|

Criminal justice

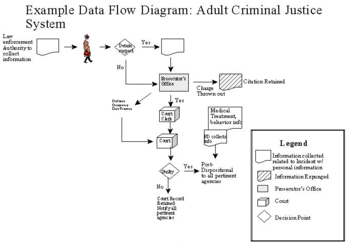

Criminal justice is the delivery of justice to those who have been accused of committing crimes. The criminal justice system is a series of government agencies and institutions. Goals include the rehabilitation of offenders, preventing other crimes, and moral support for victims. The primary institutions of the criminal justice system are the police, prosecution and defense lawyers, the courts and the prisons system. Criminal justice systemDefinitionThe criminal justice system consists of three main parts:

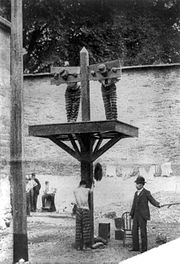

In the criminal justice system, these distinct agencies operate together as the principal means of maintaining the rule of law within society.[1]  Law enforcementThe first contact a defendant has with the criminal justice system is usually with the police (or law enforcement) who investigates the suspected wrongdoing and makes an arrest, but if the suspect is dangerous to the whole nation, a national level law enforcement agency is called in. When warranted, law enforcement agencies or police officers are empowered to use force and other forms of legal coercion and means to effect public and social order. The term is most commonly associated with police departments of a state that are authorized to exercise the police power of that state within a defined legal or territorial area of responsibility. The word comes from the Latin politia ("civil administration"), which itself derives from the Ancient Greek: πόλις for polis ("city").[2] The first police force comparable to the present-day police was established in 1667 under King Louis XIV in France, although modern police usually trace their origins to the 1800 establishment of the Thames River Police in London, the Glasgow Police, and the Napoleonic police of Paris.[3][4][5] Police are primarily concerned with keeping the peace and enforcing criminal law based on their particular mission and jurisdiction. Formed in 1908, the Federal Bureau of Investigation began as an entity which could investigate and enforce specific federal laws as an investigative and "law enforcement agency" in the United States;[6] this, however, has constituted only a small portion of overall policing activity.[7] Policing has included an array of activities in different contexts, but the predominant ones are concerned with order maintenance and the provision of services.[8] During modern times, such endeavors contribute toward fulfilling a shared mission among law enforcement organizations with respect to the traditional policing mission of deterring crime and maintaining societal order.[9] Courts The courts serve as the venue where disputes are settled and justice is then administered. With regard to criminal justice, there are a number of critical people in any court setting. These critical people are referred to as the courtroom work group and include both professional and non professional individuals. These include the judge, prosecutor, and the defense attorney. The judge, or magistrate, is a person, elected or appointed, who is knowledgeable in the law, and whose function is to objectively administer the legal proceedings and offer a final decision to dispose of a case. In the U.S. and in a growing number of nations, guilt or innocence (although in the U.S. a jury can never find a defendant "innocent" but rather "not guilty") is decided through the adversarial system. In this system, two parties will both offer their version of events and argue their case before the court (sometimes before a judge or panel of judges, sometimes before a jury). The case should be decided in favor of the party who offers the most sound and compelling arguments based on the law as applied to the facts of the case. The prosecutor, or district attorney, is a lawyer who brings charges against a person, persons or corporate entity. It is the prosecutor's duty to explain to the court what crime was committed and to detail what evidence has been found which incriminates the accused. The prosecutor should not be confused with a plaintiff or plaintiff's counsel. Although both serve the function of bringing a complaint before the court, the prosecutor is a servant of the state who makes accusations on behalf of the state in criminal proceedings, while the plaintiff is the complaining party in civil proceedings. A defense attorney counsels the accused on the a legal process, likely outcomes for the accused and suggests strategies. The accused, not the lawyer, has the right to make final decisions regarding a number of fundamental points, including whether to testify, and to accept a plea offer or demand a jury trial in appropriate cases. It is the defense attorney's duty to represent the interests of the client, raise procedural and evidentiary issues, and hold the prosecution to its burden of proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Defense counsel may challenge evidence presented by the prosecution or present exculpatory evidence and argue on behalf of their client. At trial, the defense attorney may attempt to offer a rebuttal to the prosecutor's accusations. In the U.S., accused people are entitled to a government-paid defense attorney if the individual is in jeopardy of losing life and/or liberty. Those who cannot afford a private attorney may be provided one by the state. Historically, however, the right to a defense attorney has not always been universal. For example, in Tudor England criminals accused of treason were not permitted to offer arguments in their defense. In many jurisdictions, there is no right to an appointed attorney, if the accused is not in jeopardy of losing his or her liberty. The final determination of guilt or innocence is typically made by a third party, who is supposed to be disinterested. This function may be performed by a judge, a panel of judges, or a jury panel composed of unbiased citizens. This process varies depending on the laws of the specific jurisdiction. In some places the panel (be it judges or a jury) is required to issue a unanimous decision, while in others only a majority vote is required. In America, this process depends on the state, level of court, and even agreements between the prosecuting and defending parties. Some nations do not use juries at all, or rely on theological or military authorities to issue verdicts. Some cases can be disposed of without the need for a trial. In fact, the vast majority are. If the accused confesses his or her guilt, a shorter process may be employed and a judgment may be rendered more quickly. Some nations, such as America, allow plea bargaining in which the accused pleads guilty, nolo contendere or not guilty, and may accept a diversion program or reduced punishment, where the prosecution's case is weak or in exchange for the cooperation of the accused against other people. This reduced sentence is sometimes a reward for sparing the state the expense of a formal trial. Many nations do not permit the use of plea bargaining, believing that it coerces innocent people to plead guilty in an attempt to avoid a harsh punishment. The courts nowadays are seeking alternative measures as opposed to throwing someone into prison right away.[10] The entire trial process, whatever the country, is fraught with problems and subject to criticism. Bias and discrimination form an ever-present threat to an objective decision. Any prejudice on the part of the lawyers, the judge, or jury members threatens to destroy the court's credibility. Some people argue that the often Byzantine rules governing courtroom conduct and processes restrict a layman's ability to participate, essentially reducing the legal process to a battle between the lawyers. In this case, the criticism is that the decision is based less on sound justice and more on the lawyer's eloquence and charisma. This is a particular problem when the lawyer performs in a substandard manner. The jury process is another area of frequent criticism, as there are few mechanisms to guard against poor judgment or incompetence on the part of the layman jurors. Judges themselves are very subject to bias subject to things as ordinary as the length of time since their last break.[11] Manipulations of the court system by defense and prosecution attorneys, law enforcement as well as the defendants have occurred and there have been cases where justice was denied.[12][13] Corrections and rehabilitation Offenders are then turned over to the correctional authorities, from the court system after the accused has been found guilty. Like all other aspects of criminal justice, the administration of punishment has taken many different forms throughout history. Early on, when civilizations lacked the resources necessary to construct and maintain prisons, exile and execution were the primary forms of punishment. Historically shame punishments and exile have also been used as forms of censure. The most publicly visible form of punishment in the modern era is the prison. Prisons may serve as detention centers for prisoners after trial. For containment of the accused, jails are used. Early prisons were used primarily to sequester criminals and little thought was given to living conditions within their walls. In America, the Quaker movement is commonly credited with establishing the idea that prisons should be used to reform criminals. This can be seen as a critical moment in the debate regarding the purpose of punishment.  Punishment (in the form of prison time) may serve a variety of purposes. First, and most obviously, the incarceration of criminals removes them from the general population and inhibits their ability to perpetrate further crimes. A new goal of prison punishments is to offer criminals a chance to be rehabilitated. Many modern prisons offer schooling or job training to prisoners as a chance to learn a vocation and thereby earn a legitimate living when they are returned to society. Religious institutions also have a presence in many prisons, with the goal of teaching ethics and instilling a sense of morality in the prisoners. If a prisoner is released before his time is served, he is released as a parole. This means that they are released, but the restrictions are greater than that of someone on probation. There are numerous other forms of punishment which are commonly used in conjunction with or in place of prison terms. Monetary fines are one of the oldest forms of punishment still used today. These fines may be paid to the state or to the victims as a form of reparation. Probation and house arrest are also sanctions which seek to limit a person's mobility and his or her opportunities to commit crimes without actually placing them in a prison setting. Furthermore, many jurisdictions may require some form of public or community service as a form of reparations for lesser offenses. In Corrections, the department ensures court-ordered, pre-sentence chemical dependency assessments, related Drug Offender Sentencing Alternative specific examinations and treatment will occur for offenders sentenced to Drug Offender Sentencing Alternative in compliance with RCW 9.94A.660. Execution or capital punishment is still used around the world. Its use is one of the most heavily debated aspects of the criminal justice system. Some societies are willing to use executions as a form of political control, or for relatively minor misdeeds. Other societies reserve execution for only the most sinister and brutal offenses. Others still have discontinued the practice entirely, accepting the use of execution to be excessively cruel and/or irreversible in case of an erroneous conviction.[14] Academic disciplineThe functional study of criminal justice is at times distinct from criminology, which involves the study of crime as a social phenomenon, causes of crime, criminal behavior, and other aspects of crime; although in most cases today, criminal justice as a field of study is used as a synonym for criminology and the sociology of law. It emerged as an academic discipline in the 1920s, beginning with Berkeley police chief August Vollmer who established a criminal justice program at the University of California, Berkeley in 1916.[15] Vollmer's work was carried on by his student, O.W. Wilson, who led efforts to professionalize policing and reduce corruption. Other programs were established in the United States at Indiana University, Michigan State University, San Jose State University, and the University of Washington.[16] As of 1950, criminal justice students were estimated to number less than 1,000.[citation needed] Until the 1960s, the primary focus of criminal justice in the United States was on policing and police science. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, crime rates soared and social issues took center stage in the public eye. A number of new laws and studies focused federal resources on researching new approaches to crime control. The Warren Court (the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren), issued a series of rulings which redefined citizen's rights and substantially altered the powers and responsibilities of police and the courts. The Civil Rights Era offered significant legal and ethical challenges to the status quo. In the late 1960s, with the establishment of the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) and associated policy changes that resulted with the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968. The LEAA provided grants for criminology research, focusing on social aspects of crime. By the 1970s, there were 729 academic programs in criminology and criminal justice in the United States.[16] Largely thanks to the Law Enforcement Education Program, criminal justice students numbered over 100,000 by 1975. Over time, scholars of criminal justice began to include criminology, sociology, and psychology, among others, to provide a more comprehensive view of the criminal justice system and the root causes of crime. Criminal justice studies now combine the practical and technical policing skills with a study of social deviance as a whole. Criminal justice degrees are offered at both the two-year community college and four-year university level. Community college criminal justice programs include the Associate of Arts (AA), Associate of Science (AS), and the Associate of Applied Science (AAS) degrees. Criminal justice degree programs at four-year institutions typically include coursework in statistics, methods of research, criminal justice, policing, U.S. court systems, criminal courts, corrections, community corrections, criminal procedure, criminal law, victimology, juvenile justice, and a variety of special topics. A number of universities offer, bachelor's, academic minors, graduate certificates, master's, and doctoral degrees in Criminal Justice; Criminology, Law and Society; Administration of Justice; or a specially designated Bachelor of Criminal Justice degree. Theories of criminal justiceTheories of criminal justice include utilitarian justice,[17] retributive justice,[18] restorative justice.[19] They can work through deterrence,[20] rehabilitation[21] or incapacitation. History The modern criminal justice system has evolved since ancient times, with new forms of punishment, added rights for offenders and victims, and policing reforms. These developments have reflected changing customs, political ideals, and economic conditions. In ancient times through the Middle Ages, exile was a common form of punishment. During the Middle Ages, payment to the victim (or the victim's family), known as wergild, was another common punishment, including for violent crimes. For those who could not afford to buy their way out of punishment, harsh penalties included various forms of corporal punishment. These included mutilation, branding, and flogging, as well as execution.[citation needed] Though a prison, Le Stinche, existed as early as the 14th century in Florence,[22] incarceration was not widely used until the 19th century. Correctional reform in the United States was first initiated by William Penn, towards the end of the 17th century. For a time, Pennsylvania's criminal code was revised to forbid torture and other forms of cruel punishment, with jails and prisons replacing corporal punishment. These reforms were reverted, upon Penn's death in 1718. Under pressure from a group of Quakers, these reforms were revived in Pennsylvania toward the end of the 18th century, and led to a marked drop in Pennsylvania's crime rate. Patrick Colquhoun, Henry Fielding and others led significant reforms during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[23] The development of a modern criminal justice system was contemporary to the formation of the concept of a nation-state, later defined by German sociologist Max Weber as establishing a "monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force", which was exercised in the criminal justice case by the police.[24][25][26][27] Modern policeThe first modern police force is commonly said to be the Metropolitan Police in London, established in 1829 by Sir Robert Peel.[28][29] Based on the Peelian principles, it promoted the preventive role of police as a deterrent to urban crime and disorder.[30][31] In the United States, police departments were first established in Boston in 1838, and New York City in 1844. Early on, police were not respected by the community, as corruption was rampant. In the 1920s, led by Berkeley, California, police chief, August Vollmer and O.W. Wilson, police began to professionalize, adopt new technologies, and place emphasis on training and professional qualifications of new hires. Despite such reforms, police agencies were led by highly autocratic leaders, and there remained a lack of respect between police and the community. Following urban unrest in the 1960s, police placed more emphasis on community relations, enacted reforms such as increased diversity in hiring, and many police agencies adopted community policing strategies. In the 1990s, CompStat was developed by the New York Police Department as an information-based system for tracking and mapping crime patterns and trends, and holding police accountable for dealing with crime problems. CompStat has since been replicated in police departments across the United States and around the world, with problem-oriented policing, intelligence-led policing, and other information-led policing strategies also adopted. By countryFrance

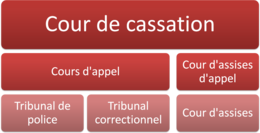

The judicial police in France are responsible for the investigation of criminal offenses and identification of perpetrators.[32][33] This is in contrast to the administrative police, whose goal is to ensure the maintenance of public order and to prevent crime.[32] Article 14 of the French Code of Criminal Procedure provides the legal basis for the authority of the Judicial police.[34][35]  Courts involved in adjudicating questions of French criminal law are organized in three tiers. In the first instance, there are the police court, the correctional court, and the Cour d'assises. The Police court (tribunal de police) hears contraventions (minor infractions like parking tickets).[36] The Criminal court (also known as Correctional court, tribunal correctionnel) hears délits, less serious felonies and misdemeanors.[37] The Court of Assizes sits in each of the departments of France and is normally composed of three judges and six jurors, and has jurisdiction over more serious crimes.[38][39] In the second instance : the Court of appeal, and the Appeal court of assizes. When it sits as a court of appeal, the Court of Assizes is composed of three judges and nine jurors, or seven judges alone.[38][39]See also

References

Works cited

Further reading

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Criminal justice.

|