|

HMS Edinburgh (1882)

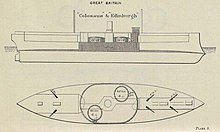

HMS Edinburgh was an ironclad battleship of the Colossus class which served in the Royal Navy of the Victorian era. She was the sister ship of HMS Colossus, being started before her but being completed after. Edinburgh was the first British battleship since HMS Warrior, launched in 1860, to carry breech-loading artillery as part of her main armament. Warrior had been equipped with 10 110-pounder Armstrong breech-loading guns, which had not proved satisfactory, to complement her 26 muzzle-loaders. Edinburgh's guns were carried in two turrets positioned near the centre of the ship, and the turrets were mounted en echelon. It was expected that, by mounting the turrets in this way, at least one gun from each turret could fire fore and aft along the keel line, and all four guns could fire on broadside bearings; it was intended that every part of the horizon could be covered by at least two guns. In practice it was found that firing too close to the keel line caused unacceptable blast damage to the superstructure, and cross-deck firing similarly caused damage to the deck. Before Edinburgh the positioning of the conning tower in British ironclads had produced a variety of solutions; the difficulty was that the two important factors involved, maximum protection and maximum visibility, were essentially mutually incompatible. In this ship the conning tower was positioned forward of the foremast for good all-round vision; the chart-house was, however, placed on its roof, and the whole area surrounded by small guns, stanchions and other obstructions to the view. The problem was not solved until the political will to build larger ships in turn allowed more space for command facilities. DesignThe design for the Colossus class was based on the earlier Ajax class of turret ships, but with numerous improvements. They were larger, slightly faster, and had improved handling characteristics and significantly more powerful armament. Instead of older muzzle-loading guns, the Colossus class reintroduced breech-loading guns to Royal Navy service, along with a secondary battery, a feature not included in older ironclads. The new ship also incorporated compound armour instead of the traditional wrought iron armour used in earlier vessels. In addition, the ships' hulls were constructed with steel, not iron.[1]  Edinburgh was 325 feet (99.1 m) long between perpendiculars and had a beam of 68 ft (21 m) and a draught of 25 ft 9 in (7.85 m). She displaced 9,420 long tons (9,570 t). The ship had a long, raised fore and sterncastle connected by a hurricane deck. The superstructure consisted of a small conning tower atop the forecastle. She had a crew of 396 officers and ratings. Her propulsion system consisted of two 3-cylinder marine steam engines powered by ten coal-fired fire-tube boilers, which were vented through a single large funnel located amidships. Her engines provided a top speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) at 6,808 indicated horsepower (5,077 kW), exceeding the contracted performance by 2 knots (3.7 km/h; 2.3 mph) and 800 ihp (600 kW).[1][2] The ship was armed with a main battery of four BL 12-inch (305 mm) breech-loading guns in twin-gun turrets, which were placed en echelon amidships, fore and aft of the funnel. Edinburgh also carried a secondary battery of five BL 6-inch (152 mm) breech-loading guns. These were carried in individual pivot mounts, one on either side of the forward superstructure, another pair abreast the aft superstructure, and the final gun on the upper deck at the stern. She also carried four QF 6-pounder guns for defence against torpedo boats. As was customary for capital ships of the period, she was equipped with a pair of 14-inch (356 mm) torpedo tubes.[1] Edinburgh's armoured citadel was 14 to 18 inches (356 to 457 mm) thick on the sides and reduced to 13 to 16 in (330 to 406 mm) on its rounded bulkheads, where it was intended to deflect incoming projectiles. It was 123 ft (37 m) long, slightly more than a third of the ship's length, and covered the ship's ammunition magazines and propulsion machinery spaces. She carried a protective deck that was 2.5 to 3 in (64 to 76 mm) thick and sloped downward at the sides. Above and below the deck, coal storage spaces were arranged to provide additional defence against gunfire. The main battery turrets had 14 to 16 in of armour plate, and the conning tower had 14 in sides.[1] Service history The keel for Edinburg was laid down on 20 March 1879 at the Pembroke Dockyard, and her completed hull was launched on 18 March 1882. Fitting-out work was completed the following year, less her armament, allowing the ship to begin sea trials on 11 September that continued into 1884. These trials included tests to determine the ship's stability and fuel consumption. Problems with delivery of her armament delayed her completion significantly, and Edinburg was not completed until 8 July 1887.[1][3] She entered service in time to join the fleet for the Golden Jubilee Fleet Review held on 25 July for Queen Victoria.[4] Edinburg was thereafter assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet, where she served until 1894, when she was reduced to service as a coastguard ship at Hull and later Queensferry from 1894 to 1897.[1] Edinburgh participated in the fleet manoeuvres in August 1894, serving as part of the "Blue" fleet commanded by Rear Admiral Edward Seymour. She was assigned to Group 1 of the fleet, which also included her sister ship Colossus, the recently completed pre-dreadnought battleship Barfleur, and the ironclads Alexandra, Benbow, and Inflexible, and the protected cruiser St George. The exercises lasted around 36 hours before the results were decided in favour of "Blue" fleet. During the manoeuvres, Edinburgh was judged to have been disabled by coastal artillery at Belfast.[5] In August 1895, Edinburgh was again reactivated to take part in the annual fleet manoeuvres as part of the Reserve Fleet. At that time, the capital ships assigned to the fleet included Colossus, Alexandra, Benbow, and the ironclad Dreadnought.The ships were mobilised at Torbay in early August, went to sea on the 8th, and carried out various training exercises, including shooting practice and tactical manoeuvres, before returning to port on 20 August.[6] During the 1896 fleet manoeuvres, Edinburgh, Colossus, Alexandra, and Benbow were joined by the old ironclad Sultan in Fleet C, one of four organized for the exercises. Fleet C operated in concert with Fleet D, again commanded by Seymour. He was given the objective to combine his fleets and either defeat the strong A and B fleets in detail or to reach the fortified port of Lough Swilly. The ships went to sea on 24 July and by the morning of 30 July, Seymour had succeeded in uniting his fleets but failed to bring Fleet A to battle, and therefore took his ships to Lough Swilly.[7] She was then placed in reserve from 1897 until 1899.[1] During this period, on 26 June 1897, Edinburgh was present for the fleet review held for Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee.[8] The ship once again participated in the fleet manoeuvres in 1897; that year, the Reserve Fleet was divided into two divisions for its own exercises apart from the active Channel Fleet. Edinburgh was assigned to the 2nd Division, along with the ironclads Sans Pareil and Thunderer and the armoured cruisers Warspite and Aurora. The exercises lasted from 7 to 11 July.[9] Edinburg was then refitted in 1898, with work completed the following year.[10] Later that year, she returned to service to act as a tender for Wildfire at Sheerness, a role she filled until 1905.[1] She participated in the fleet manoeuvres in late July and early August 1900, which ended inconclusively after ten days.[11] She became a flagship on 1 November 1901, when Vice-Admiral Albert Hastings Markham hoisted his flag on becoming Commander-in-Chief, The Nore.[12] She took part in the fleet review held at Spithead on 16 August 1902 for the coronation of King Edward VII.[13] In 1908 she was converted for use as a target ship, being fitted with fully backed and supported modern armour plates; the intention was to test and measure the effect on these plates of oblique impact by armour-piercing shells filled with lyddite, the most potent explosive of the period. As a result of these trials, which revealed major shortcomings in British high-explosive shells, the Controller, Jellicoe, ordered that the design of these shells should be improved. He was shortly thereafter appointed in command of the British Atlantic Fleet, and this instruction was not carried out. At the Battle of Jutland many British armour-piercing shells either did not pierce German armour, or did so but failed to explode, because of this failing. Edinburg was ultimately sold to shipbreakers in 1910.[1] Notes

References

Further reading

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||