|

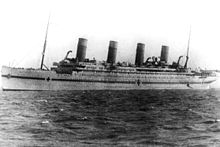

HMHS Britannic

HMHS Britannic (originally to be the RMS Britannic) (/brɪˈtænɪk/) was the third and final vessel of the White Star Line's Olympic class of steamships and the second White Star ship to bear the name Britannic. She was the youngest sister of the RMS Olympic and the RMS Titanic and was intended to enter service as a transatlantic passenger liner. She was operated as a hospital ship from 1915 until her sinking near the Greek island of Kea, in the Aegean Sea, in November 1916. At the time she was the largest hospital ship in the world. Britannic was launched just before the start of the First World War. She was designed to be the safest of the three ships with design changes made during construction due to lessons learned from the sinking of the Titanic. She was laid up at her builders, Harland and Wolff, in Belfast for many months before being requisitioned as a hospital ship. In 1915 and 1916 she served between the United Kingdom and the Dardanelles. On the morning of 21 November 1916 she hit a naval mine of the Imperial German Navy near the Greek island of Kea and sank 55 minutes later, killing 30 of 1,066 people on board; the 1,036 survivors were rescued from the water and lifeboats. Britannic was the largest ship lost in the First World War.[3] After the War, the White Star Line was compensated for the loss of Britannic by the award of SS Bismarck as part of postwar reparations; she entered service as RMS Majestic. The wreck of the Britannic was located and explored by Jacques Cousteau in 1975. The vessel is the largest intact passenger ship on the seabed in the world.[4] It was bought in 1996 and is currently owned by Simon Mills, a maritime historian. CharacteristicsThe original dimensions of Britannic were similar to those of her older sisters, but her dimensions were altered whilst still on the building stocks after the loss of Titanic. With a gross tonnage of 48,158, she surpassed her older sisters in terms of internal volume, but this did not make her the largest passenger ship in service at that time; the German SS Vaterland held this title with a significantly higher tonnage.[5] The Olympic-class ships were propelled by a combined system of two triple-expansion steam engines which powered the three-bladed outboard wing propellers whilst a low-pressure steam turbine used steam exhausted from the two reciprocating engines to power the central four-bladed propeller giving a maximum speed of 23 knots.[6] Post-Titanic design changes Britannic had a similar layout to her sister ships. Following the Titanic disaster and the subsequent inquiries, several design changes were made to the remaining Olympic-class liners. With Britannic, these changes made before launch included increasing the ship's beam to 94 feet (29 m) to allow for a double hull along the engine and boiler rooms and raising six out of the 15 watertight bulkheads up to B Deck. Additionally, a larger 18,000 horsepower (13,000 kW) turbine was added instead of the 16,000 horsepower (12,000 kW) units installed on the earlier vessels to make up for the increase in hull width. The central watertight compartments were enhanced, allowing the ship to stay afloat with six compartments flooded.[7] Externally the largest visual change was the fitting of large crane-like gantry davits, each powered by an electric motor and capable of launching six lifeboats which were stored on gantries; the ship was designed to have eight sets of gantry davits but only five were installed before Britannic entered war service, with the difference being made up with boats launched by manually operated Welin-type davits as on Titanic and Olympic.[8][9] Additional lifeboats could be stored within reach of the davits on the deckhouse roof, and the gantry davits could reach lifeboats on the other side of the ship, providing that none of the funnels was obstructing the way. This design enabled all the lifeboats to be launched, even if the ship developed a list that would normally prevent lifeboats from being launched on the side opposite to the list. Several of these davits were placed abreast of funnels, defeating that purpose. The elevators, which previously stopped at A deck, could now reach the boat deck.[10] The ship carried 48 lifeboats, capable of carrying at least 75 people each. Thus, at least 3,600 people could be carried by the lifeboats, which was well above the ship's maximum capacity of 3,309. HistoryConceptionIn 1907, J. Bruce Ismay, director general of the White Star Line, and Lord Pirrie, chairman of the Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast had decided to build a trio of ocean liners of unmatched size to compete with the Cunard Line's Lusitania and Mauretania not in terms of speed but in terms of luxury and safety.[11] The names of the three vessels were decided at a later date and they showed the intention of the designers regarding their size: Olympic, Titanic and Britannic.[12] Construction of the Olympic and the Titanic began in 1908 and 1909 respectively.[13] Their sizes were so large that it was necessary to build the Arrol Gantry to shelter them, wide enough to span the two new building slips and allow two ships to be built at a time.[14] The three ships were designed to be 270 metres long and to have a gross tonnage of over 45,000. Their designed speed was approximately 22 knots, well below that of the Lusitania and Mauretania, but still allowing for a transatlantic crossing of less than one week.[15] Rumoured name-change Although the White Star Line and the Harland and Wolff shipyard always denied it,[10][16] some sources claim that Britannic was to be named Gigantic, but her name was changed so as not to compete with Titanic or create comparisons.[17][1] One source is a poster of the ship with the name Gigantic at the top.[18] Other sources are November 1911 American newspapers stating the White Star order for Gigantic being placed, as well as other newspapers from around the world both during construction and immediately after the sinking of the Titanic.[19][20][21][22] Tom McCluskie stated that in his capacity as archive manager and historian at Harland and Wolff, he "never saw any official reference to the name Gigantic being used or proposed for the third of the Olympic-class vessels".[23][24] Some hand-written changes were added to the order book and dated January 1912. These only dealt with the ship's moulded width, not her name.[24] Construction  Britannic's keel was laid on 30 November 1911 at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, on the gantry slip previously occupied by Olympic, 13 months after the launch of that ship, and Arlanza, launched seven days before.[9] The acquisition of the ship was planned to be at the beginning of 1914.[25] Due to improvements introduced as a consequence of the Titanic's disaster, Britannic was not launched until 26 February 1914,[26] which was filmed along with the fitting of a funnel.[27] Several speeches were given in front of the press, and a dinner was organised in honour of the launching.[28] Fitting out began subsequently. The ship entered dry dock in September and her propellers were installed.[29] Reusing Olympic's space saved the shipyard time and money by not clearing out a third slip similar in size to those used for the two previous vessels. In August 1914, before Britannic could commence transatlantic service between New York and Southampton, the First World War began. Immediately, all shipyards with Admiralty contracts were given priority to use available raw materials. All civil contracts including Britannic were slowed.[30] The naval authorities requisitioned a large number of ships as armed merchant cruisers or for troop transport. The Admiralty paid the companies for the use of their ships but the risk of losing a ship in naval operations was high. The larger ocean liners were not initially taken for naval use, because smaller ships were easier to operate. Olympic returned to Belfast on 3 November 1914, while work on Britannic continued slowly.[30] Requisition The need for increased tonnage grew critical as naval operations extended to the Eastern Mediterranean. In May 1915, Britannic completed mooring trials of her engines, and was prepared for emergency entrance into service with as little as four weeks' notice. The same month also saw the first major loss of a civilian ocean liner when Cunard's RMS Lusitania was torpedoed near the Irish coast by SM U-20.[31] The following month, the Admiralty decided to use recently requisitioned passenger liners as troop transports in the Gallipoli Campaign (also called the Dardanelles service). The first to sail were Cunard's RMS Mauretania and RMS Aquitania. As the Gallipoli landings proved to be disastrous and the casualties mounted, the need for large hospital ships for treatment and evacuation of wounded became evident. Aquitania was diverted to hospital ship duties in August (her place as a troop transport would be taken by Olympic in September). Then on 13 November 1915, Britannic was requisitioned as a hospital ship from her storage location at Belfast.[citation needed] Repainted white with large red crosses and a horizontal green stripe, she was renamed HMHS (His Majesty's Hospital Ship) Britannic[30] and placed under the command of Captain Charles Alfred Bartlett.[32] In the interior, 3,309 beds and several operating rooms were installed. The common areas of the upper decks were transformed into rooms for the wounded. The cabins of B Deck were used to house doctors. The first-class dining room and the first-class reception room on D Deck were transformed into operating rooms. The lower bridge was used to accommodate the lightly wounded.[32] The medical equipment was installed on 12 December 1915.[30] First service When declared fit for service on 12 December 1915 at Liverpool, Britannic was assigned a medical team consisting of 101 nurses, 336 non-commissioned officers and 52 commissioned officers as well as a crew of 675 people.[32] On 23 December, she left Liverpool to join the port of Mudros on the island of Lemnos on the Aegean Sea to bring back sick and wounded soldiers.[33] She joined with several ships on the same route, including Mauretania, Aquitania,[34] and her sister ship Olympic.[35] The four ships were joined a little later by Statendam.[36] She made a stopover at Naples before continuing to Mudros, in order for her stock of coal to be replenished. After she returned, she spent four weeks as a floating hospital off the Isle of Wight.[37] The third voyage was from 20 March 1916 to 4 April. The Dardanelles was evacuated in January.[38] At the end of her military service on 6 June 1916, Britannic returned to Belfast to undergo the necessary modifications for transforming her into a transatlantic passenger liner. The British government paid the White Star Line £75,000 to compensate for the conversion. The transformation took place for several months before being interrupted by a recall of the ship back into military service.[39] RecalledThe Admiralty recalled Britannic back into service as a hospital ship on 26 August 1916, and the ship returned to the Mediterranean Sea for a fourth voyage on 24 September of that year.[40] On 29 September on her way to Naples, she encountered a violent storm from which she emerged unscathed.[41] She left on 9 October for Southampton. Then, she made a fifth trip, which was marked by a quarantining of the crew when the ship arrived at Mudros (now Moudros) because of food-borne illness.[42] Life aboard the ship followed a routine. At six o'clock, the patients were awakened and the premises were cleaned up. Breakfast was served at 6:30 AM, then the captain toured the ship for an inspection. Lunch was served at 12:30 PM and tea at 4:30 PM. Patients were treated between meals and those who wished to go for a walk could do so. At 8:30 PM, the patients went to bed and the captain made another inspection tour.[33] There were medical classes available for training the nurses.[43] Last voyageThe channel between Makronisos (near top) and Kea (bottom); Britannic sank closer to Kea After completing five successful voyages to the Middle Eastern theatre and back to the United Kingdom transporting the sick and wounded, Britannic departed Southampton for Lemnos at 14:23 on 12 November 1916, her sixth voyage to the Mediterranean Sea.[32] The ship passed Gibraltar around midnight on 15 November and arrived at Naples on the morning of 17 November, for her usual coaling and water-refuelling stop, completing the first stage of her mission.[44] A storm kept the ship at Naples until Sunday afternoon when Captain Bartlett decided to take advantage of a brief break in the weather and continue. The seas rose once again as Britannic left the port. By the next morning, the storms died and the ship passed the Strait of Messina without problems. Cape Matapan was rounded in the first hours of 21 November. By morning, Britannic was steaming at full speed into the Kea Channel, between Cape Sounion (the southernmost point of Attica, the prefecture that includes Athens) and the island of Kea.[44] There were 1,066 people on board: 673 crew, 315 Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), 77 nurses, and the captain.[45] Explosion At 08:12 am European Eastern Time Britannic was rocked by an explosion after hitting a mine.[47] The mines had been planted in the Kea Channel on 21 October 1916 by SM U-73 under the command of Gustav Sieß. The reaction in the dining room was immediate; doctors and nurses left instantly for their posts but not everybody reacted the same way, as further aft, the power of the explosion was less felt, and many thought the ship had hit a smaller boat. Captain Bartlett and Chief Officer Hume were on the bridge at the time and the gravity of the situation was soon evident.[48] The explosion was on the starboard[48] side, between holds two and three. The force of the explosion damaged the watertight bulkhead between hold one and the forepeak.[47] The first four watertight compartments were filling rapidly with water,[47] the boiler-man's tunnel connecting the firemen's quarters in the bow with boiler room six was seriously damaged, and water was flowing into that boiler room.[47] Bartlett ordered the watertight doors closed, sent a distress signal, and ordered the crew to prepare the lifeboats.[47] An SOS signal was immediately sent out and was received by several other ships in the area, among them HMS Scourge and HMS Heroic, but Britannic heard nothing in reply. Unknown to either Bartlett or the ship's wireless operator, the force of the first explosion had caused the antenna wires slung between the ship's masts to snap. This meant that although the ship could still send out transmissions by radio, she could no longer receive them.[49] Along with the damaged watertight door of the firemen's tunnel, the watertight door between boiler rooms six and five failed to close properly.[47] Water was flowing further aft into boiler room five. Britannic had reached her flooding limit. She could stay afloat (motionless) with her first six watertight compartments flooded. There were five watertight bulkheads rising all the way up to B Deck.[50] Those measures had been taken after the Titanic disaster (Titanic could float with only her first four compartments flooded).[51] The next crucial bulkhead between boiler rooms five and four and its door were undamaged and should have guaranteed the ship's survival. However, there were open portholes along the front lower decks, which tilted underwater within minutes of the explosion. The nurses had opened most of those portholes to ventilate the wards, against standing orders. As the ship's angle of list increased, water reached this level and began entering aft from the bulkhead between boiler rooms five and four. With more than six compartments flooded, Britannic could not stay afloat.[51] EvacuationOn the bridge, Captain Bartlett was already considering efforts to save the ship. Only two minutes after the blast, boiler rooms five and six had to be evacuated. In about ten minutes, Britannic was roughly in the same condition Titanic had been in one hour after the collision with the iceberg. Fifteen minutes after the ship was struck, the open portholes on E Deck were underwater. With water also entering her aft section from the bulkhead between boiler rooms four and five, Britannic quickly developed a serious list to starboard.[52] Bartlett gave the order to turn starboard towards the island of Kea in an attempt to beach her. The effect of Britannic's starboard list and the weight of the rudder made attempts to navigate the ship under her own power difficult, and the steering gear had been knocked out by the explosion, which eliminated steering by the rudder. The captain ordered the port shaft driven at a higher speed than the starboard side, which helped the ship move towards Kea.[52] At the same time, the hospital staff prepared to evacuate. Bartlett had given the order to prepare the lifeboats, but he did not allow them to be lowered into the water. Everyone took their most valuable belongings with them before they evacuated. The chaplain of the ship recovered his Bible. The few patients and nurses on board were assembled. Major Harold Priestley gathered his detachments from the Royal Army Medical Corps to the back of the A deck and inspected the cabins to ensure no one was left behind.[52] While Bartlett continued his desperate manoeuvre, Britannic's list steadily increased. Fearing that the list would become too large to launch, some crew decided to launch lifeboats without waiting for the order to do so.[52] Two lifeboats were put onto the water on the port side without permission by Third Officer Francis Laws. These boats were drawn towards the still-turning, partly surfaced propellers. Bartlett ordered the engines to stop but before this could take effect, the two boats were drawn into the propellers, completely destroying both and killing 30 people.[51] Bartlett was able to stop the engines before any more boats were lost.[53] Final momentsBy 08:50, most of those on board had escaped in the 35 successfully launched lifeboats. At this point, Bartlett concluded that the rate at which Britannic was sinking had slowed so he called a halt to the evacuation and ordered the engines restarted in the hope that he might still be able to beach the ship.[54] At 09:00 Bartlett was informed that the rate of flooding had increased due to the ship's forward motion and that the flooding had reached D-deck. Realising that there was now no hope of reaching land in time, Bartlett gave the final order to stop the engines and sounded two final long blasts of the whistle, the signal to abandon ship.[55] As water reached the bridge, he and Assistant Commander Dyke walked off onto the deck and entered the water, swimming to a collapsible boat from which they continued to coordinate the rescue operations.[56] Britannic gradually capsized to starboard, and the funnels collapsed one after the other as the ship rapidly sank. By the time the stern was out of the water, the bow had already slammed into the seabed. As Britannic's length was greater than the depth of the water, the impact caused major structural damage to the bow before she slipped completely beneath the waves at 09:07, 55 minutes after the explosion.[55] Violet Jessop (who was one of the survivors of the Titanic, and had also been on board when the Olympic collided with HMS Hawke) described the last seconds:[57]

When the Britannic came to rest, she became the largest ship lost in the First World War and the world's largest sunken passenger ship.[58] Rescue  Compared to Titanic, the rescue of Britannic was facilitated by three factors: The water temperature was higher (20 °C (68 °F)[60] compared to −2 °C (28 °F)[61] for Titanic), more lifeboats were available (35 were successfully launched and stayed afloat[62] compared to Titanic's 20[63]), and help was closer (it arrived less than two hours after first distress call[62] compared to three and a half hours for Titanic[64]). The first to arrive on the scene were fishermen from Kea on their caïque, who picked many survivors from the water.[65] At 10:00, HMS Scourge sighted the first lifeboats and 10 minutes later stopped and picked up 339 survivors. Armed boarding steamer HMS Heroic had arrived some minutes earlier and picked up 494.[66] Some 150 had made it to Korissia, Kea, where surviving doctors and nurses from Britannic were trying to save the injured, using aprons and pieces of lifebelts to make dressings. A little barren quayside served as their operating room.[citation needed] Scourge and Heroic had no deck space for more survivors, and they left for Piraeus signalling the presence of those remaining at Korissia. HMS Foxhound arrived at 11:45 and, after sweeping the area, anchored in the small port at 13:00 to offer medical assistance and take on board the remaining survivors.[66] At 14:00 the light cruiser HMS Foresight arrived. Foxhound departed for Piraeus at 14:15 while Foresight remained to arrange the burial on Kea of RAMC Sergeant William Sharpe, who had died of his injuries. Another two survivors died on the Heroic and one on the French tug Goliath. The three were buried with military honours in the Piraeus Naval and Consular Cemetery.[67] The last fatality was G. Honeycott, who died at the Russian Hospital at Piraeus shortly after the funerals.[citation needed] In total, out of the 1,066 people on board, 1,036 people survived the sinking. Thirty people lost their lives in the disaster[68] but only five were buried; others were not recovered and are honoured on memorials in Thessaloniki (the Mikra Memorial) and London. Another 38 were injured (18 crew, 20 RAMC).[69] Survivors were accommodated in the warships that were anchored at the port of Piraeus while nurses and officers were hosted in separate hotels at Phaleron. Many Greek citizens and officials attended the funerals. Survivors were sent home and few arrived in the United Kingdom before Christmas.[70] In November 2006, Britannic researcher Michail Michailakis discovered that one of the 45 unidentified graves in the New British Cemetery in the town of Hermoupolis on the island of Syros contained the remains of a soldier collected from the church of Ag. Trias at Livadi (the former name of Korissia). Maritime historian Simon Mills contacted the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Further research established that this soldier was a Britannic casualty and his remains had been registered in October 1919 as belonging to a certain "Corporal Stevens".[71] When the remains were moved to the new cemetery at Syros in June 1921, it was found that there was no record relating this name with the loss of the ship, and the grave was registered as unidentified. Mills provided evidence that this man could be Sergeant Sharpe and the case was considered by the Service Personnel and Veterans Agency.[71] A new headstone for Sharpe was erected and the CWGC has updated its database.[72] Visualised as an ocean linerThe plan of Britannic showed that she was intended to be more luxurious than her sister ships in order to compete with SS Imperator, SS Vaterland and RMS Aquitania. Enough cabins were provided for passengers divided into three classes. The White Star Line anticipated a considerable change in its customer base. Thus, the quality of the Third Class (intended for migrants) was lowered when compared to that of her sisters, while the quality of the Second Class increased. In addition, the number of crew planned was increased from about 860 – 880 onboard Olympic and Titanic to 950 aboard Britannic.[73] The quality of the First Class was also improved. Children began to appear as part of the clientele that needed to be satisfied, and thus a playroom for them was built on the boat deck.[74] Similar to her two sister ships, the first class amenities included the Grand Staircase, but Britannic's amenities were more sumptuous, with worked balustrades, decorative panels and a pipe organ.[75] The A Deck of the ship was devoted in its entirety to the First Class, being fitted with a salon, two veranda cafes, a smoking room and a reading room.[76] The B Deck included a hair salon, post office, and redesigned deluxe Parlour Suites, dubbed Saloons in the Builder's Plans.[77] The most important addition was that of individual bathrooms in almost every First Class cabin, which would have been a first on an ocean liner. Aboard the Olympic and Titanic, most passengers had to use public bathrooms.[78] These facilities were installed but were soon removed because the ship was converted to a hospital ship and were never re-installed because the ship sank before she could enter transatlantic service, so the planned facilities were either cancelled, destroyed, reused on other vessels, like the Olympic or Majestic, or just never used.[30] Of these accessories, only a large staircase and a children's playroom remained installed. Under the glass dome was a white wall above the first-class staircase instead of a clock and a large painting.  Pipe organA Welte philharmonic organ was planned to be installed on board Britannic but because of the outbreak of war, the instrument never made its way to Belfast from Germany.[30] After the war, it was not claimed by Harland and Wolff since Britannic sank before she could have ever entered transatlantic service. It also was not installed on Olympic or Majestic since White Star Line did not want it. For a long time, it was thought that the organ was lost or destroyed.[30] In April 2007, the restorers of a Welte organ, now in the Museum für Musikautomaten in Seewen, Switzerland, detected that the main parts of the instrument were signed by the German organ builders with "Britanik".[79] A photograph of a drawing in a company prospectus, found in the Welte-legacy in the Augustiner Museum in Freiburg, proved that this was the organ intended for Britannic. It was found that Welte had first sold the organ to a private owner in Stuttgart instead. Later, in 1937 it had been transferred to a company's concert hall in Wipperfürth, where it was eventually acquired by the founder of the Swiss Museum of Music Automatons in 1969. At the time, the museum was still unaware of the organ's original history.[80][81] The museum maintains the organ in working condition and it is still used for fully automated and manual performances. WreckThe wreck's location off the coast of Greece The wreck of HMHS Britannic is at 37°42′05″N 24°17′02″E / 37.70139°N 24.28389°E in about 400 feet (122 m) of water.[4] It was discovered on 3 December 1975 by Jacques Cousteau, who explored it.[82][73] In filming the expedition, Cousteau also held conference on camera with several surviving personnel from the ship including Sheila MacBeth Mitchell, a survivor of the sinking.[83] In 1976, Cousteau entered the wreck with his divers for the first time.[84] He expressed the opinion that the ship had been sunk by a single torpedo, basing this opinion on the damage to her plates.[85] The giant liner lies on her starboard side relatively intact, hiding the large hole that was torn open by the mine. There is a huge hole just beneath the forward well deck. The bow is heavily deformed and attached to the rest of the hull only by some pieces of C-Deck. The crew's quarters in the forecastle were found to be in good shape with many details still visible. The holds were found empty.[84] The forecastle machinery and the two cargo cranes in the forward well deck are well preserved. The foremast is bent and lies on the seabed near the wreck with the crow's nest still attached. The bell, thought to be lost, was found in a dive in 2019, having fallen from the mast and is now lying directly below the crow's nest on the seabed. Funnel number 1 was found a few metres from the Boat Deck. Funnel numbers two, three, and four were found in the debris field (located off the stern).[84] Pieces of coal lie beside the wreck.[86] In mid-1995, in an expedition filmed by NOVA, Dr Robert Ballard, best known for having discovered the wrecks of Titanic in 1985, and the German battleship Bismarck in 1989, visited the wreck, using advanced side-scan sonar. Images were obtained from remotely controlled vehicles, but the wreck was not penetrated. Ballard found all the ship's funnels in surprisingly good condition. Attempts to find mine anchors failed.[87] In August 1996, the wreck was bought by Simon Mills, who has written two books about the ship: Britannic – The Last Titan and Hostage To Fortune.[88] In November 1997, an international team of divers led by Kevin Gurr used open-circuit trimix diving techniques to visit and film the wreck in the newly available DV digital video format.[87] In September 1998, another team of divers made an expedition to the wreck.[89][90] Using diver propulsion vehicles, the team made more man-dives to the wreck and produced more images than ever before, including video of four telegraphs, a helm and a telemotor on the captain's bridge.[91] In 1999 GUE divers acclimated to cave diving and ocean discovery led the first dive expedition to include extensive penetration into Britannic. Video of the expedition was broadcast by National Geographic, BBC, the History Channel and the Discovery Channel.[92] In September 2003, an expedition led by Carl Spencer dived into the wreck.[93] This was the first expedition to dive Britannic where all the bottom divers were using closed circuit rebreathers (CCR). Diver Leigh Bishop brought back some of the first photographs from inside the wreck and his diver partner Rich Stevenson found that several watertight doors were open. It has been suggested that this was because the mine strike coincided with the change of watches. Alternatively, the explosion may have distorted the doorframes. A number of mine anchors were located off the wreck by sonar expert Bill Smith, confirming the German records of U-73 that Britannic was sunk by a single mine and the damage was compounded by open portholes and watertight doors. Spencer's expedition was broadcast extensively across the world for many years by National Geographic and the UK's Channel 5.[94] In 2006, an expedition, funded and filmed by the History Channel, brought together fourteen skilled divers to help determine what caused the quick sinking of Britannic.[94] After preparation the crew dived on the wreck site on 17 September. Time was cut short when silt was kicked up, causing zero visibility conditions, and the two divers narrowly escaped with their lives. One last dive was to be attempted on Britannic's boiler room, but it was discovered that photographing this far inside the wreck would lead to violating a permit issued by the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, a department within the Greek Ministry of Culture. Partly because of a barrier in languages, a last-minute plea was turned down by the department. The expedition was unable to determine the cause of the rapid sinking, but hours of footage were filmed and important data was documented. The Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities later recognised the importance of this mission and extended an invitation to revisit the wreck under less stringent rules. On 24 May 2009, Carl Spencer, drawn back to his third underwater filming mission of Britannic, died in Greece due to equipment difficulties while filming the wreck for National Geographic.[95] In 2012, on an expedition organised by Alexander Sotiriou and Paul Lijnen, divers using rebreathers installed and recovered scientific equipment used for environmental purposes, to determine how fast bacteria are eating Britannic's iron compared to Titanic.[96] On 29 September 2019, a British technical diver, Tim Saville, died during a 120 m / 393 ft dive on Britannic's wreck.[97] LegacyHaving her career cut short in wartime, never having entered commercial service, and having had few victims, Britannic did not experience the same notoriety as her sister ship Titanic. After being largely forgotten by the public, she finally gained fame when her wreck was discovered.[98] Her name was reused by the White Star Line when it put MV Britannic into service in 1930. That ship was the last to fly the flag of the company when it retired in 1960.[99] After Germany capitulated at the end of the First World War followed by the Treaty of Versailles, it handed over some of its ocean liners as war reparations, two of which were given to the company. The first, the Bismarck, renamed Majestic, replaced the Britannic. The second, the Columbus, renamed the Homeric, compensated for other ships lost in the conflict.[100] The last survivor, George Perman, died on 24 May 2000, just short of his 100th birthday. At the time of the sinking, he was a 15-year-old Scout working on Britannic, and the youngest person onboard the ship.[101][102] In popular cultureA fictionalised version of the sinking of the ship was dramatised in a 2000 television film Britannic that featured Edward Atterton, Amanda Ryan, Jacqueline Bisset and John Rhys-Davies, depicting a German agent sabotaging the ship, due to it secretly carrying munitions.[citation needed] A BBC2 documentary, Titanic's Tragic Twin – the Britannic Disaster, was broadcast on 5 December 2016; presented by Kate Humble and Andy Torbet, it used up-to-date underwater film of the wreck and spoke to relatives of survivors.[103] The historical docudrama The Mystery Of The Britannic was released in 2017, in which the maritime explorer Richard Kohler investigates the ship's last voyage.[citation needed] Alma Katsu's 2020 novel The Deep was set partly on the Britannic, and on its sister ship the Titanic, and centred around the sinking of both ships.[104] The Gigantic, the apparent setting of the 2009 escape-room game Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors, references the Britannic as a sister ship of the Titanic retrofitted as a hospital ship.[105][non-primary source needed] PostcardsPostcards of Britannic References

Bibliography

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Britannic (ship, 1915).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||