|

D. Napier & Son

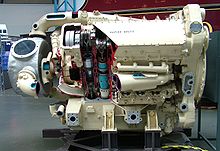

D. Napier & Son Limited was a British engineering company best known for its luxury motor cars in the Edwardian era and for its aero engines throughout the early to mid-20th century. Napier was founded as a precision engineering company in 1808 and for nearly a century produced machinery for the financial, print, and munitions industries. In the early 20th century it moved for a time into internal combustion engines and road vehicles before turning to aero engines. Its powerful Lion dominated the UK market in the 1920s and the Second World War era Sabre produced 3,500 hp (2,600 kW) in its later versions. Many world speed records on land and water, as well as the Hawker Typhoon and Tempest fighter planes, were powered by Napier engines. During the Second World War the company was taken over by English Electric, and engine manufacture eventually ceased. Today, Napier Turbochargers is a subsidiary of the American company Wabtec. HistoryEarly years and precision engineering  David Napier, second son of the blacksmith to the Duke of Argyll, was born in 1785. While cousins became shipbuilders, he took engineering training in Scotland before coming to London. There in 1808 he founded the firm that was to become D. Napier & Son in Lloyds Court, St Giles, London.[1] He designed a steam-powered printing press, some of which went to Hansard (the printer and publisher of proceedings of the Houses of Parliament), as well as newspapers. The company moved to Lambeth, South London, in 1830. Between 1840 and 1860, Napier was prosperous, with a well-outfitted factory and between 200 and 300 workers. Napier made a wide variety of products, including a centrifuge for sugar manufacturing, lathes and drills, ammunition-making equipment for the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, and railway cranes.[2] David's younger son James Murdoch Napier, born 1823, joined the firm in 1837 and became a partner in 1847, resulting in a change in the private company's name to D. Napier & Son.[1] James succeeded his father as head of the firm in 1867, and after his father's death in 1873, specialized in crafted precision machinery for making coins, and printing stamps and banknotes. James proved an excellent engineer, but a poor businessman, considering salesmanship undignified. His company's fortunes went so bad that there were as few as seven employees in 1895, and James attempted to sell the business, but failed.[2][3] Montague Napier and high-performance vehiclesJames' son Montague, born 1870,[2] inherited the business in 1895, along with his father's engineering talents.[2] Montague was a hobby racing cyclist, and at the Bath Road Club, he met "ebullient Australian" S. F. Edge (then a manager at Dunlop Rubber and colleague of H. J. Lawson in London, and amateur racer of motor tricycles.) Edge persuaded Napier to improve his Panhard "Old Number 8" (which had won the 1896 Paris–Marseille–Paris), converting from a tiller to a steering wheel and improving the oiling.[3] Dissatisfied, Napier offered to fit an engine of his own design, an 8 hp vertical twin, with electric ignition, superior to the Panhard's hot tube type.[4] Edge was sufficiently impressed to encourage Napier to make his own car and collaborated with Harvey du Cros, his former boss at Dunlop, to form the Motor Power Company, based in London,[4] which agreed to buy Napier's entire output. The first of an initial order of six, three each two-cylinder 8 hp and four-cylinder 16 hp, all with aluminum bodies by Arthur Mulliner of Northampton and chain drive, was delivered 31 March 1900; Edge paid £400 and sold at £500. In 1903 the manufacturing business moved from Lambeth to larger premises in Acton and in 1906 it became a limited liability company, D. Napier & Son Limited, although it remained in effect a private company for the next few years. Outside the racing programme, Napier also gained fame in 1904 by being the first car to cross the Canadian Rockies: Mr and Mrs Charles Glidden, sponsors of the Glidden Tours, covered 3,536 miles (5,691 km) from Boston to Vancouver.[5] Racing Recognizing the value of publicity gained from racing, which no other British marque did,[6] in spring, Edge entered an 8 hp (6.0 kW) Napier in the Thousand Miles (1,600 km) Trial of the Automobile Club on behalf of Mary Eliza Kennard; driven by Edge, with Kennard along, on a circuit from Newbury to Edinburgh and back, it won its class, being one of only thirty-five finishers (of sixty-four starters[7]) and one of just twelve to average the requisite 12 mph (19 km/h) in England and 10 mph (16 km/h) in Scotland.[8] By June 1900, eight "16 hp"s had been ordered, and Edge entered one in the 837 mi (1,347 km) Paris-Toulouse-Paris race, with Charles S. Rolls (co-founder of Rolls-Royce) as riding mechanic. The 301.6 cu in (4.942 L) (101.6 mm × 152.4 mm, 4.00 in × 6.00 in) sidevalve suffered problems with its ignition coils and cooling system, and failed to finish.[9] For 1901, Montague designed a car sure not to lack speed, having a 990 cubic inches (16.3 L) (165.1 mm × 190.5 mm, 6.50 in × 7.50 in) sidevalve four capable of 103 bhp (77 kW) at 800 rpm, on a wheelbase of 115 inches (2.9 m)[10] with four-speed gearbox and chain drive. Called the "50 hp", only two or three were completed, including one for Rolls.[10] Edge entered one in the 1901 Gordon Bennett Cup, only able to test it en route (it was completed 25 May, only four days before the event), Montague serving as his riding mechanic; it overpowered its Dunlops, and fitting new (French) tyres led to disqualification, since they were not of the same nation of origin.[11] In the concurrent Paris-Bordeaux rally, it retired with clutch trouble.[12] For the 1902 Gordon Bennett, three entrants (the Charron-Girardot-Voigt, a Mors and a Panhard) contested for France, with Edge in a Napier and two Wolseleys. The Napier was a three-speed, shaft-drive 6.44-litre (392.7 cu in) four (127 mm × 127 mm (5.0 in × 5.0 in) of 44.5 hp (33.2 kW) (though described as a 30 hp). Piloted by Edge and his cousin, Cecil, it wore what would become known as British racing green, and won at an average 31.8 mph (51.2 km/h); although by default, since all other entrants retired during the race. It was the first British victory in international motorsport, and would not be repeated until Henry Segrave took the French Grand Prix in 1923.[10]  Napiers also inspired Charles J. Glidden to create the Glidden Tours in upstate New York, which in turn persuaded Napier to build a factory in Boston. It, along with the Genoa factory (managed by Arthur McDonald), which built Napiers under licence as San Giorgios from 1906 to 1909, was not a success.[13] Annual production reached 250 cars in 1903, overwhelming the Lambeth factory, so a move was made to a new 3.75-acre (1.52 ha) plant at Acton, in west London. On 16 October of that year, Napier announced a six-cylinder car for 1904 and became the first manufacturer to make a commercially successful six, a "remarkably smooth and flexible" vehicle[10] 18 hp 301 cu in (4.9-litre) (101.6 mm × 101.6 mm (4.00 in × 4.00 in) with a three-speed gearbox and chain drive.[10] Within five years, there were 62 makers of six-cylinder cars in Britain alone, including the Ford Motor Company's 1906 Model K.[14]  Napier's 1902 win brought the Gordon Bennett hosting duties to the United Kingdom, and the 1903 event was held south of Dublin, with three shaft-driven Napiers defending the British and Irish honour, all in the (later famous) racing green: two 470 cubic inch (7708 cc) 45 hp (34 kW) fours for Charles Jarrott and J. W. Stocks, with McDonald, the Genoa plant manager, his riding mechanic, and an 80-horsepower (838 cubic inch, 13,726 cc), the Type K5, for Edge. Jarrott and Stocks crashed, and Edge was disqualified.[15] It was a bad year for Napier's racing programme; a 35 hp in the hands of Colonel Mark Mayhew in the Paris–Madrid rally lost its steering and hit a tree. Edge, again with McDonald, fared no better with the K5 in the 1904 Gordon Bennett in Germany, but a new 920 cubic inch (15-litre; 158.7 × 127 mm, 6.25 × 5-inch) six, the L48, with an external radiator reminiscent of the Cord 810, set the fastest time at the Velvet Strand speed trials at Portmarnock, Ireland, in September, piloted by McDonald.[16] In January 1905, the L48, again with McDonald in the seat, took the mile (1.6 km) record at Ormonde Beach at 104.65 mph (168.42 km/h); although this was shortly broken by Bowden's Mercedes, the run was disallowed. The versatile McDonald ran the L48 in the 1905 Gordon Bennett qualifying event at the Isle of Man, taken over for the race by works driver Clifford Earp, who placed ninth. Edge's secretary, Dorothy Levitt, drove a 100 hp (75 kW) development of the K5 at the Blackpool and Brighton Speed Trials in 1905, and the next year ran the L48 at the Blackpool Speed Trials, showing talent by equalling Edge's speed and setting a women's record in the flying kilometre of 90.88 mph (146.26 km/h).[10] By 1907, 1200 people were employed by Napier and were making about a hundred cars a year, aided by continuing racing success. Brooklands opened that year, where Napier engineer H. C. Tryon won the first ever event in a 40 hp (30 kW), and Edge made a famous 24-hour run in June, covering 1,581 miles (2,544 km) at an average 65.905 mph (106.064 km/h) in a 60-horsepower 589 cubic inch (9,652 cc) (127 × 127 mm, 5 × 5-inch) six, a record which stood for 18 years.[17] The L48, nicknamed Samson, became famous there in the venue's first two years; in 1908, Napier's Frank Newton covered one-half mile (800 m) at 119.34 mph (192.06 km/h) in a stroked (178 mm, 7-inch) L48.[15] The company's last race win was with a four-cylinder at the 1908 Tourist Trophy, using an alias, Hutton, to preserve the reputation of the sixes, in the hands of Willy Watson.[18] At the French Grand Prix, officials showed the perverse reasoning for which they later became notorious by claiming that removable wire wheels were an unfair advantage.[6] When Napier was no longer in racing, its Lion aero engine was used by several land speed record contestants: Malcolm Campbell's Napier-Campbell Blue Bird of 1927 and Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird of 1931, Segrave's Golden Arrow of 1929, and John Cobb's Napier-Railton and Railton Mobil Special, which held the record from 1939 to 1964.   Motor yachtingNapier expanded into marine engines and launches. In 1903 a S. F. Edge's Napier launch won the inaugural British International Harmsworth Trophy for speedboats at Cork Harbour in Ireland, driven by Dorothy Levitt. She achieved 19.3 mph (31.1 km/h) in a 40-foot (12 m) steel-hulled, speedboat fitted with a 3-blade propeller. As both the owner and entrant of the boat, "S. F. Edge" is engraved on the trophy as the winner. The third crew member, Campbell Muir, may also have taken the controls. On 8 August 1903 Levitt drove the Napier at Cowes and won the race. She was then commanded to the royal yacht by King Edward VII where he congratulated her on her pluck and skill, and they discussed the performance of the boat and its potential for British government despatch work.[19] Later in August Levitt won the Gaston Menier Cup at Trouville, France. This was described as the "five-mile world's championship of the sea" and the prize was $1,750.[20] In October 1903 Levitt won the Championship of the Seas at Trouville, and the French government bought the boat for £1,000.[19][20] The 1905 boat Napier II set the world water speed record for a mile at almost 30 knots (56 km/h). Public limited company and WWI In 1912, following a dispute with Edge, the business was restructured. D. Napier & Son Limited went public and bought out Edge's distribution and sales company, S.F. Edge (1907) Limited. The latter soon went into voluntary liquidation and thus the manufacture and marketing of Napier cars were united under a single organization.[1] Production rose to around 700 cars a year with many supplied to the London taxi trade. That year, only six models were produced. On the outbreak of war sales of private vehicles collapsed and Napier turned to military orders. Vehicle production continued for a time on this basis and 2,000 trucks and ambulances were supplied to the War Office. Montague Napier's health declined and in 1917 he moved to Cannes, France, but continued to take an active involvement in the company until his death in 1931. Early in the war, Napier was contracted to build engines from other companies' designs: initially the model RAF 3, a V-12 by Royal Aircraft Factory, and then the V-8 Sunbeam Arab. Both proved to be rather unreliable, and in 1916 Napier decided to design its own instead, an effort that led to the superb W-block 12-cylinder Lion.[21] The Lion came into service shortly before the end of the war. During the First World War the company was also contracted to build 600 aircraft at the Acton factory (50 Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.7, 400 Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.8 and 150 Sopwith Snipes). Together with the engine work, this required enormous expansion of the company. Interwar period By the end of the war, military production had tailed off and the Lion was still barely in use. In 1919 civilian car production was recommenced. The T75 motor car would be Napier's last. Designed by A. J. Rowledge (who left for Rolls-Royce in 1921), its engine was a 40–50 hp 377 cu in (6,178 cc) (101.6 mm × 127 mm or 4.00 in × 5.00 in) alloy six with detachable cylinder head, single overhead camshaft, seven-bearing crankshaft, dual magneto and coil ignition, dual plugs, and Napier-SU Carburettor. Coachwork was by Cunard, by then a subsidiary.[4] 187 were built in all by 1924, and Napier quit car production with a total of 4,258 built.[4] The car was very expensive, costing about the same as a Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost and in the early 1920s sales were slow. The last car was sold in 1924. The Lion was by now becoming a best-seller for the company, which eventually dropped all the other aero-engines. The Lion went on to be adapted for land and water, to set the land speed record in Malcolm Campbell's Napier-Campbell Blue Bird of 1927 and Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird of 1931 and Henry Segrave's Golden Arrow of 1931 and later in John Cobb's Napier-Railton and Railton Mobil Special, which held the record from 1939 to 1964. In the 1930s the introduction of much larger and more powerful aero-engines from other companies ended sales of the Lion. Napier quickly started work on newer designs, building on experience gained on the X style 16-cylinder, 1,000 horsepower (750 kilowatts) Cub, used in the Blackburn Cubaroo single-engined bomber of the 1920s, and the resulting later 16-cylinder Rapier and 24-cylinder Dagger were both air-cooled H-block designs. Neither the Rapier nor the Dagger proved very reliable, due to poor cooling of the rearmost cylinders, and even the Dagger's 1,000 hp (750 kW) was less than its competitors' offerings when shipped.[citation needed] As Lion sales faded, an attempt was also made to buy the bankrupt Bentley company in 1931 but Napier was outbid at the last minute by Rolls-Royce. The last vehicle project was a three-wheeled tractor-trailer goods vehicle, but rather than produce this itself, the design was sold to Scammell, which made several thousand. Second World War Starting from scratch, Napier decided to use the new sleeve valve design in a much larger H-block 24-cylinder engine, soon to be known as the Sabre. Designed under Frank Halford, the engine was very advanced and proved to be difficult to adapt to assembly line production. Therefore, although the engine was ready by 1940, it was not until 1944 that production versions were considered reliable. At that point efforts were made to improve it, leading eventually to the Sabre VII delivering 3,500 hp (2,600 kW), making it the most powerful engine in the world, from an engine much smaller than its competition. Napier also worked on diesel aircraft engines. In the 1930s it licensed the Junkers Jumo 204 for production in England, which it called the Culverin. It also planned to produce a smaller version of the same basic design as the Cutlass, but work on both was cancelled at the outbreak of war in 1939. Napier developed a marine engine from the Lion aero engine, the petrol-driven Sea Lion, which could deliver 500 hp (370 kW) and was used in the "Whaleback" Air Sea Rescue Launches.  During the war (1944) Napier was asked by the Royal Navy to supply a diesel engine for use in its patrol boats, but the Culverin's 720 hp (540 kW) was not nearly enough for its needs. Napier then designed under the leadership of Ernest Edward Chatterton, Chief Engineer, the Deltic, essentially three Culverins arranged in a large triangle. Considered one of the most complex engine designs of its day, the Deltic was nevertheless very reliable, and was taken into service after the war as a locomotive powerplant (in British Rail's Class 55) in addition to the torpedo boats, minesweepers and other small naval vessels for which it was designed. Also during the Second World War a six-cylinder 300 cubic inch road-vehicle engine was commissioned by the government, but this design was sold to Leyland Motors by 1945. Post-warEnglish ElectricNapier had been taken over by English Electric on 23 November 1942.[22] Last of the great Napier internal combustion engines was the Nomad, a complex "turbo-compound" design that combined a diesel engine with a turbine to recover energy otherwise lost in the exhaust. The advantage of this complex design was fuel economy: it had the best specific fuel consumption of any aircraft engine, even to this day. However, even better fuel economy could be had by flying a normal jet engine at much higher altitudes, while existing designs filled the "low end" of the market fairly well. First run in 1949, the Nomad I underwent radical redesign for the Nomad II but was largely ignored by the market and was cancelled in 1955. Along with every major aero engine company in the post-war era, Napier turned to the jet turbine. Seeing a niche not yet adopted up by the larger vendors, Napier developed a number of turboshaft designs which saw some use, notably in helicopters. Its first design, the Naiad and Double Naiad was developed for various Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm projects, but did not enter production. The smaller models developed later, the 3,000-hp-class Eland and 1,500-hp-class Gazelle did somewhat better, notably the Gazelle which powered several models of the popular Westland Wessex helicopter. Production ceased when a deal was struck with Rolls-Royce in 1961. At the same time, the ramjet was showing promise for high-speed supersonic flight. From 1951 Napier developed a successful large-diameter experimental engine, the Napier Ram Jet (NRJ). Napier continued in ramjet development for several years, typically working alongside the English Electric aircraft design team.[23] Napier Aero Engines LimitedIn 1961 a new company Napier Aero Engines Limited was formed by D. Napier & Son and Rolls-Royce, to take over the Napier aero-engine business and the Acton engine factory.[24] It was to continue to market the Gazelle, while the completion of existing Gazelle contracts and the Eland remained the financial responsibility of the old company. But it closed only two years later, in 1963.[25] Following the move of the aero engine business, D. Napier & Son continued as a subsidiary of English Electric.[24] With the ending of Deltic sales in the 1960s it had no new modern engine designs to offer. Today Napier is no longer in the engine business. Napier TurbochargersGEC bought English Electric in the late 1960s. The GEC operation, now part of Ruston Gas Turbines, later moved to GEC-Alsthom and then Alstom, before being sold to Siemens in March 2003. Napier Turbochargers was bought from Siemens in June 2008 in a management buyout. The buyout was funded by the private equity company Primary Capital for around £100 million.[26][27] Early in 2013 Napier Turbochargers became part of Wabtec. Napier Turbochargers currently produces turbochargers for the marine, power, and rail industries, employing around 150 people. List of Napier aero enginesThese engines were all built, some in several variants.[28][29]

See alsoReferencesNotes

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Napier & Son aircraft engines. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Napier & Son engines. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Napier vehicles. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Napier-Railton. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Napier-Bentley. |