|

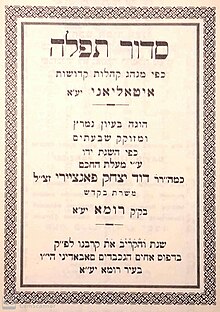

Italian Nusach The Italian Nusach[a][b] is the ancient prayer rite (nusach) of the long-standing Italian Jewish (Italkim) community on the Italian Peninsula, used by Jews who are not of Ashkenazi or Sephardic origin. HistoryThe Italian nusach has been considered an offspring of the ancient Land of Israel minhag and it has similarities with the nusach of the Romaniote Jews of Greece and the Balkans. However, the documents discovered in Cairo Geniza reveal that the influence of Minhag Eretz Israel on Benè Romì is less extensive than believed.[1] Communities where the Italian rite is practicedItalian Jews have their own unique prayer rite that is neither Sephardic nusach, Nusach Ashkenaz, nor Nusach Sefard, and to a certain extent is not subject to Kabbalistic influence. In Italy, there were also communities of Spanish origin who prayed in the Sephardic rite and communities of German origin who prayed in the Western Ashkenazic rite, which were mainly in northern Italy. The Italian rite, therefore, is not the rite of all Jews in Italy, but the rite of the veteran Italian Jews, called "Loazim". Despite being a dominant prayer rite among Italian Jews, the Italian rite rarely spread beyond its borders, unlike other prayer rites such as the Sephardic rite, which Spanish exiles brought to many places, or the Ashkenazic rite, which also reached new regions starting from the 19th century. The Italian rite hardly left the borders of Italy, except for a few cases where it reached other communities in the Middle East. For example, in the cities of Constantinople and Thessaloniki, several Italian synagogues operated until World War II, as well as in the city of Safed in the 16th and 17th centuries.[2] Today, communities using the Italian rite are active in Jerusalem and Netanya, the main one being in the main Italian synagogue on Hillel Steet in downtown Jerusalem. These synagogues in Jerusalem and Netanya are the only Italian rite synagogues in the world outside of Italy. Due to waves of immigration of Jews from Libya to Italy, after the establishment of the State of Israel until the end of the 1960s, the Sephardic rite became the dominant rite in southern and central Italy. Unique features of the Nusach

See alsoExternal links

NotesReferences

External links

|