|

Favela

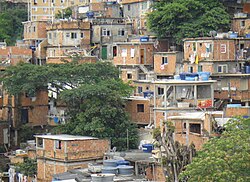

Favela (Portuguese: [fɐˈvɛlɐ]) is an umbrella name for several types of impoverished neighborhoods in Brazil. The term, which means slum or ghetto, was first used in the Slum of Providência in the center of Rio de Janeiro in the late 19th century, which was built by soldiers who had lived under the favela trees in Bahia and had nowhere to live following the Canudos War. Some of the last settlements were called bairros africanos (African neighborhoods). Over the years, many former enslaved Africans moved in. Even before the first favela came into being, poor citizens were pushed away from the city and forced to live in the far suburbs. Most modern favelas appeared in the 1970s due to rural exodus, when many people left rural areas of Brazil and moved to cities. Unable to find places to live, many people found themselves in favelas.[1] Census data released in December 2011 by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) showed that in 2010, about 6 percent of the Brazilian population lived in favelas and other slums. Favelas are located in 323 of the 5,565 Brazilian municipalities.[2] History

The term favela dates back to the late 1800s.[3] At the time, soldiers were brought from the War of Canudos, in the northeastern state of Bahia, to Rio de Janeiro and left with no place to live.[4] When they served in Bahia, those soldiers had been familiar with Canudos' Morro da Favela ("Favela Hill") – a name referring to favela, a skin-irritating tree in the spurge family (Cnidoscolus quercifolius) indigenous to Bahia.[5][6][7] When they settled on the Providência [Providence] hill in Rio de Janeiro, they nicknamed the place Favela hill.[8] The favelas were formed prior to the dense occupation of cities and the domination of real estate interests.[9] Following the end of slavery and increased urbanization into Brazilian cities, a lot of people from the Brazilian countryside moved to Rio. These new migrants sought work in the city but with little to no money, they could not afford urban housing.[10] During the 1950s, the favelas grew to such an extent that they were perceived as a problem for the whole society. At the same time the term favela underwent a first institutionalization by becoming a local category for the settlements of the urban poor on hills. However, it was not until 1937 that the favela actually became central to public attention, when the Building Code (Código de Obras) first recognized their very existence in an official document and thus marked the beginning of explicit favela policies.[11] The housing crisis of the 1940s forced the urban poor to erect hundreds of shantytowns in the suburbs, when favelas replaced tenements as the main type of residence for destitute Cariocas (residents of Rio). The explosive era of favela growth dates from the 1940s, when Getúlio Vargas's industrialization drive pulled hundreds of thousands of migrants into the former Federal District, to the 1970s, when shantytowns expanded beyond urban Rio and into the metropolitan periphery.[12] Urbanization in the 1950s provoked mass migration from the countryside to the cities throughout Brazil by those hoping to take advantage of the economic opportunities urban life provided. Those who moved to Rio de Janeiro chose an inopportune time. The change of Brazil's capital from Rio to Brasília in 1960 marked a slow but steady decline for the former, as industry and employment options began to dry up. Unable to find work, and therefore unable to afford housing within the city limits, these new migrants remained in the favelas. Despite their proximity to urban Rio de Janeiro, the city did not extend sanitation, electricity, or other services to the favelas. They soon became associated with extreme poverty and were considered a headache to many citizens and politicians within Rio. [citation needed] In the 1970s, Brazil's military dictatorship pioneered a favela eradication policy, which forced the displacement of hundreds of thousands of residents. During Carlos Lacerda's administration, many were moved to public housing projects such as Cidade de Deus ("City of God"), later popularized in a widely popular feature film of the same name. Poor public planning and insufficient investment by the government led to the disintegration of these projects into new favelas.[citation needed] By the 1980s, worries about eviction and eradication were beginning to give way to violence associated with the burgeoning drug trade. Changing routes of production and consumption meant that Rio de Janeiro found itself as a transit point for cocaine destined for Europe. Although drugs brought in money, they also accompanied the rise of the small arms trade and of gangs competing for dominance.[citation needed] While there are Rio favelas which are still essentially ruled by organized crime groups like drug traffickers or by organized crime groups called milícias (Brazilian police militias), all of the favelas in Rio's South Zone and key favelas in the North Zone are now managed by Pacifying Police Units, known as UPPs. While drug dealing, sporadic gun fights, and residual control from drug lords remain in certain areas, Rio's political leaders point out that the UPP is a new paradigm after decades without a government presence in these areas.[13] Most of the current favelas greatly expanded in the 1970s, as a construction boom in the more affluent districts of Rio de Janeiro initiated a rural exodus of workers from poorer states in Brazil. Since then, favelas have been created under different terms but with similar results.[citation needed][14] Communities form in favelas over time and often develop an array of social and religious organizations and forming associations to obtain such services as running water and electricity. Sometimes the residents manage to gain title to the land and then are able to improve their homes. Because of crowding, unsanitary conditions, poor nutrition and pollution, disease is rampant in the poorer favelas and infant mortality rates are high. In addition, favelas situated on hillsides are often at risk from flooding and landslides.[15]

Public policy towards favelas

In the late 19th century, the state gave regulatory impetus for the creation of Rio de Janeiro's first squatter settlement. The soldiers from the War of Canudos (1896-7) were granted permission by Ministry of War to settle on the Providência hill, located between the seaside and centre of the city (Pino 1997). The arrival of former black slaves expanded this settlement and the hill became known as Morro de Providência (Pino 1997). The first wave of formal government intervention was in direct response to the overcrowding and outbreak of disease in Providência and the surrounding slums that had begun to appear through internal migration (Oliveira 1996). The simultaneous immigration of White Europeans to the city in this period generated strong demand for housing near the water and the government responded by "razing" the slums and relocating the slum dwellers to Rio's north and south zones (Oliveira 1996, pp. 74). This was the beginning of almost a century of state-sanctioned interventions marked by aggressive eradication policies. Favelas in the early twentieth century were considered breeding grounds for antisocial behavior and spread of disease. The issue of honor pertaining to legal issues was not even considered for residents of the favelas. After a series of comments and events in the neighborhood of Morro da Cyprianna, during which a local woman Elvira Rodrigues Marques was slandered, the Marques family took it to court. This is a significant change in what the public considered the norm for favela residents, who the upper classes considered devoid of honor altogether.[18] Following the initial forced re-relocation, favelas were left largely untouched by the government until the 1940s. During this period politicians, under the auspice of national industrialization and poverty alleviation, pushed for high density public housing as an alternative to the favelas (Skidmore 2010). The "Parque Proletário" program relocated favelados to nearby temporary housing while land was cleared for the construction of permanent housing units (Skidmore 2010). In spite of the political assertions of Rio's Mayor Henrique Dodsworth, the new public housing estates were never built and the once-temporary housing alternatives began to grow into new and larger favelas (Oliveira 1996). Skidmore (2010) argues that "Parque Proletário" was the basis for the intensified eradication policy of the 1960s and 1970s. The mass urban migration to Rio de Janeiro in the 1950s resulted in the proliferation of favelas across the urban terrain. In order to deal with the "favela problem" (Portes 1979, pp. 5), the state implemented a full-scale favela removal program in the 1960s and 1970s that resettled favelados to the periphery of the city (Oliveira 1996). According to Anthony (2013), some of the most brutal favela removals in Rio de Janeiro's history occurred during this period. The military regime of the time provided limited resources to support the transition and favelados struggled to adapt to their new environments that were effectively ostracized communities of poorly built housing, inadequate infrastructure and lacking in public transport connections (Portes 1979). Perlman (2006) points to the state's failure in appropriately managing the favelas as the main reason for the rampant violence, drugs and gang problems that ensued in the communities in the following years. The creation of BOPE (Special Police Operations Battalion) in 1978 was the government's response to this violence (Pino 1997). BOPE, in their all black military ensemble and weaponry, was Rio's attempt to confront violence with an equally opposing entity. In the 1980s and early 1990s, public policy shifted from eradication to preservation and upgrading of the favelas. The "Favela-Bairro" program, launched in 1993, sought to improve living standards for the favelados (Pamuk and Cavallieri 1998). The program provided basic sanitation services and social services, connected favelas to the formal urban community through a series of street connections and public spaces and legalized land tenure (Pamuk and Cavallieri 1998). Aggressive intervention, however, did not entirely disappear from the public agenda. Stray-bullet killings, drug gangs and general violence were escalating in the favelas and from 1995 to mid-1995, the state approved a joint army-police intervention called "Operação Rio" (Human Rights Watch 1996). "Operação Rio" was the state's attempt to regain control of the favelas from the drug factions that were consolidating the social and political vacuum left by previously unsuccessful state policies and interventions (Perlman 2006). Since 2009, Rio de Janeiro has had walls separating the rich neighborhoods from the favelas, officially to protect the natural environment, but critics charge that the barriers are for economic segregation.[19] Pacifying police units Beginning in 2008, Pacifying Police Units (Portuguese: Unidade de Polícia Pacificadora, also translated as Police Pacification Unit), abbreviated UPP, began to be implemented within various favelas in the city of Rio de Janeiro. The UPP is a law enforcement and social services program aimed at reclaiming territories controlled by drug traffickers. The program was spearheaded by State Public Security Secretary José Mariano Beltrame with the backing of Rio Governor Sérgio Cabral. Rio de Janeiro's state governor, Sérgio Cabral, traveled to Colombia in 2007 in order to observe public security improvements enacted in the country under Colombian President Álvaro Uribe since 2000. Following his return, he secured US$1.7 billion for the express purpose of security improvement in Rio, particularly in the favelas. In 2008, the state government unveiled a new police force whose rough translation is Pacifying Police Unit (UPP). Recruits receive special training as well as a US$300 monthly bonus. By October 2012, UPPs have been established in 28 favelas, with the stated goal of Rio's government to install 40 UPPs by 2014. The establishment of a UPP within a favela is initially spearheaded by Rio de Janeiro's elite police battalion, BOPE, in order to arrest or drive out gang leaders. After generally securing an area of heavy weapons and large drug caches, and establishing a presence over several weeks to several months, the BOPE are then replaced by a new Pacifying Police Unit composed of hundreds of newly trained policemen, who work within a given favela as a permanent presence aimed at community policing. Suspicion toward the police force is widespread in the favelas, so working from within is a more effective and efficient means of enacting change. Rio's Security Chief, José Mariano Beltrame, has stated that the main purpose of the UPPs is more toward stopping armed men from ruling the streets than to put an end to drug trafficking. A 2010 report by the World Organization Against Torture (OMCT) did note the drop in the homicide rate within Rio de Janeiro's favelas. The report also pointed to the importance of initiatives that combine public security with intra-favela initiatives. Journalists within Rio studying ballot results from the 2012 municipal elections observed that those living within favelas administered by UPPs distributed their votes among a wider spectrum of candidates compared to areas controlled by drug lords or other organized crime groups such as milícias.[20] More recent rounds of state policy break with the past, as community policing and participatory planning are now cornerstones of Brazilian public policy. Seeking to build on 'Favela-Bairro', the informally coined 'Favela Chic' program was aimed at bringing favelas into the formal social fabric of the city while simultaneously empowering favelados to act as key agents in their communities (Navarro-Sertich 2011). Media outlets have been critical of this change in policy and believe its only reflective of the government's concerns of the large media attention Rio attracted during the 2014 FIFA World Cup (McLoughlin 2011) and the 2016 Olympic Games (Griffin 2016). Anthony (2013) was equally as critical of the policy and said that while rhetoric asserted the government's best intention, the reality was more in line with aggressive policies of the past. He points to the announcement in 2010 from Rio's Mayor Eduardo Paes concerning the removal of two inner city favelas, Morro de Prazeres and Laboriaux, and the forced relocation of its residents. There have been significant shifts in favela policy in the last century. In 2020, a Civil Police report shows that the city of Rio de Janeiro has 1,413 favelas, all under the control of a parallel armed power (drug trafficking or armed militia).[21] Due to the large scale and complexities of these informal settlements, academic interest into this field remains high.    Formation of favela society and culture  The people who live in favelas are known as favelados ("inhabitants of favela"). Favelas are associated with poverty. Brazil's favelas are the result of the unequal distribution of wealth in the country. Brazil is one of the most economically unequal countries in the world, with the top 10 percent of its population earning 50 percent of the national income and about 8.5 percent of all people living below the poverty line.[22] As a result, residents of favelas are often discriminated against for living in these communities and often experience inequality and exploitation.[23] This stigma that is associated with people living in favelas can lead to difficulty in finding jobs.[23] The Brazilian government has made several attempts in the 20th century to improve the nation's problem of urban poverty. One way was by the eradication of the favelas and favela dwellers that occurred during the 1970s while Brazil was under military governance. These favela eradication programs forcibly removed over 100,000 residents and placed them in public housing projects or back to the rural areas that many emigrated from.[24] Another attempt to deal with urban poverty came by way of gentrification. The government sought to upgrade the favelas and integrate them into the inner city with the newly urbanized upper-middle class. As these "upgraded favelas" became more stable, they began to attract members of the lower-middle class pushing the former favela dwellers onto the streets or outside of the urban center and into the suburbs further away from opportunity and economic advancement. For example: in Rio de Janeiro, the vast majority of the homeless population is black, and part of that can be attributed to favela gentrification and displacement of those in extreme poverty.[25] Drugs in the favelasThe cocaine trade has affected Brazil and in turn its favelas, which tend to be ruled by drug lords. Regular shoot-outs between traffickers and police and other criminals, as well as assorted illegal activities, lead to murder rates in excess of 40 per 100,000 inhabitants in the city of Rio and much higher rates in some Rio favelas.[26] Traffickers ensure that individual residents can guarantee their own safety through their actions and political connections to them. They do this by maintaining order in the favela and giving and receiving reciprocity and respect, thus creating an environment in which critical segments of the local population feel safe despite continuing high levels of violence. Drug use is highly concentrated in these areas run by local gangs in each highly populated favela. Drug sales run rampant at night when many favelas host their own baile, or dance party, where many different social classes can be found. These drug sales make up a business that in some of the occupied areas rakes in as much as US$150 million per month, according to official estimates released by the Rio media.[27] Growth and removal of the favelasDespite attempts to remove favelas from Brazil's major cities like Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, the poor population grew at a rapid pace as well as the modern favelas that house them in the end of last century. This is a phenomenon called "favelização" ("favela growth" or "favelisation"). In 1969, there were approximately 300 favelas in Rio de Janeiro; today there are twice as many. In 1950, only 7 percent of Rio de Janeiro's population lived in favelas; in the present day this number has grown to 19 percent or about one in five people living in a favela. According to national census data, from 1980 to 1990, the overall growth rate of Rio de Janeiro dropped by 8 percent, but the favela population increased by 41 percent. After 1990, the city's growth rate leveled off at 7 percent, but the favela population increased by 24 percent. A report released in 2010 by the United Nations, however, shows that Brazil has reduced its slum population by 16%, now corresponding to about 6% of the overall population of the nation.[28]  ReligionA number of religious traditions exist in the favelas. Historically, Umbanda and Candomblé are the most prominent religions within favelas, but over the past few decades there has been a shift toward Evangelicalism, including Pentecostalism.[15] While there has been an increase in the number of converts to Evangelicalism, there are also an increasing number of people who claim to be non-religious.[23] MusicPopular types of music in favelas include funk, hip-hop, and Samba.[29] Recently, funk carioca, a type of music popularized in the favelas has also become popular in other parts of the world.[30] This type of music often features samples from other songs. Popular funk artists include MC Naldo and Buchecha[30] Bailes funk are forms of dance parties that play this type of funk music and were popularized in favelas.[23] Popular hip hop artist MV Bill is from Cidade de Deus in Rio de Janeiro.[23] Favela Brass is a free music school set up in Pereirão in Rio, which aims to give children opportunities through musical performance.[31] Popularization of favela cultureMedia representations of favelas also serve to spread knowledge of favelas, contributing to the growing interest in favelas as tourist locations.[29] In recent years, favela culture has gained popularity as inspiration for art in other parts of the world. Fascination with favela life can be seen in many paintings, photography, and reproductions of favela dwellings.[23] There have also been instances of European nightclubs inspired by favelas.[23] TourismSince the mid-1990s, a new form of tourism has emerged in globalizing cities of several so-called developing countries or emerging nations. Visits to the most disadvantaged parts of the city are essential features of this form of tourism. It is mainly composed of guided tours, marketed and operated by professional companies, through these disadvantaged areas. This new form of tourism has often been referred to as slum tourism which can also be seen in areas of South Africa and India.[32]  In Brazil, this new growing market of tourism has evolved in a few particular favelas mostly in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, with the largest and most visited favela being Rocinha. This new touristic phenomena has developed into a major segment of touristic exploration.[11] There are conflicting views on whether or not favela tourism is an ethical practice.[29] These tours draw awareness to the needs of the underprivileged population living in these favelas, while giving tourists access to a side of Rio that often lurks in the shadows. The tours are viewed as a spectacular alternative to mainstream Rio de Janeiro attractions, such as Sugarloaf Mountain and Christ the Redeemer. They offer a brief portrayal of Rio's hillside communities that are far more than the habitats often misrepresented by drug lords and criminals.[33] For instance, there are tours of the large favela of Rocinha. Directed by trained guides, tourists are driven up the favela in vans, and then explore the community's hillside by foot. Guides walk their groups down main streets and point out local hot spots. Most tours stop by a community center or school, which are often funded in part by the tour's profits. Tourists are given the opportunity to interact with local members of the community, leaders, and area officials, adding to their impressions of favela life. Depending on the tour, some companies will allow pictures to be taken in predetermined areas, while others prohibit picture-taking completely.[33] Notable features of said tours include:[32]

The Brazilian federal government views favela tourism with high regard. The administration of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva initiated a program to further implement tourism into the structure of favela economies. The Rio Top Tour Project, inaugurated in August 2010, promotes tourism throughout the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Beginning in Santa Marta, a favela of approximately 5,000 Cariocas, federal aid was administered in order to invigorate the tourism industry. The federal government has dedicated 230 thousand Reais (US$145 thousand) to the project efforts in Santa Marta. English signs indicating the location of attractions are posted throughout the community, samba schools are open, and viewing stations have been constructed so tourists can take advantage of Rio de Janeiro's vista. Federal and state officials are carrying out marketing strategies and constructing information booths for visitors. Residents have also been trained to serve as tour guides, following the lead of pre-existing favela tour programs.[33] Recently, favelas have been featured in multiple forms of media including movies and video games. The media representation of favelas has increased peoples' interest in favelas as tourist locations.[29]  In popular culture

See also

References

Further reading

External links

|