|

Cacerolazo

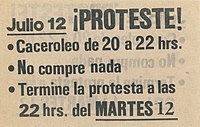

In Spanish, a cacerolazo (Spanish pronunciation: [kaθeɾoˈlaθo] or [kaseɾoˈlaso]) or cacerolada ([kaθeɾoˈlaða]); also in Catalan a cassolada (Catalan pronunciation: [kə.suˈɫa.ðə] or [kə.soˈɫa.ðə]) is a form of popular protest which consists of a group of people making noise by banging pots, pans, and other utensils in order to call for attention. The first documented protests of this style occurred in France in the 1830s, at the beginning of the July Monarchy, by opponents of the regime of Louis Philippe I of France. According to the historian Emmanuel Fureix, the protesters took from the tradition of the charivari the use of noise to express disapproval, and beat saucepans to make noise against government politicians. This way of showing discontent became popular in 1832, taking place mainly at night and sometimes with the participation of thousands of people. More than a century later, in 1961, "the nights of the pots" were held in Algeria, in the framework of the Algerian War of Independence. They were thunderous displays of noise in cities of the territory, carried out with homemade pots, whistles, horns and the cry of "French Algeria". In the following decades, this type of protest was limited almost exclusively to South America, with Chile being the first country in the region to register them. Subsequently, it has also been seen in Spain—where it is called cacerolada ([kaθeɾoˈlaða]) or, in Catalan, cassolada)—and in other countries, like the Netherlands, where it's called lawaaidemonstratie (noise protest). The word comes from Spanish cacerola, which means "stew pot". The derivative suffixes -azo and -ada denote a hitting (punching or striking) action.[1] This type of demonstration started in 1971 in Chile, against the shortages of food during the administration of Salvador Allende.[2][3] When this manner of protest was practiced in Canada,[4] in English it was referred to by most media as "casseroles" rather than the Spanish term cacerolazo. In the Philippines, the unrelated term "noise barrage" is used for this and a wider set of protest-oriented noisemaking. During the Martial Law period, a noise barrage was held on the eve of the 1978 elections for the Interim Batasang Pambansa, to protest against the authoritarian government of President Ferdinand Marcos. Per countryArgentina2000s

One of the largest cacerolazos occurred in Argentina during 2001, consisting largely of protests and demonstrations by middle-class people who had seen their savings trapped in the so-called corralito (a set of restrictive economic measures that effectively froze all bank accounts, initially as a short-term fix for the massive draining of bank deposits). The corralito meant that many people who needed a large amount of cash immediately, or who simply lived off the interests from their deposits, suddenly found their savings unavailable. As court appeals were slow and ineffective, people resorted to protest in the streets. As the Argentine peso quickly devalued and foreign currency fled the country, the government decreed a forced conversion of dollar-denominated accounts into pesos at an arbitrary exchange rate of 1.4 pesos per dollar. At this point the unavailability of cash for people trapped in the corralito compounded with the continuous loss of value of their savings, and the unresponsiveness of the appeal authorities (minor courts and the Supreme Court itself) further angered the protesters.  The first cacerolazos were spontaneous and non-partisan. While in Argentina most demonstrations against government measures are customarily organized by labour union activists and low-level political recruiters among the lower classes, and often featuring an assortment of large banners, drums and pyrotechnic devices, cacerolazos were composed mostly of spontaneously gathered middle-class workers, who otherwise had little to no involvement in grassroots political actions of any kind. The cacerolazo later led to organised street protests, often of a violent nature, directed against the government and banks. Facades were spray-painted, windows broken, entrances blocked by tire fires and some building occupied by force. In order to avoid further unrest, especially after the December 2001 riots, the government decided against a more forceful approach against the cacerolazos unless absolutely necessary and restricted police presence to barricades in critical spots. Isolated cacerolazos also featured during the apagón ("blackout") of September 24, 2002, to protest against increases in public service fees requested by the providers. As the financial and macroeconomic conditions became more stable, the government loosened the restrictions on the withdrawal of deposits, and the cacerolazos ceased. On March 25, 2008, a group led by Luis D'Elía, a supporter of the Kirchner administration, and a cacerolazo violently faced each other during the demonstrations for and against the export tax policy of Cristina Kirchner's government.[5][6][7][8] 2010s On May 31, 2012, a nationwide cacerolazo took place with a massive following of approximately ten thousand people in the capital alone. The march was organised on the internet and was in protest of the Kirchnerite government, specifically against the introduction of controls on the foreign currency exchange market by Cristina Kirchner's government, rampant crime rates, a sense of disruption and infringement of civil rights due to increasingly interventionist policies by the AFIP tax agency, including a fiscal reform in Buenos Aires province that would more than triple the land property tax, income tax rates unadjusted according to real inflation, persevering high inflation, a devalued currency, the inability to save money and alleged corruption charges against government and policymakers.[9][10][11] These protests were followed by further cacerolazos on May 31 and June 1.[9][10][11] On June 7, there was a cacerolazo with a concentration of around a thousand people in Plaza de Mayo and in Buenos Aires's avenues intersections of upper-class neighbourhoods.[12] The following week, June 14, another gathering in Plaza de Mayo was attended by a just a few hundred.[13] On September 13, thousands of Argentines marched in the largest protests since 2008 against the government of President Cristina Fernandez, who, according to an opinion poll by Management & Fit,[14] had lost popularity since her landslide re-election the previous year (this point was contested by the research company Equis, whose CEO Artemio López stated that the popularity indexes remained stable[15]). The event raised a noticeable polemic, as news coverage from most government-aligned newspapers and TV broadcasters was reduced to a minimum, and government officials' claim regarding that the cacerolazo only represented a small and minority portion of the population.[16] Another protest was made on November 8, commonly known as 8N amongst the country, principally in the Obelisco and the Plaza de Mayo, and around the world in the major cities of Spain, the US, Canada, Brazil, France, the UK and bordering countries. The latter was also called within Facebook and Twitter, though in contrast to the one on September 13, which had over 50,000 people, 250,000 were present at the 8N. The main complaints were, again the February rail accident victims, inflation and the rejection of the possible "re-re-election" of Kirchner, but also insecurity and the Ley de Medios. Again, Todo Noticias dedicated to transmit it completely, while other media supporting the president, such as América TV and C5N, in which a reporter was knocked down [17] were also present. The president of the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina, Guillermo Borger, described the presence of swastikas during the protest march held by anti-government sectors in the Plaza de Mayo and other parts of the country as "reprehensible and abominable". "There is nothing that can justify the presence of these symbols", which recalled "the aberrant moment in the history of mankind," the official told the agency that plays Jewish News (AJN).[18] BrazilCacerolazos are known in Brazil as panelaços (from the Portuguese word for pot panela). Panelaços were first popularized in protests against then-President Dilma Rousseff in 2015, when Brazilians would bang pots from the windows and balconies of their apartments during Rousseff's televised speeches.[19] The popularity of panelaços resurfaced in 2020, amid the global pandemic of COVID-19, to protest President Jair Bolsonaro. Motives for the protests have included Bolsonaro's downplaying of the pandemic crisis and his dismissal of Justice minister Sergio Moro.[20][21] Canada In 2012 in Québec citizens were using cacerolazo after the adoption on 18 May of Bill 78, an act which restricts rights to assemble after peaceful protests were met with police violence in Montreal and Victoriaville. Bill 78, aimed at restoring access to education for those students who disagreed with the general strike and at protecting businesses and citizens from any violence that might occur as a result of a protest, has been criticized by the United Nations, the Quebec Bar Association, Amnesty International, and others. Court challenges against the bill are underway. A large number of "casseroles" or "pots and pans demonstrations" were held in towns and cities across the province, with the largest ones being primarily concentrated in Montreal's various neighbourhoods.[22][23] More protests outside the Province of Quebec (over 66 other Canadian locations) were held in solidarity with the student protesters, including cities and towns such as Vancouver, Calgary,[24] Saskatoon,[25] Winnipeg,[4] Hamilton,[26] Sudbury,[27] Tatamagouche,[28] and Halifax.[29] In 2004, a song named Libérez-nous des libéraux (Liberate Us From Liberals) was written, which prophesied "Need to rush into the street / like a spring flood / shattering our discontent / a debacle of pans / enough talking, make noise / a charivari to topple the party / as in Argentine, in Bolivia".[30] On June 15, 2012, when the same band played a gig at Francofolies, they asked everybody to bring their pans and spoons.[31] Chile Cacerolazos began in Chile in 1971 in protest of food shortages[32] during the Salvador Allende administration, with the empty pots symbolising the difficulties of households in obtaining enough food to feed families. They were initially led and driven by women, representing household economic stresses as distinct from the industrial protests representing business-related financial stresses. By 1973 they had become commonplace as protests against the administration intensified amid increasing shortages. After Augusto Pinochet seized power in 1973 cacerolazos disappeared for a time until the economic crisis of 1982-83 set in. Thereafter cacerolazos continued up until the Pinochet regime lost a plebiscite in 1988 that put him out of office two years later. Cacerolazos were organized in 2011 for two different reasons. On May 15 there was pot-banging in several cities in protest of the HidroAysén dam project.[33] Then in August there were two cacerolazos across the country in support of student protests, the first on August 4[34] and a second one on August 8.[35] On November 18 there was another cacerolazo because of the murder of a Mapuche farmer, Camilo Catrillanca, at the hands of Chile's anti-terrorist police unit "Comando Jungla" (Jungle Command) in the community of Temucuicui, in Chile's Araucania Region on November 14. He was working with his tractor near his home when he was shot in the back of his head; 5 other people resulted injured.[36][37] After October 18, 2019, cacerolazos were organized during the protests originally motivated by the Santiago Subway company increase in the price of the metro ticket (see 2019 Chilean protests). EcuadorA cacerolazo in Quito, Ecuador occurred on October 12 during the 2019 Ecuadorian protests in spite of (or because of) a government-mandated curfew. Both sides claimed that the cacerolazo had been organized by them to support their cause.[citation needed] The following day, indigenous peoples met with the Moreno government for a dialogue and the protests were resolved. FranceUnder the July monarchy, republican opponents to the new regime used this practice during their demonstrations. It reached in 1832 a national dimension, during which a hundred of these events were combined.[38] In 1961, this phenomenon reappears as a form of popular protest by the pieds-noirs in favor of maintaining French Algeria, against the Gaullist policy of self-determination and independence of the country. During nightly concerts, often organized on the initiative of the Organisation armée secrète, the inhabitants, mounted on the terraces, or from their balconies, chanted on pans in telegraphic style three short and two long symbols of "Al-gé-rie fran-çaise" (French Algeria).[39] In 2016, among the strikes and demonstrations against the El Khomri law, "Casseroles debout" (in reference to the social movement Nuit debout), are organized in 350 cities "from 7:30 p.m." for "exchanges, debates, aperitif".[40] These casseroles gradually gained momentum in 2023 during the 2023 French pension reform unrest. On Monday, April 3, 2023, 2000 people participate in such demonstration in Nantes. A national call to participate in casseroles was triggered by some associations in response to Emmanuel Macron's televised address after the promulgation of the law. More than 370 casserole protests took place according to the association Attac France.[41] IcelandThe protests following the financial crisis that started in 2008 are sometimes called The Kitchenware Revolution, because people took to the streets banging on pots and pans and other household utensils.[citation needed] IndiaOn March 22, 2020, at 5 PM IST for 5 minutes, Indians across the country used sauce pans and other kitchen utensils to make noise to show their appreciation and support to all the service men and women on the front line for the fight against coronavirus. More than a billion people in India voluntarily stayed indoors for 14 hours to try to combat the coronavirus pandemic. Prime Minister Narendra Modi told citizens that it would be a test in order to assess the country's ability to fight the virus and to come out on their balconies at 5 pm and make noise with bells or kitchen utilities as a show of support.[42] LebanonIn 2019, nationwide protests erupted in Lebanon on October 17 following years of political corruption and economic instability. Protesters in Saida, Tripoli, and Beirut, as well as many other cities and regions in the country, took to banging on pots and kitchen utensils from their balconies. This technique was also integrated into street protests.[43] Online calls were circulated to repeat this form of demonstration every day at 8:00 P.M. Puerto RicoDuring the summer of 2019, Puerto Rico endured a political and constitutional crisis caused by indictments on corruption charges of cabinet officials, and revelations of a Telegram chat group led by the sitting governor, Ricardo Rosselló. This chat group included government officials and lobbyists, and revealed that the governor and other participants made homophobic, misogynistic, and other prejudicial comments which also mocked the dead and other victims of Hurricane Maria, as well as threatened and defamed political opponents, the press, and others who they considered not to be allied with their government. The country erupted in protests, and for 15 straight days, all sectors of Puerto Rican society took to the streets in peaceful protests. Cacerolazos were a key expression of public rage and took place in front of the executive mansion, in public plazas across the islands, from the balconies of condominiums, the patios of homes, and other public settings. The governor eventually resigned as a result of these protests, which led to a constitutional crisis of succession. In less than a week Puerto Rico had three different occupants in the governor's office, and to date the crisis has not yet been fully resolved.[citation needed] MexicoIn 2006, during the Oaxaca protests that saw thousands occupy their city following the police repression of teachers' strike, 5000 women marchers banged pots and pans with spoons and meat tenderizers.[44] Their march took them through the city squares and to outside the state-run television station channel 9. The women demanded a one-hour slot to report on the people's story of what was happening in Oaxaca; a story that was censored and skewed by government propaganda against the protesters. When the station refused the women, still carrying their pots and pans, entered the building and took over the station. They carried out live broadcasts of the people's struggles.[45] MoroccoIn 2017 and 2018, Hirak Rif or Rif Movement activists in the Rif region used cacerolazo to protest against Morocco's politics in the Rif region.[citation needed] MyanmarFollowing the coup d'état in 2021, most people living in Myanmar banged on pots and pans around 8 at night to express their opposition to the military takeover.[46] It is believed to be a traditional method of warding off evil spirits.[47] SpainPandorga, mojingas, rondas de mozos, matracas or simply cencerradas were the terms to refer in Spain to mocking rituals in which folks took part in using kitchenware and/or similar utensils. It is however difficult to trace a historical continuity between cencerradas and modern day caceroladas.[48] A majority of Spaniards were against the Iraq War[49] and provoked during 2003 cacerolazo-fashioned protests against the government decision to support it.[50] People protested from their homes turning lights on and off, making noise with whistles and klaxons and hitting stew pots. In Huesca lamp posts of 16 streets were turned off in protest for 15 minutes. During the Catalan general strike in October 2017, Catalans protested the response of King Felipe VI with cacerolazo.[51] A widespread cacerolada from the balconies of cities across Spain was organised on 18 March 2020 counterprogramming the TV discourse of Felipe VI on the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, intending to force king emeritus Juan Carlos to donate to public healthcare the €100M he had allegedly obtained through kickbacks from Saudi Arabia.[52][53] A number of caceroladas have been called throughout the country in the months of April and May 2020 to protest against the Government management of the Coronavirus crisis.[54][55] TurkeyDuring the 2013 protests in Turkey when late at night after May 31 people in central Istanbul were forced to go to their homes due to the high amounts of tear gas, they continued protesting from their homes by banging pots and pans. About half past one the entire city started to reverberate.[56] This also functioned to create awareness of the situation since the self-censorship of media prevented people from being informed about the scale of the protests. After the first day, this form of protest continued, starting every evening at 9pm, and lasting a few minutes. Venezuela  After the 2013 presidential election on 15 April millions of Capriles supporters banged their pots and pans in the streets and from their windows after Capriles refused to accept the results, asked for a recount, and told the whole country to protest during a power cut of three hours in some places nationwide. The next day, Capriles supporters continued the cacerolazo, asking for a recount. Similar concentrations were observed all over the world, particularly in South and Central Florida, where a lot of Venezuelan citizens reside, most of them Capriles sympathizers. It was none other than Capriles himself who called for a "cacerolazo" to denounce the election results, after the National Electoral Council declared Nicolás Maduro of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela the official winner in the snap presidential elections held the previous day.[57] Several cacerolazos took place during the 2014 Venezuelan protests. On August, the MUD reactivated protests by calling on supporters to hold a nationwide cacerolazo at 8:00 pm local time against the new proposed fingerprint rationing system.[58][59] The cacerolazo took place in several states.[60] After marches on a national level to Caracas to demand a recall referendum on 2016, opposition leader Chúo Torrealba called for a cacerolazo.[61] While Maduro was inaugurating houses of the Gran Misión Barrio Nuevo, Barrio Tricolor, people from Villa Rosa, Nueva Esparta state, received him with a cacerolazo.[62] At least 30 persons were detained by the Bolivarian Intelligence Service (SEBIN) after the cacerolazo in Villa Rosa.[63] During the 2017 Venezuelan protests, many cacerolazos also took place. On 15 June cacerolazos were held in Caracas, where the banging pots were heard throughout the capital city.[64] After the results of the 2018 presidential election were read, where Nicolás Maduro was declared re-elected, many Venezuelans throughout Caracas started a cacerolazo protest against Maduro, with some beginning to barricade streets.[65] During the Venezuelan presidential crisis, on 21 January 2019, a group of National Guardsmen rose up in Cotiza, in Caracas.[66] Neighbors nearby started a cacerolazo and a demonstration in support of the officers. Government forces repressed the protestors with tear gas and the uprising was quelled quickly.[67] People in Caracas also held cacerolazos during the 2019 blackouts to protest against the outages.[68] When Radio Caracas Televisión (Radio Caracas Television, RCTV) was forcefully shut down by the Venezuelan government in May 2007 after their broadcast licence was not renewed, and replaced with TVes, Cacerolazo protests formed around the country to protest against the closedown of the channel, which was the longest living public channel? in Venezuela.[citation needed] Although the channel was dead on terrestrial, it started up again later in June 2007? as RCTV Internacional (RCTV International) as a pay TV channel, and lasted nearly 3 years until it was shut down again in late January 2010. RCTV had moved to cable in 2007 after the Venezuelan government of Hugo Chávez refused to renew its terrestrial license, which brought up the 2007 RCTV protests in Venezuela. In 2010, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez had taken six cable television channels off the air, including RCTV International, for breaking a law on transmitting government material. The government had urged cable services to drop channels ignoring the rules.[69] See alsoReferences

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to cacerolazo. |