|

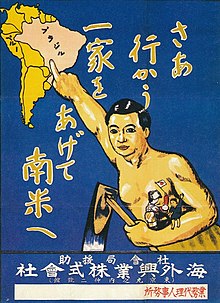

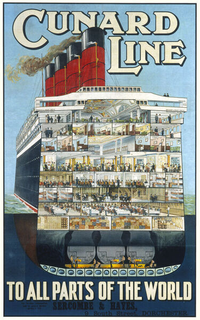

EmigrationEmigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence[1] with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country).[2] Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanently move to a country).[3] A migrant emigrates from their old country, and immigrates to their new country. Thus, both emigration and immigration describe migration, but from different countries' perspectives.  Demographers examine push and pull factors for people to be pushed out of one place and attracted to another. There can be a desire to escape negative circumstances such as shortages of land or jobs, or unfair treatment. People can be pulled to the opportunities available elsewhere. Fleeing from oppressive conditions, being a refugee and seeking asylum to get refugee status in a foreign country, may lead to permanent emigration. Forced displacement refers to groups that are forced to abandon their native country, such as by enforced population transfer or the threat of ethnic cleansing. Refugees and asylum seekers in this sense are the most marginalized extreme cases of migration,[4] facing multiple hurdles in their journey and efforts to integrate into the new settings.[5] Scholars in this sense have called for cross-sector engagement from businesses, non-governmental organizations, educational institutions, and other stakeholders within the receiving communities.[6][7] HistoryPatterns of emigration have been shaped by numerous economic, social, and political changes throughout the world in the last few hundred years. For instance, millions of individuals fled poverty, violence, and political turmoil in Europe to settle in the Americas and Oceania during the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. Likewise, millions left South China in the Chinese diaspora during the 19th and early 20th centuries.  "Push" and "pull" factorsDemographers distinguish factors at the origin that push people out, versus those at the destination that pull them in.[8] Motives to migrate can be either incentives attracting people away, known as pull factors, or circumstances encouraging a person to leave. Diversity of push and pull factors inform management scholarship in their efforts to understand migrant movement.[9][4] Push factors

Pull factors

CriticismSome scholars criticize the "push-pull" approach to understanding international migration.[10] Regarding lists of positive or negative factors about a place, Jose C. Moya writes "one could easily compile similar lists for periods and places where no migration took place."[11] Emigration waves by countrySearch for "Emigration from" in titles

StatisticsUnlike immigration, in many countries few if any records have been recorded[a] or maintained in regard to persons leaving a country either on a temporary or permanent basis. Therefore, estimates on emigration must be derived from secondary sources such as immigration records of the receiving country or records from other administrative agencies.[14] The rate of emigration has continued to grow, reaching 280 million in 2017.[15] In Armenia, for example, the migration is calculated by counting people arriving or leaving the country via airplane, train, railway or other means of transportation. Here, the emigration index is high: 1.5% of population leaves the country annually.[16] In fact, it is one of the countries, where emigration has become a part of culture since 20th century. For example, between 1990 and 2005 approximately 700,000–1,300,000 Armenians left the country. The highly rising numbers of emigration are a direct response to socio-political and economic areas of the country. The internal migration (migration in country) is big (28.7%), while international migration is 71.3% of the total migration by people aging 15 and above. It is important to understand the reasons for both types of migration and the availability of the options. For example, in Armenia, everything is localized in the capital city Yerevan, thus, internal migration is from the villages and small cities to the biggest city of the country. The reason for the migration can be work or study. International migration follows the same reasoning of migration: work or study. The main destinations for it are Russia, France and US.[17] Emigration restrictions Some countries restrict the ability of their citizens to emigrate to other countries. After 1668, the Qing Emperor banned Han Chinese migration to Manchuria. In 1681, the emperor ordered construction of the Willow Palisade, a barrier beyond which the Chinese were prohibited from encroaching on Manchu and Mongol lands.[18] The Soviet Socialist Republics of the later Soviet Union began such restrictions in 1918, with laws and borders tightening until even illegal emigration was nearly impossible by 1928.[19] To strengthen this, they set up internal passport controls and individual city Propiska ("place of residence") permits, along with internal freedom of movement restrictions often called the 101st kilometre, rules which greatly restricted mobility within even small areas.[20] At the end of World War II in 1945, the Soviet Union occupied several Central European countries, together called the Eastern Bloc, with the majority of those living in the newly acquired areas aspiring to independence and wanted the Soviets to leave.[21] Before 1950, over 15 million people emigrated from the Soviet-occupied eastern European countries and immigrated into the west in the five years immediately following World War II.[22] By the early 1950s, the Soviet approach to controlling national movement was emulated by most of the rest of the Eastern Bloc.[23] Restrictions implemented in the Eastern Bloc stopped most east–west migration, with only 13.3 million migrations westward between 1950 and 1990.[24] However, hundreds of thousands of East Germans annually immigrated to West Germany through a "loophole" in the system that existed between East and West Berlin, where the four occupying World War II powers governed movement.[25] The emigration resulted in massive "brain drain" from East Germany to West Germany of younger educated professionals, such that nearly 20% of East Germany's population had migrated to West Germany by 1961.[26] In 1961, East Germany erected a barbed-wire barrier that would eventually be expanded through construction into the Berlin Wall, effectively closing the loophole.[27] In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, followed by German reunification and within two years the dissolution of the Soviet Union. By the early 1950s, the Soviet approach to controlling international movement was also emulated by China, Mongolia, and North Korea.[23] North Korea still tightly restricts emigration, and maintains one of the strictest emigration bans in the world,[28] although some North Koreans still manage to illegally emigrate to China.[29] Other countries with tight emigration restrictions at one time or another included Angola, Egypt,[30] Ethiopia, Mozambique, Somalia, Afghanistan, Burma, Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia from 1975 to 1979), Laos, North Vietnam, Iraq, South Yemen and Cuba.[31] See also

NotesReferences

Further readingLook up emigration in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

External linksLook up emigration in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

|