|

Battle of Stillman's Run

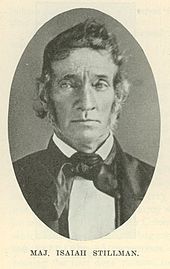

The Battle of Stillman's Run, also known as the Battle of Sycamore Creek or the Battle of Old Man's Creek, occurred in Illinois on May 14, 1832. The battle was named for the panicked retreat by Major Isaiah Stillman and his detachment of 275 Illinois militia after being attacked by an unknown number of Sauk warriors of Black Hawk's British Band. The numbers of warriors has been estimated at as few as fifty but as many as two hundred participated in the attack. However, reports found in Whitney's Black Hawk War (Letters and reports compiled by the Illinois State Library) indicated that large numbers of Indians were on the move throughout the region, and it appeared that widespread frontier warfare was underway. The engagement was the first battle of the Black Hawk War (1832), which developed after Black Hawk crossed the Mississippi River from Iowa into Illinois with his band of Sauk and Fox warriors along with women, children, and elders to try to resettle in Illinois. The militia had pursued a small group of Sauk scouts to the main British Band camp following a failed attempt by Black Hawk's emissaries to negotiate a truce. During the engagement, 12 militiamen were killed by Band warriors while making a stand on a small hill. The remainder of the militia fled back to Dixon's Ferry. Citizens erected a monument in 1901 in Stillman Valley, Illinois commemorating the battle. A 2006 article corroborates that militia volunteer Abraham Lincoln was present at the battleground's burials; sources agree about little else. Investigation continues in the early 21st century about facts of the skirmish. BackgroundBlack Hawk, a Sauk chief, believed that the Treaty of St. Louis (1804) was invalid. It ceded Sauk territory to the US that included his birthplace. He led a number of incursions across the Mississippi River from Iowa to Illinois beginning in 1830. Each time, he was persuaded to return west without bloodshed. In April 1832, encouraged by promises of alliances with other tribes and the British authorities in British North America, he again moved his "British Band" into Illinois.[1] Finding no allies, he attempted to return to Iowa, but ensuing events led to the Battle of Stillman's Run.[2] A number of other engagements followed, and the state militias of Wisconsin and Illinois were mobilized to hunt down Black Hawk's band. The conflict became known as the Black Hawk War.

On April 5, 1832, Black Hawk and around 1,000 warriors and civilians recrossed the Mississippi River into Illinois. About half of Black Hawk's band were combatants and the rest were a combination of women, children, and elderly. The band consisted of Sauk, Fox, some Potawatomi, and some Kickapoo; in addition some members of the Ho-Chunk nation were sympathetic to Black Hawk.[3][4][5] Black Hawk's reason for crossing into Illinois is disputed. It has long been believed that he wanted to reclaim lost territory and, perhaps, create a confederacy of Native Americans to stand against white settlement.[5][6] However, modern historians have questioned this and indicated that Black Hawk may have been trying to resettle among the Ho-Chunk and point to the large number of non-combatants that accompanied Black Hawk's supposed war party. Other Illinois tribes promised aid to the British Band and Black Hawk believed that he had been promised assistance by the British in Canada.[5] Black Hawk led the march of the group along the Rock River into Illinois. Illinois Governor John Reynolds perceived the return of Black Hawk as an invasion, and he immediately called up the militia.[7] General Henry Atkinson, whom Black Hawk addressed as "White Beaver," commanded the military expedition.[8][9] PreludeAtkinson was not told about Governor Reynolds' decision to order Major Isaiah Stillman's militia to march on Old Man's Creek, despite being in overall command. Reynolds' orders, issued on his behalf by General Samuel Whiteside to Stillman, were for Stillman to find Black Hawk and coerce him into submission. Following these orders, Stillman moved on Old Mans Creek.[10][11] Whiteside had refused to accept Stillman's battalion under his command, thus leaving it "orphaned" and under the direct command of Governor Reynolds.[12] The militia commanded by Whiteside grew restless as they awaited the arrival of Atkinson and his Army regulars; many of the volunteer militia wanted to quit the war and head back home.[12] When diplomacy failed to persuade Black Hawk to take his band back west to Iowa, Stillman and Bailey's battalions of Illinois Militia were marched up the Rock River.[13] Prior to the battle at Stillman's Run, Black Hawk's grand vision of British support and a Native American confederacy had collapsed.[4] No significant parties aided him and his followers. The British Band started to weaken with hunger, and Black Hawk soon realized that the only option was to return across the Mississippi River. When he detected the U.S. militia camp eight miles (13 km) away, Black Hawk sent out peace envoys in order to negotiate a truce. They were told to wave a white flag at the militia.[14] Battle On May 14, 1832, a detachment of 275 militia under the command of Majors Isaiah Stillman and David Bailey, under orders from Illinois Governor Reynolds, were encamped near Old Man's Creek, not far from its confluence with the Rock River.[11][15] The militia camp was located about three miles (5 km) east of the Rock River near present-day Stillman Valley, Illinois, and seven miles (11 km) south of the Sauk encampment.[11] It is believed that the militia and its commanders were unaware of their proximity to Black Hawk's British Band.[11] In conference with the local Potawatomi, Black Hawk learned of Stillman's presence and sent three emissaries to the militia camp under a flag of parley in order to negotiate a peace with the soldiers.[7] The already suspicious soldiers took the three emissaries to their camp, and during the proceedings the militia became aware of several of Black Hawk's scouts in the surrounding hills, watching the proceedings.[7] Once the scouts were spotted, soldiers shot at the three emissaries, killing one. The other two fled back toward their camp, located near the confluence of the Rock and Kishwaukee rivers.[14] The scouts were pursued by the disorganized militia and several were killed. The surviving scouts arrived at Black Hawk's camp ahead of the militia and reported the events. At the camp, the warriors set up a skirmish line in order to fend off the pending militia attack.[7] The militia soldiers, intent on pursuing the scouts, chased them back toward the main force of Black Hawk's warriors and their skirmish line.[7] Black Hawk and his force concealed themselves and ambushed the pursuers.[2] Believing that thousands of Sauk and Fox were attacking them, the militia panicked and fled back to the main force camped at Dixon's Ferry.[16] Stillman's exact whereabouts are unknown during this point in the battle. His later account published in a newspaper did not mention his location and noted his only order was to retreat. Stillman's account, published in the Missouri Republican, has been called fanciful.[11] Twelve of Stillman's militia were killed in the melee.[17] A band of volunteers under the leadership of Captain John Giles Adams made a stand on a hill south of the main militia camp. The men fought by moonlight as the main body of the militia fled back to Dixon. The entire 12-man detachment, including Adams, was killed in the fight.[15] Dyer has said that Adams may have been killed by his own men as he attempted to muster them to battle.[11] The number of Sauk and Fox killed in the engagement is largely unknown; the militia party that was sent to locate the "missing" 53 militia men found no dead Sauk.[11] Black Hawk is quoted as saying at least three and maybe as many as five of his warriors were killed.[18] Lincoln's role The facts about Abraham Lincoln's service during the Black Hawk War have been disputed. Lincoln was associated with two major battle sites, including Stillman's Run, in the aftermath of combat. A number of sources assert that on June 26, 1832, the morning after the Second Battle of Kellogg's Grove, members of the company of Captain Jacob M. Early arrived at the grove to help bury the dead. One of these soldiers was Lincoln, who assisted with the burial. His later statement about the events has been linked to both the battle at Kellogg's Grove and the fight at Stillman's Run.[19][20][21]

The Lincoln quote was featured in both William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Wiek's Life of Lincoln and Carl Sandburg's Lincoln biography, Abraham Lincoln The Prairie Years.[19] Lincoln's presence at Stillman's Run has been under investigation in the early 21st century, but his presence at Kellogg's Grove has been corroborated by several sources.[19][21][22] In a 2006 article, author Scott Dyer asserted that Whiteside's men, including Captain Lincoln, "paraded" the area the morning after, and buried the dead from Stillman's Run. Their movements were an unsuccessful effort to draw out the Sauk, after which they returned to Dixon's Ferry.[11]  During an 1848 speech before the U.S. Congress in which he referred to his Black Hawk War service, Lincoln noted Stillman's Run by name:

The marble facade on the Stillman Valley monument, erected in 1901 to commemorate the battle, refers to Lincoln's presence at Stillman's Run, "The presence of soldier, statesman, martyr, Abraham Lincoln assisting in the burial of these honored dead has made this spot more sacred."[20] Other sources assert that General Whiteside originally buried the dead in a common grave on a ridge south of the battlefield, marked with a rudimentary wooden memorial. These sources make no mention of Lincoln.[24][25] Aftermath Following the first confrontation with Black Hawk at Stillman Valley, the press reported that 2,000 "bloodthirsty warriors were sweeping all Northern Illinois with the bosom of destruction," sending shock waves of terror through the region.[13] Past midnight on May 15, soldiers from Stillman's ill-fated detachment began streaming back into Dixon's Ferry, wide-eyed and panic-stricken, telling tales of a horrible slaughter that had ensued during the battle. In the immediate aftermath of the battle, 53 militia men were missing. Later officials determined that the majority of these men had simply bypassed Dixon's Ferry on their way home.[11]  After this initial skirmish, Black Hawk led many of the civilians in his band to the Michigan Territory.[13] On May 19, the militia traveled up the Rock River trailing and searching for Black Hawk and his band.[13] Several small skirmishes and massacres ensued over the next month in northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin before the militia regained public confidence in battles at Bloody Lake and Waddams Grove.[26] Critics of the Illinois Militia, mostly members of the Regular Army, attacked their behavior at the debacle at Stillman' Run. They began to refer to the battle at Old Man's Creek as the Battle of Stillman's Run, because Stillman had apparently fled with the panicked militia.[11] Armed hostilities during the Black Hawk War began at Stillman's Run, and the victory was unexpected for Black Hawk and his British Band.[2] Black Hawk feared that the white militia and its allies would seek revenge through his total defeat.[27] Leading his starving band, Black Hawk fled from Atkinson's pursuing army. The chase would take them as far as present day Madison, Wisconsin. It ended at the Battle of Bad Axe, where the militia and its allies massacred a weakened foe, by then made up of mostly women and children.[28] The remains of the soldiers at Stillman's Run were originally buried in a common grave, but who buried them remains an open question.[20][22][24] A memorial, erected in 1901, stands near their marked graves.[20] The monument and battle site are listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. They are near Illinois Route 72 a block west of present-day Stillman Creek.[29][30][31] See alsoNotes

References42°6′24″N 89°10′33″W / 42.10667°N 89.17583°W

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||