|

Butchulla

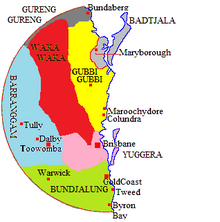

The Butchulla, also written Butchella, Badjala, Badjula, Badjela, Bajellah, Badtjala and Budjilla, are an Aboriginal Australian people of K'gari, Queensland, and a small area of the nearby mainland of southern Queensland. LanguageThe Butchulla spoke Badjala, considered to have been a dialect of Gubbi Gubbi,[1] like other K'gari dialects.[2] Their ethnonym, variously transcribed as Butchulla, Batjala, Badjala and other variations, has been etymologised as signifying "sea folk", though Norman Tindale suggested that the word better lends itself to an analysis as combining ba ("no") with the suffix tjala, meaning "tongue".[3] In the 1800s there were reported to be 19 groups that lived on the island permanently, with the island split into three sections. The people in the northern part of the island (Ngulungbara) were a separate group from the other two and did not want to be associated with the Badjala people, when they were pressed into the same mission. The people of the lower part of the island (Dulingbara) also moved along the coast line to Noosa area. All three groups – Ngulungbara, Butchulla and Dulingbarra – seem to have spoken dialect variations of Gubbi Gubbi.[4] The Batjala language was spoken in the Hervey Bay region inland towards Maryborough and Mt Bauple, as well as along the Fraser Coast, including K'gari.[5] Country Butchulla lands were concentrated in the centre of the island of K'gari (a name which refers to the former Fraser Island as well as surrounding waters and parts of the nearby mainland[6]), and extended over 1,700 square miles (4,400 km2) to the coastal mainland (Cooloola[7]) south of Noosa.[3] The Butchulla route to the mainland ran through the lower waters of the Tinana Creek and their territory ran north to Pialba in Hervey Bay, and their borders to the west ran parallel to the upper Mary River.[3][8] To the southwest of their mainland territory were the Gubbi Gubbi,[8] with the territories of the Butchulla, Gubbi Gubbi and Dulingbara sometimes marked as meeting at Mount Bauple.[9] Some two decades after the arrival of Europeans, the original population of K'gari was estimated to be in the range of approximately 2,000 people, according to Archibald Meston,[10] a figure which, if true, would mean that the ecology was sufficiently rich in food resources to sustain one of the densest pre-contact populations of the Australian continent, paralleling only the Kaiadilt of Bentinck Island.[3] Social organisationK'gari's abundance of fish resources made it rank, with the Kaiadilt homeland of Bentinck Island, as one of the two most densely populated areas on the Australian continent.[11] The peoples of K'gari were generally classified into three distinct units: Ngulungbara, Butchulla and Dulingbara, each composed of several clan groups, and, altogether, making up 19 subgroups.[12] The Ngulungbara were in the northern sector, the Butchulla in the strict sense occupied the middle of the island, while the Dulingbara lay south. The Dulingbara and Ngulungbara claimed a separate, distinct tribal status.[b] European contactArchaeological and radiocarbon studies of a lead weight containing fragments of Loisels pumice unearthed on the island identify the lead component as of French provenance, and the pumice suggests that the object may have arrived on the beach between 1410 and 1630 C.E., the first date prior to Ferdinand Magellan's circumnavigation of the world.[13] Matthew Flinders was the first white person to land on the island, at Bool Creek on Sandy Cape in July 1802 and made short contact with the Ngulungbara horde.[10] In 1836 survivors of the shipwreck of a brig, the Stirling Castle managed to make their way south and landed up on the island. Eliza Fraser, the late captain's wife, managed to survive among the local islanders for several weeks. The island began to be occupied by white people in 1849. At that time, the Indigenous population of the 19 clans was estimated to be around 2,000. Within three decades (1879), their numbers had dropped to around 300–400, a collapse attributed by an informant of the then Chief Commissioner of Brisbane to shootings by the Australian native police, and the effects of venereal disease and alcohol introduced by white people.[14] The main remnant of the Butchella people, regarded as hostile to settlers, was transferred to Yarrabah sometime around 1902,[3] and to Barambah station.[citation needed] Native titleIn 2014 an Australian Federal Court granted Native title rights to K'gari to the Butchulla people.[15] Alternative names

Source: Tindale 1974, p. 165 Notes

Citations

Sources

|