|

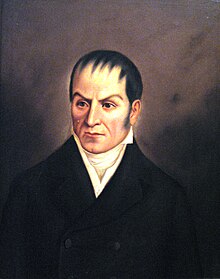

Camilo Torres Tenorio

José Camilo Clemente de Torres Tenorio (November 22, 1766 – October 5, 1816) was a Neogranadine independence leader and lawyer who also served as president of the United Provinces of New Granada. He is credited as being an early founder of the nation due to his role in early struggles for independence from Spain.[1] Biography Torres was born in Popayán, Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1766. He was the son of Francisco Jerónimo Torres and María Teresa Tenorio. Torres studied in the Seminary of Popayán, where he met others of the leaders of the Colombian independence movement like Francisco Antonio Zea and his cousin, Francisco José de Caldas. He then moved to Santafé (now known as Bogotá), to study jurisprudence in the Colegio del Rosario, where he obtained a bachelor's degree in Canonical Law in June of 1790, and a J.D degree in 1791.[2] He decided to settle in Santafé, where he opened an attorney's office.[3] Torres married María Francisca Prieto y Ricaurte in 1802 in Bogotá. They had six children.[3] Torres was part of a generation that had witnessed the Insurrection of the Comuneros in 1781, and had experienced the independence of the United States in 1776 and the French Revolution in 1789. Antonio Nariño had translated into Spanish the "Declaration of the Rights of Man" in 1794, and had spread the influence of these ideas all throughout Latin America. This translation led to Nariño being exiled, and many of the students in the Colegio del Rosario were in turn persecuted, including Torres. With the abdication of Ferdinand VII in Spain, Torres advocated the formation of a Junta, such as were being created in Spain, in support of the abdicated king. Torres also supported the creation of the Supreme Central Junta in 1809, particularly as it was supposed to include representation from the American colonies. This representation, however, was very small and insignificant, and this led to Torres writing his famous "Memorial de agravios" (Memorial of Grievances), where he complained about the lack of equality for American Spaniards and the scarce attention that the American colonies received from the Spanish crown. Torres, however, praised the Spanish authority and expressed his desire that the colonies would not secede.[4][5]  The dissolution of the Supreme Central Junta led to the creation of local juntas in many provinces in Latin America, which consolidated the thirst for independence of the American colonies. In Santafé, a Junta was established on July 20, 1810, which demanded the creation of an open council and independence from Spain. Among the deputies of such council was Camilo Torres, and he was one of the signers in the Act of Independence of the Supreme Junta of Santafé. Torres was also involved in finding some understanding with the Spanish crown.[2] Antonio Nariño started publishing a small newspaper called La Bagatela in 1811, where he presented his centralist ideas for the government of the new country. This soon made him an antagonist of Torres, who instead supported federalist ideas that emphasized autonomy for the provinces. This conflict led to the formation of two political parties, the centralist one (the "pateadores" or kickers) represented by Nariño, and the Federalist one (or "carracos"), formed by Torres and representatives from other provinces. The federalist faction formed the United Provinces of New Granada in 1811, and Torres was appointed as President of its congress between 1812 and 1814, and then as President of the United Provinces between 1815 and 1816. During this period, Camilo Torres befriended Bolívar. The Province of Santafé had declared itself independent and adopted the name of Free and Independent State of Cundinamarca. The tensions between the centralist Cundinamarca province and the federalist United Provinces eventually led to a civil war that culminated in the surrender of the Cundinamarca province to the federalist troops commanded by Bolívar in 1814. This period of strife and chaos is called often la Patria Boba. Meanwhile, king Ferdinand VII of Spain had been restored to power and sent a large army to quell the rebellions and reconquer the lost colonies. The Spanish army, commanded by General Pablo Morillo led a violent, and successful military campaign that culminated in the capture of Santafé on May 6, 1816. Fearing Morillo's troops, Torres escaped to the small town of El Pital, near Neiva. He then tried to escape the country by boarding a ship to Argentina in the port of Buenaventura, but he was captured by the troops of Juan Sámano after the ship departed without him and others in July, 1816.[3] He was sent to Santafé, where he was executed by a firing squad for treason against the Spanish monarchy on October 5, 1816. After his death, all of his possessions were confiscated and his family was stranded in poverty. When Bolívar became president he decided to support them by donating part of his own stipend every month. Camilo Torres' face has appeared in the $2 and $50 Colombian peso banknotes. References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||