|

Environmental issues in the United States

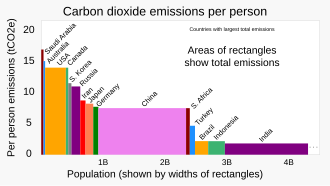

Environmental issues in the United States include climate change, energy, species conservation, invasive species, deforestation, mining, nuclear accidents, pesticides, pollution, waste and over-population. Despite taking hundreds of measures, the rate of environmental issues is increasing rapidly instead of reducing. The United States is among the most significant emitters of greenhouse gasses in the world. In terms of both total and per capita emissions, it is among the largest contributors.[2] The climate policy of the United States has a major influence on the world.[3][4] Movements and ideas20th centuryBoth conservationism and environmentalism appeared in political debate in forests about the Progressive Era in the early 20th century. There were three main positions. The laissez-faire position held that owners of private property—including lumber and mining companies—should be allowed to do anything they wished for their property.[5] The Conservationists, led by President Theodore Roosevelt and his close ally Gifford Pinchot, said that the laissez-faire approach was too wasteful and inefficient. In any case, they noted, most of the natural resources in the western states were already owned by the federal government. The best course of action, they argued, was a long-term plan devised by national experts to maximize the long-term economic benefits of natural resources. Environmentalism was the third position, led by John Muir (1838–1914). Muir's passion for nature made him the most influential American environmentalist. Muir preached that nature was sacred and humans are intruders who should look but not develop. He founded the Sierra Club and remains an icon of the environmentalist movement. He was primarily responsible for defining the environmentalist position, in the debate between Conservation and environmentalism. Environmentalism preached that nature was almost sacred, and that man was an intruder. It allowed for limited tourism (such as hiking), but opposed automobiles in national parks. It strenuously opposed timber cutting on most public lands, and vehemently denounced the dams that Roosevelt supported for water supplies, electricity and flood control. Especially controversial was the Hetch Hetchy dam in Yosemite National Park, which Roosevelt approved, and which supplies the water supply of San Francisco. Climate change  Climate change has led to the United States warming by 2.6 °F (1.4 °C) since 1970.[8] The climate of the United States is shifting in ways that are widespread and varied between regions.[9][10] From 2010 to 2019, the United States experienced its hottest decade on record.[11] Extreme weather events, invasive species, floods and droughts are increasing.[12][13][14] Climate change's impacts on tropical cyclones and sea level rise also affect regions of the country. Cumulatively since 1850, the U.S. has emitted a larger share than any country of the greenhouse gases causing current climate change, with some 20% of the global total of carbon dioxide alone.[15] Current US emissions per person are among the largest in the world.[16] Various state and federal climate change policies have been introduced, and the US has ratified the Paris Agreement despite temporarily withdrawing. In 2021, the country set a target of halving its annual greenhouse gas emissions by 2030,[17] however oil and gas companies still get tax breaks.[18] Climate change is having considerable impacts on the environment and society of the United States. This includes implications for agriculture, the economy (especially the affordability and availability of insurance), human health, and indigenous peoples, and it is seen as a national security threat.[19] US States that emit more carbon dioxide per person and introduce policies to oppose climate action are generally experiencing greater impacts.[20][21] 2020 was a historic year for billion-dollar weather and climate disasters in U.S.[22] Although historically a non-partisan issue, climate change has become controversial and politically divisive in the country in recent decades. Oil companies have known since the 1970s that burning oil and gas could cause global warming but nevertheless funded deniers for years.[23][24] Despite the support of a clear scientific consensus, as recently as 2021 one-third of Americans deny that human-caused climate change exists[25] although the majority are concerned or alarmed about the issue.[26]

EnergySince about 26% of all types of energy used in the United States are derived from fossil fuel consumption it is closely linked to greenhouse gas emissions. The energy policy of the United States is determined by federal, state and local public entities, which address issues of energy production, distribution, and consumption, such as building codes and gas mileage advancements. The production and transport of fossil fuels are also tied to significant environmental issues. Species conservationMany plant and animal species became extinct in North America soon after first human arrival, including the North American megafauna; others have become nearly extinct since European settlement, among them the American bison and California condor.[29] The last of the passenger pigeons died in 1914 after being the most common bird in North America. They were killed as both a source of food and because they were a threat to farming. Saving the bald eagle, the national bird of the U.S., from extinction was a notable conservation success. As of 13 December 2016, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature's Red List shows the United States has 1,514 species on its threatened list (critically endangered, endangered and vulnerable categories). Invasive species Invasive species are a crucial threat to many native habitats and species of the United States and a significant cost to agriculture, forestry, and recreation. An invasive species refers to an organism that is not native to a specific region and poses significant economic and environmental threats to its new habitat.[30] The term "invasive species" can also refer to feral species or introduced diseases. Some introduced species, such as the dandelion, do not cause significant economic or ecologic damage and are not widely considered as invasive. Economic damages associated with invasive species' effects and control costs are estimated at $120 billion per year.[31] The main geomorphological impacts of invasive plants include bioconstruction and bioprotection.[32]  DeforestationIn the United States, deforestation was an ongoing process until recently. Between 2010 and 2020, the US forests increased 0.03% annually, according to FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).[a] Native Americans cleared millions of acres of forest for many reasons, including hunting, farming, berry production, and building materials.[33] Prior to the arrival of European-Americans, about one half of the United States land area was forest, about 1,023,000,000 acres (4,140,000 km2) estimated in 1630. Forest cover in the Eastern United States reached its lowest point in roughly 1872 with about 48 percent compared to the amount of forest cover in 1620. The majority of deforestation took place prior to 1910 with the Forest Service reporting the minimum forestation as 721,000,000 acres (2,920,000 km2) around 1920.[34] The forest resources of the United States remained relatively constant through the 20th century.[35] The Forest Service reported total forestation as 766,000,000 acres (3,100,000 km2) in 2012.[36][37][35] A 2017 study estimated 3 percent loss of forest between 1992 and 2001.[38] The 2005 (FAO) Global Forest Resources Assessment ranked the United States as seventh highest country losing its old-growth forests, a vast majority of which were removed prior to the 20th century.[35]MiningMining in the United States has been active since the beginning of colonial times, but became a major industry in the 19th century with a number of new mineral discoveries causing a series of mining rushes. In 2015, the value of coal, metals, and industrial minerals mined in the United States was US$109.6 billion. 158,000 workers were directly employed by the mining industry.[39] The mining industry has a number of impacts on communities, individuals and the environment. Mine safety incidents have been important parts of American occupational safety and health history. Mining has a number of environmental impacts. In the United States, issues like mountaintop removal, and acid mine drainage have widespread impacts on all parts of the environment. As of January 2020, the EPA lists 142 mines in the Superfund program.[40] In 2019, the country was the 4th world producer of gold;[41] 5th largest world producer of copper;[42] 5th worldwide producer of platinum;[43] 10th worldwide producer of silver;[44] 2nd largest world producer of rhenium;[45] 2nd largest world producer of sulfur;[46] 3rd largest world producer of phosphate;[47] 3rd largest world producer of molybdenum;[48] 4th largest world producer of lead;[49] 4th largest world producer of zinc;[50] 5th worldwide producer of vanadium;[51] 9th largest world producer of iron ore;[52] 9th largest world producer of potash;[53] 12th largest world producer of cobalt;[54] 13th largest world producer of titanium;[55] world's largest producer of gypsum;[56] 2nd largest world producer of kyanite;[57] 2nd largest world producer of limestone;[58] in addition to being the 2nd largest world producer of salt.[59] It was the world's 10th largest producer of uranium in 2018.[60]Abandoned fossil fuel wells Though different jurisdictions have varying criteria for what exactly qualifies as an orphaned or abandoned oil well, generally speaking, an oil well is considered abandoned when it has been permanently taken out of production. Similarly, orphaned wells may have different legal definitions across different jurisdictions, but can be thought of as wells whose legal owner it is not possible to determine.[61] Once a well is abandoned, it can be a source of toxic emissions and pollution contaminating groundwater and releasing methane, making orphan wells a significant contributor to national greenhouse gas emissions.[62] For this reason, several state and federal programs have been initiated to plug wells; however, many of these programs are under capacity.[62] In states like Texas and New Mexico, these programs do not have enough funding or staff to fully evaluate and implement mitigation programs.[62] North Dakota dedicated $66 million of its CARES Act pandemic relief funds for plugging and reclaiming abandoned and orphaned wells.[63] According to the Government Accountability Office, the 2.1 million unplugged abandoned wells in the United States could cost as much as $300 billion.[62] A joint Grist and The Texas Observer investigation in 2021 highlighted how government estimates of abandoned wells in Texas and New Mexico were likely underestimated and that market forces might have reduced prices so much creating peak oil conditions that would lead to more abandonment.[62] Advocates of programs like the Green New Deal and broader climate change mitigation policy in the United States have advocated for funding plugging programs that would address stranded assets and provide a Just Transition for skilled oil and gas workers.[64] The REGROW Act, which is part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, includes $4.7 billion in funds for plugging and maintaining orphaned wells.[63] The Interior Department has documented the existence of 130,000 orphaned wells nationwide. An EPA study estimated that there are as many as two to three million wells across the nation. New York State is expecting to receive $70 million from the Act in 2022 which will be used to plug orphaned wells. The state has 6,809 orphaned wells, and the NYSDEC estimates it will cost $248 million to plug them all. The NYSDEC uses a fleet of drones carrying magnetometers to find orphaned wells.[65] In 2023, state governments in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and California reported a shortage of trained staff necessary to implement federally funded well capping programs. Qualified oil field workers were also in short supply in Pennsylvania and Ohio. Federally funded well plugging contracts are required to meet Davis-Bacon Act standards for prevailing wages, in order to ensure that the training of new oil field workers will contribute to local economic development in rural areas.[66]Nuclear The most notable accident involving nuclear power in the United States was Three Mile Island accident in 1979. Davis–Besse Nuclear Power Station has been the source of two of the top five most dangerous nuclear incidents in the United States since 1979.[67] Nuclear safety in the United States is governed by federal regulations and continues to be studied by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). The safety of nuclear plants and materials controlled by the U.S. government for research and weapons production, as well those powering naval vessels, is not governed by the NRC. The anti-nuclear movement in the United States consists of more than eighty anti-nuclear groups which have acted to oppose nuclear power and/or nuclear weapons in the USA. The movement has delayed construction or halted commitments to build some new nuclear plants,[68][69] and has pressured the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to enforce and strengthen the safety regulations for nuclear power plants.[70] Anti-nuclear campaigns that captured national public attention in the 1970s and 1980s involved the Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant, Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant, Diablo Canyon Power Plant, Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant, and Three Mile Island.[68] PesticidesPesticide use in the United States is predominately by the agricultural sector, which in 2012 comprised 89% of conventional pesticide usage in the United States.[71]  The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) was first passed in 1947, giving the United States Department of Agriculture responsibility for regulating pesticides. In 1972, FIFRA underwent a major revision and transferred responsibility of pesticide regulation to the Environmental Protection Agency and shifted emphasis to protection of the environment and public health. Pollution As with many countries, pollution in the United States is a concern for environmental organizations, government agencies, and individuals. Billions of pounds of toxic chemicals are released into the air, land, and waterways in the U.S. each year. In 2019, approximately 21,000 facilities reported releasing 2.16 billion pounds of these chemicals onto land, 580 million pounds into the air, and 201 million pounds into water sources. Exposure to these pollutants can lead to various health problems, from short-term symptoms like headaches and temporary nervous system effects (e.g., "metal fume fever") to serious long-term risks such as cancer and early death.[72] Pollution from U.S. manufacturing has declined massively since 1990 (despite an increase in production). A 2018 study in the American Economic Review found that environmental regulation is the primary driver of the reduction in pollution.[73]Air pollution Air pollution is the introduction of chemicals, particulate matter, or biological materials into the atmosphere that cause harm or discomfort to humans or other living organisms, or damage ecosystems. Health problems attributed to air pollution include premature death, cancer, organ failure, infections, behavioral changes, and other diseases. These health effects are not equally distributed across the U.S. population; there are demographic disparities by race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and education.[74] Air pollution can derive from natural sources, such as wildfires and volcanoes, or from anthropogenic sources. Anthropogenic air pollution has affected the United States since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.[75] According to a 2024 report: "39% of people living in America—131.2 million people—still live in places with failing grades for unhealthy levels of ozone or particle pollution." Analyzing data from 2020 to 2022, the American Lung Association found the number of people living in counties with a failing grade for ozone declined, this year by 2.4 million people.[76] A 2016 study reported that levels of nitrogen oxides, which contribute to smog and acid rain, had plummeted over the previous decade,[77] due to better regulations, economic shifts, and technological innovations. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) reported a 32% decrease of nitrogen dioxide in New York City and a 42% decrease in Atlanta between the periods of 2005–2007 and 2009–2011.[78] During June 2023, due to early season wildfires in Canada, cities like New York and Washington D.C. suffered from dangerous levels of air pollution. It was the worst regional air quality in decades for the Northeast.[79]Water pollution Water pollution in the United States is a growing problem that became critical in the 19th century with the development of mechanized agriculture, mining, and manufacturing industries—although laws and regulations introduced in the late 20th century have improved water quality in many water bodies.[80] Extensive industrialization and rapid urban growth exacerbated water pollution combined with a lack of regulation has allowed for discharges of sewage, toxic chemicals, nutrients, and other pollutants into surface water. This has led to the need for more improvement in water quality as it is still threatened and not fully safe.[81][82] In the early 20th century, communities began to install drinking water treatment systems, but control of the principal pollution sources—domestic sewage, industry, and agriculture—was not effectively regulated in the US until the 1970s.[81] These pollution sources can affect both groundwater and surface water. Multiple pollution incidents such as the Kingston Fossil Plant coal fly ash slurry spill (2008) and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill (2010) have left lasting impacts on water quality, ecosystems, and public health in the United States.[83][84] The United States Geological Survey reported in 2023 that at least 45% of drinking water in the United States contains per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), commonly referred to as "forever chemicals."[85][86] The EPA has been able to identify around 70,000 water bodies that do not meet revised water quality standards due to PFAS.[81] Many solutions to water pollution in the United States can be implemented to curtail water pollution: municipal wastewater treatment, agricultural and industrial wastewater treatment, erosion and sediment control, and the control of urban runoff. The continued implementation of pollution prevention, control, and treatment measures are used to pursue the goal of maintaining water quality within levels specified in federal and state regulations; however, many water bodies across the country continue to violate water quality standards in the 21st century.[87]Marine pollutionPlastic pollutionThe United States is the biggest creator of plastic waste and the third largest source of ocean plastic pollution, e.g. plastic waste that gets into the oceans. Much of the plastic waste generated in the United States is shipped to other countries.[88] Solid wasteAt 760 kg per person the United States generates the greatest amount of municipal waste.[89] In 2018 municipal waste totaled 292.4 million short tons (265.3×106 t), or 4.9 pounds (2.2 kg) per person per day.[90] Policy

Solid waste policy in the United States is aimed at developing and implementing proper mechanisms to effectively manage solid waste. For solid waste policy to be effective, inputs should come from stakeholders, including citizens, businesses, community-based organizations, non-governmental organizations, government agencies, universities, and other research organizations. These inputs form the basis of policy frameworks that influence solid waste management decisions.[91] In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates household, industrial, manufacturing, and commercial solid and hazardous wastes under the 1976 Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA).[92] Effective solid waste management is a cooperative effort involving federal, state, regional, and local entities.[93] Thus, the RCRA's Solid Waste program section D encourages the environmental departments of each state to develop comprehensive plans to manage nonhazardous industrial and municipal solid waste.[92] Each state will have different methods on how to educate and control the flow of waste Electronic waste Electronic waste or e-waste in the United States refers to electronic products that have reached the end of their operable lives, and the United States is beginning to address its waste problems with regulations at a state and federal level. Used electronics are the quickest-growing source of waste and can have serious health impacts.[94] The United States is the world leader in producing the most e-waste, followed closely by China; both countries domestically recycle and export e-waste.[95] Only recently has the United States begun to make an effort to start regulating where e-waste goes and how it is disposed of. There is also an economic factor that has an effect on where and how e-waste is disposed of. Electronics are the primary users of precious and special metals, retrieving those metals from electronics can be viewed as important as raw metals may become more scarce[96] The United States does not have an official federal e-waste regulation system, yet certain states have implemented state regulatory systems. The National Strategy for Electronic Stewardship was co-founded by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), and the General Services Administration (GSA), and was introduced in 2011 to focus on federal action to establish electronic stewardship in the United States.[97] E-waste management is critical due to the toxic chemicals present in electronic devices. According to the United States EPA, toxic substances such as lead, mercury, arsenic, and cadmium are often released into the environment and endanger whole communities; these toxic contaminants can have detrimental effects on the health of ecosystems and living organisms.[98] United States e-waste management includes recycling and reuse programs, domestic landfill dumping, and international shipments of domestically produced e-waste. The EPA estimates that in 2009, the United States disposed of 2.37 million tons of e-waste, 25% of which was recycled domestically.[98] Lack of awareness for e-waste issues is also a problem in the U.S., especially among young people. In a 2020 survey of people between the ages of 18 and 38, 60% did not know what the term "e-waste" is, and 57% did not consider electronic waste to be "a significant contributor to toxic waste."[99] With electronic recycling options readily available in most states, the issue seems to be awareness, not availability. In 2018, an association of European electronic recyclers based in Brussels called the WEEE Forum, created International E-Waste Day on October 13, with the support of 19 e-waste companies globally, in order to raise awareness about how large of an issue e-waste has become.[100]Hazardous waste Under United States environmental policy, hazardous waste is a waste (usually a solid waste) that has the potential to:

Under the 1976 Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), a facility that treats, stores or disposes of hazardous waste must obtain a permit for doing so. Generators of and transporters of hazardous waste must meet specific requirements for handling, managing, and tracking waste. Through RCRA, Congress directed EPA to issue regulations for the management of hazardous waste. EPA developed strict requirements for all aspects of hazardous waste management including the treatment, storage, and disposal of hazardous waste. In addition to these federal requirements, states may develop more stringent requirements or requirements that are broader in scope than the federal regulations. EPA authorizes states to implement the RCRA hazardous waste program. Authorized states must maintain standards that are equivalent to and at least as stringent as the federal program. Implementation of the authorized program usually includes activities such as permitting, corrective action, inspections, monitoring and enforcement.PopulationThe total U.S. population crossed the 100 million mark around 1915, the 200 million mark in 1967, and the 300 million mark in 2006 (estimated on Tuesday, October 17).[101][102] The U.S. population more than tripled during the 20th century – a growth rate of about 1.3 percent a year – from about 76 million in 1900 to 281 million in 2000. This is unlike most European countries, especially Germany, Russia, Italy and Greece, whose populations are slowly declining, and whose fertility rates are below replacement. Population growth is fastest among minorities, and according to the United States Census Bureau's estimation for 2005, 45% of American children under the age of 5 are minorities.[103] In 2007, the nation's minority population reached 102.5 million.[104] A year before, the minority population totaled 100.7 million. Hispanic and Latino Americans accounted for almost half (1.4 million) of the national population growth of 2.9 million between July 1, 2005, and July 1, 2006.[105] Based on a population clock maintained by the U.S. Census Bureau, the current U.S. population, as of July 2021 is about 332 million.[106] A 2004 U.S. Census Bureau report predicted an increase of one third by the year 2050.[107] A subsequent 2008 report projects a population of 439 million, which is a 44% increase from 2008. Conservation and environmental movementToday, the organized environmental movement is represented by a wide range of organizations sometimes called non-governmental organizations or NGOs. These organizations exist on local national and international scales. Environmental NGOs vary widely in political views and in the amount they seek to influence the government. The environmental movement today consists of both large national groups and also many smaller local groups with local concerns. Some resemble the old U.S. conservation movement – whose modern expression is the Nature Conservancy, Audubon Society and National Geographic Society – American organizations with a worldwide influence. See also

NotesReferences

Works cited

Further reading

External links |