|

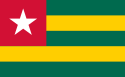

History of Togo

The history of Togo can be traced to archaeological finds which indicate that ancient local tribes were able to produce pottery and process tin. During the period from the 11th century to the 16th century, the Ewé, the Mina, the Gun, and various other tribes entered the region. Most of them settled in coastal areas. The Portuguese arrived in the late 15th century, followed by other European powers. Until the 19th century, the coastal region was a major slave trade centre, earning Togo and the surrounding region the name "The Slave Coast". In 1884, Germany claimed a coastal protectorate, which grew inland until it became the German colony of Togoland in 1905. A railway, the port of Lomé, and other infrastructure were developed. During the First World War, Togoland was invaded by Britain and France. In 1922, Great Britain received the League of Nations mandate to govern the western part of Togo and France to govern the eastern part. After World War II, these mandates became UN Trust Territories. The residents of British Togoland voted to join the Gold Coast as part of the new independent nation of Ghana in 1957. French Togoland became the Togolese Republic in 1960. Its Constitution, adopted in 1961, instituted the National Assembly of Togo as the supreme legislative body. In the same year, the first president, Sylvanus Olympio, dissolved the opposition parties and arrested their leaders. When he was assassinated in a coup in 1963, the military handed over power to an interim government led by Nicolas Grunitzky. The military leader Gnassingbé Eyadéma overthrew Grunitzky in a bloodless coup in 1967. He assumed the presidency and introduced a one-party system in 1969. Eyadéma remained in power for the next 38 years. When he died in 2005, the military installed his son, Faure Gnassingbé, as president. Gnassingbe held elections and won, but the opposition claimed fraud. Because of political violence, around 40,000 Togolese fled to neighboring countries. Gnassingbé was re-elected two more times. In late 2017, anti-government protests were suppressed by security forces. Pre-colonial

Little is known about the history of Togo before the late fifteenth century, when Portuguese explorers arrived, although there are signs of Ewe settlement for several centuries before their arrival.[1] Various tribes moved into the country from all sides – the Ewe from Benin, and the Mina and the Guin from Ghana. These three groups settled along the coast.[2] Before the colonial period, the various ethnic groups in Togo had little contact with each other. Except for two small kingdoms in the north, the territory consisted of groups of villages which were under military pressure from the two neighbouring West African powers – the Ashanti from Ghana and the Dahomey from Benin.[3] The first Europeans to see Togo were João de Santarém and Pêro Escobar, the Portuguese explorers who sailed along its coast between 1471 and 1473.[3] The Portuguese built forts in neighboring Ghana (at Elmina) and Benin (at Ouidah). Although the coast of Togo had no natural harbors, the Portuguese did trade at a small fort at Porto Seguro.[2] For the next 200 years, the coastal region was a major trading center for Europeans in search of slaves, earning Togo and the surrounding region the name "The Slave Coast". Colonial ruleGerman Togoland The German Empire established the protectorate of Togoland (in what is now the nation of Togo and most of what is now the Volta Region of Ghana) in 1884 during the period generally known as the "Scramble for Africa". Gustav Nachtigal, Germany's Commissioner for West Africa who oversaw both the inclusion of Togoland as well as Kamerun into the German colonial empire, had negotiated with King Mlapa III to gain control of the coast of what would eventually become Togoland, particularly the cities of Lomé, Sebe and Aného. France, at the time controller of neighboring Benin, recognized German rule in the region on 24 December 1885. The colony was established in part of what was then the Slave Coast and German control was gradually extended inland. Because it became Germany's only self-supporting colony and because of its extensive rail and road infrastructure—Germany had opened Togo's first rail line between Lomé and Aného in 1905—Togoland was known as its model possession.[4] At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 the colony was drawn into the conflict. It was invaded and quickly overrun by British and French forces during the Togoland campaign and placed under military rule. In 1916 the territory was divided into separate British and French administrative zones, and this was formalized in 1922 with the creation of British Togoland and French Togoland. League of Nations mandates On August 8, 1914, French and British forces invaded Togoland and the German forces there surrendered on 26 August. In 1916, Togoland was divided into French and British administrative zones. Following the war, Togoland formally became a League of Nations mandate divided for administrative purposes between France and the United Kingdom. After World War I, newly founded Czechoslovakia was also interested in this colony but this idea did not succeed. Lome was initially allocated to the British zone but after negotiations transferred to France 1 October 1920. After World War II, the mandate became a UN trust territory administered by the United Kingdom and France. During the mandate and trusteeship periods, western Togo was administered as part of the British Gold Coast. In December 1956, the residents of British Togoland voted to join the Gold Coast as part of the new independent nation of Ghana.  In the Representative Assembly elections in 1946, there were two parties, the Committee of Togolese Unity (CUT) and the Togolese Party of Progress (PTP). The CUT was overwhelmingly successful, and Sylvanus Olympio, the CUT leader became Council leader. However, the CUT was defeated in the 1951 Representative Assembly elections and the 1952 Territorial Assembly elections, and refused to participate in further French supervised elections because it claimed that the PTP was receiving French support.[5] By statute in 1955, French Togoland became an autonomous republic within the French union, although it retained its UN trusteeship status. Following elections to the Territorial Assembly on 12 June 1955, which were boycotted by CUT, considerable power over internal affairs was granted, with an elected executive body headed by a prime minister responsible to the legislature. These changes were embodied in a constitution approved in a 1956 referendum. On 10 September 1956, Nicolas Grunitzky became Prime Minister of the Republic of Togo. The situation escalated further on 21 June 1957, when the local population of the Pya-Hodo, Kozah, took advantage of the visit of the United Nations mission, to express its frustration with the French colonial administration. Faced with the anger of the demonstrators, protesting against the arrest of the Togolese nationalist, Bouyo Moukpé, the colonial army fired on the crowd that frequented the Hoda market, killing 20 and injuring many.[6] Due to irregularities in the plebiscite, a UN-supervised parliamentary election was held on 27 April 1958, the first held in Togo with universal suffrage, which was won by the opposition pro-independence CUT and its leader Sylvanus Olympio, who became prime minister. On 13 October 1958 the French government announced that full independence would be granted.[7] On 14 November 1958 the United Nations’ General Assembly took note of the French government's declaration according to which Togo which was under French administration would gain independence in 1960, thus marking an end to the trusteeship period.[8] On 5 December 1959 the United Nations’ General Assembly resolved that the UN Trusteeship Agreement with France for Cameroon would end when Togo became independent on 27 April 1960.[9] On 27 April 1960, in a smooth transition, Togo severed its constitutional ties with France, shed its UN trusteeship status, and became fully independent under a provisional constitution with Olympio as president. Independence and turmoil

A new constitution adopted by referendum in 1961 established an executive president, elected for 7 years by universal suffrage and a weak National Assembly. The president was empowered to appoint ministers and dissolve the assembly, holding a monopoly of executive power. In elections that year, from which Grunitzky's party was disqualified, Olympio's party won 100% of the vote and all 51 National Assembly seats, and he became Togo's first elected president. During this period, four principal political parties existed in Togo: the leftist Juvento, the Democratic Union of the Togolese People (UDPT), the PTP, founded by Grunitzky but having limited support, and the Party of Togolese Unity, the party of President Olympio. Rivalries between elements of these parties had begun as early as the 1940s, and they came to a head with Olympio dissolving the opposition parties in January 1962 because of alleged plots against the majority party government. The reign of Olympio was marked by the terror of his militia, the Ablode Sodjas. Many opposition members, including Grunitzky and Meatchi, were jailed or fled to avoid arrest. On 13 January 1963 Olympio was overthrown and killed in a coup d'état led by army non-commissioned officers dissatisfied with conditions following their discharge from the French army. Grunitzky returned from exile 2 days later to head a provisional government with the title of prime minister. On 5 May 1963, the Togolese adopted a new constitution by referendum, which reinstated a multi-party system. They also voted in a general election to choose deputies from all political parties for the National Assembly, and elected Grunitzky as president and Antoine Meatchi as vice president. Nine days later, President Grunitzky formed a government in which all parties were represented. During the next several years, the Grunitzky government's power became insecure. On 21 November 1966, an attempt to overthrow Grunitzky, inspired principally by civilian political opponents in the UT party, was unsuccessful. Grunitzky then tried to lessen his reliance on the army, but on 13 January 1967, a coup led by Lt. Col. Étienne Eyadéma (later Gen. Gnassingbé Eyadéma) and Kléber Dadjo ousted President Grunitzky without bloodshed. Following the coup, political parties were banned, and all constitutional processes were suspended. Dadjo became the chairman of the "committee of national reconciliation", which ruled the country until 14 April, when Eyadéma assumed the presidency. In late 1969, a single national political party, the Rally of the Togolese People (RPT), was created, and President Eyadéma was elected party president on 29 November 1969. In 1972, a referendum, in which Eyadéma ran unopposed, confirmed his role as the country's president. Eyadéma's rule

The third republicIn late 1979, Eyadéma declared a third republic and a transition to greater civilian rule with a mixed civilian and military cabinet. He garnered 99.97% of the vote in uncontested presidential elections held in late 1979 and early 1980. A new constitution also provided for a national assembly to serve primarily as a consultative body. Eyadéma was reelected to a third consecutive 7-year term in December 1986 with 99.5% of the vote in an uncontested election. On 23 September 1986, a group of some 70 armed Togolese dissidents crossed into Lomé from Ghana in an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the Eyadéma government. OppositionIn 1989 and 1990, Togo, like many other countries, was affected by the winds of democratic change sweeping Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. On 5 October 1990, the trial of students who handed out antigovernment tracts sparked riots in Lomé. Anti-government demonstrations and violent clashes with the security forces marked the months that followed. In April 1991, the government began negotiations with newly formed opposition groups and agreed to a general amnesty that permitted exiled political opponents to return to Togo. After a general strike and further demonstrations, the government and opposition signed an agreement to hold a "national forum" on 12 June 1991. The national forum, dominated by opponents of President Eyadéma, opened in July 1991 and immediately declared itself to be a sovereign "National Conference." Although subjected to severe harassment from the government, the conference drafted an interim constitution calling for a 1-year transitional regime tasked with organizing free elections for a new government. The conference selected Joseph Kokou Koffigoh, a lawyer and human rights group head, as transitional prime minister but kept President Eyadéma as chief of state for the transition, although with limited powers. A test of wills between the president and his opponents followed over the next 3 years during which President Eyadéma gradually gained the upper hand. Frequent political paralysis and intermittent violence marked this period. Following a vote by the transitional legislature (High Council of the Republic) to dissolve the President's political party—the RPT—in November 1991, the army attacked the prime minister's office on 3 December and captured the prime minister. Koffigoh then formed a second transition government in January 1992 with substantial participation by ministers from the President's party. Opposition leader Gilchrist Olympio, son of the slain president Sylvanus Olympio, was ambushed and seriously wounded apparently by soldiers on 5 May 1992. In July and August 1992, a commission composed of presidential and opposition representatives negotiated a new political agreement. On 27 September, the public overwhelmingly approved the text of a new, democratic constitution, formally initiating Togo's fourth republic. Powerless legislature and political violenceThe democratic process was set back in October 1991, when elements of the army held the interim legislature hostage for 24 hours. This effectively put an end to the interim legislature. In retaliation, on 16 November, opposition political parties and labor unions declared a general strike intended to force President Eyadéma to agree to satisfactory conditions for elections. The general strike largely shut down Lomé for months and resulted in severe damage to the economy. In January 1993, President Eyadéma declared the transition at an end and reappointed Koffigoh as prime minister under Eyadéma's authority. This set off public demonstrations, and, on 25 January, members of the security forces fired on peaceful demonstrators, killing at least 19. In the ensuing days, several security force members were waylaid and injured or killed by civilian oppositionists. On 30 January 1993, elements of the military went on an 8-hour rampage throughout Lomé, firing indiscriminately and killing at least 12 people. This incident provoked more than 300,000 Togolese to flee Lomé for Benin, Ghana, or the interior of Togo. Although most had returned by early 1996, some still remain abroad. On 25 March 1993, armed Togolese dissident commandos based in Ghana attacked Lomé's main military camp and tried unsuccessfully to kill President Eyadéma. They inflicted significant casualties, however, which set off lethal reprisals by the military against soldiers thought to be associated with the attackers. Negotiating with the oppositionUnder substantial domestic and foreign pressure and the burden of the general strike, the presidential faction entered negotiations with the opposition in early 1993. Four rounds of talks led to the 11 July Ouagadougou agreement setting forth conditions for upcoming presidential and legislative elections and ending the general strike as of 3 August 1993. The presidential elections were set for 25 August, but hasty and inadequate technical preparations, concerns about fraud, and the lack of effective campaign organization by the opposition led the chief opposition candidates—former minister and Organization of African Unity Secretary General Edem Kodjo and lawyer Yawovi Agboyibo—to drop out of the race before election day and to call for a boycott. President Eyadéma won the elections by a 96.42% vote against token opposition. About 36% of the voters went to the polls; the others boycotted. Ghana-based armed dissidents launched a new commando attack on military sites in Lomé in January 1994. President Eyadéma was unhurt, and the attack and subsequent reaction by the Togolese armed forces resulted in hundreds of deaths, mostly civilians. The government went ahead with legislative elections on 6 February and 20 February 1994. In generally free and fair polls as witnessed by international observers, the allied opposition parties UTD and CAR together won a narrow majority in the National Assembly. Edem Kodjo named as prime ministerOn April 22, President Eyadéma named Edem Kodjo, the head of the smaller opposition party, the UTD, as prime minister instead of Yawovi Agboyibo, whose CAR party had far more seats. Kodjo's acceptance of the post of prime minister provoked the CAR to break the opposition alliance and refuse to join the Kodjo government. Kodjo was then forced to form a governing coalition with the RPT. Kodjo's government emphasized economic recovery, building democratic institutions and the rule of law and the return of Togolese refugees abroad. In early 1995, the government made slow progress toward its goals, aided by the CAR's August 1995 decision to end a 9-month boycott of the National Assembly. However, Kodjo was forced to reshuffle his government in late 1995, strengthening the representation by Eyadéma's RPT party, and he resigned in August 1996. Since then, Eyadéma has reemerged with a sure grip on power, controlling most aspects of government. In the June 1998 presidential election, the government prevented citizens from effectively exercising the right to vote. The Interior Ministry declared Eyadéma the winner with 52% of the vote in the 1998 election; however, serious irregularities in the government's conduct of the election strongly favored the incumbent and appear to have affected the outcome materially. Although the government did not obstruct the functioning of political opponents openly, the President used the strength of the military and his government allies to intimidate and harass citizens and opposition groups. The government and the state remained highly centralized: President Eyadéma's national government appointed the officials and controlled the budgets of all subnational government entities, including prefectures and municipalities, and influenced the selection of traditional chiefs. National Assembly electionsThe second multi-party legislative elections of Eyadéma's 33-year rule were held on 21 March 1999. However, the opposition boycotted the election, in which the ruling party won 79 of the 81 seats in the National Assembly. Those two seats went to candidates from little-known independent parties. Procedural problems and significant fraud, particularly misrepresentation of voter turnout marred the legislative elections. After the legislative election, the government announced that it would continue to pursue dialog with the opposition. In June 1999, the RPT and opposition parties met in Paris, in the presence of facilitators representing France, Germany, the European Union, and La Francophonie (an international organization of French-speaking countries), to agree on security measures for formal negotiations in Lomé. In July 1999, the government and the opposition began discussions, and on 29 July 1999, all sides signed an accord called the "Lomé Framework Agreement", which included a pledge by President Eyadéma that he would respect the constitution and not seek another term as president after his current one expires in 2003. The accord also called for the negotiation of a legal status for opposition leaders, as well as for former heads of state (such as their immunity from prosecution for acts in office). In addition, the accord addressed the rights and duties of political parties and the media, the safe return of refugees, and the security of all citizens. The accord also contained a provision for compensating victims of political violence. The President also agreed to dissolve the National Assembly in March and hold new legislative elections, which would be supervised by an independent national election commission (CENI) and which would use the single-ballot method to protect against some of the abuses of past elections. However, the March 2000 date passed without presidential action, and new legislative elections were ultimately rescheduled for October 2001. Because of funding problems and disagreements between the government and opposition, the elections were again delayed, this time until March 2002. In May 2002 the government scrapped CENI, blaming the opposition for its inability to function. In its stead, the government appointed seven magistrates to oversee preparations for legislative elections. Not surprisingly, the opposition announced it would boycott them. Held in October, as a result of the opposition's boycott the government party won more than two-thirds of the seats in the National Assembly. In December 2002, Eyadéma's government used this rubber-stamp parliament to amend Togo's constitution, allowing President Eyadéma to run for an “unlimited” number of terms. A further amendment stated that candidates must reside in the country for at least 12 months before an election, a provision that barred the participation in the upcoming presidential election of popular Union des Forces du Progrès (UFC) candidate, Gilchrist Olympio, who had been in exile since 1992. The presidential election was held 1 June. President Eyadéma was re-elected with 57% of the votes, amid allegations of widespread vote rigging. Death of Eyadéma and Gnassingbé's rise President Eyadéma died on 5 February 2005 while on board an airplane en route to France for treatment for a heart attack. Papa Gnassingbé is said to have killed more than fifteen thousand people during his dictatorship. His son Faure Gnassingbé, the country's former minister of public works, mines, and telecommunications, was named president by Togo's military following the announcement of his father's death. Under international pressure from the African Union and the United Nations however, who both denounced the transfer of power from father to son as a coup, Gnassingbé was forced to step down on 25 February 2005, shortly after accepting the nomination to run for elections in April. Deputy Speaker Bonfoh Abbass was appointed interim president until the inauguration of the 24 April election winner. As to official results, the winner of the election was Gnassingbé who garnered 60% of the vote. Opposition leader Emmanuel Bob-Akitani however disputed the election and declared himself to be the winner with 70% of the vote. After the announcement of the results, tensions flared up and to date, 100 people have been killed. On 3 May 2005, Gnassingbé was sworn in and vowed to concentrate on "the promotion of development, the common good, peace and national unity". Faure Gnassingbé in power (2005–present)In August 2006 President Gnassingbe and members of the opposition signed the Global Political Agreement (GPA), bringing an end to the political crisis triggered by Gnassingbé Eyadéma's death in February 2005 and the flawed and violent electoral process that followed. The GPA provided for a transitional unity government whose primary purpose would be to prepare for benchmark legislative elections, originally scheduled for June 24, 2007. CAR opposition party leader and human rights lawyer Yawovi Agboyibo was appointed Prime Minister of the transitional government in September 2006. Leopold Gnininvi, president of the CDPA party, was appointed minister of state for mines and energy. The third opposition party, UFC, headed by Gilchrist Olympio, declined to join the government, but agreed to participate in the national electoral commission and the National Dialogue follow-up committee, chaired by Burkina Faso President Blaise Compaore. Parliamentary elections took place on October 14, 2007. Olympio, who returned from exile to campaign, took part for the first time in 17 years. The ruling party, Rally of the Togolese People (RPT), won a majority of the parliamentary seats in the election. International observers declared the poll "largely" free and fair. Despite these assurances, the secretary-general of the opposition party Union of Forces for Change(UFC) initially stated that his party would not accept the election results.[10] Mr Olympio stated that the election results did not properly represent the voters' will, pointing out that the UFC received nearly as many votes as the RPT, but that due to the way the electoral system was designed the UFC won far fewer seats.[11] In April 2015, President Faure Gnassingbe was re-elected for a third term.[12] In late 2017, tens of thousands of demonstrators gathered in a series of mass protests to demand the immediate resignation of President Faure Gnassingbe.[13] In February 2020, Faure Gnassingbé was again re-elected for his fourth presidential term. The opposition had a lot of accusations of fraud and irregularities.[14] The Gnassingbé family has ruled Togo since 1967, meaning it is Africa’s longest lasting dynasty.[15] In June 2022, Togo joined the Commonwealth of Nations as its 56th member.[16] See also

References

BibliographyFurther reading

External links |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||