|

Black Death in the Holy Roman Empire

The Black Death was present in the Holy Roman Empire between 1348 and 1351.[1] The Holy Roman Empire, composed of modern-day Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands, was, geographically, the largest country in Europe at the time, and the pandemic lasted several years due to the size of the Empire. Several witness accounts do exist from the Black Death in the Holy Roman Empire, although they were often either written after the events took place, or are very short.[1] BackgroundThe Holy Roman Empire in the mid-14th century At this point in time, the Holy Roman Empire was the geographically largest nation in Europe, though the population of France was bigger. It was a personal union under the King of Bohemia, who was also the Holy Roman Emperor.[2] The Black DeathSince the outbreak of the Black Death at the Crimea, it had reached Sicily by an Italian ship from the Crimea. After having spread across the Italian states, and from Italy to France, the plague reached the borders of the Empire from France in the West, and from Italy in the South.[3] Progress of the plagueThe bubonic plague pandemic known as the Black Death reached Switzerland and Austria from Northern Italy in the South and Savoy in the West, and the Rhine and Central Germany from Northern France, and Northern Germany from Denmark. It continued from the Empire East to the Baltics and finally to the Rus' principalities.[4] SwitzerlandThe Black Death reached Switzerland south from Ticino in Italy, and West to Rhone and Geneva from Avignon in France. According to tradition, Mühldorf am Inn was the first German language city to be affected by the Black Death, on 29 June 1348.[1] Most of Switzerland was affected during the year of 1349, when the plague reached Bern, Zürich, Basel and Saint Gallen.[5] AustriaThe Black Death in Austria is mainly described by the chronicle of the Neuberg Monastery in Steiermark. The Neuberg Chronicle dates the outbreak of plague in Austria to the feast of St Martin on 11 November 1348. In parallel with the plague, severe floods affected Austria. The plague interrupted the ongoing feud among the nobility, who were forced to cooperate against it. The Neuberg Chronicle describes an outbreak of festivities among the peasantry and public to distract themselves from the catastrophe, and how law and order collapsed.[1] The plague reached Vienna in May 1349, where it lasted until September and killed about one-third of the population.[6] GermanySouthern GermanyIn the summer of 1349, the plague spread from Basel in Switzerland North toward Strasbourg. The plague reached Strasbourg from Colmar 8 July.[7] During the summer and autumn of 1349, the plague spread West from Strasbourg toward Mainz, Kassel, Limburg, Kreuznach, Sponheim and finally (in December) to Cologne; and East toward Augsburg, Ulm, Essingen and Stuttgart.[1] Northern GermanyThe Black Death reached Northern Germany in the early summer of 1350 when it arrived in Magdeburg, Halberstadt, Lübeck and Hamburg. The plague appears to have reached the Northern port cities in different time periods, likely because it was spread by sea rather than land: the inland cities of Northern Germany, significantly, were affected at a later date in 1350 than the port cities along the North coast.[1] It finally reached Prussia and from there to the Baltics in 1351, and from there to the Rus' principalities.[8] Low Countries2 pages later, the Cronica mentions itinerant flagellants, and the burning of Jews, under the year 1349, without explicitly linking these events to the "great dying" reported in 1347.[9] The Black Death events in the present-day Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg are documented in a range of sources.[9] In the often brief descriptions that feature in sources that have survived, three common elements can be identified:

The Lower Rhine city of Cologne appears to have experienced an outbreak of Black Death as early as 1347, for which the local Cronica vander hiliger stat Coellen (1499) records: "In the said year [1347] and the two years after, there was a great dying throughout the world, both amongst the pagans and the Christians."[9] Two pages later, brief reports are given on the "Flagellant Brothers" (Geysellbroederen) or "Cross Bearers" (Cruysdreger), and the burning of the Jews,[c] without linking these three events (the same juxtaposition without connection happens in the Nuremberg Chronicle of Hartmann Schedel).[9] On the other hand, a chronicle on the Duchy of Guelders, written in Nijmegen around 1459, does link all three events:

In June 1349, abbot Gilles Li Muisis from Saint-Martin Abbey, Tournai reported large numbers of deaths, and mass graves being dug to bury the deceased.[9] Furthermore, he noted that people were accusing the Jews of allegedly having poisoned the water wells which had supposedly caused the epidemic; as a result, many Jews were persecuted and burnt at the stake, with massacres taking places in Brussels and Cologne.[9] Muisis wrote these events down without judgement as to whether he believed the accusations, nor how he thought about the way the authorities handled the persecutions, as if he did not know what to do with the situation.[9] On the other hand, Muisis showed great sympathy for the Christian piety displayed by the itinerant groups of flagellants.[9]  The last chapter of Book V of the Brabantsche Yeesten, a rhymed chronicle by Antwerp clerk Jan van Boendale (died c. 1351), was entitled On the Flagellants (Van den gheesselaren[10]).[9]

The story goes on to narrate that Jews were "also done pain here in Brabant", because they allegedly had used "venom" (fenine) "in many cities, in order to spoil Christendom, therefore the Jews had to die."[10] Duke John is then said to have all Jews arrested (va[ng]en, "caught"), whom were "burnt, beaten or drowned", ending that this all happened in the years 1349 and 1350.[10] The Boec vander wraken ("Book of Wraths"), written by an unknown Antwerp author (probably also Jan van Boendale) between 1346 and 1351, reports many details of the plague in the region, as well as flagellants, although it makes no specific mention of events in Antwerp itself.[9] "The disease began in Babel, I was assured, and soon spread across the Mediterranean in southern Italy, Calabria, Sicily, Cyprus, Tuscany, Lombardy, in Romagna, thence to France and from France to England," the Boec claims.[9] Entire villages are depopulated, and local governments and courts ceased to function.[9] In one anecdote from Utrecht, there was a mansion whose inhabitants and cattle had all died; two burglars stole some jewellery from the building, after which one of them died as well.[9] The author had a double explanation for the plague, believing it to be both a divine punishment, as well as a plot by the Jews to poison the drinking waters; therefore, he condoned the anti-Jewish pogroms.[9] The Rhymed Chronicle of Flanders (probably written around 1410 in Ghent), as preserved early-15th century Comburg Manuscript, noted that between 1348 and 1350, there was die groete steerfte ("the great dying"):[11]

– On the flagellant brothers (1530 [1497]).[d]

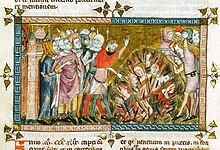

It is known that the plague went as far as Hainaut and Flanders in the summer of 1349, but its progress further North cannot be traced, and there is no documentation of it in Central Netherlands. It is however confirmed that the ongoing reclaim of wetlands in Holland discontinued at this point, possibly because the population was suddenly smaller and there was, therefore, enough land for everyone.[1] The very northern part of the Netherlands, Frisia, is documented to have been reached by the plague, where it came from Germany in 1350, and there is a description of it in Deventer and Zwolle.[1] In Zwolle, a dispute even occurred between religious authorities as to who had the right to perform mass burials.[13] BohemiaAccording to the traditional narrative, Bohemia was spared from the Black Death. This was also used as propaganda. Since the Black Death was commonly interpreted as a divine punishment for the Sins of humanity, the fact that Bohemia was spared was a great gain for the reputation of Bohemia, and the Bohemian elite and government made use of this. In the famous chronicle Cronica Boemorum regum by Francis of Prague (Franciscus Pragensis), the king and the Kingdom of Bohemia were portrayed as free from the sins God's had sent the plague to punish the rest of Europe for, and the air as pure and clear.[1] With the exception of local outbreaks in Brno and Znojmo in Moravia in December 1351, no contemporary sources contradict the contemporary claim that Bohemia was spared.[1] Archaeological research suggests that the Black Death might have been responsible for some of the mass burials at Sedlec Ossuary.[14] The reason why Bohemia was spared from the plague is debated. It has been suggested, that since Bohemia lacked water ways and could only be reached by land; and that most of the traffic came to Bohemia from Germany, where all traffic collapsed because of the Black Death there, the fact that the traffic from Germany was interrupted by the plague resulted in an unintentional quarantine, which spared Bohemia.[1] Consequences The Holy Roman Empire was the stage for both the Jewish pogroms as well as the flagellants during the Black Death.[1] As the plague progressed, the Jews were accused to have caused it by well poisoning. Rumours of well poisoning were spread in France, but they were directed more toward Jews within the borders of the Holy Roman Empire, where there was a larger Jewish population than in France.[1] The persecutions started to cause mass trials and mass executions of Jews in the Duchy of Savoy, and turned into massacres when the rumours of the trials in Savoy reached Switzerland and Germany.[1] According to the chronicler Heinrich von Diessenhoven, all Jews from Cologne to Austria were killed in a series of massacres between November 1348 and September 1349.[1] See alsoNotes

References

|