|

Coronation of the Hungarian monarch The coronation of the Hungarian monarch was a ceremony in which the king or queen of the Kingdom of Hungary was formally crowned and invested with regalia. It corresponded to the coronation ceremonies in other European monarchies. While in countries like France and England the king's reign began immediately upon the death of his predecessor, in Hungary the coronation was absolutely indispensable: if it were not properly executed, the Kingdom stayed "orphaned". All monarchs had to be crowned as King of Hungary in order to promulgate laws and exercise his royal prerogatives in the Kingdom of Hungary.[1][2][3] Starting from the Golden Bull of 1222, all new Hungarian monarchs had to take a coronation oath, by which they had to agree to uphold the constitutional arrangements of the country, and to preserve the liberties of their subjects and the territorial integrity of the realm.[4] History

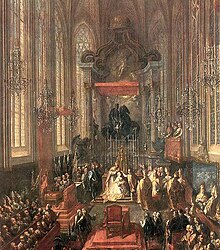

In the Middle Ages, all Hungarian coronations took place in Székesfehérvár Basilica, the burial place of the first crowned ruler of Hungary, Saint Stephen I. The Archbishop of Esztergom anointed the king or queen (however the Bishop of Veszprém claimed many times his right of crowning the queen consort, as an established tradition). The Archbishop then placed the Holy Crown of Hungary and the mantle of Saint Stephen on the head of the anointed person. The king was given a sceptre and a sword which denoted military power. Upon enthronement, the newly crowned king took the traditional coronation oath and promised to respect the people's rights. The Archbishop of Esztergom refused to preside over the coronation ceremony on three occasions; in such cases, the Archbishop of Kalocsa, the second-ranking prelate, performed the coronation.[5] Other clergy and members of the nobility also had roles; most participants in the ceremony were required to wear ceremonial uniforms or robes. Many other government officials and guests attended, including representatives of foreign countries. According to legend, the first Hungarian monarch, Saint Stephen I, was crowned in the St Adalbert Cathedral in Esztergom on 25 December 1000 or 1 January 1001. After his death he was buried in the Cathedral of Székesfehérvár which he started to build and where he had buried his son Saint Emeric. This cathedral became the traditional coronation church for the subsequent Hungarian monarchs starting with Peter Orseolo, Saint Stephen's nephew in 1038 up to John Zápolya coronation, before the Battle of Mohács in 1526. The huge Romanesque cathedral was one of the biggest of its kind in Europe, and later became the burying place of the medieval Hungarian monarchs. After the death of King Andrew III, the last male member of the House of Árpád, in 1301, the successful claimant to the throne was a descendant of King Stephen V, and from the Capetian House of Anjou: King Charles I. However he had to be crowned three times, because of internal conflicts with the aristocrats, who were unwilling to accept his rule. He was crowned for the first time in May 1301 by the archbishop of Esztergom in the city of Esztergom, but with a simple crown. This meant that two of the conditions for his legitimacy were not fulfilled. After this, he was crowned for the second time in June 1309 by the archbishop of Esztergom, but in the city of Buda, and with a provisional crown, because the Crown of Saint Stephen was not yet in his possession. Finally, after obtaining the Holy Crown, Charles was crowned for his third time, but now in the Cathedral of Székesfehérvár, by the archbishop of Esztergom and with the Holy Crown. After the death of King Albert in 1439, his widow, Elizabeth of Luxembourg, ordered one of her handmaidens to steal the Holy Crown that was kept in the castle of Visegrád, and with it she could crown her newborn son as King Ladislaus V. The relevance of the strict conditions from the coronation were fulfilled without questioning[clarification needed], and for example King Matthias Corvinus ascended to the throne in 1458, but he could be crowned with the Holy Crown only in 1464 after he recovered it from the hands of Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor. Only after this did Matthias start his internal and institutional reforms in the Kingdom, having been considered as the legitimate ruler of Hungary. When the Kingdom of Hungary was occupied by the Ottoman armies in the decades after the Battle of Mohács in 1526, the following Habsburg monarchs could not reach the city of Székesfehérvár (it lost in 1543) to be crowned. So in 1563 St. Martin's Cathedral in Pressburg (today Bratislava) became the cathedral of coronation and remained so until the coronation of 1830, after which coronations returned to Székesfehérvár, but not to the massive cathedral built by Saint Stephen, because that had been destroyed in 1601 when the Christian armies besieged the city. The Ottomans used the cathedral for gunpowder storage, and during the attack the building was destroyed. Legal requirements for coronationRulers of Hungary were not considered legitimate monarchs until they were crowned King of Hungary with the Holy Crown of Hungary. As women were not considered fit to rule Hungary, the two queens regnant, Mary and Maria Theresa, were crowned kings (Rex Hungariae[6]) of Hungary.[7] Even during the long personal union of Austria and the Kingdom of Hungary, the Habsburg Emperor had to be crowned King of Hungary in order to promulgate laws there or exercise his royal prerogatives. The only Habsburg who reigned without being crowned in Hungary was Joseph II, who was called kalapos király in Hungarian ("the hatted king"). Before him, John Sigismund Zápolya and Gabriel Bethlen were elected kings, but they were never crowned nor generally accepted, and Imre Thököly was only declared King of Upper Hungary by Sultan Mehmed IV without being elected and crowned. The final such rite was held in Budapest on 30 December 1916, when Emperor Charles I of Austria and Empress Zita were crowned as King Charles IV and Queen Zita of Hungary. The ceremony was rushed, due both to the war and the constitutional requirement for the Hungarian monarch to approve the state budget prior to the end of the calendar year. Charles IV's coronation was filmed however, and thus remains the only coronation of a Hungarian monarch ever documented in this way. The Austro-Hungarian Empire dissolved with the end of World War I, although Hungary would later restore a titular monarchy from 1920-46—while forbidding Charles to resume the throne. A communist takeover in 1945 spelled the final end of this "kingdom without a king". Legal requirements in the Middle AgesBy the end of the 13th century, the customs of the Kingdom of Hungary prescribed that all the following (three requirements) shall be fulfilled when a new king ascended the throne:

Afterwards, from 1387, the customs also required the election of the new king. Although, this requirement disappeared when the principle of the hereditary monarchy came in 1688. Afterwards, kings were required to issue a formal declaration (credentionales litterae) in which they swore to respecting the constitution of the kingdom. The first requirement (coronation by the Archbishop of Esztergom) was confirmed by Béla III of Hungary, who had been crowned by the Archbishop of Kalocsa, based on the special authorisation of Pope Alexander III. However, after his coronation, he declared that his coronation would not harm the customary claim of the Archbishops of Esztergom to crown the kings. In 1211, Pope Innocent III refused to confirm the agreement of Archbishop John of Esztergom and Archbishop Berthold of Kalocsa, on the transfer of the claim. The Pope declared that the Archbishop of Esztergom alone, and no other prelate, was entitled to crown the King of Hungary. CeremonyThe Hungarian coronation ritual closely follows the Roman ritual for the consecration and coronation of kings (De Benedictione et Coronatione Regis) found in the Roman Pontifical (Pontificale Romanum). In fact, for the coronation of King Franz Joseph I and Queen Elisabeth, the Roman Pontifical of Clement VII, revised by Benedict XIV, was used rather than the traditional Hungarian ritual. According to ancient custom just before the coronation proper, the Archbishop of Esztergom handed the Holy Crown to the Count Palatine (Nádor) who lifted it up and showed it to the people and asked if they accept the elect as their king (this is part of the Coronational Ordo of Mainz, which historians like György Györffy theorized that could be the one used). The people responded, "Agreed, so be it, long live the king!" A bishop then presented the king to the Archbishop requesting him in the name of the Church to proceed with his coronation. The Archbishop asked the king three questions—if the king agreed to protect the holy faith, if he agreed to protect the holy Church and if he agreed to protect the kingdom—to each of which the king responded, "I will." The king then took the oath, "I, nodding to God, confess myself to be King (N) and I promise before God and his Angels henceforth the law, justice, and peace of the Church of God, and the people subject to me to be able and to know, to do and to keep, safe and worthy of the mercy of God, as in the counsel of the faithful I will be able to find better ones. To the pontiffs of the Churches of God, to present a congenial and canonical honor; and to observe inviolably those which have been conferred and returned to the Churches by Emperors and Kings. To render due honor to my abbots, counts, and vassals, according to the counsel of my faithful."[8] Then he touches with both hands the book of the Gospels, which the Metropolitan holds open before him, saying: So God help me, and these holy Gospels of God. Afterwards the King-elect reverently kisses the hand of the Metropolitan. The Archbishop then said the prayer:

The king then prostrated himself before the altar as the Litany of the Saints was sung. After this the Archbishop anointed the king on his right forearm and between his shoulders as he said the prayer:

Then the Mass for the day was begun with the Archbishop saying after the Collect for the day, the additional prayer, "God who reigns over all," etc. After the Gradual and Alleluia, the king was invested with the Hungarian regalia. The king was first invested and girded with the Sword of St. Stephen with the formula:

The king then brandished the sword three times. Then the Holy Crown is placed upon him, which all the Prelates who are present, being ready, hold in their hands, taken from the altar by the Metropolitan, the Metropolitan himself directing it, placing it on his head, and saying: “Receive the crown of the kingdom, which, though by the unworthy, is nevertheless placed on your head by the hands of the bishops. In the name of the +Father, and of the +Son, and of the +Holy Spirit, you understand to signify the glory of holiness, and honor, and the work of courage, and through this you are not ignorant of our ministry. So that, just as we inwardly are understood to be shepherds and rulers of souls, so you also outwardly worship God, and actively defend against all adversities the Church of Christ, and the kingdom given to you by God, and through the office of our blessing in the place of the Apostles and of all the Saints, in your government may you always appear as a useful executor of the commission, and a profitable ruler; that among the glorious athletes, adorned with the jewels of virtue, and crowned with the prize of eternal happiness, with our Redeemer and Savior Jesus Christ, whose name and virtue you believe to bear, you may be glorified without end. God lives and rules with the Father and the Holy Spirit forever and ever. R. Amen.” This is the same formula for the Crown as that found in the Roman Pontifical of Clement VII.[9] Next, the king was given the Scepter with the formula:

Then, the Orb was placed into his left hand without any formula, and the king was enthroned with the formula:

According to some accounts[10] the Te Deum was then sung followed by the responsory:

The Archbishop then said either the prayer, "God who made Moses victorious" or the prayer "Inerrant God." The people then greeted the king with the words, "Life, health, happiness, victory!" after which the Mass was resumed to its conclusion.[11] The most impressive part was when the sovereign in full regalia rode on horseback up an artificial hill constructed out of soil from all parts of the kingdom. On top of the hill, the sovereign would point to all four corners with the royal sword and swear to protect the kingdom and all its subjects. After that, the nobles and the subjects would hail their new sovereigns with cries of 'hurray' three times and paying homage. After the ceremony, the royal couple would proceed with great fanfare to the royal castle to receive the homage. Coronation dates 1000–1916  Basilica in Székesfehérvár 1000-1543

In Posonium/Bratislava, Sopron and Buda(pest) 1543-1916

References

External links |