|

Classical Ottoman architecture

Classical Ottoman architecture is a period in Ottoman architecture generally including the 16th and 17th centuries. The period is most strongly associated with the works of Mimar Sinan, who was Chief Court Architect under three sultans between 1538 and 1588. The start of the period also coincided with the long reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, which is recognized as the apogee of Ottoman political and cultural development, with extensive patronage in art and architecture by the sultan, his family, and his high-ranking officials.[1] Ottoman architecture at this time was strongly influenced by Byzantine architecture, particularly the Hagia Sophia, and blended it with other influences to suit Ottoman needs.[2][3] Architects typically experimented with different combinations of conventional elements including domes, semi-domes, and arcaded porticos.[4][5] Successful architects such as Sinan demonstrated their skill through their meticulous attempts to solve problems of space, proportion, and harmony.[4] Sinan's most important works include the Şehzade Mosque, Süleymaniye Mosque, and Selimiye Mosque.[6][1][7] After Sinan's death, the classical style became less innovative and more repetitive.[4] The 17th century still produced major works such as the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, but the social and political changes of the Tulip Period eventually led to a shift towards Ottoman Baroque architecture. BackgroundMajor developments in early Ottoman architecture Early Ottoman mosques up to the early and mid 15th century were generally of three types: the single-domed mosque, the "T-plan" mosque, and the multi-domed mosque.[8] A major step towards the style of later Ottoman mosques was the Üç Şerefeli Mosque in Edirne, begun by Murad II in 1437 and finished in 1447.[9][10] The overall form of the mosque, with its central-dome prayer hall, arcaded courtyard with fountain, four minarets, and tall entrance portals, foreshadowed the features of later Ottoman mosque architecture.[9] Scholar Doğan Kuban describes it as the "last stage in Early Ottoman architecture", while the central dome plan and the "modular" character of its design signaled the direction of future Ottoman architecture in Istanbul.[11] He also notes that the mosque, which is built in cut stone and makes use of alternating bands of coloured stone for some of its decorative effects, marks the decline of the use of alternating brick and stone construction seen in earlier Ottoman buildings.[12] Ottoman sultans traditionally built monumental mosques and religious complexes in their name. After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, Sultan Mehmed II built the Fatih Mosque between 1463 and 1470, which is dedicated to his name. It was part of a very large külliye (religious and charitable complex) which also included a tabhane (guesthouse for travelers), an imaret (soup kitchen), a darüşşifa (hospital), a caravanserai (hostel for traveling merchants), a mektep (primary school), a library, a hammam (bathhouse), shops, a cemetery with the founder's mausoleum, and eight madrasas along with their annexes.[13][14] Unfortunately, much of the mosque was destroyed by an earthquake in 1766, causing it to be largely rebuilt by Mustafa III in a significantly altered form shortly afterwards. The original design of the mosque, drawing on the ideas established by the earlier Üç Şerefeli Mosque, consisted of a rectangular courtyard with a surrounding gallery leading to a domed prayer hall. The prayer hall consisted of a large central dome with a semi-dome behind it and flanked by a row of three smaller domes on either side.[15] The design reflected the influence of the Byzantine-built Hagia Sophia combined with the Ottoman imperial mosque tradition that had evolved in Bursa and Edirne.[15][16][17]  The Bayezid II Mosque in Istanbul, built between 1500 and 1505, was the culmination of the period of architectural exploration in the late 15th century and was the last step towards the classical Ottoman style.[18][19] The deliberate arrangement of established Ottoman architectural elements into a strongly symmetrical design is one aspect which denotes this evolution.[19] The mosque was again part of a larger külliye complex with multiple buildings serving different functions.[20][21] The mosque structure consists of a square courtyard leading to a square prayer hall. The prayer hall is roofed by a central dome with two semi-domes in front and behind it, while two side aisles are each covered by four smaller domes. Compared to earlier mosques, this resulted in a much more sophisticated "cascade of domes" effect for the building's exterior profile, likely reflecting influences from the Hagia Sophia and the Fatih Mosque.[22] Context of the Ottoman classical periodThe classical period of Ottoman architecture was to a large degree a development of the prior approaches as they evolved over the 15th and early 16th centuries and the start of the classical period is strongly associated with the works of Mimar Sinan.[2][3] During this period the bureaucracy of the Ottoman state, whose foundations were laid in Istanbul by Mehmet II, became increasingly elaborate and the profession of the architect became further institutionalized.[1] The Ottoman administration included a "palace department of buildings" or "corps of royal architects" (khāṣṣa mi'mārları).[22][23] The first documented references to this department date from the reign of Bayezid II (r. 1481–1512).[23] It grew from 13 architects in 1525 to 39 architects by 1604.[22] Many of the architects and bureaucrats were recruited from the Christian population of the empire through the devshirme system.[22] The long reign of Suleiman the Magnificent is also recognized as the apogee of Ottoman political and cultural development, with extensive patronage in art and architecture by the sultan, his family, and his high-ranking officials.[1] The master architect of the classical period, Mimar Sinan, served as the chief court architect (mimarbaşi) from 1538 until his death in 1588.[24] Sinan credited himself with the design of over 300 buildings,[25] though another estimate of his works puts it at nearly 500.[26] He is credited with designing buildings as far as Buda (present-day Budapest) and Mecca.[27] Sinan was probably not present to directly supervise projects far from the capital, so in these cases his designs were most likely executed by his assistants or by local architects.[28][29] This also demonstrates the ability of the central Ottoman state to commission and plan building projects across its vast territory at the time, a practice that also helped to establish Ottoman sovereignty in these provinces through the construction of monuments in a visibly Ottoman style.[28] Architects in the capital were able to draw plans and delegate them to other architects who carried them out locally, while the imperial administration developed a set of standards for planning and construction and was able to coordinate the procurement and transportation of the necessary materials.[28] General characteristicsIn this period Ottoman architecture, especially under the work and influence of Sinan, saw a new unification and harmonization of the various architectural elements and influences that Ottoman architecture had previously absorbed but which had not yet been harmonized into a collective whole.[2] Taking heavily from the Byzantine tradition, and in particular the influence of the Hagia Sophia, classical Ottoman architecture was, as before, ultimately a syncretic blend of numerous influences and adaptations for Ottoman needs.[2][3] Ottoman architecture used a limited set of general forms – such as domes, semi-domes, and arcaded porticos – which were repeated in every structure and could be combined in a limited number of ways.[4] Doğan Kuban describes this as the "modular" aspect of Ottoman architecture.[5] The ingenuity of successful architects such as Sinan lay in the careful and calculated attempts to solve problems of space, proportion, and harmony.[4] Sinan himself continuously experimented with different spatial arrangements for his buildings throughout his career, seldom using the same design more than once.[5] After Sinan, his less talented successors showed less creativity and the later classical style became stale and repetitive by comparison with earlier periods.[4] In what may be the most emblematic of the structures of this period, the classical mosques designed by Sinan and those after him used a dome-based structure, similar to that of Hagia Sophia, but among other things changed the proportions, opened the interior of the structure and freed it from the colonnades and other structural elements that broke up the inside of Hagia Sophia and other Byzantine churches, and added more light, with greater emphasis on the use of lighting and shadow with a huge volume of windows.[2][3] These developments were themselves both a mixture of influence from Hagia Sophia and similar Byzantine structures, as well as the result of the developments of Ottoman architecture from 1400 on, which, in the words of Godfrey Goodwin, had already "achieved that poetic interplay of shaded and sunlit interiors which pleased Le Corbusier."[2] The legacy of the Hagia Sophia and early Ottoman mosques is also reflected by the continuing use of semi-domes alongside the main dome and the use of pendentives to accomplish the transition from the dome to the square or polygonal space below.[30] In the Ottoman style canonized by Sinan, the design of monumental Ottoman buildings was conceptualized with the central dome above as its starting point, rather than the floor plan being conceived first and the roofing system after.[31] In particular, the core of the design was the domed baldaquin, which is to say the dome and its basic structural support system: a set of pillars or buttresses in a square, hexagonal, or octagonal configuration – involving four, six, or eight pillars, respectively.[32] Whereas early Ottoman buildings relied on brick and rubble masonry for construction, in the 16th century it was standard for walls to be made with a rubble core and faced with cut stone, particularly cut limestone. Some buildings were still constructed with the older technique of alternating layers of brick with layers of stone, but this was more common for auxiliary structures rather than major monuments. Domes and vaults continued to be built with brick, which was lighter than stone and thus more suited for this purpose, and then typically covered with lead on the outside.[33] By the 16th century, the empire contained many old disused Byzantine churches and it was common practice to reuse marble columns taken from these sites, which provided much of the marble for new constructions in this period. Fresh marble was also quarried around Marmara.[33] Occasionally, when there was a shortage of marble or in situations where marble was risky for certain structural elements, "fake marble" was used: usually brick covered with plaster painted to look like marble.[33] The classical period is also notable for the development of Iznik tile decoration in Ottoman monuments, with the artistic peak of this medium beginning in the second half of the 16th century.[34][35] Classical architecture under SinanEarliest buildings of Suleiman's reignBetween the reigns of Bayezid II and Suleiman I, the reign of Selim I saw relatively little building activity. The Yavuz Selim Mosque complex in Istanbul, dedicated to Selim and containing his tomb, was completed after his death by Suleiman in 1522. It was quite possibly founded by Suleiman too, though the exact foundation date is not known.[36][22] The mosque is modelled on the Mosque of Bayezid II in Edirne, consisting of one large single-domed chamber.[37] The mosque is sometimes attributed to Sinan but it was not designed by him and the architect in charge is not known.[37][38][39] The Tomb of Selim I, located behind the mosque, is the culmination of domed octagonal tombs which developed in earlier Ottoman architecture.[40] The tomb is entered via a small porch and on either side of the door are two panels of early cuerda seca tiles characteristic of early 16th century Ottoman tilework. The architect of the tomb is named in an inscription as Acem Alisi.[40] Other notable architectural complexes before Sinan's architect career, at the end of Selim II's reign or in Suleiman's early reign, are the Hafsa Sultan or Sultaniye Mosque in Manisa (circa 1522), the Fatih Pasha Mosque in Diyarbakir (completed in 1520 or 1523), and the Çoban Mustafa Pasha Complex in Gebze (1523–1524).[41][42] Prior to being appointed chief court architect, Sinan was a military engineer who assisted the army on campaigns. His first major non-military project was the Hüsrev Pasha Mosque complex in Aleppo, one of the first major Ottoman monuments in that city. Its mosque and madrasa were completed in 1536–1537, though the completion of the overall complex is dated by an inscription to 1545, by which point Sinan had already moved on to Istanbul.[43] (The complex has since been severely damaged during the Syrian civil war.[44]) After his appointment to chief court architect in 1538, Sinan's first commission for Suleiman's family was the Haseki Hürrem Complex in Istanbul, dated to 1538–1539 and commissioned by Haseki Hürrem Sultan, Suleiman's wife.[22][14] He also built the Tomb of Hayrettin Barbaros in the Beşiktaş neighbourhood in 1541.[45][46]

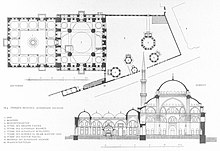

The Şehzade Mosque Sinan's first major commission was the Şehzade Mosque complex, which Suleiman dedicated to Şehzade Mehmed, his son who died in 1543.[46] The mosque complex was built between 1545 and 1548.[22] Like all imperial külliyes, it included multiple buildings, of which the mosque was the most prominent element. The mosque has a rectangular floor plan divided into two equal squares, with one square occupied by the courtyard and the other occupied by the prayer hall. Two minarets stand on either side at the junction of these two squares.[22] The prayer hall consists of a central dome surrounded by semi-domes on four sides, with smaller domes occupying the corners. Smaller semi-domes also fill the space between the corner domes and the main semi-domes. This design represents the culmination of the previous domed and semi-domed buildings in Ottoman architecture, bringing complete symmetry to the dome layout.[47] An early version of this design, on a smaller scale, had been used before Sinan as early as 1520 or 1523 in the Fatih Pasha Mosque in Diyarbakir.[48][49] While a cross-like layout had symbolic meaning in Christian architecture, in Ottoman architecture this was purely focused on heightening and emphasizing the central dome.[50] Sinan's early innovations are also evident in the way he organized the structural supports of the dome. Instead of having the dome rest on thick walls all around it (as was previously common), he concentrated the load-bearing supports into a limited number of buttresses along the outer walls of the mosque and in four pillars inside the mosque itself at the corners of the dome. This allowed for the walls in between the buttresses to be thinner, which in turn allowed for more windows to bring in more light.[51] Sinan also moved the outer walls inward, near the inner edge of the buttresses, so that the latter were less visible inside the mosque.[51] On the outside, he added domed porticos along the lateral façades of the building which further obscured the buttresses and gave the exterior a greater sense of monumentality.[51][52] Even the four pillars inside the mosque were given irregular shapes to give them a less heavy-handed appearance.[53] The basic design of the Şehzade Mosque, with its symmetrical dome and four semi-dome layout, proved popular with later architects and was repeated in classical Ottoman mosques after Sinan (e.g. the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque, the New Mosque at Eminönü, and the 18th-century reconstruction of the Fatih Mosque).[54][55] It is even found in the 19th-century Muhammad Ali Mosque in Cairo.[56][57] Despite this legacy and the symmetry of its design, Sinan considered the Sehzade Mosque his "apprentice" work and was not satisfied with it.[22][58][59] During the rest of his career he did not repeat its layout in any of his other works. He instead experimented with other designs that seemed to aim for a completely unified interior space and for ways to emphasize the visitor's perception of the main dome upon entering a mosque. One of the results of this logic was that any space that did not belong to the central domed space was reduced to a minimum, subordinate role, if not altogether absent.[60] The other buildings of the Şehzade Mosque complex include a madrasa, a tabhane, a caravanserai, an imaret, a cemetery with several mausoleums (of varying dates), and a small mektep.[61] The tomb of Şehzade Mehmed, originally the only mausoleum in the cemetery, is among the most beautiful tombs designed by Sinan.[62][63] Its design is similar to that of Selim I's tomb, with octagonal form and an entrance porch, but the decoration is more luxurious. On the exterior, the marble covering is enhanced with breccia and terracotta, the arches of the windows are made with alternating courses of red and white marble, the dome is fluted, and the octagonal walls are crowned with a carved stone frieze of lace-like palmettes. The interior walls of the tomb are entirely covered in extravagant cuerda seca tiles of predominantly green and yellow colours on a dark blue ground, featuring arabesque motifs and inscriptions. The stained glass windows are also among the best examples of their kind in Ottoman architecture.[64][63][65]

Other early works of SinanAround the same time as the Şehzade Mosque construction Sinan also built the Mihrimah Sultan Mosque (also known as the Iskele Mosque) for one of Suleiman's daughters, Mihrimah Sultan. It was completed in 1547–1548 and is located in Üsküdar, across the Bosphorus.[66][67] It is notable for its wide "double porch", with an inner portico surrounded by an outer portico at the end of a sloped roof. This feature proved popular for certain patrons and was repeated by Sinan in several other mosques.[68] One example is the Rüstem Pasha Mosque in Tekirdağ (1552–1553).[69] Another example is the Sulaymaniyya Takiyya in Damascus, the western part of which (including a mosque and a Sufi convent) was built in 1554–1559.[70][71][72][73] The Sulaymaniyya complex in Damascus is also an important example of a Sinan-designed mosque far from Istanbul, and has local Syrian influences such as the use of ablaq masonry, reused in part from an earlier Mamluk palace.[71][74] Sinan did not visit Damascus for the project – though he had been there previously with Sultan Selim's army – and the architect in charge of construction work was Mimar Todoros, who most likely used local masons and craftsmen.[75] As the site was located outside the old city walls it had plenty of open space, which allowed Sinan to design a complex with greater symmetry than most of the complexes he designed in urban Istanbul.[75] In addition to the western part of the complex completed in 1558–1559, a madrasa (the Salimiyya Madrasa) was added on its eastern side later, completed in 1566–1567.[a][77] The Damascus complex is roughly contemporary with the other constructions and renovations that Suleyman ordered further south at the holy sites of Jerusalem, Medina, and Mecca, in which Sinan was generally not involved.[78] This included the renovation of the Dome of the Rock, which began in 1545–46 and provided it with its now-famous tile decoration, and the renovation of the Kaaba in 1551–1552.[71][79] Sinan did, however, design a new charitable complex in Jerusalem for Haseki Hürrem Sultan, built around 1550–1557 and identified as the Takkiya al-Khassaki Sultan (roughly, 'Sufi convent of Haseki Sultan'). Due to the restricted space, the use of local craftsmen, and its incorporation of the earlier Mamluk-era Palace of Lady Tunshuq, the complex had little resemblance to the classical Ottoman style. Parts of the complex, including a madrasa and a mosque, are no longer extant today, but the Haseki Sultan Imaret (hospice or soup kitchen) has been preserved.[80] Sinan also designed two Sufi hospices commissioned by Hürrem Sultan in Medina and Mecca, which were completed by 1552 but are no longer extant.[81] These types of hospices and convents, known locally as a takkiya in Arabic or tekke in Turkish, catered to Sufi brotherhoods and were a new type of institution that the Ottomans introduced to these regions.[79] For Rüstem Pasha, Suleiman's grand vizier and son-in-law, Sinan also built the Rüstem Pasha Madrasa in Istanbul (1550), with an octagonal floor plan, and several caravanserais including the Rüstem Pasha Han in Galata (1550), the Rüstem Pasha Han in Ereğli (1552), the Rüstem Pasha Han in Edirne (1554), and the Taş Han in Erzurum (between 1544 and 1561).[82][83][84]

Sinan was also in charge of civil engineering works for Istanbul. One of his most important civil works, ordered by Suleiman, was upgrading the water supply system of the city, which he carried out between 1554 and 1564.[85][86] For this work he built or rebuilt several impressive aqueducts in the Belgrad Forest, expanding on the older Byzantine water supply system.[86] These include the Bent Aqueduct (Eğrikemer), the Long Aqueduct (Uzunkemer), the Mağlova Aqueduct (also known as Justinian's Aqueduct), and the Güzelce ("Beautiful") Aqueduct.[85] Doğan Kuban praises the Mağlova Aqueduct as one of Sinan's best creations.[86] Sinan also built bridges, such as the Büyükçesme Bridge outside Istanbul, completed in 1564.[86] Inside the city he built the Haseki Hürrem Hamam near Hagia Sophia in 1556–1557, one of the most famous hammams he designed, which includes two equally-sized sections for men and women.[87][88][89]

The Süleymaniye complex In 1550 Sinan began construction for the Süleymaniye complex, a monumental religious and charitable complex dedicated to Suleiman. Construction finished in 1557. Following the example of the earlier Fatih complex, it consists of many buildings arranged around the main mosque in the center, on a planned site occupying the summit of a hill in Istanbul. The buildings included the mosque itself, four general madrasas, a madrasa specialized for medicine, a madrasa specialized for hadiths (darülhadis), a mektep, a darüşşifa, a caravanserai, a tabhane, an imaret, a hammam, rows of shops, and a cemetery with two mausoleums.[90][91] The site was formerly occupied by the grounds of the Old Palace (Eski Saray) built by Mehmet II, which had been damaged by fire.[90] By this point, Suleiman had also moved his own residence and the royal family to Topkapı Palace.[43] In order to adapt the hilltop site, Sinan had to begin by laying solid foundations and retaining walls to form a wide terrace. The overall layout of buildings is less rigidly symmetrical than the Fatih complex, as Sinan opted to integrate it more flexibly into the existing urban fabric.[90] Thanks to its refined architecture, its scale, its dominant position on the city skyline, and its role as a symbol of Suleiman's powerful reign, the Süleymaniye Mosque complex is one of the most important symbols of Ottoman architecture and is often considered by scholars to be the most magnificent mosque in Istanbul.[92][93][8] The mosque itself has a form similar to that of the earlier Bayezid II Mosque: a central dome preceded and followed by semi-domes, with smaller domes covering the sides. The reuse of an older mosque layout is something Sinan did not normally do. Doğan Kuban has suggested that it may have been due to a request from Suleiman.[94] In particular, the building replicates the central dome layout of the Hagia Sophia and this may be interpreted as a desire by Suleiman to emulate the structure of the Hagia Sophia, demonstrating how this ancient monument continued to hold tremendous symbolic power in Ottoman culture.[94] Nonetheless, Sinan employed innovations similar to those he used previously in the Şehzade Mosque: he concentrated the load-bearing supports into a limited number of columns and pillars, which allowed for more windows in the walls and minimized the physical separations within the interior of the prayer hall.[95][96] The exterior façades of the mosque are characterized by ground-level porticos, wide arches in which sets of windows are framed, and domes and semi-domes that progressively culminate upwards – in a roughly pyramidal fashion – to the large central dome.[95][97] The four minarets are arranged at the corners of the courtyard, like in the earlier Üç Şerefeli Mosque, but the ones at the outer corners are shorter than those at the inner corners next to the prayer hall, thus adding to the visual impression of a heightening towards the central dome.[95] Inside, Sinan kept the ornamentation very restrained, but this was also the first mosque in Istanbul to make significant use of underglaze-painted Iznik tiles in its decoration. These tiles cover the wall around the mihrab (niche symbolizing the qibla) and feature large calligraphic roundels, designed by Ahmed Karahisari, painted across multiple tiles, along with other motifs along the sides.[98] Most of the other buildings are classical Ottoman courtyard structures consisting of a rectangular courtyard surrounded by a domed peristyle portico giving access to rooms. In the madrasas, Sinan modified some details of the typical layout for functional reasons. The Salis Medrese and Rabi Medrese, located on the northeast side of the mosque where the ground slopes down towards the Golden Horn, have a "stepped" design in which the courtyard descends in three terraces connected by stairs while the domed rooms are built at progressively lower levels alongside it.[99] The cemetery contains two mausoleums designed by Sinan: that of his wife Hürrem Sultan (dated to 1558) and that of Suleiman himself (dated to 1566 but possibly finished a little later).[100] The Tomb of Hürrem Sultan has a standard form but contains excellent Iznik tiles of the period. The Tomb of Suleiman is one of the largest Ottoman mausoleums and is surrounded by a peristyle portico with a sloping eave. Its design is sometimes compared to the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and it may have been modeled on the latter.[98][101] The structure is built in high-quality stone and Sinan designed its details to make it stand out from other Ottoman mausoleums. Rich Iznik tile panels adorn the doorway and the interior of the tomb. The dome, 14 meters in diameter, is the first major example of a double-shelled dome in Sinan's architecture.[102][101]

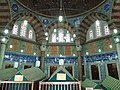

Further experimentation in mosque design After designing the Süleymaniye complex, Sinan appears to have focused on experimenting with the single-domed space.[60] In the 1550s and 1560s he experimented with an "octagonal baldaquin" design for the main dome, in which the dome rests on an octagonal drum supported by a system of eight pillars or buttresses. This can be seen in the early Hadim Ibrahim Pasha Mosque (1551) and the later Rüstem Pasha Mosque (1561), both in Istanbul.[103] The Rüstem Pasha Mosque, one of the most notable mosques in the city, is raised on top of an artificial platform whose substructure is occupied by shops and a vaulted warehouse that provided revenues for the mosque's upkeep.[104] Most famously, the mosque's exterior portico and the walls of its interior are covered in a wide array of Iznik tiles, unprecedented in Ottoman architecture.[104] Sinan usually kept decoration limited and subordinate to the overall architecture, so this exception is possibly the result of a request by the wealthy patron, grand vizier Rüstem Pasha.[34] The mosque also marks the beginning of the artistic peak of Iznik tile art from the 1560s onward.[105] Blue colours predominate in the tiles, but the important "tomato red" colour began to appear. The tiles were painted with a repertoire of motifs including tulips, hyacinths, carnations, roses, pomegranates, artichoke leaves, narcissus, and Chinese "cloud" motifs.[105][106]

In Lüleburgaz, on the road between Istanbul and Edirne, vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha founded a mosque complex named after him in 1559–1560.[107] The complex was completed in 1565–1566[107] or in 1569–1571.[43] In addition to the mosque it includes a madrasa, a caravanserai, a hammam, and a mektep (primary school), all of which is centered around a market street (arasta). The complex was designed to act as a staging post (or menzil) for travelers and traders which formed the nucleus of a new Ottoman urban center.[107] Similar complexes were built on many trade routes across the empire in this era.[108] The mosque itself is notable as Sinan's first experimentation with a "square baldaquin" structure, where the dome rests on a support system with a square layout (without the semi-domes of the Şehzade Mosque design).[109] Not long after this Mihrimah Sultan sponsored a second mosque, the Mihrimah Sultan Mosque in the Edirnekapı area of Istanbul. It was built between 1562 and 1565. Here Sinan employed a larger square baldaquin structure in which the weight of the dome is focused on four corner buttresses. The walls between the four buttresses are filled with numerous windows framed inside large arches, creating an unusually light-filled interior.[8][5][110]

For much of his career Sinan also experimented with variations of a "hexagonal baldaquin" design, a design that was uncommon in world architecture.[111] He used this model in the Sinan Pasha Mosque (1553–1555) in Beşiktaş, the Kara Ahmed Pasha Mosque (1554) in western Istanbul, the Molla Çelebi Mosque (circa 1561–1562) in Beyoğlu, the Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque (1571) in the Kadırga neighbourhood, and the Atik Valide Mosque (1583) in Üsküdar.[112] The earlier Sinan Pasha Mosque was essentially modelled on the Üç Şerefeli Mosque of Edirne, with a central dome two side domes on either side.[113] Sinan refined the hexagonal baldaquin model for the Kara Ahmet Pasha Mosque, dispensing of the side domes and replacing them with semi-domes opening off the main dome. This change allowed for the side areas to be reduced in prominence and better integrated into the central domed space.[113] The Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque in Kadırga is one of Sinan's most accomplished designs of his late career and with this type of configuration.[112] In this mosque Sinan completely integrated the supporting columns of the hexagonal baldaquin into the outer walls for the first time, thus creating a unified interior space.[114] He also accomplished a better transition between the domed portico around the courtyard and the higher portico of the mosque façade by adding corner rooms of intermediate height between them.[115] The mosque's interior is notable for the revetment of Iznik tiles on the wall around the mihrab and on the pendentives of the main dome, creating one of the best compositions of tilework decoration in this period.[114]

The Selimiye MosqueSinan's crowning masterpiece is the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne, which was begun in 1568 and completed in 1574 (or possibly 1575).[116][117] It forms the major element of another imperial complex of buildings. The mosque building consists of two equal parts: a rectangular courtyard and a rectangular prayer hall. The prayer hall's interior is notable for being completely dominated by a single massive dome, whose view is unimpeded by the structural elements seen in other large domed mosques before this.[118] This design is the culmination of Sinan's spatial experiments, making use of the octagonal baldaquin as the most effective method of integrating the round dome with the rectangular hall below by minimizing the space occupied by the supporting elements of the dome.[119][120] The dome is supported on eight massive pillars which are partly freestanding but closely integrated with the outer walls. Additional outer buttresses are concealed in the walls of the mosque, allowing the walls in between to be pierced with a large number of windows.[121] Four semi-dome squinches occupy the corners but they are much smaller in proportion to the main dome. Sinan also made good use of the spaces between the pillars and buttresses by filling them with an elevated gallery on the inside and arched porticos on the outside.[122] The elevated galleries inside helped to eliminate what little ground-level space existed beyond the central domed baldaquin structure, ensuring that the dome therefore dominated the view from anywhere a visitor could stand.[122] Sinan's biographies praise the dome for its size and height, which is approximately the same diameter as the Hagia Sophia's main dome and slightly taller;[b] the first time that this had been achieved in Ottoman architecture.[121] It also became the largest dome in the Islamic world at the time.[124] The mihrab, carved in marble, is set within a recessed and slightly elevated apse projecting outward from the rest of the mosque, allowing it to be illuminated by windows on three sides.[122] The walls on either side of the mihrab are decorated with excellent Iznik tiles,[125] as is the sultan's private balcony for prayers in the mosque's eastern corner.[126] The minbar of the mosque is among the finest examples of the stone minbars which by then had become common in Ottoman architecture.[127] The stone surfaces are decorated with arches, pierced geometric motifs, and carved arabesques. The exterior of the mosque is marked by four minarets that are some of the tallest Ottoman minarets ever built, standing at 70.89 meters tall.[121]

Sinan's later works after the Selimiye In 1573 Sinan built the Piyale Pasha Mosque, which is unusual as the only time he built a multi-dome mosque resembling the multi-dome congregational mosques of early Ottoman architecture.[128][129] Another unusual building attributed to Sinan is the Zal Mahmud Pasha Mosque complex near Eyüp. It has an unknown construction date; it could have been built in the 1560s[130] or 1570s,[131] but was definitely completed by 1584.[132] Further afield, he designed the Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Complex in Payas, which was begun years earlier but completed in 1574.[133][134] The complex is a carefully-planned group of buildings centered around an arasta or covered market street. On one side of the street is a small mosque, a tekke (Sufi lodge), a mektep, and a hammam, while on the other side of the street is an imaret, several tabhanes, and a large caravanserai.[133][134] Like the Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Complex in Lüleburgaz, the complex here acted as a kind of staging post for travelers and traders in the region.[108] In 1577 Sinan completed yet another mosque for Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, the Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque in the Azapkapı neighbourhood, for which he employed the octagonal baldaquin design one last time.[135][136] In the precincts of Hagia Sophia he built the Tomb of Selim II, one of the largest Ottoman domed mausoleums, in 1576–1577.[137] In Topkapı Palace one of his most notable works, the Chamber or Pavilion of Murad III, was built in 1578.[138] In 1580 he built the Şemsi Pasha Complex, a small mosque, tomb, and medrese complex on the waterside of Üsküdar which is considered one of the best small mosques he designed.[139][140][141] In 1580–1581 he built the Kılıç Ali Pasha Complex in the Tophane neighbourhood. Notably, this mosque is a miniature version of the Hagia Sophia. It is once again possible that this unusual copying of an earlier monument was a request by the patron, Kılıç Ali Pasha.[142][143]

Sinan's last large-scale commission was the Atik Valide Mosque, founded by Nurbanu Sultan on the southern edge of Üsküdar.[144] It was the largest külliye and mosque complex Sinan built in Istanbul after the Süleymaniye.[139][145] Construction on the complex may have started as early as 1570,[146] with the mosque probably completed by 1579 and work on auxiliary structures continuing after this. Nurbanu died in 1583 but some modifications and additions to her mosque were made between 1584 and 1586.[147] The complex consists of numerous structure across a sprawling site. Unlike the earlier Fatih and Süleymaniye complexes, and despite the large available space, there was no attempt at creating a unified or symmetrical design across the entire complex.[148] This may suggest that Sinan did not regard this characteristic as necessary to the design of an ideal mosque complex,[148] but it has also led to scholarly arguments about whether Sinan was the only one responsible for the design.[149][150] It is likely that the posthumous expansion of the mosque (of 1584–1586) was carried out by Davud Agha, Sinan's later successor.[151][150] The Çemberlitaş Hamam, located across the channel on Divanyolu street, was also built by Sinan to contribute to the revenues of this complex.[152] The plan of the Atik Valide Mosque, as mentioned earlier, is centered on a hexagonal baldaquin again. It partly reverts to the design of the earlier Sinan Pasha Mosque, while combining it with the design of the Kara Ahmed Pasha Mosque and the Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque in Kadırga. Some scholars, such as Doğan Kuban, argue on the basis of this unusual decision that the final design must have been altered by someone other than Sinan, but Godfrey Goodwin argues that there is no clear reason to suppose this.[153][154] The mosque is fronted by a double portico and the whole building is surrounded on three sides by a single large courtyard, which in turn is connected to another courtyard situated on a lower level which served as the madrasa of the complex. Both courtyards are planted with trees which give them the appearance of a garden.[155] Across the street from the mosque and madrasa is a structure composed of many courtyards and domed chambers across a large area, which include the tabhane, the imaret, the darüşşifa, and the caravanserai. The imaret and the tabhane have T-shaped courtyards and are symmetrically positioned on either side of a large central courtyard that divides them. This configuration is unique among Sinan's works.[155]

Among Sinan's last works before his death are the Murad III Mosque in Manisa, built between 1583 and 1586 under the supervision of his assistants Mahmud and Mehmed Agha,[156][157] as well as the modest Ramazan Efendi Mosque in Istanbul, built in 1586.[158][29] The Murad III Mosque (or Muradiye Mosque) has undergone later restorations but the plan of the building is unusual for a Sinan design because the central dome is flanked by semi-vaults instead of semi-domes.[157] The mihrab is set within a shallow vaulted recess projecting from the back of the building, which gives it an almost T-like plan.[157][156] Upon his death in 1588, Sinan was buried in a tomb he designed for himself at a street corner next to the Süleymaniye complex in Istanbul.[156]

Classical architecture after SinanLate 16th centuryDavud Agha succeeded Sinan as chief architect. Among his most notable works, all in Istanbul, are the Cerrahpaşa Mosque (1593), the Koca Sinan Pasha Complex on Divanyolu (1593), the Gazanfer Ağa Medrese complex (1596), and the Tomb of Murad III (completed in 1599).[14][159] Some scholars argue that the Nışançı Mehmed Pasha Mosque (1584–1589), whose architect is unknown, should be attributed to him based on its date and style.[160][161] Scholar Gülrü Necipoğlu suggests that Sinan may have had a role in its design.[162] Its design is considered highly accomplished[161][163] and it may be one of the first mosques to be fronted by a garden courtyard.[161]

Some scholars view Davud Agha's style as essentially conservative and derivative of Sinan's work.[164] Doğan Kuban, who attributes the Nışançı Mehmed Pasha Mosque to him, argues that he was one of the few architects of this period to display great potential and to create designs that went beyond Sinan's designs.[165] He died right before the end of the 16th century.[165] After this, the two largest mosques built in the 17th century were both modelled on the form of the older Şehzade Mosque: the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque and the Yeni Valide Mosque in Eminönü.[166] Early 17th century The Sultan Ahmed I Mosque, also known as the Blue Mosque, was begun in 1609 and completed in 1617.[167] It was designed by Sinan's apprentice, Mehmed Agha.[168] The mosque's size, location, and decoration suggest it was intended to be a rival to the nearby Hagia Sophia.[169] The larger complex includes a market, madrasa, and the Tomb of Ahmed I, while other structures have not survived.[170] In the mosque's prayer hall the central dome is flanked by four semi-domes just like the Şehzade Mosque, with additional smaller semi-domes opening from each larger semi-dome.[171] The four pillars supporting the central dome are massive and more imposing than in Sinan's mosques.[172][173] The lower walls are lavishly decorated with Iznik tiles: historical archives record that over 20,000 tiles were purchased for the purpose.[174] On the outside, Mehmed Agha opted to achieve a "softer" profile with the cascade of domes and the various curving elements, differing from the more dramatic juxtaposition of domes and vertical elements seen in earlier classical mosques by Sinan.[175][176] It is also the only Ottoman mosque to have as many as six minarets.[8] After the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque, no further great imperial mosques dedicated to a sultan were built in Istanbul until the mid-18th century. Mosques continued to be built and dedicated to other dynastic family members, but the tradition of sultans building their own monumental mosques lapsed.[177] Some of the best examples of early 17th-century Ottoman architecture are the Revan Kiosk (1635) and Baghdad Kiosk (1639) in Topkapı Palace, built by Murad IV to commemorate his victories against the Safavids.[178] Both are small pavilions raised on platforms overlooking the palace gardens. Both are harmoniously decorated on the inside and outside with predominantly blue and white tiles and richly-inlaid window shutters.[178]

Later 17th centuryIn the Grand Bazaar of Istanbul, fires and other damages triggered some changes. The bazaar structures were until then entirely built in wood, but some of the street roofing began to be rebuilt with masonry vaulting in the 17th century – closer to its present-day appearance – though the change to masonry was not widespread until after 1750.[179] The commercial district also grew beyond the covered bazaar. The largest caravanserai in Istanbul, the Büyük Valide Han, was built nearby circa 1651 by Kösem Mahpeyker Valide Sultan.[180][181] The Yeni Valide ('New Queen Mother's') Mosque at Eminönü was initially begun by architect Davud Agha in 1597, sponsored by Safiye Sultan. However, Davud Agha's death a year or two after, followed by the death of Safiye Sultan in 1603, caused construction to be abandoned.[182][183] It was only resumed on the initiative of Hatice Turhan Sultan in 1661 and finished in 1663. The complex includes the mosque, a mausoleum for Hatice Turhan, a private pavilion for the sultan and the royal family (Hünkâr Kasrı), and a covered market known as the Egyptian Market (Mısır Çarşısı; known today as the Spice Bazaar). Its courtyard and interior are richly decorated with Iznik or Kütahya tiles, as well as with stone-carved muqarnas and vegetal rumi motifs.[182][183] The similarly named Yeni Valide Mosque complex, built in 1708–1711 in Üsküdar, was one of the last major monuments built in the classical style in Istanbul before the rise of the Tulip Period style.[184][185]

Architecture in the provincesAnatoliaNorthern and central AnatoliaOttoman monuments continued to be constructed across Anatolia in the classical period. In Tokat, the Ali Pasha Mosque (circa 1573) is an important example of the period, though the architect is unknown.[186][187] In Kayseri, the Kurşunlu Mosque (1585), is similar to the Ali Pasha Mosque and was possibly designed by Sinan (whose hometown was Kayseri), although it may have been executed by a local architect.[188][187] The Lala Mustafa Pasha Mosque in Erzurum, completed in 1562–1563 is an interesting example of the classical period. Its plan resembles that of the Şehzade Mosque except that the semi-domes are replaced by cross-ribbed vaults.[189] In Konya, the major work of the classical period is the Selimiye Mosque, dedicated to Selim II. Although it was built during the time of Sinan, its architect and date of construction are not well-documented. It was probably finished before 1574 by an architect sent from Istanbul. Its design is modelled on the form of the original Fatih Mosque in Istanbul, with a central dome, semi-dome at the back, and side aisles covered by smaller domes.[157] The most important classical Ottoman monument in western Anatolia is the Muradiye Mosque in Manisa (mentioned above), designed by Sinan but executed by his assistants.[157]

Southeastern AnatoliaSome regions on the borders of Syria and Mesopotamia resisted assimilation to the culture and architectural styles of the Ottoman capital and continued to be strongly influenced by local styles. Diyarbakir, Van, and Adana were important regional centers in the empire which retained or developed their own local styles.[190] The Great Mosque of Adana, for example, was built under Ottoman rule between 1507 and 1541 but its features are all derived from Syrian and Mamluk traditions.[191] In Bitlis, the Şerefiye Mosque (1528) is the most notable monument from the 16th century, but it is a continuation of older Anatolian Seljuk architecture rather than of contemporary Ottoman mosques.[192] Diyarbakir, a regional capital, includes many Ottoman-style monuments, but the regional style is distinguished by the use of black basalt stone alternating with white stone.[193] The most important monuments are the Fatih Pasha Mosque (mentioned above), the Hadim Ali Pasha Mosque (1534–1537), the Iskender Pasha Mosque (1551), and the Behram Pasha Mosque (1572).[193] The Behram Pasha Mosque, likely designed by an architect sent from Istanbul, is notable as the only building in the region to be decorated with Iznik tiles imported from Istanbul. The mosque is fronted by a double portico of columns and its prayer hall is covered by a large single dome with four small corner semi-domes.[194] Diyarbakir is also home to the Hasan Pasha Han (1573–1575), a finely-built caravanserai with regional decorative details such as muqarnas carvings above the windows.[195] In Van, a few mosques were built in Ottoman style but exemplify the limits of the classical Istanbul style.[191] The Hüsrev Pasha Mosque (1567) and the Kaya Çelebi Mosque (uncertain date but probably slightly before) are the most important examples of the period, although both have been damaged over time.[196][197] Both mosques have a "minimalist" style, consisting simply of a square prayer hall covered by a large dome. The construction of the domes shows signs of Persian influence. The dome of the Kaya Çelebi Mosque has no drum. Both are constructed with alternating layers of black and white stone, similar to Diyarbakir buildings, and both have simple round minarets.[196]

European provincesNearly all the important Ottoman monuments in the Balkan provinces (known as Rumelia to the Ottomans) date from the 16th and 17th century. Building activity was particularly intense in the 16th century and during the reign of Suleiman, even surpassing that of Anatolia, but it declined over the course of the 17th century.[198] Sarajevo, Mostar, Skopje, Plovdiv and Thessaloniki, were among the most important Ottoman cities in the region and many of them contain monuments from the classical period, although some cities, like Skopje, were severely damaged in the wars of the late 17th century.[199] As in other provincial areas of the empire, mosques in the Balkans generally consisted of the single-dome type with one minaret, though mosques with sloped wooden roofs were also built.[200] Western Balkans One of the most beautiful and famous Ottoman monuments in the Balkans is the single-span bridge known as Stari Most in Mostar (present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina), which was designed or completed by Hayreddin, one of Sinan's assistants.[201] It was originally built between 1557 and 1566 by order of sultan Suleiman.[202][203] Other notable bridges from the same period and region include the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad (1577) and the Arslanağa Bridge in Trebinje (1573 or 1574).[204] The most important examples of mosques in present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina are nearly all from the 16th century, including: the Sinan Mosque (1570) in Cajnice, the Kethüda Mosque (1564) and Karagöz Mehmed Bey Mosque (1569) in Mostar, the Lala Pasha Mosque (1577) in Livno, the Ferhad Pasha Mosque (1579) in Banja Luka, and the Gazi Hüsrev Pasha Mosque (1530), Ferhad Pasha Mosque (1561), and Ali Pasha Mosque (1561) in Sarajevo.[205] Gazi Hüsrev Bey, the Ottoman governor of the Bosnian province, was also instrumental in establishing Sarajevo as a model Ottoman town.[206] He founded the Gazi Hüsrev Pasha (or Gazi Hüsrev Bey) Mosque as part of an extensive külliye complex similar to those built in the Ottoman capitals. In addition to the mosque, the complex includes a tabhane, an imaret, a madrasa, a zaviye or khanqah (Sufi lodge), a library, an arasta (market), a caravanserai, and a hammam.[206] The mosque's configuration is similar to the late-15th-century Atik Ali Pasha Mosque in Istanbul, consisting of a large central dome, a semi-dome behind it, and a two smaller domed chambers to either side. As a result, its design is closer to 15th-century Ottoman architecture than to the 16th-century classical style.[207] Among the other Sarajevo mosques, the Ali Pasha Mosque, built three decades later, is a simple but distinctly classical-style mosque.[208] In Serbia, the city of Belgrade was once an important Ottoman city with hundreds of mosques, but almost no Ottoman monuments have survived to the present day. The only preserved mosque in the city is the Bayraklı Mosque from 1660 to 1668.[209][210] In Prizren, present-day Kosovo, the largest mosque is the Sofu Sinan Pasha Mosque, built by a vizier in 1613 or 1615. It is a single-domed mosque and one of the most monumental Ottoman mosques in the Balkans.[211][212] In Gjakovica, the small Hadum Mosque is another notable example that dates from the 1590s.[213][214][215] In Albania, where much of the population converted to Islam under Ottoman rule, many mosques were constructed but very few old mosques have retained their original appearance due to later repairs and reconstructions. The most important examples were built in the major cities of Berat, Elbasan, and Shkodër.[216]

GreeceIn Greece, few major Ottoman monuments have survived, although various small mosques, military and commercial structures, and examples of domestic architecture have been preserved.[218] In the city of Trikala, the Osman Shah Mosque was commissioned by the governor of the same name, a nephew of Sultan Suleiman. It was built in the 1560s from a design by Sinan. The mosque is a square chamber covered by a single dome and preceded by a domed portico. Osman Shah was buried in an adjacent mausoleum in 1570.[219] Notable examples have also been preserved in the Greek islands such as at Rhodes, where the Yeni Hammam, a large baths complex, and the Suleiman Mosque, a religious complex built in the sultan's name, are still preserved from the 16th century.[218][220] Crete was only conquered by the Ottomans in 1645, long after mainland Greece. The Mosque of the Janissaries in Chania, which dates from that same year, is the oldest mosque on the island.[221] The Ibrahim Han Mosque in Rethymno, a simple square domed building, was built in 1646.[222] In Athens, the only preserved major mosque, the Fethiye Mosque, dates from 1670 to 1671. It replicates the design of the Yeni Valide Mosque completed in Istanbul in 1663, but on a smaller scale.[223][c]

BulgariaIn Sofia, present-day Bulgaria, the Banya Bashi (Banyabaşı) Mosque has been dated to 1566 and its design attributed to Sinan by Turkish historian Ekrem Hakkı Ayverdi, though the evidence for Sinan's involvement is uncertain.[224] It was partially reconstructed in modern times[224] and is the only mosque in Sofia still operating today.[225] The Ferid Ahmed Bey Mosque in Kyustendil, built by a local governor in 1575–1577,[226] is an unusual example because it has one main dome preceded by a single half-dome near the entrance, an anomaly perhaps explained by the employ of a local architect.[227] In 1584–1585 the Harmanli Menzil Complex was founded by Siyavuş Pasha in Harmanli, on the road between Istanbul and Belgrade. It was one of the most extensive complexes of its kind in Bulgaria and consisted of a caravanserai, a mosque, a madrasa, an imaret, and a bridge over the river.[228] In Razgrad, the Ibrahim Pasha Mosque, constructed in 1616, is interesting for the presence of pointed turrets at the corners of the dome which serve no structural purpose.[227] In Plovdiv, the most important Ottoman town of the area, a large caravanserai, the Kurşunlu Han, was built in the 17th century near the main bazaar,[227] but both the bazaar and the caravanserai were demolished around 1970.[229]

RomaniaIn Wallachia (present-day Romania) and Moldova, relatively few monuments from the Ottoman period have survived. The few surviving mosques are often wooden structures with a flat or sloped roof, a single minaret, and sometimes a portico with pointed arches, which seem to mark a local style. Examples of these include the Ismihan Sultan Mosque in Mangalia, sponsored by Ismihan Sultan (d. 1585) in the 16th century, and the Gazi Ali Pasha Mosque in Babadag, founded in the early 17th century, although both mosques were subsequently rebuilt in later periods.[230]

HungaryIn Hungary, many small single-domed mosques were built along the same lines as those elsewhere in the Balkans. Some examples are the Gazi Kasım Pasha Mosque (later converted to a church) and the Yakovalı Hasan Pasha Mosque, both built in Pécs during the second half of the 16th century.[230][231][232] The relatively small proportion of Muslim inhabitants in Hungary made the commission of extensive religious complexes less necessary, but some madrasas, Sufi tekkes, and hammams are known to have been built.[230] Four hammams, built around thermal springs, have been preserved in Budapest today, mostly built between 1560 and 1590, with later additions and expansions after the end of Ottoman rule. The four are known today as the Király Baths, Rudas Baths, Rác Baths, and the Csâszâr Baths.[233][234][235][236]

Crimea The Crimean Khans were vassals of the Ottomans since 1475.[237] Khan Devlet I Giray (r. 1551–1577) sponsored the construction of an Ottoman-style mosque, the Khan Mosque,[238] in the port city of Gözleve (now Yevpatoria). It was likely designed by Sinan and approved by Sultan Süleyman when Devlet left Istanbul in 1551.[237] As with many other provincial works, Sinan himself would not have supervised the construction and a royal architect from Istanbul was likely sent in his place. An inscription on the mosque entrance dates its construction to 1552. The mosque's design is a miniature reproduction of the original 15th-century Fatih Mosque in Istanbul, but without the courtyard. The building's present decoration dates from later renovations.[237] Levant, Mesopotamia, and Egypt In the Levant and Egypt, the local Mamluk-era style was largely continued and blended with Ottoman architecture to varying degrees.[239][240] In some cases, such as at the Çoban Mustafa Pasha Mosque in Gebze, governors who had served in these regions later enlisted craftsmen from those regions to work on their own mosques in the heartlands of the empire.[241] In Syria, the Sinan-designed Sulaymaniyya Takiyya in Damascus (mentioned above) is one of the major classical Ottoman works in the city. In Aleppo, the Hüsrev Pasha Mosque (also mentioned above) was one of Sinan's earliest works, though it may have been finished by others after he left for Istanbul.[43] Other examples designed by local architects in Damascus include the Dervish Pasha Mosque (1571) and the Sinan Pasha Mosque (1585).[201] Sultan Suleiman also devoted considerable patronage in Jerusalem, where he rebuilt the city walls in their current form between 1537 and 1541, renovated the Dome of the Rock (decorating it with Ottoman tiles), and endowed the city with new charitable foundations such as public fountains and a soup kitchen.[242]  In Cairo, Egypt, the Mosque of Suleyman Pasha inside the Cairo Citadel is the closest representative of classical 16th-century Ottoman mosques in the city, although a few of its features draw on the local Mamluk-Cairene style.[243][244][245] It has a central dome and three semi-domes.[246] The Sinan Pasha Mosque (1571) in the Bulaq neighbourhood of Cairo is somewhat less Ottoman in character and more heavily influenced by local traditions, but it is also one of the most successful mosques of this period blending these two traditions.[243][247][248][249] It consists of a large single-domed prayer hall surrounded by a domed portico on three sides, both typical Ottoman features. The multi-lobed pendentives of the dome, the decoration of the mihrab, and the shape of the windows are all in local styles.[239][250] The Mosque of Malika Safiyya (1610) was probably built by local architects commissioned to design an Istanbul-style mosque. The feature most reminiscent of Istanbul is the square courtyard that precedes the prayer hall, while the prayer hall has a central dome surrounded by smaller domes.[241] Despite local influences, however, most Egyptian mosques of the period consistently adopt the pointed Ottoman style of minaret rather than the more ornate traditional Mamluk-style minaret, which is one of the features clearly denoting Ottoman hegemony in the urban landscape.[241][240] In Baghdad, Iraq, Ottoman mosques were built more or less entirely according to local traditions. One of the earliest mosques was the "Palace Mosque" built in 1534 under Sultan Suleiman. The Muradiye (or al-Muradiyya) Mosque (1567–1570) is a later example with a central dome chamber and smaller domed aisles on either side.[200] Maghreb (Algeria and Tunisia) Like Egypt and Syria, the Maghreb region of North Africa had its own distinctive styles of architecture during the Islamic period, commonly referred to as "Moorish" architecture. After Ottoman domination was established over present-day Tunisia and Algeria in the 16th century, this local architecture was blended with contemporary Ottoman architecture.[251] Tunisia and Algeria, as separate provinces that eventually became semi-autonomous in the later 17th century, each developed local flavours of this mix. In Tunisia, the traditional square-shaft minarets of western mosques were replaced with the Ottoman "pencil"-shaped minarets but the traditional sloped wooden roofs of buildings continued to be standard, with the exception of the Sidi Mahrez Mosque at the end of the 17th century.[251] In Algeria, by contrast, the traditional square minarets continued to be built instead of the Ottoman-style minaret, but mosques in Algiers began to be built with their own local interpretations of the Ottoman central-domed mosque model, with the most notable example being the New Mosque commissioned by local Janissaries in 1660.[251] End of the classical style From the 18th century onward European influences were introduced into Ottoman architecture as the Ottoman Empire itself became more open to outside influences. The term “Baroque” is sometimes applied more widely to Ottoman art and architecture across the 18th century including the Tulip Period.[252][253] In more specific terms, however, the period after the 17th century is marked by several different styles.[254] After the Tulip Period, Ottoman architecture openly imitated European architecture, so that architectural and decorative trends in Europe were mirrored in the Ottoman Empire at the same time or after a short delay.[255] During the 1740s a new Ottoman or Turkish "Baroque" style emerged in its full expression and rapidly replaced the style of the Tulip Period.[256][254] This shift signaled the final end to the Classical style.[257] Changes were especially evident in the ornamentation and details of new buildings rather than in their overall forms, though new building types were eventually introduced from European influences as well.[253] The most important monument heralding the new Ottoman Baroque style is the Nuruosmaniye Mosque complex, begun by Mahmud I in October 1748 and completed by his successor, Osman III (to whom it is dedicated), in December 1755.[258] Kuban describes it as the "most important monumental construction after the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne", marking the integration of European culture into Ottoman architecture and the rejection of the classical Ottoman style.[259]  Nonetheless, the classical style was still employed or imitated on some later occasions where other contemporary styles were deemed less suitable for particular monuments. For example, a sense of historicism in Ottoman architecture of the 18th century is evident in Mustafa III's reconstruction of the Fatih Mosque after the 1766 earthquake that partially destroyed it. The new Fatih Mosque was completed in 1771 and it neither reproduced the appearance of the original 15th-century building nor followed the contemporary Baroque style. It was instead modelled on the 16th-century Şehzade Mosque built by Sinan – whose design had in turn been repeated in major 17th-century mosques like the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque and the New Mosque. This probably indicates that contemporary builders saw the new Baroque style as inappropriate for the appearance of an ancient mosque embedded in the mythology of the city's 1453 conquest. At the same time, it showed that Sinan's architecture was associated with the Ottoman golden age and thus appeared as an appropriate model to imitate, despite the anachronism.[260] By contrast, however, the nearby tomb of Mehmed II, which was rebuilt at the same time, is in a fully Baroque style.[261] Selim III (r. 1789–1807) was responsible for rebuilding the Eyüp Sultan Mosque between 1798 and 1800.[262][263] This mosque is located next to the tomb of Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, an important Islamic religious site in the area of Istanbul originally built by Mehmed II. The new mosque made use of the classical Ottoman tradition by following the octagonal baldaquin design, similar to the Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque in the Azapkapı neighbourhood, but much of its decoration is in the contemporary Baroque style.[262][264][265] See alsoNotes

References

Bibliography

|

||||

![Tombs of Gazi Hüsrev Pasha and Murad Bey in the Gazi Hüsrev Pasha Complex[217]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ae/Gazi_Husrev-begovo_turbe.jpg/120px-Gazi_Husrev-begovo_turbe.jpg)