|

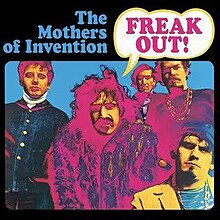

Freak Out!

Freak Out! is the debut studio album by the American rock band the Mothers of Invention, released on June 27, 1966, by Verve Records. Often cited as one of rock music's first concept albums, it is a satirical expression of guitarist/bandleader Frank Zappa's perception of American pop culture and the nascent freak scene of Los Angeles. It was the second rock music double album ever released, following Bob Dylan's Blonde on Blonde just one week earlier,[2] as well as the first double debut album by a rock artist. In the UK, the album was originally released as an edited single disc. The album was produced by Tom Wilson, who signed the Mothers, formerly a bar band called the Soul Giants. Zappa said many years later that Wilson signed the band to a record deal under the impression that they were a white blues band. The album features Zappa on vocals and guitar, along with lead vocalist/tambourine player Ray Collins, bass player/vocalist Roy Estrada, drummer/vocalist Jimmy Carl Black and guitar player Elliot Ingber (later of Captain Beefheart's Magic Band, performing there under the pseudonym "Winged Eel Fingerling").[3][4] The band's original repertoire consisted of rhythm and blues covers, but after Zappa joined the band, he encouraged them to play his own original material, and their name was changed to the Mothers. The musical content of Freak Out! ranges from rhythm and blues, doo-wop,[5] and standard blues-influenced rock to orchestral arrangements and avant-garde sound collages. Although the album was initially poorly received in the United States, it was a success in Europe. It gained a cult following in America, where it continued to sell in substantial quantities until it was discontinued in the early 1970s. The album went back in print in 1985, as part of Zappa's Old Masters Box One box set, with the first CD release of the album following in 1987. In 1999, the album was honored with the Grammy Hall of Fame Award, and in 2003, Rolling Stone ranked it among the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". In 2006, The MOFO Project/Object, an audio documentary on the making of the album, was released in honor of its 40th anniversary. BackgroundIn the early 1960s, Zappa met Ray Collins. Collins supported himself by working as a carpenter, and on weekends sang with a group called the Soul Giants. In April 1965, Collins got into a fight with their guitar player, who quit, leaving the band in need of a substitute, and Zappa filled in.[6][7] The Soul Giants' repertoire originally consisted of R&B covers. After Zappa joined the band he encouraged them to play his own original material and try to get a record contract.[8] While most of the band members liked the idea, then-leader and saxophone player Davy Coronado felt that performing original material would cost them bookings, and quit the band.[6][9] Zappa took over leadership of the band, who officially changed their name to the Mothers on May 10, 1965.[6] The group moved to Los Angeles in the summer of 1965 after Zappa got them a management contract with Herb Cohen. They gained steady work at clubs along the Sunset Strip. MGM staff producer Tom Wilson offered the band a record deal with the Verve Records division in early 1966. He had heard of their growing reputation but had seen them perform only one song, "Trouble Every Day", which concerned the Watts riots.[7] According to Zappa, this led Wilson to believe that they were a "white blues band".[6][9] RecordingThe first two songs recorded for the album were "Any Way the Wind Blows" and "Who Are the Brain Police?"[6][7] When Tom Wilson heard the latter, he realized that the Mothers were not merely a blues band. Zappa remembered "I could see through the window that he was scrambling toward the phone to call his boss—probably saying: 'Well, uh, not exactly a 'white blues band', but ... sort of.'"[6] In a 1968 article written for Hit Parader magazine, Zappa wrote that when Wilson heard these songs, "he was so impressed he got on the phone and called New York, and as a result I got a more or less unlimited budget to do this monstrosity."[7] Freak Out! is an early example of the concept album, a sardonic farce about rock music and America. "All the songs on it were about something", Zappa wrote in The Real Frank Zappa Book. "It wasn't as if we had a hit single and we needed to build some filler around it. Each tune had a function within an overall satirical concept."[6]

The album was recorded at TTG Studios in Hollywood, California, between March 9 and March 12, 1966.[11] Some songs, such as "Motherly Love" and "I Ain't Got No Heart", had already been recorded in earlier versions prior to the Freak Out! sessions. These recordings, said to have been made around 1965,[11] were not officially released until 2004, when they appeared on the posthumous Zappa album Joe's Corsage. An early version of the song "Any Way the Wind Blows", recorded in 1963,[12] appears on another posthumous release, The Lost Episodes, and was originally written when Zappa considered divorcing first wife Kay Sherman.[12][13] In the liner notes for Freak Out!, Zappa wrote, "If I had never gotten divorced, this piece of trivial nonsense would never have been recorded."[13] "Hungry Freaks, Daddy" is an attack on the American school system[13] that musically quotes a Rolling Stones song, "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction", in its opening measures, and contains a guitar solo between the first and second verses that itself briefly quotes Richard Berry's 1959 song "Have Love, Will Travel".[14] Tom Wilson became more enthusiastic as the sessions continued. In the middle of the week of recording, Zappa told him, "I would like to rent $500 [equivalent to $4,700 in 2023] worth of percussion equipment for a session that starts at midnight on Friday and I want to bring all the freaks from Sunset Boulevard into the studio to do something special." Wilson agreed. The material was worked into "Cream Cheese", a "ballet in two tableaux"[13] that was eventually retitled "The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet".[6] In a November 1967 radio interview (posthumously included as part of the 2006 MOFO album), Zappa is heard complaining that the version of "Monster Magnet" released on Freak Out! was in fact an unfinished piece; the percussion track was intended to serve as the foundation for an even more complex piece, but MGM refused to approve the studio time needed to record the intended overdubs that would have completed the composition, and so it was released (to Zappa's great dissatisfaction) in this unfinished form.[13][15] In addition to the Mothers, some tracks featured a "Mothers' Auxiliary"[13] that consisted of additional session players, including noted "Wrecking Crew" members Gene Estes, Carol Kaye and Mac Rebennack (aka Dr. John), guitarist Neil Levang, and jazz-soul pianists Eugene DiNovi and Les McCann, with vocal contributions by Paul Butterfield, Kim Fowley, Jeannie Vassoir and future Mother Jim Sherwood. Several orchestral musicians, who were also mostly credited as members of the Auxiliary (including their contractor, Benjamin Barrett), also made contributions to several songs at certain sessions, chiefly in the form of backing tracks on those songs.[13] Zappa later found out that when the material was recorded, Wilson had taken LSD. "I've tried to imagine what [Wilson] must have been thinking", Zappa recounted, "sitting in that control room, listening to all that weird shit coming out of the speakers, and being responsible for telling the engineer, Ami Hadani (who was not on acid), what to do."[6] By the time Freak Out! was edited and shaped into an album, Wilson had spent $25–35,000 of MGM's money (equivalent to $330,000 in 2023).[6][16] In Hit Parader magazine, Zappa wrote that "Wilson was sticking his neck out. He laid his job on the line by producing the album. MGM felt that they had spent too much money on the album."[7] An early version of the album was done in April, with a different track order from the final sequence completed two months later:[17][18][11] for instance, "Wowie Zowie" (which would eventually begin side two of the finalized sequence instead, and was described by Zappa as "harmless", "cheerful" and apparently liked by Little Richard)[13] was the original planned lead-off track rather than "Hungry Freaks, Daddy", "Trouble Comin' Every Day" (which was inspired by the Watts Riots that took place the previous year)[13] was included on side one rather than side three, and "Who Are the Brain Police?" (acknowledged by Zappa himself as one of the scariest songs on the album)[13] took up the middle of side two rather than the middle of side one, with only "Help, I'm a Rock" (a song dedicated to Elvis Presley)[13] and "Cream Cheese" (later retitled "The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet") taking up the same concluding places on the early sequence that they eventually would on the finalized sequence.[17][18] "Wowie Zowie" itself originally contained a musique concrète section between the bridge and third verse that would eventually be edited out of the song as it appeared on the finalized sequence,[18] while the third section of "Help, I'm a Rock", called "It Can't Happen Here", contained two additional lines consisting of the word "psychedelic" during the self-pleasure sequence and of the words "...since you first took the shots" immediately following the "we've been very interested in your development" line.[18][19] Tapes of the early sequence were eventually leaked to European collectors and bootlegged on vinyl as The Alternate Freak Out! in 2010,[17][18] with long-time Zappa associate Scott Parker later describing the early sequence's track order as having more conceptual "integrat[ion]" and "a greater amount of weirdness sprinkled throughout" than that of the finalized sequence during a 2011 podcast.[18] The label eventually requested that the two lines in question be removed from the "It Can't Happen Here" section of "Help, I'm a Rock",[20] both of which had been interpreted by MGM executives to be drug references. However, the label either had no objections to, or else did not notice, a sped-up recording of Zappa shouting the word "fuck" after accidentally smashing his finger,[19] occurring at 11 minutes and 36 seconds into "The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet". From the 1995 CD reissue of the album onwards, the formerly three-part "Help, I'm a Rock" was reindexed as two separate tracks, with only the first two parts ("Okay To Tap Dance" and "In Memoriam, Edgard Varèse"[21]) remaining under the "Help, I'm a Rock" title but with "It Can't Happen Here" becoming its own track, as "It Can't Happen Here" had been included by itself on the 1969 vinyl compilation Mothermania, where the two normally censored lines were also reinstated.[22][23] MGM also told Zappa that the band would have to change their name, claiming that no DJ would play a record on the air by a group called "the Mothers".[6][24]

ReleaseVerve released Freak Out! on June 27, 1966.[25] The band's name was changed to the Mothers of Invention, a name Zappa chose in favor of MGM's original suggested name, "The Mothers Auxiliary".[26] The album's back cover included a "letter" from Zappa-created fictional character Suzy Creamcheese (who also appears on the album itself), which read:

Because the text was printed in a typeface resembling typewriter lettering, some people thought that Suzy Creamcheese was real, and many listeners expected to see her in concert performances. Because of this, it was decided that "it would be best to bring along a Suzy Creamcheese replica who would demonstrate once and for all the veracity of such a beast."[28] Because the original voice of Suzy Creamcheese, Jeannie Vassoir, was unavailable, Pamela Zarubica took over the part.[28] Early pressings of the album in the United States included a blurb for a "Freak Out Hot Spots!" map. Inside the gatefold jacket the small ad was aimed at people coming to visit Los Angeles and it listed several famous restaurants and clubs including Canter's and The Whisky a Go Go. The ad also claimed information concerning police arrests. It states: "Also shows where the heat has been busting frequently, with tips on safety in police terror situations". Those interested in the map were instructed to send $1.00 (US$9 in 2023 dollars[16]) to MGM Records c/o 1540 Broadway NY. NY. address. The map was only available for a limited time, since the blurb was not included on later pressings and the space was left blank.[23] It was eventually reprinted and included with The MOFO Project/Object, a four-disc audio documentary on the making of the album, released posthumously by the Zappa Family Trust in 2006.[29][30] Reception

Freak Out! reached No. 130 on the Billboard chart,[39] and was not a critical success when it was first released in the United States.[9] Many listeners were convinced that the album was drug-inspired,[6] and interpreted the album's title as slang for a bad LSD trip. The album made the Mothers of Invention immediate underground darlings with a strong counter-cultural following.[40] In The Real Frank Zappa Book, Zappa quotes a negative review of the album by Pete Johnson of the Los Angeles Times, who wrote:

The album developed a major cult following in the United States by the time MGM/Verve had been merged into a division of PolyGram in 1972. At that time many MGM/Verve releases including Freak Out! were prematurely deleted in an attempt to keep the struggling company financially solvent. Zappa had already moved on to his own companies Bizarre Records and Straight Records, which were distributed by Warner Bros. Records. Freak Out! was initially more successful in Europe and quickly influenced many English rock musicians.[19] According to David Fricke, the album was a major influence on the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[42] Paul McCartney regarded Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band as the Beatles' Freak Out! [43] Zappa criticized the Beatles, as he felt they were "only in it for the money".[44] Freak Out! was honored with the Grammy Hall of Fame Award in 1999,[45] ranked at number 243 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time in 2003,[46] and 246 in a 2012 revised list.[47] It was also featured in the 2006 book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[48] The album was named as one of Classic Rock magazine's "50 Albums That Built Prog Rock".[49] It was voted number 315 in the third edition of Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000).[50] Track listingAll tracks are written by Frank Zappa except "Go Cry on Somebody Else's Shoulder", by Zappa and Ray Collins

On the 1995 and 2012 CD releases, "Help, I'm a Rock" is credited as two tracks: "Help, I'm a Rock" (4:43) and "It Can't Happen Here" (3:57). On the Side 3 label of original vinyl copies, "Trouble Every Day" is listed as "Trouble Comin' Every Day". PersonnelThe Mothers of Invention

The Mothers' Auxiliary

Production credits

Charts

References

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||