|

Hierarchy problem

In theoretical physics, the hierarchy problem is the problem concerning the large discrepancy between aspects of the weak force and gravity.[1] There is no scientific consensus on why, for example, the weak force is 1024 times stronger than gravity. Technical definitionA hierarchy problem[2] occurs when the fundamental value of some physical parameter, such as a coupling constant or a mass, in some Lagrangian is vastly different from its effective value, which is the value that gets measured in an experiment. This happens because the effective value is related to the fundamental value by a prescription known as renormalization, which applies corrections to it. Typically the renormalized value of parameters are close to their fundamental values, but in some cases, it appears that there has been a delicate cancellation between the fundamental quantity and the quantum corrections. Hierarchy problems are related to fine-tuning problems and problems of naturalness. Over the past decade[timeframe?] many scientists[3][4][5][6][7] argued that the hierarchy problem is a specific application of Bayesian statistics. Studying renormalization in hierarchy problems is difficult, because such quantum corrections are usually power-law divergent, which means that the shortest-distance physics are most important. Because we do not know the precise details of the quantum gravity, we cannot even address how this delicate cancellation between two large terms occurs. Therefore, researchers are led to postulate new physical phenomena that resolve hierarchy problems without fine-tuning. Overview

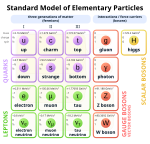

Suppose a physics model requires four parameters to produce a very high-quality working model capable of generating predictions regarding some aspect of our physical universe. Suppose we find through experiments that the parameters have values: 1.2, 1.31, 0.9 and a value near 4×1029. One might wonder how such figures arise. But in particular, might be especially curious about a theory where three values are close to one, and the fourth is so different; in other words, the huge disproportion we seem to find between the first three parameters and the fourth. We might also wonder if one force is so much weaker than the others that it needs a factor of 4×1029 to allow it to be related to them in terms of effects, how did our universe come to be so exactly balanced when its forces emerged? In current particle physics, the differences between some parameters are much larger than this, so the question is even more noteworthy. One answer given by philosophers is the anthropic principle. If the universe came to exist by chance, and perhaps vast numbers of other universes exist or have existed, then life capable of physics experiments only arose in universes that, by chance, had very balanced forces. All of the universes where the forces were not balanced did not develop life capable of asking this question. So if lifeforms like human beings are aware and capable of asking such a question, humans must have arisen in a universe having balanced forces, however rare that might be.[8][9] A second possible answer is that there is a deeper understanding of physics that we currently do not possess. There might be parameters that we can derive physical constants from that have less unbalanced values, or there might be a model with fewer parameters.[citation needed] Examples in particle physicsHiggs massIn particle physics, the most important hierarchy problem is the question that asks why the weak force is 1024 times as strong as gravity.[10] Both of these forces involve constants of nature, the Fermi constant for the weak force and the Newtonian constant of gravitation for gravity. Furthermore, if the Standard Model is used to calculate the quantum corrections to Fermi's constant, it appears that Fermi's constant is surprisingly large and is expected to be closer to Newton's constant unless there is a delicate cancellation between the bare value of Fermi's constant and the quantum corrections to it.  More technically, the question is why the Higgs boson is so much lighter than the Planck mass (or the grand unification energy, or a heavy neutrino mass scale): one would expect that the large quantum contributions to the square of the Higgs boson mass would inevitably make the mass huge, comparable to the scale at which new physics appears unless there is an incredible fine-tuning cancellation between the quadratic radiative corrections and the bare mass. The problem cannot even be formulated in the strict context of the Standard Model, for the Higgs mass cannot be calculated. In a sense, the problem amounts to the worry that a future theory of fundamental particles, in which the Higgs boson mass will be calculable, should not have excessive fine-tunings. Theoretical solutionsThere have been many proposed solutions by many experienced physicists. SupersymmetrySome physicists believe that one may solve the hierarchy problem via supersymmetry. Supersymmetry can explain how a tiny Higgs mass can be protected from quantum corrections. Supersymmetry removes the power-law divergences of the radiative corrections to the Higgs mass and solves the hierarchy problem as long as the supersymmetric particles are light enough to satisfy the Barbieri–Giudice criterion.[11] This still leaves open the mu problem, however. The tenets of supersymmetry are being tested at the LHC, although no evidence has been found so far for supersymmetry. Each particle that couples to the Higgs field has an associated Yukawa coupling . The coupling with the Higgs field for fermions gives an interaction term , with being the Dirac field and the Higgs field. Also, the mass of a fermion is proportional to its Yukawa coupling, meaning that the Higgs boson will couple most to the most massive particle. This means that the most significant corrections to the Higgs mass will originate from the heaviest particles, most prominently the top quark. By applying the Feynman rules, one gets the quantum corrections to the Higgs mass squared from a fermion to be:

The is called the ultraviolet cutoff and is the scale up to which the Standard Model is valid. If we take this scale to be the Planck scale, then we have the quadratically diverging Lagrangian. However, suppose there existed two complex scalars (taken to be spin 0) such that:

(the couplings to the Higgs are exactly the same). Then by the Feynman rules, the correction (from both scalars) is:

(Note that the contribution here is positive. This is because of the spin-statistics theorem, which means that fermions will have a negative contribution and bosons a positive contribution. This fact is exploited.) This gives a total contribution to the Higgs mass to be zero if we include both the fermionic and bosonic particles. Supersymmetry is an extension of this that creates 'superpartners' for all Standard Model particles.[12] ConformalWithout supersymmetry, a solution to the hierarchy problem has been proposed using just the Standard Model. The idea can be traced back to the fact that the term in the Higgs field that produces the uncontrolled quadratic correction upon renormalization is the quadratic one. If the Higgs field had no mass term, then no hierarchy problem arises. But by missing a quadratic term in the Higgs field, one must find a way to recover the breaking of electroweak symmetry through a non-null vacuum expectation value. This can be obtained using the Weinberg–Coleman mechanism with terms in the Higgs potential arising from quantum corrections. Mass obtained in this way is far too small with respect to what is seen in accelerator facilities and so a conformal Standard Model needs more than one Higgs particle. This proposal has been put forward in 2006 by Krzysztof Antoni Meissner and Hermann Nicolai[13] and is currently under scrutiny. But if no further excitation is observed beyond the one seen so far at LHC, this model would have to be abandoned. Extra dimensionsNo experimental or observational evidence of extra dimensions has been officially reported. Analyses of results from the Large Hadron Collider severely constrain theories with large extra dimensions.[14] However, extra dimensions could explain why the gravity force is so weak, and why the expansion of the universe is faster than expected.[15] If we live in a 3+1 dimensional world, then we calculate the gravitational force via Gauss's law for gravity:

which is simply Newton's law of gravitation. Note that Newton's constant G can be rewritten in terms of the Planck mass.

If we extend this idea to δ extra dimensions, then we get:

where is the 3+1+-dimensional Planck mass. However, we are assuming that these extra dimensions are the same size as the normal 3+1 dimensions. Let us say that the extra dimensions are of size n ≪ than normal dimensions. If we let r ≪ n, then we get (2). However, if we let r ≫ n, then we get our usual Newton's law. However, when r ≫ n, the flux in the extra dimensions becomes a constant, because there is no extra room for gravitational flux to flow through. Thus the flux will be proportional to nδ because this is the flux in the extra dimensions. The formula is:

which gives:

Thus the fundamental Planck mass (the extra-dimensional one) could actually be small, meaning that gravity is actually strong, but this must be compensated by the number of the extra dimensions and their size. Physically, this means that gravity is weak because there is a loss of flux to the extra dimensions. This section is adapted from Quantum Field Theory in a Nutshell by A. Zee.[16] Braneworld modelsIn 1998 Nima Arkani-Hamed, Savas Dimopoulos, and Gia Dvali proposed the ADD model, also known as the model with large extra dimensions, an alternative scenario to explain the weakness of gravity relative to the other forces.[17][18] This theory requires that the fields of the Standard Model are confined to a four-dimensional membrane, while gravity propagates in several additional spatial dimensions that are large compared to the Planck scale.[19] In 1998–99 Merab Gogberashvili published on arXiv (and subsequently in peer-reviewed journals) a number of articles where he showed that if the Universe is considered as a thin shell (a mathematical synonym for "brane") expanding in 5-dimensional space then it is possible to obtain one scale for particle theory corresponding to the 5-dimensional cosmological constant and Universe thickness, and thus to solve the hierarchy problem.[20][21][22] It was also shown that four-dimensionality of the Universe is the result of a stability requirement since the extra component of the Einstein field equations giving the localized solution for matter fields coincides with one of the conditions of stability. Subsequently, there were proposed the closely related Randall–Sundrum scenarios which offered their solution to the hierarchy problem. UV/IR mixingIn 2019, a pair of researchers proposed that IR/UV mixing resulting in the breakdown of the effective quantum field theory could resolve the hierarchy problem.[23] In 2021, another group of researchers showed that UV/IR mixing could resolve the hierarchy problem in string theory.[24] Cosmological constantIn physical cosmology, current observations in favor of an accelerating universe imply the existence of a tiny, but nonzero cosmological constant. This problem, called the cosmological constant problem, is a hierarchy problem very similar to that of the Higgs boson mass problem, since the cosmological constant is also very sensitive to quantum corrections, but it is complicated by the necessary involvement of general relativity in the problem. Proposed solutions to the cosmological constant problem include modifying and/or extending gravity,[25][26][27] adding matter with unvanishing pressure,[28] and UV/IR mixing in the Standard Model and gravity.[29][30] Some physicists have resorted to anthropic reasoning to solve the cosmological constant problem,[31] but it is disputed whether anthropic reasoning is scientific.[32][33] See alsoWikiquote has quotations related to Hierarchy problem. References

|

![{\displaystyle \Delta m_{\rm {H}}^{2}=-{\frac {\left|\lambda _{f}\right|^{2}}{8\pi ^{2}}}[\Lambda _{\mathrm {UV} }^{2}+\dots ].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/465fbddb9c0ae7cc1981dd4104fd93fa4e2ddeed)

![{\displaystyle \Delta m_{\rm {H}}^{2}=2\times {\frac {\lambda _{S}}{16\pi ^{2}}}[\Lambda _{\mathrm {UV} }^{2}+\dots ].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3adddf1018d016c394050a72c5192e833a75be31)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathbf {g} (\mathbf {r} )&=-m{\frac {\mathbf {e_{r}} }{M_{\mathrm {Pl} _{3+1+\delta }}^{2+\delta }r^{2}n^{\delta }}}\\[2pt]-m{\frac {\mathbf {e_{r}} }{M_{\mathrm {Pl} }^{2}r^{2}}}&=-m{\frac {\mathbf {e_{r}} }{M_{\mathrm {Pl} _{3+1+\delta }}^{2+\delta }r^{2}n^{\delta }}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d3ababf7759a7083ff9cae75dc3403901ea9f9fd)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {1}{M_{\mathrm {Pl} }^{2}r^{2}}}&={\frac {1}{M_{\mathrm {Pl} _{3+1+\delta }}^{2+\delta }r^{2}n^{\delta }}}\\[2pt]\implies \quad M_{\mathrm {Pl} }^{2}&=M_{\mathrm {Pl} _{3+1+\delta }}^{2+\delta }n^{\delta }\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7ad31158f035dcb0ca51f15d1a98aba2b67b4b5e)