|

Book of the Dead

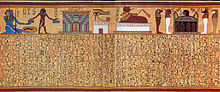

The Book of the Dead is the name given to an ancient Egyptian funerary text generally written on papyrus and used from the beginning of the New Kingdom (around 1550 BC) to around 50 BC.[1] "Book" is the closest term to describe the loose collection of texts[2] consisting of a number of magic spells intended to assist a dead person's journey through the Duat, or underworld, and into the afterlife and written by many priests over a period of about 1,000 years. In 1842, the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius introduced for these texts the German name Todtenbuch (modern spelling Totenbuch), translated to English as 'Book of the Dead'. The original Egyptian name for the text, transliterated rw nw prt m hrw,[3] is translated as Spells of Coming Forth by Day.[4] The Book of the Dead, which was placed in the coffin or burial chamber of the deceased, was part of a tradition of funerary texts which includes the earlier Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts, which were painted onto objects, not written on papyrus. Some of the spells included in the book were drawn from these older works and date to the 3rd millennium BC. Other spells were composed later in Egyptian history, dating to the Third Intermediate Period (11th to 7th centuries BC). A number of the spells which make up the Book continued to be separately inscribed on tomb walls and sarcophagi, as the spells from which they originated always had been. There was no single or canonical Book of the Dead. The surviving papyri contain a varying selection of religious and magical texts and vary considerably in their illustration. Some people seem to have commissioned their own copies of the Book of the Dead, perhaps choosing the spells they thought most vital in their own progression to the afterlife. The Book of the Dead was most commonly written in hieroglyphic or hieratic script on a papyrus scroll, and often illustrated with vignettes depicting the deceased and their journey into the afterlife. The finest extant example of the Egyptian in antiquity is the Papyrus of Ani. Ani was an Egyptian scribe. It was discovered in Luxor in 1888 by Egyptians trading in illegal antiquities. It was acquired by E. A. Wallis Budge, as described in his autobiography By Nile and Tigris in 1888 and was taken to the British Museum, where it remains. Examples in museums

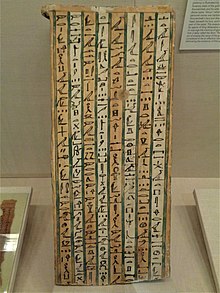

Development The Book of the Dead developed from a tradition of funerary manuscripts dating back to the Egyptian Old Kingdom. The first funerary texts were the Pyramid Texts, first used in the Pyramid of King Unas of the 5th Dynasty, around 2400 BC.[5] These texts were written on the walls of the burial chambers within pyramids, and were exclusively for the use of the pharaoh (and, from the 6th Dynasty, the queen). The Pyramid Texts were written in an unusual hieroglyphic style; many of the hieroglyphs representing humans or animals were left incomplete or drawn mutilated, most likely to prevent them causing any harm to the dead pharaoh.[6] The purpose of the Pyramid Texts was to help the dead king take his place amongst the gods, in particular to reunite him with his divine father Ra; at this period the afterlife was seen as being in the sky, rather than the underworld described in the Book of the Dead.[6] Towards the end of the Old Kingdom, the Pyramid Texts ceased to be an exclusively royal privilege, and were adopted by regional governors and other high-ranking officials.[6] In the Middle Kingdom, a new funerary text emerged, the Coffin Texts. The Coffin Texts used a newer version of the language, new spells, and included illustrations for the first time. The Coffin Texts were most commonly written on the inner surfaces of coffins, though they are occasionally found on tomb walls or on papyri.[6] The Coffin Texts were available to wealthy private individuals, vastly increasing the number of people who could expect to participate in the afterlife; a process which has been described as the "democratization of the afterlife".[7] The Book of the Dead first developed in Thebes toward the beginning of the Second Intermediate Period, around 1700 BC. The earliest known occurrence of the spells included in the Book of the Dead is from the coffin of Queen Mentuhotep, of the 16th Dynasty, where the new spells were included amongst older texts known from the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts. Some of the spells introduced at this time claim an older provenance; for instance the rubric to spell 30B states that it was discovered by the Prince Hordjedef in the reign of King Menkaure, many hundreds of years before it is attested in the archaeological record.[8] By the 17th Dynasty, the Book of the Dead had become widespread not only for members of the royal family, but courtiers and other officials as well. At this stage, the spells were typically inscribed on linen shrouds wrapped around the dead, though occasionally they are found written on coffins or on papyrus.[9] The New Kingdom saw the Book of the Dead develop and spread further. The famous Spell 125, the 'Weighing of the Heart', is first known from the reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, c. 1475 BC. From this period onward the Book of the Dead was typically written on a papyrus scroll, and the text illustrated with vignettes. During the 19th Dynasty in particular, the vignettes tended to be lavish, sometimes at the expense of the surrounding text.[10] In the Third Intermediate Period, the Book of the Dead started to appear in hieratic script, as well as in the traditional hieroglyphics. The hieratic scrolls were a cheaper version, lacking illustration apart from a single vignette at the beginning, and were produced on smaller papyri. At the same time, many burials used additional funerary texts, for instance the Amduat.[11]  During the 25th and 26th Dynasties, the Book of the Dead was updated, revised and standardized. Spells were ordered and numbered consistently for the first time. This standardized version is known today as the 'Saite recension', after the Saite (26th) Dynasty. In the Late period and Ptolemaic period, the Book of the Dead continued to be based on the Saite recension, though increasingly abbreviated towards the end of the Ptolemaic period. New funerary texts appeared, including the Book of Breathing and Book of Traversing Eternity. The last use of the Book of the Dead was in the 1st century BC, though some artistic motifs drawn from it were still in use in Roman times.[12] Spells The Book of the Dead is made up of a number of individual texts and their accompanying illustrations. Most sub-texts begin with the word r(ꜣ), which can mean "mouth", "speech", "spell", "utterance", "incantation", or "chapter of a book". This ambiguity reflects the similarity in Egyptian thought between ritual speech and magical power.[14] In the context of the Book of the Dead, it is typically translated as either chapter or spell. In this article, the word spell is used. At present, some 192 spells are known,[15] though no single manuscript contains them all. They served a range of purposes. Some are intended to give the deceased mystical knowledge in the afterlife, or perhaps to identify them with the gods: for instance, Spell 17 is an obscure and lengthy description of the god Atum.[16] Others are incantations to ensure the different elements of the dead person's being were preserved and reunited, and to give the deceased control over the world around him. Still others protect the deceased from various hostile forces or guide him through the underworld past various obstacles. Famously, two spells also deal with the judgment of the deceased in the Weighing of the Heart ritual. Such spells as 26–30, and sometimes spells 6 and 126, relate to the heart and were inscribed on scarabs.[17] The texts and images of the Book of the Dead were magical as well as religious. Magic was as legitimate an activity as praying to the gods, even when the magic was aimed at controlling the gods themselves.[18] Indeed, there was little distinction for the Ancient Egyptians between magical and religious practice.[19] The concept of magic (heka) was also intimately linked with the spoken and written word. The act of speaking a ritual formula was an act of creation;[20] there is a sense in which action and speech were one and the same thing.[19] The magical power of words extended to the written word. Hieroglyphic script was held to have been invented by the god Thoth, and the hieroglyphs themselves were powerful. Written words conveyed the full force of a spell.[20] This was even true when the text was abbreviated or omitted, as often occurred in later Book of the Dead scrolls, particularly if the accompanying images were present.[21] The Egyptians also believed that knowing the name of something gave power over it; thus, the Book of the Dead equips its owner with the mystical names of many of the entities he would encounter in the afterlife, giving him power over them.[22]  The spells of the Book of the Dead made use of several magical techniques which can also be seen in other areas of Egyptian life. A number of spells are for magical amulets, which would protect the deceased from harm. In addition to being represented on a Book of the Dead papyrus, these spells appeared on amulets wound into the wrappings of a mummy.[18] Everyday magic made use of amulets in huge numbers. Other items in direct contact with the body in the tomb, such as headrests, were also considered to have amuletic value.[23] A number of spells also refer to Egyptian beliefs about the magical healing power of saliva.[18] OrganizationAlmost every Book of the Dead was unique, containing a different mixture of spells drawn from the corpus of texts available. For most of the history of the Book of the Dead there was no defined order or structure.[24] In fact, until Paul Barguet's 1967 "pioneering study" of common themes between texts,[25] Egyptologists concluded there was no internal structure at all.[26] It is only from the Saite period (26th Dynasty) onwards that there is a defined order.[27] The Books of the Dead from the Saite period tend to organize the Chapters into four sections:

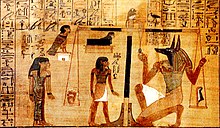

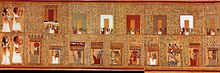

Egyptian concepts of death and afterlife The spells in the Book of the Dead depict Egyptian beliefs about the nature of death and the afterlife. The Book of the Dead is a vital source of information about Egyptian beliefs in this area. PreservationOne aspect of death was the disintegration of the various kheperu, or modes of existence.[28] Funerary rituals served to re-integrate these different aspects of being. Mummification served to preserve and transform the physical body into sah, an idealized form with divine aspects;[29] the Book of the Dead contained spells aimed at preserving the body of the deceased, which may have been recited during the process of mummification.[30] The heart, which was regarded as the aspect of being which included intelligence and memory, was also protected with spells, and in case anything happened to the physical heart, it was common to bury jeweled heart scarabs with a body to provide a replacement. The ka, or life-force, remained in the tomb with the dead body, and required sustenance from offerings of food, water and incense. In case priests or relatives failed to provide these offerings, Spell 105 ensured the ka was satisfied.[31] The name of the dead person, which constituted their individuality and was required for their continued existence, was written in many places throughout the Book, and spell 25 ensured the deceased would remember their own name.[32] The ba was a free-ranging spirit aspect of the deceased. It was the ba, depicted as a human-headed bird, which could "go forth by day" from the tomb into the world; spells 61 and 89 acted to preserve it.[33] Finally, the shut, or shadow of the deceased, was preserved by spells 91, 92 and 188.[34] If all these aspects of the person could be variously preserved, remembered, and satiated, then the dead person would live on in the form of an akh. An akh was a blessed spirit with magical powers who would dwell among the gods.[35] AfterlifeThe nature of the afterlife which the dead people enjoyed is difficult to define, because of the differing traditions within Ancient Egyptian religion. In the Book of the Dead, the dead were taken into the presence of the god Osiris, who was confined to the subterranean Duat. There are also spells to enable the ba or akh of the dead to join Ra as he travelled the sky in his sun-barque, and help him fight off Apep.[36] As well as joining the Gods, the Book of the Dead also depicts the dead living on in the 'Field of Reeds', a paradisiac likeness of the real world.[37] The Field of Reeds is depicted as a lush, plentiful version of the Egyptian way of living. There are fields, crops, oxen, people and waterways. The deceased person is shown encountering the Great Ennead, a group of gods, as well as his or her own parents. While the depiction of the Field of Reeds is pleasant and plentiful, it is also clear that manual labour is required. For this reason burials included a number of statuettes named shabti, or later ushebti. These statuettes were inscribed with a spell, also included in the Book of the Dead, requiring them to undertake any manual labour that might be the owner's duty in the afterlife.[38] It is also clear that the dead not only went to a place where the gods lived, but that they acquired divine characteristics themselves. In many occasions, the deceased is mentioned as "The Osiris – [Name]" in the Book of the Dead.  The path to the afterlife as laid out in the Book of the Dead was a difficult one. The deceased was required to pass a series of gates, caverns and mounds guarded by supernatural creatures.[40] These terrifying entities were armed with enormous knives and are illustrated in grotesque forms, typically as human figures with the heads of animals or combinations of different ferocious beasts. Their names—for instance, "He who lives on snakes" or "He who dances in blood"—are equally grotesque. These creatures had to be pacified by reciting the appropriate spells included in the Book of the Dead; once pacified they posed no further threat, and could even extend their protection to the dead person.[41] Another breed of supernatural creatures was 'slaughterers' who killed the unrighteous on behalf of Osiris; the Book of the Dead equipped its owner to escape their attentions.[42] As well as these supernatural entities, there were also threats from natural or supernatural animals, including crocodiles, snakes, and beetles.[43] Judgment  The deceased's first task was to correctly address each of the forty-two Assessors of Maat by name, while reciting the sins they did not commit during their lifetime.[44] This process allowed the dead to demonstrate that they knew each of the judges' names or Ren and established that they were pure, and free of sin. If all the obstacles of the Duat could be negotiated, the deceased would be judged in the "Weighing of the Heart" ritual, depicted in Spell 125. The deceased was led by the god Anubis into the presence of Osiris. There, the dead person swore that he had not committed any sin from a list of 42 sins,[45] reciting a text known as the "Negative Confession". Then the dead person's heart was weighed on a pair of scales, against the goddess Maat, who embodied truth and justice. Maat was often represented by an ostrich feather, the hieroglyphic sign for her name.[46] At this point, there was a risk that the deceased's heart would bear witness, owning up to sins committed in life; Spell 30B guarded against this eventuality. If the scales balanced, this meant the deceased had led a good life. Anubis would take them to Osiris and they would find their place in the afterlife, becoming maa-kheru, meaning "vindicated" or "true of voice".[47] If the heart was out of balance with Maat, then another fearsome beast called Ammit, the Devourer, stood ready to eat it and put the dead person's afterlife to an early and rather unpleasant end.[48] This scene is remarkable not only for its vividness but as one of the few parts of the Book of the Dead with any explicit moral content. The judgment of the dead and the Negative Confession were a representation of the conventional moral code which governed Egyptian society. For every "I have not..." in the Negative Confession, it is possible to read an unexpressed "Thou shalt not".[49] While the Ten Commandments of Jewish and Christian ethics are rules of conduct laid down by a perceived divine revelation, the Negative Confession is more a divine enforcement of everyday morality.[50] Views differ among Egyptologists about how far the Negative Confession represents a moral absolute, with ethical purity being necessary for progress to the Afterlife. John Taylor points out the wording of Spells 30B and 125 suggests a pragmatic approach to morality; by preventing the heart from contradicting him with any inconvenient truths, it seems that the deceased could enter the afterlife even if their life had not been entirely pure.[48] Ogden Goelet says "without an exemplary and moral existence, there was no hope for a successful afterlife",[49] while Geraldine Pinch suggests that the Negative Confession is essentially similar to the spells protecting from demons, and that the success of the Weighing of the Heart depended on the mystical knowledge of the true names of the judges rather than on the deceased's moral behavior.[51] Producing a Book of the Dead A Book of the Dead was produced to order by scribes. They were commissioned by people in preparation for their own funerals, or by the relatives of someone recently deceased. They were expensive items; one source gives the price of a Book of the Dead scroll as one deben of silver,[52] perhaps half the annual pay of a laborer.[53] Papyrus itself was evidently costly, as there are many instances of its re-use in everyday documents, creating palimpsests. In one case, a Book of the Dead was written on second-hand papyrus.[54] Most owners of the Book of the Dead were evidently part of the social elite; they were initially reserved for the royal family, but later papyri are found in the tombs of scribes, priests and officials. Most owners were men, and generally the vignettes included the owner's wife as well. Towards the beginning of the history of the Book of the Dead, there are roughly ten copies belonging to men for every one for a woman. However, during the Third Intermediate Period, two were for women for every one for a man; and women owned roughly a third of the hieratic papyri from the Late and Ptolemaic Periods.[55]  The dimensions of a Book of the Dead could vary widely; the longest is 40 m long while some are as short as 1 m. They are composed of sheets of papyrus joined together, the individual papyri varying in width from 15 cm to 45 cm. The scribes working on Book of the Dead papyri took more care over their work than those working on more mundane texts; care was taken to frame the text within margins, and to avoid writing on the joints between sheets. The words peret em heru, or coming forth by day sometimes appear on the reverse of the outer margin, perhaps acting as a label.[54]  Books were often prefabricated in funerary workshops, with spaces being left for the name of the deceased to be written in later.[56] For instance, in the Papyrus of Ani, the name "Ani" appears at the top or bottom of a column, or immediately following a rubric introducing him as the speaker of a block of text; the name appears in a different handwriting to the rest of the manuscript, and in some places is mis-spelt or omitted entirely.[53] The text of a New Kingdom Book of the Dead was typically written in cursive hieroglyphs, most often from left to right, but also sometimes from right to left. The hieroglyphs were in columns, which were separated by black lines – a similar arrangement to that used when hieroglyphs were carved on tomb walls or monuments. Illustrations were put in frames above, below, or between the columns of text. The largest illustrations took up a full page of papyrus.[57] From the 21st Dynasty onward, more copies of the Book of the Dead are found in hieratic script. The calligraphy is similar to that of other hieratic manuscripts of the New Kingdom; the text is written in horizontal lines across wide columns (often the column size corresponds to the size of the papyrus sheets of which a scroll is made up). Occasionally a hieratic Book of the Dead contains captions in hieroglyphic. The text of a Book of the Dead was written in both black and red ink, regardless of whether it was in hieroglyphic or hieratic script. Most of the text was in black, with red ink used for the titles of spells, opening and closing sections of spells, the instructions to perform spells correctly in rituals, and also for the names of dangerous creatures such as the demon Apep.[58] The black ink used was based on carbon, and the red ink on ochre, in both cases mixed with water.[59] The style and nature of the vignettes used to illustrate a Book of the Dead varies widely. Some contain lavish color illustrations, even making use of gold leaf. Others contain only line drawings, or one simple illustration at the opening.[60] Book of the Dead papyri were often the work of several different scribes and artists whose work was literally pasted together.[54] It is usually possible to identify the style of more than one scribe used on a given manuscript, even when the manuscript is a shorter one.[58] The text and illustrations were produced by different scribes; there are a number of Books where the text was completed but the illustrations were left empty.[61] Discovery, translation, interpretation and preservation The existence of the Book of the Dead was known as early as the Middle Ages, well before its contents could be understood. Since it was found in tombs, it was evidently a document of a religious nature, and this led to the widespread but mistaken belief that the Book of the Dead was the equivalent of a Bible or Qur'an.[62][63] In 1842 Karl Richard Lepsius published a translation of a manuscript dated to the Ptolemaic era and coined the name "Book of The Dead" (das Todtenbuch). He also introduced the spell numbering system which is still in use, identifying 165 different spells.[15] Lepsius promoted the idea of a comparative edition of the Book of the Dead, drawing on all relevant manuscripts. This project was undertaken by Édouard Naville, starting in 1875 and completed in 1886, producing a three-volume work including a selection of vignettes for every one of the 186 spells he worked with, the more significant variations of the text for every spell, and commentary. In 1867 Samuel Birch of the British Museum published the first extensive English translation.[64] In 1876 he published a photographic copy of the Papyrus of Nebseny.[65] The work of E. A. Wallis Budge, Birch's successor at the British Museum, is still in wide circulation – including both his hieroglyphic editions and his English translations of the Papyrus of Ani, though the latter are now considered inaccurate and out-of-date.[66] More recent translations in English have been published by Thomas George Allen (1974) and Raymond O. Faulkner (1972).[67] As more work has been done on the Book of the Dead, more spells have been identified, and the total now stands at 192.[15] In the 1970s, Ursula Rößler-Köhler at the University of Bonn began a working group to develop the history of Book of the Dead texts. This later received sponsorship from the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the German Research Foundation, in 2004 coming under the auspices of the German Academies of Sciences and Arts. Today the Book of the Dead Project, as it is called, maintains a database of documentation and photography covering 80% of extant copies and fragments from the corpus of Book of the Dead texts, and provides current services to Egyptologists.[68] It is housed at the University of Bonn, with much material available online.[69] Affiliated scholars are authoring a series of monograph studies, the Studien zum Altägyptischen Totenbuch, alongside a series that publishes the manuscripts themselves, Handschriften des Altägyptischen Totenbuches.[70] Both are in print by Harrassowitz Verlag. Orientverlag has released another series of related monographs, Totenbuchtexte, focused on analysis, synoptic comparison, and textual criticism. Research work on the Book of the Dead has always posed technical difficulties thanks to the need to copy very long hieroglyphic texts. Initially, these were copied out by hand, with the assistance either of tracing paper or a camera lucida. In the mid-19th century, hieroglyphic fonts became available and made lithographic reproduction of manuscripts more feasible. In the present day, hieroglyphics can be rendered in desktop publishing software and this, combined with digital print technology, means that the costs of publishing a Book of the Dead may be considerably reduced. However, a very large amount of the source material in museums around the world remains unpublished.[71] In 2023, the Ministry of Antiquities announced the finding of sections of the Book of the Dead on a 16-meter papyrus in a coffin near the Step Pyramid of Djoser.[72] This scroll is now known as the Waziri Papyrus I, after Mostafa Waziri. Chronology

See also

ReferencesCitations

Works cited

Further reading

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Book of the Dead. Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Book of the Dead.

|