|

Jermyn Street

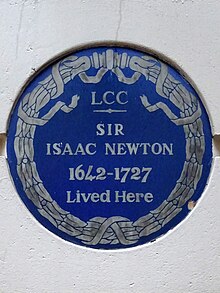

Jermyn Street is a one-way street in the St James's area of the City of Westminster in London, England. It is to the south of, parallel, and adjacent to Piccadilly. Jermyn Street is known as a street for gentlemen's-clothing retailers in the West End. History    In around 1664, the street was created by and named after Henry Jermyn, 1st Earl of St Albans, as part of his development of the St James's area of central London.[1] It was first recorded as "Jarman Streete" in the 1667 rate books of St Martin's, which listed 56 properties on it. In 1675, there were 108 names listed.[2] Notable residentsMany tailors owned or still own the houses along the street and often let rooms to people. No. 22, Jermyn Street, for instance was once owned by Italian silk merchant Cesare Salvucci and a military tailor who rented rooms out to people such as the banker Theodore Rothschild. The Duke of Marlborough lived there when he was Colonel Churchill, as did Isaac Newton (at No. 88, from 1696 to 1700; he then moved next door to No. 87, from 1700 to 1709, during which time he worked as Warden of the Mint), the mid-18th century highwayman and apothecary William Plunkett, the Duchess of Richmond, the Countess of Northumberland and the artist John Keyse Sherwin (in whose rooms in 1782 the actress Sarah Siddons sat for him for her portrait as Euphrasia).[3] The Gun Tavern[4] was one of the great resorts for foreigners of revolutionary tastes during the end of the 18th century, whilst Grenier's Hotel was patronised by French refugees. At the Brunswick Hotel, Louis Napoleon took up his residence under the assumed name of Count D'Arenberg on his escape from captivity in the fortress of Ham. Though he did not live there, a statue of the dandy Beau Brummell stands on Jermyn Street at its junction with Piccadilly Arcade, as embodying its elegant clothing values. Aleister Crowley lived in No. 93 during the Second World War up until 1 April.[5] It was through Crowley that Nancy Cunard resided in a flat in Jermyn Street.[6] New Zealand chefs and entertainers, Hudson and Halls, lived in a flat at No. 60 in the 1990s.[7] BusinessesJermyn Street shops traditionally sell shirts and other gentlemen's apparel, such as hats, shoes, shaving brushes, colognes, braces and collar stiffeners. The street is famous for its resident shirtmakers such as Turnbull & Asser, Hawes & Curtis, Thomas Pink, Hilditch & Key,[8] Harvie & Hudson, Emma Willis, and Charles Tyrwhitt. Gentlemen's outfitters Hackett is located on Jermyn Street, as well as shoe- and boot-makers John Lobb. A number of other related businesses occupy premises on the street, such as Sartoria dei Duchi - Atri, the men's luxury goods brand Alfred Dunhill, who opened its shop on the corner of Jermyn Street and Duke Street in 1907; barbers Geo.F. Trumper, and Taylor of Old Bond Street; and cigar shop Davidoff of London. The street also contains Britain's oldest cheese shop, Paxton & Whitfield, trading since 1797. Floris, a perfumers in the street, has display cabinets acquired directly from the Great Exhibition in 1851.[9] Forming part of the St James's Art District, there are a number of art galleries in Jermyn Street, including The Sladmore Gallery. Shops in this district are required to display art as part of their lease. Among the restaurants in the street are the historic Wiltons, the long established Rowley's Restaurant, the new Fortnum and Mason restaurant, and Franco's. Tramp nightclub and the 70-seat Jermyn Street Theatre (the West End's smallest)[10] are also on the street. Many of the buildings on Jermyn Street are owned by the Crown Estate. Listed buildings

Most of the buildings appear in Survey of London in The Parish of St James Westminster Part 1 South of Piccadilly: Volumes 29 and 30, Vol. 29 (1960), which can be viewed online.[25] Nikolaus Pevsner writes in The Buildings of England that "The Mid Victorian shop-front of No 97 is one of the best of its date in the West End". He calls no 93, which houses cheesemakers Paxton & Whitfield, "another good one".[26] See also

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Jermyn Street. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||