|

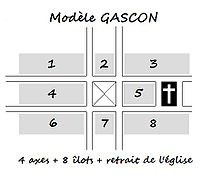

Bastide Bastides are fortified[1] new towns built in medieval Languedoc, Gascony, Aquitaine, England and Wales[2][3] during the 13th and 14th centuries, although some authorities count Mont-de-Marsan and Montauban, which was founded in 1144,[4] as the first bastides.[5] Some of the first bastides were built under Raymond VII of Toulouse to replace villages destroyed in the Albigensian Crusade. He encouraged the construction of others to colonize the wilderness, especially of southwest France. Almost 700 bastides were built between 1222 (Cordes-sur-Ciel, Tarn) and 1372 (La Bastide d'Anjou, Tarn).[6] HistoryBastides were developed in number under the terms of the Treaty of Paris (1229), which permitted Raymond VII of Toulouse to build new towns in his shattered domains but not to fortify them. When the Capetian Alphonse of Poitiers inherited, under a marriage stipulated by the treaty, this "bastide founder of unparalleled energy" consolidated his regional control in part through the founding of bastides.[7] Landowners supported development of bastides to generate revenues from taxes on trade rather than tithes (taxes on production). Farmers who elected to move their families to bastides were no longer vassals of the local lord and became free men and the development of bastides contributed to the waning of feudalism. The new inhabitants were encouraged to cultivate the land around the bastide, which, in turn, attracted trade in the form of merchants and markets. The lord taxed dwellings in the bastides and all trade in the market. The legal footing on which the bastides were set was that of paréage with the local ruling power, based on a formal written contractual agreement between the landholder and a count of Toulouse, a king of France, or a king of England. The landholder might be a cartel of local lords or the abbot of a local monastery. Responsibilities and benefits were carefully framed in a charter, which delineated the franchises ('liberties') and coutumes ('customs') of the bastide. Feudal rights were invested in the sovereign, with the local lord retaining some duties as enforcer of local justice and intermediary between the new inhabitants— required to build houses within a specified time, often a year, and the representatives of the sovereign.[8] Residents were granted a houselot, a kitchen garden lot (casale), and a cultivable lot (arpent) on the periphery of the bastide's lands. The bastide hall and the church were often first constructed of wood. After the bastide was established, they were replaced by structures of stone. Structural elementsScholarly debate has taken place over the definition of a bastide. They are now generally described as any town planned and built as a unit, by one founder.[5] Most bastides were developed with a grid layout of intersecting streets, with wide thoroughfares that divide the town plan into insulae, or blocks, through which a narrow lane often runs.[9] They included a central market square surrounded by arcades (couverts) through which the axes of thoroughfares passed, with a covered weighing and measuring area. The market square often provided the module into which the bastide is subdivided.[10] The Roman model, the castrum with its grid plan and central forum, was inescapable in a region since Roman planning precedents survived in medieval cities such as Béziers, Narbonne, Toulouse, Orange and Arles. The region of the bastides had been one of the last outposts of Late Antiquity in the West.[11] Central square The main feature of all bastides is a central, open place, or square. It was used for markets, but also used for political and social gatherings. A typical square, (which was probably a model for other bastides), can be found in Montauban. Generally, there is just one square. Saint-Lys and Albias are different because they have two squares, one for the market and one square for the church. The square is also used to divide the city into quarters. Generally, it lies outside the main street (the axis) which carried the traffic. There are three possible layouts: Completely closed: The square does not touch any street. These are very rare; there is one example at Tournay with a size of 70 metres (230 ft) by 72 m (236 ft)). Single-axis: The single-axis design of the bastide makes all roads run in one direction and are parallel. Here and there, there are alleys cut between the roads. The square is placed between two roads. These squares are usually 50 m (164 ft) to 55 m (180 ft) on each side. Grid-layout; usually based on the square in Montauban. Generally the flattest place in the bastide was used for the square. ChurchThe church was almost never on the central square but usually at an angle, facing the square diagonally. One of the rare exceptions is Villefranche-de-Rouergue but this one was built two centuries after the square. Houses There were clear rules how houses could be built inside the bastide. The front of the houses, the façades, had to line up. Also, there had to be a small space between the houses. The different housing lots were all alike, 8 m (26 ft) by 24 m (79 ft) being a common size. There were only a limited number of lots. This varied between ten and several thousand (3,000 in Grenade-sur-Garonne) StreetsThe streets were usually 6–10 m (20–33 ft) wide, so a chariot could pass through. They ran alongside the façades of the houses. Alleys run between streets, these are usually only 5–6 m (16–20 ft) wide. Sometimes, they are only 2–2.5 m (6 ft 7 in – 8 ft 2 in) wide. In a bastide there were usually between one and eight streets. City walls When bastides were founded, most had no city walls or fortifications because it was a peaceful time in history, and walls were prohibited by the Treaty of Paris (1229). Fortifications were added later and were paid for through a special tax or carried out through a law that required the people of the city to help build the walls. A good example is Libourne. Ten years after the city was founded, the people asked for money to build city walls. Once they had received the money, they spent it on making their city prettier, rather than building walls.[citation needed] At the beginning of the Hundred Years' War, many bastides that had no city walls were destroyed. Some of the others quickly built stone walls to protect the city. Structure and location Ease of tax collection was another reason for the grid layout, as the village was taxable module by module, and the organized central area. The bastides' forms resulted from "the friction engendered by interaction, expedience, pragmatism, legal compromise, and profit," Adrian Randolph observed in 1995.[12] More rarely, such planned cities were developed according to a circular plan.[13] Some bastides were not so geometrically planned: "The block geometry of the bastides was not a rigid framework into which a town was squeezed; it resembles more closely a net, thrown upon the site and adapting to its nuances," Randolph remarks.[14] Most bastides were built in the Lot-et-Garonne, Dordogne, Gers and Haute-Garonne départements of France, because of the altitude and quality of the soil. Some were constructed in important defensive positions. The best-known today are probably Andorra la Vella and Carcassonne, but the most populated is Villeneuve-sur-Lot, the 'new town on the River Lot'. See also

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

|