|

Hispaniola

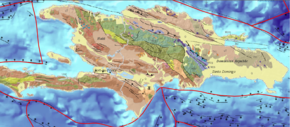

Hispaniola (/ˌhɪspənˈjoʊlə/,[5][6][7] also UK: /-pænˈ-/)[8][9][10][11] is an island between Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and the second-largest by land area, after Cuba. The 76,192-square-kilometre (29,418 sq mi) island is divided into two separate sovereign countries: the Spanish-speaking Dominican Republic (48,445 km2 (18,705 sq mi) to the east and the French and Haitian Creole–speaking Haiti (27,750 km2 (10,710 sq mi) to the west. The only other divided island in the Caribbean is Saint Martin, which is shared between France (Saint Martin) and the Netherlands (Sint Maarten). Hispaniola is the site of one of the first European forts in the Americas, La Navidad (1492–1493), as well as the first settlement La Isabela (1493–1500), and the first permanent settlement, the current capital of the Dominican Republic, Santo Domingo (est. 1498). These settlements were founded successively during each of Christopher Columbus's first three voyages.[12][13][14][15] The Spanish Empire controlled the entire island of Hispaniola from the 1490s until the 17th century, when French pirates began establishing bases on the western side of the island. The official name was La Española, meaning "The Spanish (Island)". It was also called Santo Domingo, after Saint Dominic. EtymologyThe island was called various names by its native people, the Taíno. The Taino had no written language, hence, historical evidence for these names comes through three European historians: the Italian Peter Martyr d'Anghiera, and the Spaniards Bartolomé de las Casas and Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo. Based on a comprehensive survey and map prepared by Andrés de Morales in 1508, Martyr reported that the island as a whole was called Quizquella (or Quisqueya) and Ayiti referred to a rugged mountainous region on the western end of the island.[16] Diego Álvarez Chanca, a physician on Columbus's second voyage, also noted that "Ayiti" or Haïti was the easternmost province of the island, an area in the Dominican Republic called "Los Haitises" national park. On the other hand, Oviedo and Las Casas both recorded that the entire island was called Ayiti by the Taíno.[17] When Columbus took possession of the island in 1492, he named it Insula Hispana in Latin[18] and La Isla Española in Spanish,[19] both meaning "the Spanish island". Las Casas shortened the name to Española, and when Peter Martyr detailed his account of the island in Latin, he rendered its name as Hispaniola.[19] Due to Taíno, Spanish and French influences on the island, historically the whole island was often referred to as Haïti, Hayti, Santo Domingo, or Saint-Domingue.[20] Martyr's literary work was translated into English and French soon after being written, the name Hispaniola became the most frequently used term in English-speaking countries for the island in scientific and cartographic works. In 1918, the United States occupation government, led by Harry Shepard Knapp, obliged the use of the name Hispaniola on the island, and recommended the use of that name to the National Geographic Society.[21] The name "Haïti" was adopted by Haitian revolutionary Jean-Jacques Dessalines in 1804, as the official name of independent Saint-Domingue, in tribute to the Amerindian predecessors. It was also adopted as the official name of independent Santo Domingo, as the Republic of Spanish Haiti, a state that existed from November 1821 until its annexation by Haiti in February 1822.[22][23] HistoryPre-ColumbianThe Pomier Caves are a series of 55 caves located north of San Cristóbal in the Dominican Republic. They contain the largest collection of 2,000-year-old rock art in the Caribbean, primarily made by the Taíno people, but also the Carib people and the Igneri. The Archaic Age people arrived from mainland Central America or northern South America about 6,000 years ago, and are thought to have practised a largely hunter-gatherer lifestyle. During the 1st millennium BC, the Arawakan-speaking ancestors of the Taino people began to migrate into the Caribbean. Unlike the Archaic peoples, they practiced the intensive production of pottery and agriculture. The earliest evidence of the ancestors of the Taino people on Hispaniola is the Ostionoid culture, which dates to around 600 AD.[24] The Taino represented the dominant group on the island during the period of European contact.[25] Each society on the island was a small independent kingdom with a lead known as a cacique.[26] In 1492, which is considered the peak of the Taíno, there were five different kingdoms on the island,[25] the Xaragua, Higuey (Caizcimu), Magua (Huhabo), Ciguayos (Cayabo or Maguana), and Marien (Bainoa).[26] Many distinct Taíno languages also existed in this time period.[27] There is still heated debate over the population of Taíno people on the island of Hispaniola in 1492, but estimates range from no more than a few tens of thousands, according to a 2020 genetic analysis,[28][29] to upwards of 750,000.[30] A Taíno home consisted of a circular building with woven straw and palm leaves as covering.[26] Most individuals slept in fashioned hammocks, but grass beds were also used.[25] The cacique lived in a different structure with larger rectangular walls and a porch.[26] The Taíno village also had a flat court used for ball games and festivals.[26] Religiously, the Taíno people were polytheists, and their gods were called Zemí.[26] Religious worship and dancing were common, and medicine men or priests also consulted the Zemí for advice in public ceremonies.[26] For food, the Taíno relied on meat and fish as a primary source for protein.[31] On the island they hunted small mammals, but also snakes, worms, and birds. In lakes and in the sea they were able to catch ducks and turtles.[26] The Taíno also relied on agriculture as a primary food source.[31] The indigenous people of Hispaniola raised crops in a conuco, which is a large mound packed with leaves and fixed crops to prevent erosion.[26] Some common agricultural goods were cassava, maize, squash, beans, peppers, peanuts, cotton, and tobacco, which was used as an aspect of social life and religious ceremonies.[26]  The Taíno people traveled often and used hollowed canoes with paddles when on the water for fishing or for migration purposes,[26] and upwards of 100 people could fit into a single canoe.[25] The Taíno came frequently in contact with the Caribs, another indigenous tribe.[26] The Taíno people had to defend themselves using bows and arrows with poisoned tips and some war clubs.[26] When Columbus landed on Hispaniola, many Taíno leaders wanted protection from the Caribs.[26] Post-Columbian Christopher Columbus first landed at Hispaniola on December 6, 1492, at a small bay he named San Nicolas, now called Môle-Saint-Nicolas on the north coast of present-day Haiti. He was welcomed in a friendly fashion by the indigenous people known as the Taíno. Trading with the natives yielded more gold than they had come across previously on the other Caribbean islands and Columbus was led to believe that much more gold would be found inland. Before he could explore further, his flagship, the Santa Maria, ran aground and sank in the bay on December 24. With only two smaller ships remaining for the voyage home, Columbus built a fortified encampment, La Navidad, on the shore and left behind 21 crewman to await his return the following year.[32] Colonization began in earnest the following year when Columbus brought 1,300 men to Hispaniola in November 1493 with the intention of establishing a permanent settlement. They found the encampment at Navidad had been destroyed and all the crewmen left behind killed by the natives. Columbus decided to sail east in search of a better site to found a new settlement. In January 1494 they established La Isabela in present-day Dominican Republic.[33]  In 1496, the town of Nueva Isabela was founded. After being destroyed by a hurricane, it was rebuilt on the opposite side of the Ozama River and called Santo Domingo. It is the oldest permanent European settlement in the Americas.[34] The island had an important role in the establishment of Latin American colonies for decades to come. Due to its strategic location, it was the military stronghold of conquistadors of the Spanish Empire, serving as a headquarters for the further colonial expansion into the Americas. The colony was a meeting point of European explorers, soldiers, and settlers who brought with them the culture, architecture, laws, and traditions of the Old World. Spaniards imposed a harsh regime of forced labor and enslavement of the Taínos, as well as redirection of their food production and labor to Spaniards. This had a devastating impact on both mortality and fertility of the Taíno population over the first quarter century.[35] Colonial administrators and Dominican and Hieronymite friars observed that the search for gold and agrarian enslavement through the encomienda system were deciminating the indigenous population.[35] Demographic data from two provinces in 1514 shows a low birth rate, consistent with a 3.5% annual population decline. In 1503, Spaniards began to bring enslaved Africans after a charter was passed in 1501, allowing the import of African slaves by Ferdinand and Isabel. The Spanish believed Africans would be more capable of performing physical labor. From 1519 to 1533, the indigenous uprising known as Enriquillo's Revolt, after the Taíno cacique who led them, ensued, resulting from escaped African slaves on the island (maroons) possibly working with the Taíno people.[36] Precious metals played a large role in the history of the island after Columbus's arrival. One of the first inhabitants Columbus came across on this island was "a girl wearing only a gold nose plug". Soon the Taínos were trading pieces of gold for hawk's bells[37] with their cacique declaring the gold came from Cibao. Traveling further east from Navidad, Columbus came across the Yaque del Norte River, which he named Río de Oro (River of Gold) because its "sands abound in gold dust".[38] On Columbus's return during his second voyage, he learned it was the chief Caonabo who had massacred his settlement at Navidad. While Columbus established a new settlement the village of La Isabela on Jan. 1494, he sent Alonso de Ojeda and 15 men to search for the mines of Cibao. After a six-day journey, Ojeda came across an area containing gold, in which the gold was extracted from streams by the Taíno people. Columbus himself visited the mines of Cibao on 12 March 1494. He constructed the Fort of Santo Tomás, present day Jánico, leaving Captain Pedro Margarit in command of 56 men.[38]: 119, 122–126 On 24 March 1495, Columbus with his ally Guacanagarix, embarked on a war of revenge against Caonabo, capturing him and his family while "killing many Indians and capturing others." Afterwards, "every person of fourteen years of age or upward was to pay a large hawk's bell[37] of gold dust", every three months, as "the Spaniards were sure there was more gold in the island than the natives had yet found, and were determined to make them dig it out."[37][38]: 149–150 16th century: gold, sugar and piratesGold mining using forced indigenous labor began early on Hispaniola. Miguel Díaz and Francisco de Garay discovered large gold nuggets on the lower Haina River in 1496. These San Cristobal mines were later known as the Minas Viejas mines. Then, in 1499, the first major discovery of gold was made in the cordillera central, which led to a mining boom. By 1501 Columbus's cousin, Giovanni Colombo, had discovered gold near Buenaventura. The deposits were later known as Minas Nuevas. Two major mining areas resulted, one along San Cristobal-Buenaventura, and another in Cibao within the La Vega-Cotuy-Bonao triangle, while Santiago de los Caballeros, Concepción, and Bonao became mining towns. The gold rush of 1500–1508 ensued, and Ovando expropriated the gold mines of Miguel Díaz and Francisco de Garay in 1504, as pit mines became royal mines for Ferdinand II of Aragon, who reserved the best mines for himself, though placers were open to private prospectors. King Ferdinand kept 967 natives in the San Cristóbal mining area, supervised by salaried miners.[39]: 68, 71, 78, 125–127 Under the royal governor Nicolás de Ovando, the indigenous people were forced to work in the gold mines. By 1503, the Spanish Crown legalized the allocation of private grants of indigenous labor to particular Spaniards for mining through the encomienda system. Once the indigenous were forced into mining far from their home villages, they suffered hunger and other difficult conditions. By 1508, the Taíno population of about 400,000 was reduced to 60,000, and by 1514, only 26,334 remained. About half resided in the mining towns of Concepción, Santiago, Santo Domingo, and Buenaventura. The repartimiento of 1514 accelerated emigration of the Spanish colonists, coupled with the exhaustion of the mines.[40][39]: 191–192 The first documented outbreak of smallpox, previously an Eastern hemisphere disease, occurred on Hispaniola in December 1518 among enslaved African miners.[35][41] Some scholars speculate that European diseases arrived before this date, but there is no compelling evidence for an outbreak.[35] The natives had no acquired immunity to European diseases, including smallpox.[42][43] By May 1519, as many as one-third of the remaining Taínos had died.[41] In the century following the Spanish arrival on Hispaniola, the Taíno population fell by up to 95% of the population,[44][45][46] out of a pre-contact population estimated from tens of thousands[29][46] to 8,000,000.[45] Many authors have described the treatment of Tainos in Hispaniola under the Spanish Empire as genocide.[47] Sugar cane was introduced to Hispaniola by settlers from the Canary Islands, and the first sugar mill in the New World was established in 1516, on Hispaniola.[48] The need for a labor force to meet the growing demands of sugar cane cultivation led to an exponential increase in the importation of slaves over the following two decades. The sugar mill owners soon formed a new colonial elite.[49] The first major slave revolt in the Americas occurred in Santo Domingo during 1521, when enslaved Muslims of the Wolof nation led an uprising in the sugar plantation of admiral Don Diego Colon, son of Christopher Columbus. Many of these insurgents managed to escape where they formed independent maroon communities in the south of the island. Beginning in the 1520s, the Caribbean Sea was raided by increasingly numerous French pirates. In 1541, Spain authorized the construction of Santo Domingo's fortified wall, and in 1560 decided to restrict sea travel to enormous, well-armed convoys. In another move, which would destroy Hispaniola's sugar industry, in 1561 Havana, more strategically located in relation to the Gulf Stream, was selected as the designated stopping point for the merchant flotas, which had a royal monopoly on commerce with the Americas. In 1564, the island's main inland cities Santiago de los Caballeros and Concepción de la Vega were destroyed by an earthquake. In the 1560s, English privateers joined the French in regularly raiding Spanish shipping in the Americas. 17th century: European skirmishes, division of the island and trade  By the early 17th century, Hispaniola and its nearby islands (notably Tortuga) became regular stopping points for Caribbean pirates. In 1606, the government of Philip III ordered all inhabitants of Hispaniola to move close to Santo Domingo, to fight against piracy. Rather than secure the island, his action meant that French, English, and Dutch pirates established their own bases on the less populated north and west coasts of the island. In 1625, French and English pirates arrived on the island of Tortuga, just off the northwest coast of Hispaniola, which was originally settled by a few Spanish colonists. The pirates were attacked in 1629 by Spanish forces commanded by Don Fadrique de Toledo, who fortified the island, and expelled the French and English. As most of the Spanish army left for the main island of Hispaniola to root out French colonists there, the French returned to Tortuga in 1630 and had constant battles for several decades. In 1654, the Spanish re-captured Tortuga for the last time.[50]  In 1655 the island of Tortuga was reoccupied by the English and French. In 1660 the English appointed a Frenchman as Governor who proclaimed the King of France, set up French colours, and defeated several English attempts to reclaim the island.[50] In 1665, French colonization of the island was officially recognized by King Louis XIV. The French colony was given the name Saint-Domingue. By 1670 a Welsh privateer named Henry Morgan invited the pirates on the island of Tortuga to set sail under him. They were hired by the French as a striking force that allowed France to have a much stronger hold on the Caribbean region. Consequently, the pirates never really controlled the island and kept Tortuga as a neutral hideout. The capital of the French Colony of Saint-Domingue was moved from Tortuga to Port-de-Paix on the mainland of Hispaniola in 1676. In 1680, new Acts of Parliament forbade sailing under foreign flags (in opposition to former practice). This was a major legal blow to the Caribbean pirates. Settlements were made in the Treaty of Ratisbon of 1684, signed by the European powers, that put an end to piracy. Most of the pirates after this time were hired out into the Royal services to suppress their former buccaneer allies. In the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, Spain formally ceded the western third of the island to France.[51][52] Saint-Domingue quickly came to overshadow the east in both wealth and population. Nicknamed the "Pearl of the Antilles", it became the most prosperous colony in the West Indies, with a system of human slavery used to grow and harvest sugar cane during a time when European demand for sugar was high. Slavery kept costs low and profit was maximized. It was an important port in the Americas for goods and products flowing to and from France and Europe. 18th century to 19th century: Independence European colonists often died young due to tropical fevers, as well as from violent slave resistance in the late eighteenth century. In 1791, during the French Revolution, a major slave revolt broke out on Saint-Domingue. When the French Republic abolished slavery in the colonies on February 4, 1794, it was a European first.[53] The ex-slave army joined forces with France in its war against its European neighbors. In the second 1795 Treaty of Basel (July 22), Spain ceded the eastern two-thirds of the island of Hispaniola, later to become the Dominican Republic. French settlers had begun to colonize some areas in the Spanish side of the territory.[citation needed] Under Napoleon, France reimposed slavery in most of its Caribbean islands in 1802 and sent an army to bring the island into full control. However, thousands of the French troops succumbed to yellow fever during the summer months, and more than half of the French army died because of disease.[54] After an extremely brutal war with atrocities committed on both sides, the French removed the surviving 7,000 troops in late 1803, and the surviving leaders of the Haitian Revolution declared western Hispaniola the new nation of independent Haiti in early 1804. France continued to rule Spanish Santo Domingo. In 1805, after renewed hostilities with the ruling French government in Santo Domingo, Haitian troops of General Jean Jacques Dessalines tried to conquer all of Hispaniola. He launched an invasion of Santo Domingo and sacked the towns of Santiago de los Caballeros and Moca, killing most of their residents, but news of a French fleet sailing towards Haiti forced the invading army to withdraw from the east, leaving it in French hands.    In 1808, a second revolution against France broke out on the island. Following Napoleon's invasion of Spain, the criollos of Santo Domingo revolted against the French regime. With the aid of Great Britain, the French was defeated, and Santo Domingo was returmed to Spanish control. France would never regain control of the island, and after some 12 years of Spanish dominion, the leaders in Santo Domingo revolted again, and eastern Hispaniola was declared independent as the Republic of Spanish Haiti in 1821. Fearing the influence of a society of slaves that had successfully revolted against their owners, the United States and European powers refused to recognize Haiti, the second republic in the Western Hemisphere. France demanded a high payment for compensation to slaveholders who lost their property, and Haiti was saddled with unmanageable debt for decades.[55] By this point, the entire island was united under Haitian control. However, suppression of the Dominican culture and the imposition of heavy taxation would lead to the Dominican War of Independence and the establishment of the Dominican Republic in 1844. (This is one of the reasons for the tensions between the two countries today). Years of war, political chaos and economic crisis came to an end with a reintegration of the Dominican Republic to Spanish rule in 1861, at the request of discouraged Dominican political leaders who had hoped that the Spanish would restore order to the country. However, just as in the España Boba period, taxations, corruption, and second class treatment of the Dominicans caused support for the regime to wane, and new independence movements had sparked throughout the country. In August 1863, the Dominican Restoration War erupted on the island, and after suffering heavy defeats, the Spanish Crown capitulated. A royal decree, The Treaty of El Carmelo, recognized the independence of the Dominican Republic, and the Spanish were expelled for good in 1865. Renewed annexation projects, this time to the United States, was defeated in Congress, and the masterminds were ousted in an uprising in 1874. Both states have remained independent states since then. 20th century to represent: Foreign intervention, dictatorships, aftermathIn the 20th century, however, both states have endured similar outcomes. With many ensuing conflicts such as Banana Wars and World War I taking place, political and economic instabilities continued to ravage as constant power struggles and civil wars engulfed among leaders in both states. Such actions triggered renewed external interest in launching military interventions on the island. This would finally come with U.S. forces issuing a military occupation of both states, first with Haiti in 1915, and the Dominican Republic in 1916. In the following decades after American forces departed from the island, both states would be ruled by heavy handed politicians that had risen to prominence during the American occupation. Haiti's François Duvalier (Papa Doc) and his son, Jean-Claude Duvalier (Baby Doc) and Dominican Republic's Rafael Trujillo would emerge as the leading autocratic rulers at this time. Eventually, the dictatorships of both countries came to a close with the assassination of Trujillo in 1961, (though political chaos ensued triggering a bloody revolution and a second U.S intervention in 1965), and the death of François Duvalier and overthrow of Jean-Claude Duvalier in 1971 and 1986, respectively. Both states would return to a democratic government, as proven with the elections of Jean-Bertrand Aristide in Haiti, and Joaquín Balaguer in the Dominican Republic. While the Dominican Republic was able to stabilize the political crisis that plagued the country since its conception since 1844, Haiti's political crisis continued to destabilize. The political chaos that erupted following the overthrow of Aristide in 2004 caused a mass intervention by the U.N., which lasted until 2017. Even by that point, Haiti had already suffered a massive catastrophic earthquake in 2010, cholera outbreaks continued, and gang violence had escalated further, which is still ongoing to this day. Haiti would become one of the poorest countries in the Americas, while the Dominican Republic [55] gradually has developed into one of the largest economies of Central America and the Caribbean. Geography Hispaniola is the second-largest island in the Caribbean (after Cuba), with an area of 76,192 square kilometers (29,418 sq mi), 48,440 square kilometers (18,700 sq mi)[56] of which is under the sovereignty of the Dominican Republic occupying the eastern portion and 27,750 square kilometers (10,710 sq mi)[13] under the sovereignty of Haiti occupying the western portion. The island of Cuba lies 80 kilometers (50 mi) to the west across the Windward Passage; to the southwest lie Jamaica, separated by the Jamaica Channel, the Cayman Islands and Navassa Island; 190 km (120 mi) . Puerto Rico lies 130 km (81 mi) east of Hispaniola across the Mona Passage. The Bahamas and Turks and Caicos Islands lie to the north. Its westernmost point is known as Cap Carcasse. Cuba, Cayman Islands, Navassa Island, Hispaniola, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico are collectively known as the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is also a part of the Antilles and the West Indies. The island has five major ranges of mountains: The Central Range, known in the Dominican Republic as the Cordillera Central, spans the central part of the island, extending from the south coast of the Dominican Republic into northwestern Haiti, where it is known as the Massif du Nord. This mountain range boasts the highest peak in the Antilles, Pico Duarte at 3,101 meters (10,174 ft) above sea level.[57] The Cordillera Septentrional runs parallel to the Central Range across the northern end of the Dominican Republic, extending into the Atlantic Ocean as the Samaná Peninsula. The Cordillera Central and Cordillera Septentrional are separated by the lowlands of the Cibao Valley and the Atlantic coastal plains, which extend westward into Haiti as the Plaine du Nord (Northern Plain). The lowest of the ranges is the Cordillera Oriental, in the eastern part of the country.[58] The Sierra de Neiba rises in the southwest of the Dominican Republic, and continues northwest into Haiti, parallel to the Cordillera Central, as the Montagnes Noires, Chaîne des Matheux and the Montagnes du Trou d'Eau. The Plateau Central lies between the Massif du Nord and the Montagnes Noires, and the Plaine de l'Artibonite lies between the Montagnes Noires and the Chaîne des Matheux, opening westward toward the Gulf of Gonâve, the largest gulf of the Antilles.[58] The southern range begins in the southwesternmost Dominican Republic as the Sierra de Bahoruco, and extends west into Haiti as the Massif de la Selle and the Massif de la Hotte, which form the mountainous spine of Haiti's southern peninsula. Pic de la Selle is the highest peak in the southern range, the third highest peak in the Antilles and consequently the highest point in Haiti, at 2,680 meters (8,790 ft) above sea level. A depression runs parallel to the southern range, between the southern range and the Chaîne des Matheux-Sierra de Neiba. It is known as the Plaine du Cul-de-Sac in Haiti, and Haiti's capital Port-au-Prince lies at its western end. The depression is home to a chain of salt lakes, including Lake Azuei in Haiti and Lake Enriquillo in the Dominican Republic.[58] The island has four distinct ecoregions. The Hispaniolan moist forests ecoregion covers approximately 50% of the island, especially the northern and eastern portions, predominantly in the lowlands but extending up to 2,100 meters (6,900 ft) elevation. The Hispaniolan dry forests ecoregion occupies approximately 20% of the island, lying in the rain shadow of the mountains in the southern and western portion of the island and in the Cibao valley in the center-north of the island. The Hispaniolan pine forests occupy the mountainous 15% of the island, above 850 metres (2,790 ft) elevation. The flooded grasslands and savannas ecoregion in the south central region of the island surrounds a chain of lakes and lagoons in which the most notable include that of Lake Azuei and Trou Caïman in Haiti and the nearby Lake Enriquillo in the Dominican Republic,[59] which is not only the lowest point of the island, but also the lowest point for an island country.[60]

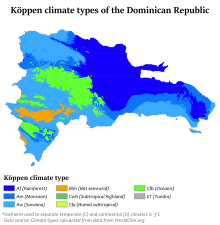

Climate    Hispaniola's climate shows considerable variation due to its diverse mountainous topography, and is the most varied island of all the Antilles.[61] Except in the Northern Hemisphere summer season, the predominant winds over Hispaniola are the northeast trade winds. As in Jamaica and Cuba, these winds deposit their moisture on the northern mountains, and create a distinct rain shadow on the southern coast, where some areas receive as little as 400 millimetres (16 in) of rainfall, and have semi-arid climates. Annual rainfall under 600 millimetres (24 in) also occurs on the southern coast of Haiti's northwest peninsula and in the central Azúa region of the Plaine du Cul-de-Sac. In these regions, moreover, there is generally little rainfall outside hurricane season from August to October, and droughts are by no means uncommon when hurricanes do not come.[62] On the northern coast, in contrast, rainfall may peak between December and February, though some rain falls in all months of the year. Annual amounts typically range from 1,700 to 2,000 millimetres (67 to 79 in) on the northern coastal lowlands;[61] there is probably much more in the Cordillera Septentrional, though no data exist. The interior of Hispaniola, along with the southeastern coast centered around Santo Domingo, typically receives around 1,400 millimetres (55 in) per year, with a distinct season from May to October. Usually, this wet season has two peaks: one around May, the other around the hurricane season. In the interior highlands, rainfall is much greater, around 3,100 millimetres (120 in) per year, but with a similar pattern to that observed in the central lowlands. The variations of temperature depend on altitude and are much less marked than rainfall variations in the island. Lowland Hispaniola is generally more hot and humid, with temperatures averaging 28 °C (82 °F). with high humidity during the daytime, and around 20 °C (68 °F) at night. At higher altitudes, temperatures fall steadily, so that frosts occur during the dry season on the highest peaks, where maxima are no higher than 18 °C (64 °F).

FaunaThere are many bird species in Hispaniola, and the island's amphibian species are also diverse. There are many species endemic to the island including insects and other invertebrates, reptiles, amphibians, fishs, birds and mammals (originally animals, native animals) and also (imported animals, introduced animals, not native animals or invasive species) just like farm animals, transport animals, house animals, pets and more. The two endemic terrestrial mammals on the island are the Hispaniolan hutia (Plagiodontia aedium) and the Hispaniolan solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus). There are also many avian species on the island, with six endemic genera (Calyptophilus, Dulus, Nesoctites, Phaenicophilus, Xenoligea and Microligea). More than half of the original distribution of its ecoregions has been lost due to habitat destruction impacting the local fauna and some of the original animals either threat, threatened with extinction or totally extinct, because of climate change or because they have been hunted by humans or their habitats have been felled or changed for some reasons or have become some of the animals have been threatened by (introduced animals, not native animals or invasive species) or there are fighting for space to survive and perhaps some animals that feed on the same plants or animals or just something like that.[63] Flora The island has four distinct ecoregions. The Hispaniolan moist forests ecoregion covers approximately 50% of the island, especially the northern and eastern portions, predominantly in the lowlands but extending up to 2,100 meters (6,900 ft) elevation. The Hispaniolan dry forests ecoregion occupies approximately 20% of the island, lying in the rain shadow of the mountains in the southern and western portion of the island, and in the Cibao valley in the center-north of the island. The Hispaniolan pine forests occupy the mountainous 15% of the island, above 850 metres (2,790 ft) elevation. The flooded grasslands and savannas ecoregion in the south central region of the island surrounds a chain of lakes and lagoons, the most notable of which are Etang Saumatre and Trou Caïman in Haiti and the nearby Lake Enriquillo in the Dominican Republic. In Haiti, deforestation has long been cited by scientists as a source of ecological crisis; the timber industry dates back to French colonial rule. Haiti has seen a dramatic reduction of forests due to the excessive and increasing use of charcoal as fuel for cooking. Various media outlets have suggested that the country has just 2% forest cover, but this has not been substantiated by research.[64] Also extremely important are the rarely mentioned species of Pinguicula casabitoana (a carnivorous plant), Gonocalyx tetraptera, Gesneria sylvicola, Lyonia alaini and Myrcia saliana, as well as palo de viento (Didymopanax tremulus), jaiqui (Bumelia salicifolia), pino criciolio) (pino criciol), sangre de pollo (Mecranium amigdalinum) and palo santo (Alpinia speciosa). According to reports in the Dominican Republic and Haiti, the flora in this naturally protected area consists of 621 species of vascular plants, of which 153 are highly endemic to La Hispaniola. The most prominent endemic species of flora that abound in the area are Ebano Verde (green ebony), Magnolia pallescens, a highly endangered hardwood. Recent in-depth studies of satellite imagery and environmental analysis regarding forest classification conclude that Haiti actually has approximately 30% tree cover;[65] this is, nevertheless, a stark decrease from the country's 60% forest cover in 1925. The country has been significantly deforested over the last 50 years, resulting in the desertification of many portions of Haitian territory. Haiti's poor citizens use cooking fires often, and this is a major culprit behind the nation's loss of trees. Haitians use trees as fuel either by burning the wood directly, or by first turning it into charcoal in ovens. Seventy-one percent of all fuel consumed in Haiti is wood or charcoal.[66] Haiti's government began establishing protected areas across the country in 1968. These 26 areas today represent nearly 7 per cent of the country's land and 1.5 per cent of its waters.[67] In the Dominican Republic, the forest cover has increased. In 2003, the Dominican Republic's forest cover had been reduced to 32% of its land area, but by 2011, forest cover had increased to nearly 40%. The success of the Dominican forest growth is due to several Dominican government policies and private organizations for the purpose of reforesting, and a strong educational campaign that has resulted in increased awareness by the Dominican people of the importance of forests for their welfare and other forms of life on the island.[68] Demographics  Hispaniola is the most populous Caribbean island with a combined population of 23 million inhabitants as of July 2023[update].[69] The Dominican Republic is a Hispanophone nation of approximately 11.3 million people. Spanish is spoken by essentially all Dominicans as a primary language. Roman Catholicism is the official and dominant religion and some Evangelicalism and Protestant churches and The Church of Jesus Christ and minority religions such as African religions, Afro-American religions, African diaspora religions, Haitian Vodou, Dominican Vodou, Dominican Santeria, Congos Del Espiritu Santo, Dominican Protestants, Pentecostals, Judaism, Islam and Baháʼí Faith, Hinduism, Buddhism, Unitarian Universalism, Jehovah's Witnesses, Pentecostalism and others also exist.   Haiti is a Creole-speaking nation of roughly 11.7 million people. Although French is spoken as a primary language by the educated and wealthy minority, virtually the entire population speaks Haitian Creole, one of several French-derived creole languages. Roman Catholicism is the dominant religion, practiced by more than half the population, although in some cases in combination with Haitian Vodou faith. Another 25% of the populace belong to Protestant churches.[70] Ethnic compositionThe ethnic composition of the Dominican population is 73% mixed ethnicity,[71] 16% white and 11% black. Descendants of early Spanish settlers and of black slaves from West Africa constitute the two main racial strains. The ethnic composition of Haiti is estimated to be 95% black and 5% white and Mulatto. In recent times, Dominican and Puerto Rican researchers identified in the current Dominican population the presence of genes belonging to the aborigines of the Canary Islands (commonly called Guanches).[72] These genes also have been detected in Puerto Rico.[73] Economics  The island has the largest economy in the Greater Antilles; however, most of the economic development is found in the Dominican Republic, the Dominican economy being nearly 800% larger than the Haitian economy. As of 2018[update], the estimated annual per capita income is US$868 in Haiti and US$8,050 in the Dominican Republic.[74][75] The divergence between the level of economic development in Haiti and the Dominican Republic makes its border the highest contrast of all western land borders.[76] Natural resourcesThe island also has an economic history and current day interest and involvement in precious metals. In 1860, it was observed that the island contained a large supply of gold, which the early Spaniards had hardly developed.[77] By 1919, Condit and Ross noted that much of the island was covered by government granted concessions for mining different types of minerals. Besides gold, these minerals included silver, manganese, copper, magnetite, iron and nickel.[78] Mining operations in 2016 have taken advantage of the volcanogenic massive sulfide ore deposits around Maimón. To the northeast, the Pueblo Viejo Gold Mine was operated by state-owned Rosario Dominicana from 1975 until 1991. In 2009, Pueblo Viejo Dominicana Corporation, formed by Barrick Gold and Goldcorp, started open-pit mining operations of the Monte Negro and Moore oxide deposits. The mined ore is processed with gold cyanidation. Pyrite and sphalerite are the main sulfide minerals found in the 120-meter thick volcanic conglomerates and agglomerates, which constitute the world's second largest sulphidation gold deposit.[79] Between Bonao and Maimón, Falconbridge Dominicana has been mining nickel laterites since 1971. The Cerro de Maimon copper/gold open-pit mine southeast of Maimón has been operated by Perilya since 2006. Copper is extracted from the sulfide ores, while gold and silver are extracted from both the sulfide and the oxide ores. Processing is via froth flotation and cyanidation. The ore is located in the VMS Early Cretaceous Maimón Formation. Goethite enriched with gold and silver is found in the 30-meter thick oxide cap. Below that cap is a supergene zone containing pyrite, chalcopyrite, and sphalerite. Below the supergene zone is found the unaltered massive sulphide mineralization.[80] Human developmentThis is a list of Dominican Republic and Haiti regions by Human Development Index as of 2018.[81]

See also

References

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||