|

Emory Johnson

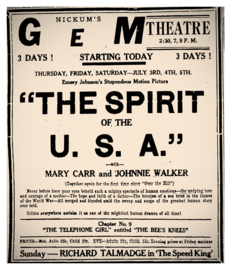

Alfred Emory Johnson (March 16, 1894 – April 18, 1960) was an American actor, director, producer, and writer. As a teenager, he started acting in silent films. Early in his career, Carl Laemmle chose Emory to become a Universal Studio leading man. He also became part of one of the early Hollywood celebrity marriages when he wed Ella Hall. In 1922, Emory acted and directed his first feature film – In the Name of The Law. He would continue to direct more feature films until the decade's end. By the early 1930s, his Hollywood career had faded, and Johnson became a portrait photographer. In 1960, he died from burns sustained in a fire. Early yearsEmory Johnson was the son of Swedish immigrants. Johnson's father, Alfred (Alf) Jönsson, was born in Veinge, Halland, Sweden, on February 7, 1864.[1] In 1884, his father emigrated to America when he was 20. After his arrival, Jönsson anglicized his name to Johnson. Johnson's mother, Emilie Mathilda Jönsdotter, was born in Gothenburg, Västra Götaland, Sweden, on June 3, 1867.[2] At age 24, Emilie Jönsdotter departed for America and reached Ellis Island in New York Harbor, on September 24, 1891.[3] While Emilie Jönsdotter was living in San Francisco, she met Alfred Johnson. Following a brief romance, they exchanged vows at the Ebenezer Lutheran Church in San Francisco, California, on May 11, 1893. Their only son, Alfred Emory Johnson, was born in San Francisco on March 16, 1894.[4] According to the 1900 census, the Johnson family rented a large house on Bush Street in San Francisco, California.[5] The same census listed Emory's father as a "Keeper of Turkish bath.[5] On Wednesday, April 18, 1906, San Francisco suffered a major earthquake. In the quake's aftermath, fires broke out, destroying 80% of the city and resulting in 3,000 deaths. The Turkish bath, managed by Alf Johnson, was destroyed. Following the quake, the Johnson family moved to nearby Alameda, California in 1908.[6] Emory's father established the Piedmont Baths in 1910 to provide for the family.[7] Johnson attended Oakland High School, then studied architecture at the University of California, Berkeley. After spending a year and a half in college, he quit his studies and searched for employment. Johnson would later say, "I just got tired of pushing a slide rule around."[8] CareerEssanay years In 1912, 18-year-old Johnson began a motorcar journey through the picturesque Niles Canyon in the San Francisco Bay Area. While driving, he heard noises that sounded like gunshots. Out of nowhere, "a gang of cowboys rode up, shooting at a stagecoach."[8] As events unfolded, he encountered a film crew shooting a Western movie. The Essanay Studios, based in Niles, was creating one of their famous Broncho Billy westerns. These early Essanay Westerns showcased the first cowboy star of the silver screen, Gilbert Anderson. Future Western stars were forever indebted to this "motion picture pioneer."[9] During that period, Essanay Studios was co-owned by Anderson and George Kirke Spoor.[10][11] Emory became captivated by the Film industry. He began hanging around the film crews, offering to do odd jobs. Eventually, Gilbert Anderson noticed Johnson. In September 1912, Anderson offered to give the 18-year-old an entry-level job as an assistant cameraman, paying $8.50 per week (equivalent to $258 in 2022 or $13,400 yr). His new job allowed him to learn about the movie business from the ground up.[8][12] Johnson operated in that capacity until September 1913, when he signed his first movie contract with Essanay. He appeared in his first film, "Hard Luck Bill" as an uncredited extra. Johnson was 19 when this film came out on September 13, 1913. He made three more Western short films in 1913. Johnson, now Essanay's latest "most handsome actor,"[13] received his first movie credit on "What Came to Bar Q" in January 1914 when he was 19 years old. Johnson started landing more crucial roles in Essanay Westerns.[12] He marked his first top billing in a short drama, "Italian Love," released on February 19, 1914. Later, he earned another top billing in a short comedy, "The Warning." released on March 12, 1914. He landed roles in the Snakeville comedy series and the Sophie series of comedies. In 1914, Johnson made nineteen short films for Essanay. 1914 became the highest movie output of Johnson's entire career. The last film Johnson, now 20, made for Essanay, was the short Western, "Broncho Billy's Jealousy" released on June 27, 1914. Emory Johnson worked for Essanay for two years, from 1912 through 1914. Johnson's rapid ascent at Essanay was achieved in ten months, from September 1913 until June 1914. Johnson acted in 23 short films for Essanay, including nine Broncho Billy Westerns. However, Essanay relied on producing short films, but this dependence had consequences. Moviegoers requested feature-length movies, and Essanay lacked the resources to produce these types of films. The bottom line is that Essanay was losing money. In late 1914 and early 1915, Essanay hemorrhaged talent, including Marguerite Clayton, Carl Stockdale, Emory Johnson, Vera Hewitt, True Boardman, and Virginia True Boardman. The Liberty Film Company in San Mateo hired many actors and actresses who quit Essanay.[14] The main factors fueling the talent exit were Essanay's inability to produce feature-length movies and the company's decline in revenue. Following a short pause in 1915, the Niles Essanay studio closed its doors on February 16, 1916.[15] The Liberty Film CompanyEmory's last film for Essanay was released in June 1914. There would be a year's lapse before releasing his next movie. In 1915, Emory turned 21 and invested in his own motion picture company – Liberty Motion Picture Company. Liberty Film Company was formed in June 1914 and is based in Germantown, Pennsylvania. The company was reorganized in November 1914. The new owners relocated the offices and lots to San Mateo and Glendale, California. The Alaskan Millionaires that purchased the company had plenty of cash and state-of-the-art facilities. Emory jumped from Essanay to Liberty films. Because of his late start, Emory's film output dropped substantially. Emory made only four motion pictures in 1915. His first was His Masterpiece, a two-reeler released in September 1915, and another two-reeler would follow – Her Devoted Son (Several alternative listings show Devoted Son). In the waning months of 1915, he acted in his last two films for Liberty. He would share top billing with Marguerite Clayton for making the feature films – The Birthmark and The Black Heart. Both films were Dramas. By December 1915, Emory had left Liberty. In December 1915, a receiver was appointed. Liberty burned to the ground in 1916.[16][17] Universal yearsIn January 1916, Emory signed a contract with Universal Film Manufacturing Company. He would make 17 movies that year, including six shorts and 11 feature-length Dramas. This year would become the second-highest movie output of his entire acting career. At Universal, Emory met Hobart Bosworth. Hobart Bosworth was a well-known actor and director. He took young Emory under his wing.[8] Emory's first two movies for Universal were the Westerns – The Yaqui and Two Men of Sandy Bar. Both films were feature-length and starred Hobart Bosworth. Later in the year, Emory would make two more films with Hobart. They would continue collaborating in other films in the coming years, including the last film Emory would direct. The film was the 1932 talkie The Phantom Express.

In early 1916, after Emory Johnson had signed his Universal contract, Carl Laemmle of Universal Film Manufacturing Company thought he saw a potential leading man in Johnson. Laemmle sought a leading man comparable to Wally Reid. He also hoped to create a movie couple that could make sparks fly on the silver screen. Laemmle chose Johnson to be his new leading man. Laemmle chose Dorothy Davenport to generate the screen chemistry with Johnson. She was a Universal contract player who happened to be the wife of Wally Reid. Johnson and Davenport made 13 films together. The series started with the feature production of Doctor Neighbor in May 1916 and ended with another feature production, The Devil's Bondwoman, in November 1916. Over half the films were feature-length; all were dramas. Johnson and Davenport shared top billing in most. Davenport got pregnant in October 1916, and her film output took a steep nosedive at the beginning of 1917.[18] Ultimately, Laemmle thought Johnson did not have the talent or screen presence he wanted. He wasn't going to become Universal's answer to Wally Reid. Laemmle also believed that even though the pairing with Davenport had been financially successful, the films didn't have the screen chemistry he had sought.[19][18]

In March 1917, Emory Johnson turned 23 years old. He completes his WWI draft registration but claims exception due to a "Nervous heart" and "Chronic stomach trouble."[33] His 1917 film output drops to 4 pictures. He made "The Gift Girl" released in March 1917. He puts three more in the can before June 1917. At the end of 1917, Emory and Ella Hall were cast together playing husband and wife in – "My Little Boy" The film was released in December 1917. They would make three more films together in 1918, including their last Universal film – "A Mothers Secret," released in April 1918. In June 1918, Universal failed to renew the contracts of Ella Hall and Emory Johnson. The news was a minor announcement buried deep in the Hollywood trade newspapers.[34] In reality, Laemmle thought Emory did not have the talent or screen presence he wanted. He wasn't going to become Universal's answer to Wally Reid. After all, Wally Reid was well on his way to becoming "The screen's most perfect lover."[35] Ella Hall was pregnant with their first child at their release. The last movie the couple filmed together also became Emory's last movie for Universal – A Mother's Secret. Ella's last movie for Universal was Three Mounted Men released in October 1918. Emory made 27 films for Universal, mostly dramas with a sprinkling of comedies and Westerns. Independent yearsAs explained previously, Emory's Universal contract ended in May 1918. Thus, in 1918, 24-year-old Emory Johnson became a free agent. He could now pick and choose his projects. Emory's first movie was released in August 1918. The movie was – Green Eyes with Dorothy Dalton. Next would follow the very successful Johanna Enlists with Mary Pickford. Then A Lady's Name with Constance Talmadge followed by The Ghost Flower with Alma Rubens. In 1919, Emory acted in seven movies, including The Woman Next Door with Ethel Clayton. Emory ended 1919 with a role in the successful Alias Mike Moran featuring Wallace Reid and Ann Little. In 1920, Emory acted in five films, including Polly of the Storm Country, sharing top billing with Mildred Harris. Emory's film output for 1921 would be two films. In January 1921, he acted in Prisoners of Love starring Betty Compson. Finally, the successful The Sea Lion was released in December 1921. Emory shared top billing with Hobart Bosworth and Bessie Love.[36][37] It is noteworthy, the writing credit for the movie was his mother, Emilie Johnson. The movie credit would become Emilie's second writing credit after Blind Hearts. Between June 1918 and June 1922, Emory bounced between 14 production companies, including Pickford Films, Chaplin-Mayer Picture Company, Famous Players–Lasky, and Betty Compson Productions. Emory also acted with and often shared top billing with the following leading ladies: Marguerite Clayton, Dorothy Davenport, Louise Lovely, Mary Pickford, Constance Talmadge, Ethel Clayton, Margarita Fischer, Mildred Harris, Ella Hall, Eileen Percy, Bebe Daniels, Bessie Love and Betty Compson. Directorial years1922 - 1925Emory made the equivalent of indie films in the 1920s. 1922 proved to be a watershed year, creatively and financially. First, the independent actor started the year with a March release of Don't Doubt Your Wife, sharing top billing with Leah Baird. In July, Always the Woman starring Betty Compson was released. Now the year would head in a different direction. A 28-year-old actor with no directing experience convinced a studio to let him direct and produce a melodrama written by his mother about a San Francisco beat cop. Emilie and her son had initially contracted with Robertson-Cole to write, produce and direct The Midnight Call. Then R-C was acquired by FBO. On July 1, 1922, the Robertson-Cole (R-C) Distribution company became known as FBO. All R-C contracts were honored, especially with independent producers like Emory Johnson.[38] The first Johnson collaboration under the renamed FBO contract was The Midnight Call. The film's title transformed into In the Name of the Law. The film was released in August 1922—credit Emilie Johnson for the story and screenplay for this melodrama. The story is about a San Francisco policeman trying to keep his family together while facing continuing adversity.[39] When the movie finished, it laid the first building block toward attaining the title of "Hero of the Working Class." This wasn't the only reason FBO released the movie. They saw tremendous potential for exploitation. Making a movie about the working class opened itself to exploitation. Thus, Emory also cemented his reputation towards becoming the "King of Exploitation."[40] The hit led to the next Emory Johnson file – The Third Alarm. In December, FBO released The Third Alarm formerly titled The Discard. This film is the second under the FBO contract. Emory directed this Emilie Johnson story.[41] The film would become the most financially successful movie produced in Emory Johnson's career. The movie earned Emory $275,000 (equivalent to $4,807,853 in 2022).[8] In 1923, Johnson finished the third film in his FBO contract, The West~Bound Limited. Emilie Johnson wrote both the story and screenplay for this Emory Johnson film. The film earned $225,697 (equivalent to $3,945,884 in 2022).[8][42][43] The fourth film in the FBO contract was The Mailman. Once again, Emilie Johnson wrote both the story and the screenplay. Emory earned This movie earned Emory $179,476 (equivalent to $3,137,797 in 2022).[8][44] The mailman epitomizes an over-the-top melodrama and displays Emilie's flair for this genre.[45] In September, Emilie and Emory Johnson signed a new contract with FBO. The contract was for 2.5 years. Emory Johnson agreed to make eight attractions for FBO, including the previous four he had completed. FBO agreed to invest upwards of 2.5 million dollars (equivalent to $42,939,453 in 2022) on future productions.[46] Another part of the signed contract stipulated – "The contract also provides that Emory Johnson's mother, Mrs. Emilie Johnson, shall prepare all of the stories and write all the scripts for the Johnson attractions in addition to assisting her son in filming the productions."[46] 1924 started with Johnson's fifth film for FBO – The Spirit of the USA. The film was released in May. Emilie wrote both the story and the screenplay.[47][48][49] Emory finished the year with the sixth film under the FBO contract – the September release of Life's Greatest Game. Emilie Johnson had created a story about America's favorite pastime – baseball.[50] In 1925, Johnson fcomplete his seventh film for the FBO, The Last Edition, released in October. This movie was Johnson's "last hurrah" for the working man series of movies.[51][52] 1926 - 1932In March 1926, Johnson released his last picture for FBO – The Non-Stop Flight.[53][54] Emory and Emilie were then working on a movie titled Happiness. Work had supposedly started in December 1925. Emory, Emilie, and the cast and crew had sailed for Sweden to film the movie. The fate of the movie remains unknown.[55] In April, FBO decided to let Emory and Emilie Johnson's contracts expire; there is no published reason for this.[56] In June, Emory Johnson signed a new eight-picture deal with Universal.[57] Johnson also suffered a major tragedy. Emory and Ella's son were run over by a truck in Los Angeles. Alfred Bernard Johnson was only five years old when he died in March 1926. The couple was not living together at the time of his death. His death devastated both parents.[58] In 1927, Johnson, now filming under his new Universal contact, released The Fourth Commandment.[59] In September, he released The Lone Eagle.[60][61] This movie title is confusing, maybe even misleading. A film title cannot be protected by copyright.[62] In May 1927, Charles A. Lindberg completed his solo flight across the Atlantic. He acquired the nickname "The Lone Eagle." The Johnson movie The Lone Eagle was initially titled War Eagles. The copyright office got involved and forced Universal to change its name. In February 1928, Johnson released The Shield of Honor.[63][64] After completing three successful movies for Universal, Johnson reneged on the remainder of his eight-picture contract. He negotiates a new contract with Poverty Row studio, Tiffany-Stahl Productions.[65][66] Tiffany-Stahl Productions was more than happy to sign Johnson. They knew his films always made a profit and that the Johnson brand on the marquee drew paying customers. 1929 was not productive for Johnson. He spent significant portions of 1929 trying to reunite with Ella Hall to repair their marriage. Because they had lost their son, Alfred Bernard, in 1926, Emory and Ella decided to have one last child. Emory's daughter, Diana Marie (Dinie), was born in October 1929.[67] In November 1930, Emory Johnson released his first Tiffany-Stahl Productions contract production, The Third Alarm. Although its name was the same as the 1922 version, the similarity ended there. As the quote below shows, T–S was trying to capitalize on the popular 1922 film's name recognition. This film would become Johnson's first talkie.[68] A significant news item appeared in a 1930 issue of Variety magazine.

Emory reneges on the remainder of his Tiffany contract and signs a new contract with Poverty Row studio – Majestic Pictures. Note – Tiffany-Stahl Productions filed for bankruptcy in 1932. In 1932, Johnson had new contract in hand, and released his first movie for Majestic Pictures – The Phantom Express. It would become the last movie he would ever direct. It was the final curtain call for Emory's independent directing years and his mother's collaborative writing.[70][71] Emory was contracted to make one last picture for Majestic Pictures – Air Patrol, but the project never came to fruition.[72] End of an eraThe movies Emory Johnson's completed or planned to start for poverty row studios had one common thread—the would-be remakes of previous successful silent films. For example, the 1930 version of The Third Alarm was supposed to be an updated version of the highly successful 1922 The Third Alarm. The new version would also be a Talkie. Using the same criteria, the 1932 film – The Phantom Express. This Talkie would be a remake of the moderately successful The West~Bound Limited. Even the canceled film – Air Patrol was supposed to be an updated sound version of The Shield of Honor.[73] Post HollywoodIn the March 8, 1932 issue of Variety, a minor item on page 10 read:[74]

Perhaps one factor leading to this bankruptcy could be an attempt to reduce the financial obligations towards Ella and the children. Emory's mother, Emilie, died in Los Angeles, California, on September 23, 1941. She was 75. In 1944, Emory moved from Los Angeles to San Mateo, California. He established a photo portrait studio in the area – Portraits by Emory. The studio would close in 1950. Marriage, children and divorceElla Hall with 3 children Oct 1924 (AI upscaled image) Ella Hall with 3 children Jul 1924 (AI upscaled image) On June 13, 1917, the President of Universal Film Manufacturing Company – Carl Laemmle, held a gala for his employees. He had spent considerable time managing the affairs at Universal City in California. Now, he was about to return to his headquarters in New York. "The occasion promised to be one of the most noteworthy in the history of film functions." Three thousand guests showed up, including Emory Johnson.[75][76] Emory, 23, attended the ball escorting another fellow universalite – Ella Hall. Ella Hall, 20 years old, was an American actress. Emory and Hall starred together in the 1916 film My Little Boy. The movie was the first film with Hall. They began their relationship during the making of the film. The couple announced their engagement during the Laemmle ball.[77] After finishing work at Universal, Emory and Hall got married in a private ceremony September 6, 1917. After the ceremony, they went on their honeymoon. They were scheduled to return to work on October 1.[78][79] After the honeymoon was over, the couple moved into Emory's house along with Johnson's mother Emilie Johnson.  Their first son (Richard) Walter Emory, was born on January 27, 1919, in Santa Barbara, California. Their second son Bernard Alfred was born on September 26, 1920, in Santa Barbara, California. Their daughter Ellen Joanna was born in Los Angeles, California, on April 18, 1923. In 1924, Emory and Hall had their first separation. Ella cited the main problem was the conflict between her and Emory's overbearing mother. Ella filed for divorce. March 1926, Hall was walking down a street in Hollywood with her Children. Bernard was run over and killed by a truck driver.[58] A second separation occurred in 1929. Later that year, the couple decided to have another child. Diana Marie (Dinie) was born in Los Angeles, California, on October 27, 1929. She would be their last child together.

Ella Hall

September 1931[80] From 1924 onwards, the couple had engaged in highly publicized disputes revolving around alimony payments, child support, visitation rights, and living arrangements. Their relationship was also characterized by a constant cycle of breaking up and getting back together. Ella had difficulty reconciling her emotions regarding Emory's status as an only child and what she perceived as his excessive attachment to his mother. She viewed Emory as a "mother's boy," suggesting that his close bond with his mother interfered with their relationship. She believed that the presence and influence of her mother-in-law in their daily lives went beyond what she considered acceptable. Ella succinctly captured her frustration with the statement, "Too much mother-in-law!" In 1930, their stormy relationship came to an end. The divorce between Alfred Emory Johnson, 36, and Ella Augusta Hall, 34, was finalized in Los Angeles, California. At one time, they were considered one of Hollywood's ideal marriages. After the divorce, they would continue to battle over money. Neither would ever remarry.[80] DeathOn Wednesday, March 16, 1960, Emory Johnson turned 66. Now partially disabled, Emory supported himself with Social Security and small pension checks. He rented a first-floor studio in a rooming house on North Ellsworth Street in San Mateo, California.[81] Shortly after 8 pm on Wednesday, March 30, 1960, a neighbor living directly above Emory's first-floor studio smelled smoke. He rushed downstairs, entered the smoke-filled apartment, found a badly-burned Emory, and dragged him to the walkway outside. Firemen responding to the alarm spotted him lying on the ground and called an ambulance. They rushed him to San Mateo Community Hospital in critical condition. Emory Johnson suffered 2nd, and 3rd degree burns over a third of his body. The fire inspector later noticed cigarettes and matches scattered throughout the apartment. It was determined the fire had probably started in some bed clothing and had been burning for a half-hour before the neighbor entered his apartment.[81] Emory lingered in the hospital until Monday, April 18, when he died of burns from the fire.[82] Even though he was 30 years removed from his Hollywood glory years, his death was still front-page news in the San Mateo Times.[83] Emory Johnson chose interment in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Daisy Columbarium, located in Glendale, California. In 1981, his ex-wife Ella Hall died and was laid to rest in Forest Lawn's Columbarium of Sunlight. His only surviving son died in 1994. When his two daughters died, they chose interment next to their mother. The bronze marker on Emory Johnson's Forest Lawn mausoleum niche reads "JOHNSON."[84] Filmography

Gallery

References

Bibliography

Links to surviving films

See alsoExternal links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||