[24] When 2017, Indonesia published Cultural Advancement Law based on principles 11 values, including guaranteeing freedom of expression, ensuring the protection of cultural expression, providing cultural facilities and infrastructure, also funding sources for cultural advancement. MexicoOn 19 June 2017, Mexico published its "Ley General de Cultura y Derechos Culturales"[25] promising strong protection for artistic freedom and artists and cultural professionals, a provision specifically needed given the alarming conditions under which Mexican artists, journalists and cultural professionals currently work.[4] SpainOn 6 September 2018, the Spanish Congress of Deputies unanimously ratified a proposal assigned to elaborate a "Estatuto del Artista y del Profesional de la Cultura". Broadly, the decree aims to protect and promote artists with regard to taxation, their work security and legal protection.[26][27] SwedenArticle 1 (2) of the Swedish Fundamental Law explicitly includes the freedom of artistic creation as part of the key purposes of freedom of expression: "The purpose of freedom of expression under this Fundamental Law is to secure the free exchange of opinion, free and comprehensive information, and freedom of artistic creation."[13][28] TogoOn 20 June 2016, Togo adopted its "Statut de l'artiste". Its major objective is to acknowledge artists as individuals and their moral role in society, their contributions towards the intellectual sphere protected by copyright. It defines the rights and duties linked to artistic professions and aims to promote creativity and to protect artists socially.[29] TunisiaAdopted in 2014, article 42 of the Tunisian Constitution states: "The right to culture is guaranteed. The freedom of creative expression is guaranteed. The State encourages cultural creativity and supports the strengthening of national culture, its diversity and renewal, in promoting the values of tolerance, rejection of violence, openness to different cultures and dialogue between civilizations."[30] United StatesIn the U.S., the first amendment protects artistic expression.[31][13] According to the Court, freedom of artistic creativity is an element of the respect for freedom of self-expression, one of the core values of the First Amendment.[13] However, the U.S. Supreme Court has never considered artistic freedom as a distinct category akin to political or commercial speech: "it rather addresses the various forms of art in their relation to the First Amendment on a contextual basis."[13] Challenges to artistic freedomThe International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) explains the purpose of its existence with the following statement:

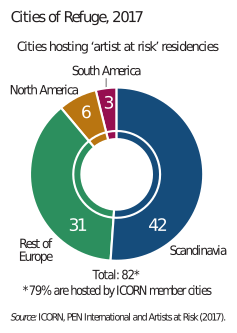

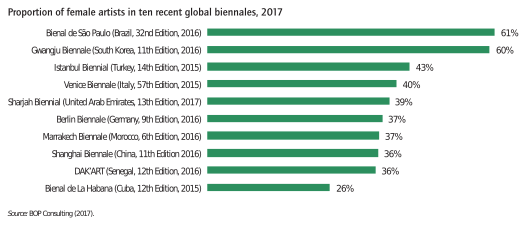

Freemuse's report (2018) demonstrates that artistic freedom "is being shut down in every corner of the globe, including in the traditionally democratic West. According to Freemuse's 2016 report, the music industry is the main target of serious violations, and second to film in overall violations, including non-violent censorship.[33] The most serious violations included the murder of Pakistani Qawwali singer Amjad Sabri and the killing of Burundi musician Pascal Treasury Nshimirimana.[12] In 2019, Karima Bennoune, UN Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, underlines that "the freedom of artistic expression and creativity of persons with disabilities, women or older persons"[17] remains significantly restricted. She states that "many cultural rights actors have not incorporated a gender perspective into their work, while many women's rights advocates have not considered cultural rights issues."[17] Referring to Freemuse's 2016 report, UNESCO stresses that "laws dealing with terrorism and state security, defamation, religion and 'traditional values' have been used to curb artistic and other forms of free expression."[1]  Moreover, new digital technologies, including social media platforms, are challenging artistic freedom: "Art in the online and digital space continues to challenge authorities and corporations who are quick to react by closing down expression rather than using it as an opportunity to foster it."[4] Social media and music streaming channels, like Instagram and SoundCloud are becoming the platforms on which artists publicly display and promote their work. However, they also bring with them threats to rights and freedoms. Online trolls often intimidate artists to withdraw their work.[1][4] Additionally, growing digital surveillance has a corrosive effect on artistic freedom.[1] Many platforms have established mechanisms, such as Instagram's guidelines on 'standards of behavior' whose formulations are very vague. This provides disproportionate power to individuals and organizations who use the platform's reporting processes to get individual artworks removed, and sometimes entire accounts blocked. In addition, the impact of algorithms on diversity of content is another area of concern: platforms display a plethora of cultural offerings, but also control not only sales but also communication and the recommendation algorithms (e.g. adapting offered content to the profile of each internet user). These algorithms finally serve to promote certain contents while oppressing others.[4] In conclusion, new digital technologies—while providing a platform for the distribution of artistic content—may interrupt the flow of ideas of artists and curtail their artistic freedom. In the 10th Anniversary UN Report on Cultural Rights, Ole Reitov, former executive director of Freemuse, underscores the progressive fact that "artistic freedom is no longer a 'marginalized' issue in the 'world of freedom of expression'".[17] Since Farida Shaheed's report and inspired by lobbying from arts and human rights NGOs, efforts to promote artistic freedom have multiplied across the entire United Nations system: "The UN Universal Periodic Review provides an opportunity for NGOs, among others, to make submissions on States' failures to meet human rights standards, including artistic freedom. New calls for a UN Action Plan on the Safety of Artists and Audiences (similar to the one for journalists) have been put forward."[1] As UNESCO's Global Report "Re|shaping Cultural Policies" (2018) shows, the number and capacity of organizations monitoring artistic freedom is increasing. "In this domain as well, cities are taking valuable initiatives by providing safe havens for artists at risk."[1][17] As the list above shows, "measures to support the economic and social rights of artists are appearing increasingly in national legislation, especially in Africa."[1] Monitoring artistic freedomDespite the progress made and legal instruments established to promote and protect freedom of artistic expressions, "there is urgent need for monitoring and surveillance, essential if these freedoms are to become a permanent reality."[34]  Karima Bennoune notes that the increasing number of reported attacks perpetrated by State and non-State actors against cultural professionals reflects the boosting capacity of monitoring artistic freedom.[17] She states the UNESCO global reports monitoring the implementation of the 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of Cultural Expressions have been "[o]f particular relevance".[17] The reports provide a monitoring framework comprising four overarching goals to enhance cultural policies worldwide.[35] One of these goals aims to "Promote Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms" and encompasses artistic freedom as an "area of monitoring" incorporating core indicators to measure achievements regarding the rights and protection of artists.[17] Additionally, the framework relates artistic freedom to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16 of the UN 2030 Agenda, which aims to "'Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels".[36] Specifically, the SDG's target 16.10 aims to "ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements".[8][36]  Additionally, there are many other initiatives advocating and monitoring artistic freedom. Alongside other organizations documenting violations against freedom of artistic expression (such as Arterial Network, Artists at Risk Connection, PEN International and the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions), Freemuse is an independent international organization particularly monitoring the freedom of expression of musicians and composers worldwide. "Freemuse's reports collated from all over the world show that artists are increasingly facing censorship, persecution, incarceration or death, because of their work."[37] There is also monitoring carried out by Koalisi Seni, an institution that advocates for arts policy in Indonesia. From the results of its monitoring, Koalisi Seni notes, in Indonesia during the pandemic, social restrictions to reduce the spread of COVID-19 became a new excuse for the state to suppress arts activities.[38] There are also notes that stigmatization of art often occurs because art is considered to damage people's morals and invite immorality.[39] In order to monitor the actions taken to implement the 1980 Recommendation concerning the Status of the Artists, the Secretariat of the 2005 UNESCO Convention (see below) runs a global survey every four years gathering information from Members States, NGOs and INGOs and prepares a report, which is then submitted to the General Conference.[19] See alsoReferences

External links

|