|

Black Moshannon State Park

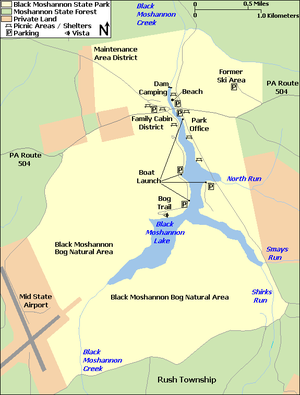

Black Moshannon State Park is a 3,480-acre (1,410 ha) Pennsylvania state park in Rush Township, Centre County, Pennsylvania, United States. It surrounds Black Moshannon Lake, formed by a dam on Black Moshannon Creek, which has given its name to the lake and park. The park is just west of the Allegheny Front, 9 miles (14 km) east of Philipsburg on Pennsylvania Route 504, and is largely surrounded by Moshannon State Forest. A bog in the park provides a habitat for diverse wildlife not common in other areas of the state, such as carnivorous plants, orchids, and species normally found farther north. As home to the "largest reconstituted bog in Pennsylvania", it was chosen by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources for its "25 Must-see Pennsylvania State Parks" list.[7] Humans have long used the Black Moshannon area for recreational, industrial, and subsistence purposes. The Seneca tribe used it as hunting and fishing grounds. European settlers cleared some land for farming, then clear-cut the vast stands of old-growth white pine and eastern hemlock. Black Moshannon State Park rose from the ashes of a depleted forest which had been largely destroyed by wildfire in the years following the lumber era. The forests were rehabilitated by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression in the 1930s. Many of the buildings built by the Civilian Conservation Corps stand in the park today and are protected on the list of National Register of Historic Places in three historic districts. Black Moshannon State Park is open year-round for recreation and has an extensive network of trails which allow hiking, biking, and viewing the bog habitat at the Black Moshannon State Natural Area. The park is in a Pennsylvania Important Bird Area, where bird watchers have recorded 175 species. It is also home to many rare and unusual plants and animals due to its location atop the Allegheny Plateau; the lake is at an elevation of about 1,900 feet (580 m). Much of the park is open for hunting and the lake and creek are open for fishing, boating, and swimming. In winter it is a popular destination for cross-country skiing, and was home to a small downhill skiing area from 1965 to 1982. Picnics and camping are also popular, and the "Friends of Black Moshannon State Park" group promotes the park and all the recreational activities associated with it. HistoryNative Americans Humans have lived in what is now Pennsylvania since at least 10,000 BC. The first settlers were Paleo-Indian nomadic hunters known from their stone tools.[8][9] The hunter-gatherers of the Archaic period, which lasted locally from 7000 to 1000 BC, used a greater variety of more sophisticated stone artefacts. The Woodland period marked the gradual transition to semi-permanent villages and horticulture, between 1000 BC and 1500 AD. Archeological evidence found in the state from this time includes a range of pottery types and styles, burial mounds, pipes, bows and arrow, and ornaments.[8] Black Moshannon Creek is in the West Branch Susquehanna River drainage basin, whose earliest recorded Native American inhabitants were the Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannocks. They were a matriarchial society that lived in large long houses in stockaded villages. Decimated by disease brought by European settlers and warfare with the Five Nations of the Iroquois, by 1675 they had died out, moved away, or been assimilated into other tribes.[9][10] After this, the lands of the West Branch Susquehanna River valley were under the nominal control of the Iroquois.[9] The Iroquois lived in long houses, primarily in what is now New York, and had a strong confederacy which gave them power beyond their numbers.[9] To fill the void left by the demise of the Susquehannocks, the Iroquois encouraged displaced tribes from the east to settle in the West Branch watershed, including the Lenape (or Delaware).[9] The Seneca, members of the Iroquois Confederacy, became inhabitants in the area of Black Moshannon Lake, which was a series of beaver ponds at the time. They and other tribes, including the Lenape, hunted, fished, and traded in the region.[4][9] The Great Shamokin Path, the major native east–west path connecting the Susquehanna and Allegheny River basins, crossed Black Moshannon Creek at a ford a few miles downstream from the park; however, no trails of the indigenous peoples are recorded as having passed through the park itself.[10] The park's 1-mile (1.6 km) Indian Trail for hiking and cross-country skiing recalls such native paths as it runs through an open forest of oak and pine trees, with occasional clearings and a grove of hawthorns.[11][12] The French and Indian War (1754–1763) led to the migration of many Native Americans westward to the Ohio River basin.[9] On November 5, 1768, the British acquired the "New Purchase" from the Iroquois in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, including what is now Black Moshannon State Park.[10] After the American Revolutionary War, Native Americans almost entirely left Pennsylvania.[9] While there are no known archeological sites within Black Moshannon State Park,[4][8][9] the name Moshannon /moʊˈʃænən/ is derived from a Lenape (Delaware) term for Moshannon and Black Moshannon Creeks: Mos'hanna'unk, which means "elk river place".[13][14] The name "Black Moshannon" refers to the dark color of the water, a result of plant tannins from the local vegetation and bog.[4] Lumber era Prior to the arrival of William Penn and his Quaker colonists in 1682, an estimated 90 percent of what is now Pennsylvania was covered with old-growth forest: over 31,000 square miles (80,000 km2) of white pine, eastern hemlock, and a mix of hardwoods.[15] The forests near the three original counties, Philadelphia, Bucks, and Chester, were the first to be harvested, as the early settlers used the readily available timber to build homes, barns, and ships, and cleared the land for agriculture. The demand for lumber slowly increased and by the time of the American Revolution the lumber industry had reached the interior and mountainous regions of Pennsylvania.[15][16] Lumber became one of the leading industries in Pennsylvania.[15] Trees were used for fuel, tannin for the many tanneries that were spread throughout the state, and wood for construction, furniture, and barrel making. Large areas of forest were harvested by colliers to fire iron furnaces. Rifle stocks and shingles were made from Pennsylvania timber, as were a wide variety of household utensils, and the first Conestoga wagons.[15] The Philadelphia–Erie Pike (present day Pennsylvania Route 504) opened the Black Moshannon area to settlers by 1821. The first settlers opened the Antes Tavern along the Pike, trapped fur-bearing animals, and cleared land for farming.[4] By the mid-19th century, the demand for lumber reached the area, where eastern white pine and eastern hemlock covered the surrounding mountainsides. Lumbermen harvested the trees and sent the logs down Black Moshannon and Moshannon Creeks to the West Branch Susquehanna River, then to the Susquehanna Boom and sawmills at Williamsport.[4][16] Lumber was also transported by sled and wagon over the ridges and through the valleys to Philipsburg, Julian, and Unionville.[17]  The Beaver Mill Lumber Company became one of the largest single lumber operations in all of Pennsylvania, and four lumber boomtowns, Beaver Mills, Star Mill, Underwood Mills, and Antes, altered the landscape in the Black Moshannon area.[17] A dam was built at the site of an old beaver dam,[18] and the mill ponds for the lumber mills flooded the old beaver ponds. The communities featured general stores, blacksmith shops, liveries, taverns, schools, and even a ten-pin bowling alley. The area helped to meet the nation's need for timber in mining operations, construction, and railroads.[4] A number of trails in the park today recall this time. The 1.1-mile (1.8 km) Hay Road Trail was used by farmers who collected hay at the wetlands, and connects the cabin area with the lake. The 0.8-mile (1.3 km) Seneca Trail for cross-country skiing and hiking passes through a second growth forest of oak and cherry trees that shade the stumps of the old growth pines harvested during the lumber era.[11][12] The Shingle Mill Trail is a 3.67-mile (5.91 km) path that begins at the main parking area near the dam on Black Moshannon Lake and follows the banks of Black Moshannon Creek to the Allegheny Front Trail and back.[19][12] The remains of Star Mill, a sawmill built in 1879 that operated until the end of the lumber era, are on the 2.1-mile (3.4 km) Star Mill Trail. This loop trail for hiking and cross-country skiing is nearly flat, with a view of Black Moshannon Lake.[12] This boom era was not to last; before long the lumber was gone, leaving a barren landscape devastated by erosion and wildfires. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania bought thousands of acres of deforested and burned land, then began the project of reforestation. By the 1930s, the land that became Black Moshannon State Park was already a place for picnics and camping, on the aptly named "Tent Hill", and people swam and fished in the old mill pond.[4] The 0.2-mile (320 m) Tent Hill Trail still runs from the campsites to the Black Moshannon Lake beach.[19][12] Civilian Conservation Corps The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a work relief program for young men from unemployed families, established in 1933. As part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal legislation, it was designed to combat unemployment during the Great Depression. The CCC operated in every U.S. state.[20] The original facilities at Black Moshannon State Park were constructed by the CCC from 1933 to 1937, one of many projects it undertook throughout central Pennsylvania.[4][21] Beaver Meadow CCC Camp S-71 was built in May 1933 near the abandoned village of Beaver Mills, and was one of the first to expand recreational facilities in Pennsylvania.[5] More than 200 young men moved in and began the work of conserving soil, water, and timber in the area. They cut roads through the growing forest to aid in fighting the wildfires that sprang up, and planted many acres of red pines as part of the reforestation effort.[22] Most of the CCC-built park facilities are still in use today, including log cabins, picnic pavilions, a food concession stand, and miles of trails. Early on, the CCC constructed a dam at Black Moshannon Lake, on the site of the former mill pond dam.[4][18][21] CCC Camp S-71 closed in January 1937 and Black Moshannon State Park officially opened that same year.[23] Historic districts In 1987, three separate historic districts incorporating the existing CCC structures in Black Moshannon State Park were placed on the National Register of Historic Places.[24] The structures in all three districts were built between 1933 and 1937 and are designated as part of either the Beach and Day Use, Family Cabin, or Maintenance Historic Districts. Eighteen structures in the Beach and Day Use Historic District are protected as contributing properties, including seven "standard" pavilions, a larger picnic shelter, and three water pump shelters. These last were built of native stone and covered with pebbles, and have since been converted to small picnic pavilions. The concession building, beach bathhouse, and museum are also protected.[18] Four open pit latrines with wane edge siding and hipped roofs were also contributing structures to the Beach and Day Use district.[18] The Family Cabin Historic District consists of 16 contributing properties: 13 log cabins, one lodge, and two latrines. Cabins 1–12, half with one room and half with two, are in a line along a road, similar to 1930s motor courts. The cabin layout at Black Moshannon State Park is unique compared to CCC-built cabins at other Pennsylvania state parks.[5] The cabins at the other parks reflect the "rustic" style of cabin layout promoted by the National Park Service. The Lodge, also known as Cabin 13, is a large rectangular clapboard-sided building with a stone fireplace, while Cabin 14 is L-shaped with an open porch. Two pit latrines built by the CCC were also contributing structures.[5] The Maintenance Historic District includes four CCC-built structures.[25] The storage building is a wood-frame structure with a gable roof, similar to military storage buildings built in the 1930s and 1940s. A three-bay garage of standard military design is included in this historic district, as was the gas pump house with an extended eave to protect the gas pumps. The Park Ranger's residence is a 1+1⁄2-story gable-roofed house, with modern vinyl siding.[25] Modern era Since its establishment in 1937, Black Moshannon State Park has undergone many changes. In 1941, Governor Arthur James announced plans to expand the park to 1,000 acres (400 ha) by annexing surrounding state forest land.[26] "Black Moshannon Airport" was built on land taken from the state park and Moshannon State Forest just prior to the Second World War,[17] was operational by 1942,[27] and renamed "Mid-State Airport" in 1962.[28] As of 2023, it is officially known as "Mid-State Regional Airport" and covers 500 acres (200 ha).[29] While the airport was designated a Keystone Opportunity Zone to encourage business growth,[30] there are limitations in state law that prohibit any further development on park or forest lands.[31]  The park was the site of a ski resort from the 1960s until 1982. The state legislature authorized "construction of ski facilities" at the park in 1961,[32] which were operational by 1965.[33] Although managed by the state, a commercial operator was sought as early as 1969,[34] and in 1980 it was leased to a private contractor, before being closed in 1982.[23][35] The ski area was primitive by modern standards: skiers were lifted to the top of the slope by one of two tow ropes or Poma lifts,[34] and the slopes had about 250 feet (76 m) of vertical drop.[36] As of 2020, the ski lodge, renamed Cabin 20, can be rented out by park visitors,[37] while the Ski Slope Trail is a 2-mile (3.2 km) hiking trail that passes near the former ski slope. It begins at the beach parking lot, climbs Rattlesnake Mountain, and crosses Pennsylvania Route 504 near a historical marker for the Philadelphia–Erie Turnpike.[12]  On November 11, 1954, the park was officially named "Black Moshannon State Park" by the Pennsylvania Geographic Board. The CCC-built dam forming Black Moshannon Lake was replaced in the 1950s, and the current Kephart Dam was built in 1974.[18][38] The park experienced major developments between 1971 and 1980.[23] Time has brought changes to the park's CCC-built structures: the original picnic pavilion 6 collapsed under snow in 1994,[18] the museum became the Environmental Learning Center, most of the latrines are gone, and six modern cabins and two deluxe cottages have been built in the Cabin Historic District. As of 2020, other post-war facilities include the park office, boat launches, showerhouses, electric vehicle charging stations, and modern restroom and shower facilities.[37][39] There is a wastewater treatment plant near the dam for effluent from the park and some private homes.[40] In 2019, the state paid $299,000 to the Philipsburg Rod and Gun Club, which had leased 23 acres (9.3 ha) near the Organized Group Tenting area in the park for over 60 years. The state terminated the lease over environmental contamination from lead shot.[41][42]  By the 1980s, the park started to receive official recognition for its unique resources. The three Historic Districts were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1987 in recognition of their CCC-built structures.[24] That same year the state celebrated Black Moshannon State Park's "50th Anniversary".[43] In 1994, the DCNR established the "Black Moshannon Bog Natural Area" as part of a program to recognize areas of "unique scenic, geologic or ecological value".[44][45] In 1997 the park's Important Bird Area (IBA) was one of the first 73 IBAs established in Pennsylvania.[46] By 2001 yearly attendance at Black Moshannon State Park was over 350,000.[19] As of 2020, the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) Bureau of Parks, which administers all 121 Pennsylvania state parks, had chosen Black Moshannon as one of its "25 Must-see Pennsylvania State Parks", citing it as home to the "largest reconstituted bog in Pennsylvania".[7] Geology and climate The rocks underlying the Black Moshannon Creek drainage basin are primarily shale, sandstone, and coal.[47] Three major rock formations are present in Black Moshannon State Park, all from the Carboniferous period. These sedimentary rocks formed in or near shallow seas roughly 300 to 350 million years ago.[48] The Mississippian Burgoon Formation is composed of buff-colored sandstone and conglomerate. The late Mississippian Mauch Chunk Formation is formed with grayish-red shale, siltstone, sandstone, and conglomerate. The third is the early Pennsylvanian Pottsville Formation, which is a gray conglomerate that may contain sandstone, siltstone, and shale, as well as anthracite coal.[48][49] The park is at an elevation of 1,919 feet (585 m) atop the Allegheny Plateau,[1] just west of the Allegheny Front, a steep escarpment which rises 1,300 feet (400 m) in 4 miles (6.4 km), and marks the transition between the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians to the east and the Allegheny Plateau to the west. The Allegheny Plateau and Appalachian mountains were all formed in the Alleghenian orogeny some 300 million years ago, when Gondwana (specifically what became Africa) and what became North America collided, forming Pangaea.[48][50] The lake within the park is at an elevation of about 1,900 feet (580 m), and the park itself sits in a natural basin. The basin and the underlying sandstone trap water and thus form the lake and surrounding bogs.[44][51] The higher elevation leads to a cooler climate, and the basin helps trap denser, cooler air, leading to longer winters and milder summers.[19] The cooler climate also means the park is home to animals and plants typically found much further north.[19] The Allegheny Plateau has a continental climate, with occasional severe low temperatures in winter and average daily temperature ranges of 20 °F (11 °C) in winter and 26 °F (14 °C) in summer.[52] In 1972, long-term average monthly temperatures ranged from a high of 66.8 °F (19.3 °C) in July to a low of 26.2 °F (−3.2 °C) in January.[53] The mean annual precipitation for the Black Moshannon Creek watershed is 40 to 42 inches (1016 to 1067 mm).[47] The soil in the park is mostly derived from sandstone and as such does not have much capacity to neutralize acid rain.[40] The highest recorded temperature at the park was 97 °F (36 °C) in 1988, and the record low was −25 °F (−32 °C) in 1994.[54]

EcologyWithin Black Moshannon State Park there is a State Park Natural Area protecting the bogs.[44] The park itself is part of a much larger Important Bird Area, which includes most of the surrounding state forest, airport, and private properties.[40] Bog Natural Area The bogs at the park contain large amounts of sphagnum moss; this decomposes very slowly, causing layers of dead moss to build up at the bottom of the bog, creating peat.[44] In 1994, 1,592 acres (644 ha) of bog at the state park were protected as the "Black Moshannon Bog Natural Area";[44] this was originally conceived as part of the State Parks 2000 strategic plan of the DCNR, and fourteen years later the total area of bog protected as a Natural Area had increased to 1,992 acres (806 ha).[45] Most bogs exist in glaciated areas, but Black Moshannon State Park is on the Allegheny Plateau. This area was not covered by glaciers during the last ice age. The bogs formed here because of the beds of sandstone that lie flat, a short distance below the surface of the earth. The sandstone formations in the park do not absorb water very well, so any depression in them will collect water, as has happened here.[44] The bogs extend the shores of the lake. Migratory shorebirds that visit here include greater and lesser yellowlegs, least sandpiper, solitary sandpiper, and the spotted sandpiper, which has been confirmed as using the IBA as a breeding grounds.[40] The water in the bog is low in nutrients and high in acidity, which makes it difficult for most plants to live there. Only specialized plants can thrive in the park bogs: there are three species of carnivorous plants and seventeen varieties of orchid. Wild cranberries and blueberries grow in the bog along with sedges, leatherleaf shrubs, Arctic cotton grass, and viburnums. The bogs are all protected by the state of Pennsylvania.[44] Wildlife White-tailed deer, wild turkey, ruffed grouse, opossum, raccoon, hawks, chipmunks, porcupine, woodpeckers, and flying, red, and eastern gray squirrels are all fairly common in the park. Black bears also inhabit Black Moshannon State Park.[44] Many of these animals were decimated due to the effects of deforestation, pollution and unregulated hunting and trapping during the late 19th century.[55] Hunting controls established by the Pennsylvania Game Commission and the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps and Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources in re-establishing the second growth forest have led to the strong comeback of game species at Black Moshannon State Park and throughout the forests of Pennsylvania.[55] The lake is home to American beavers, as well as great blue heron, swans, snow geese, common loons, and many other types of waterfowl, with Canada goose, ring-necked duck, mallard, and wood duck the most commonly seen. The bogs, marshes, and swamps contain frogs and salamanders, and provide a habitat for carnivorous plants like the pitcher plant and sundew. Black Moshannon State Park is home to many common species of songbirds, including ovenbirds.[40][44] The conifer and mixed-forests of the park and its surroundings provide habitats for northern saw-whet owl, blue-headed vireo, hermit thrush, dark-eyed junco, and magnolia, pine, yellow-rumped, Blackburnian, and black-throated green warblers. The deciduous forests provide habitats for songbirds, such as scarlet tanager and red-eyed vireo.[40] An outbreak of the non-native gypsy moth in the mid-1980s nearly devastated the woods in a small valley. Selective timber cuts harvested the trees that were affected by species of moth. Today the 1.2-mile (1.9 km) Sleepy Hollow Trail for hiking, biking, and cross-country skiing loops through the new growth in the area, which provides an ideal habitat for populations of white-tailed deer and wild turkey.[11][12] Important Bird AreaPennsylvania's "Black Moshannon State Park & State Forest" Important Bird Area (IBA) encompasses 45,667 acres (18,481 ha). The land includes parts of the state park and surrounding Moshannon State Forest, as well as Pennsylvania State Game Lands No. 33, Mid-State Regional Airport (which borders both the park and the forest), and some other nearby parcels of private land. The Pennsylvania Audubon Society has designated 3,374 acres (1,365 ha) of Black Moshannon State Park as an IBA, which is an area designated as a globally important habitat for the conservation of bird populations.[40][56]  Ornithologists and bird watchers have recorded a total of 175 species at the IBA. Several factors contribute to the high total of bird species observed: there is a large area of forest in the IBA, as well as great habitat diversity. The location of the IBA along the Allegheny Front also contributes to the diverse bird populations.[40] Black Moshannon Lake and the bogs of the Natural Area are especially important to the IBA. They serve as a stopover for migratory waterfowl and shorebirds. Waterfowl observed at the park include pied-billed and Slavonian grebes, common loon, American black duck, ruddy duck, blue-winged and green-winged teal, tundra swan, long-tailed duck, hooded and red-breasted merganser, greater and lesser scaup, northern pintail, bufflehead, American wigeon, and northern shoveler.[40] Pennsylvania IBA #33 is on the Allegheny Front, which is along a prime migratory path for a variety of birds of prey. The golden eagle, bald eagle, osprey, and northern harrier pass through the area during their annual migration periods. It is possible that the bald eagle may nest within the IBA, but this has not been confirmed. Raptors which do nest in the forests of the IBA include the northern goshawk, red-shouldered, broad-winged, red-tailed, sharp-shinned, and Cooper's hawks.[40] The cool, damp habitat provided by the bogs at Black Moshannon State Park provides a home for some birds that are at the southern limit of their habitat in central Pennsylvania. The Canada warbler and northern waterthrush nest in the bogs, as do the alder flycatcher, common yellowthroat, swamp sparrow, red-winged blackbird, and gray catbird. The olive-sided flycatcher, which is designated as locally extinct in Pennsylvania, has been seen during the breeding season at Black Moshannon State Natural Area. Bird watchers have observed nesting barred owls in the IBA, as well as Virginia rail and sora.[40] RecreationCabins, camping, swimming, and picnics Twenty-one cabins can be used by visitors at Black Moshannon State Park. Thirteen are rustic cabins, built by the CCC, with electric lights, a kitchen stove and a wood-burning stove, refrigerator, and bunk beds. Six are modern cabins, including the former ski lodge,[39] with electric heat, a bedroom, living room, kitchen, and bath. There are also two deluxe camping cottages with electric heat and similar amenities as the rustic cabins. All cabin renters need to bring their own household items such as linens and cookware.[21][37] There are seventy-two campsites at Black Moshannon State Park. Each campsite has access to washhouses with flush toilets, showers, and laundry tubs. The campsites also have fire rings and picnic tables. There is also an organized group tenting area, which can accommodate up to 60 persons.[37] Some sites allow pets; there are also twelve full hook-up sites available. These have electric service, water and sewer hook-ups as well. Nine sites are tent-only. The sandy beach on Black Moshannon Lake is open from Memorial Day weekend through Labor Day weekend, and the beach bathhouse was built by the CCC.[37] Beginning in 2008, lifeguards will not be posted at the beach.[57] There are eight picnic pavilions built by the CCC in the park, which can be reserved for a fee. In addition to the pavilions, Black Moshannon State Park has 250 picnic tables in four large picnic areas. The use of these picnic tables and unreserved pavilions is first come, first served, and they are free of charge.[37] Some modern activities are prohibited in Black Moshannon State Park. The operation of drones and similar radio controlled devices is prohibited. All-terrain vehicle usage is also prohibited and closely monitored by DCNR. Further, removing any natural items is illegal as is firewood cutting without a permit. Boating, fishing, and hunting Boating is a popular use of the waters of Black Moshannon Lake, which covers 250 acres (100 ha). Canoes, sailboats, and electric motor boats are all permitted on Black Moshannon Lake, provided they are properly registered with the state.[37] Edward Gertler, author of a series of canoeing books, calls Black Moshannon Creek "about the best whitewater run in the West Branch Susquehanna Watershed" in Keystone Canoeing,[58] and the first 13.2-mile (21.2 km) stretch of Class 2+ whitewater for canoeing and kayaking begins in the park, just downstream of the dam. Cold water fishing is available in Black Moshannon Creek and several of its tributaries, where anglers will find rainbow and brown trout which have been stocked there for sport fishing by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. Black Moshannon Lake's waters are warmer than those of the creek, and so hold many different species of fish, including largemouth bass, yellow perch, chain pickerel, bullhead catfish, northern pike, bluegill, and crappie.[37] Hunting is permitted in most of Black Moshannon State Park. It helps to prevent an overpopulation of animals and the resulting overbrowsing of the understory.[55] The most common game species are ruffed grouse, eastern gray squirrel, wild turkey, and white-tailed deer. However, the hunting of groundhogs is prohibited.[37] TrailsThere are 21 miles (34 km) of trails at Black Moshannon State Park; all are open to hiking, most are open to cross-country skiing during the winter months, and select trails are open to snowmobiles and mountain bikes.[12] The park is especially popular among cross-country skiing enthusiasts due to its high elevation.[11] Skiers will find trails that are largely free of rocks, with a layer of grass beneath the snow. Sleepy Hollow, Seneca, Indian, and Hay Road Trails are most frequently used.[11] Eight of the park's fourteen trails are described above, the remaining six follow.

Friends of Black Moshannon State Park The Friends of Black Moshannon State Park is a volunteer organization that promotes the recreational use of the park through a summer festival. The group also works with the park staff to maintain the park lands, serve as campground hosts, survey the eastern bluebird population, and organize conservation projects.[59] The Summer Festival usually takes place over the fourth weekend of July. Events at the festival recall the lumbering history of the park. Log rolling, axe throwing, and cross-cut sawing events are held, as are horseshoe and seed spitting contests.[59] Black Moshannon Lake is open to canoe races and fishing. A Saturday night bonfire party is held at the beach, with music and refreshments.[59] Nearby state parksThe following state parks are within 30 miles (48 km) of Black Moshannon State Park:[2][60][61]

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Black Moshannon State Park.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||