|

Jimmy Page

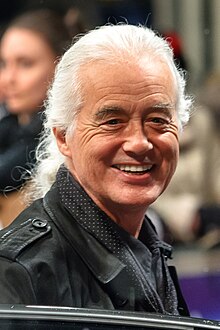

James Patrick Page OBE (born 9 January 1944) is an English musician and producer who achieved international success as the guitarist and founder of the rock band Led Zeppelin. Prolific in creating guitar riffs, Page's style involves various alternative guitar tunings and melodic solos, coupled with aggressive, distorted guitar tones. It is also characterized by his folk and eastern-influenced acoustic work. He is notable for occasionally playing his guitar with a cello bow to create a droning sound texture to the music.[1][2][3] Page began his career as a studio session musician in London and, by the mid-1960s, alongside Big Jim Sullivan, was one of the most sought-after session guitarists in Britain. He was a member of the Yardbirds from 1966 to 1968. When the Yardbirds broke up, he founded Led Zeppelin, which was active from 1968 to 1980. Following the death of Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham, he participated in a number of musical groups throughout the 1980s and 1990s, more specifically XYZ, the Firm, the Honeydrippers, Coverdale–Page, and Page and Plant. Since 2000, Page has participated in various guest performances with many artists, both live and in studio recordings, and participated in a one-off Led Zeppelin reunion in 2007 that was released as the 2012 concert film Celebration Day. Along with the Edge and Jack White, he participated in the 2008 documentary It Might Get Loud. Page is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential guitarists of all time.[4][5][6] Rolling Stone magazine has described Page as "the pontiff of power riffing" and ranked him number three in their 2015 list of the "100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time", behind Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton, and ranking 3rd again in 2023 behind Chuck Berry and Jimi Hendrix.[7][8][9] In 2010, he was ranked number two in Gibson's list of "Top 50 Guitarists of All Time" and, in 2007, number four on Classic Rock's "100 Wildest Guitar Heroes". He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame twice: once as a member of the Yardbirds (1992) and once as a member of Led Zeppelin (1995). Early lifePage was born to James Patrick Page and Patricia Elizabeth Gaffikin in the west London suburb of Heston on 9 January 1944.[10] His father was a personnel manager at a plastic-coatings plant[10] and his mother, who was of Irish descent,[11] was a doctor's secretary. In 1952, they moved to Feltham, and then to Miles Road, Epsom, in Surrey.[10] Page was educated from the age of eight at Epsom County Pound Lane Primary School, and when he was eleven he went to Ewell County Secondary School in West Ewell.[12] He came across his first guitar, a Spanish guitar,[12] in the Miles Road house: "I don't know whether [the guitar] was left behind by the people [in the house] before [us], or whether it was a friend of the family's—nobody seemed to know why it was there."[13] First playing the instrument when aged 12,[14] he took a few lessons in nearby Kingston, but was largely self-taught:

This "other guitarist" was a boy called Rod Wyatt, a few years his senior, and together with another boy, Pete Calvert, they would practise at Page's house; Page would devote six or seven hours on some days to practising and would always take his guitar with him to secondary school,[16] only to have it confiscated and returned to him after class.[17] Among Page's early influences were rockabilly guitarists Scotty Moore and James Burton, who both played on recordings made by Elvis Presley.[18] Presley's song "Baby Let's Play House" is cited by Page as being his inspiration to take up the guitar,[19] and he would reprise Moore's playing on the song in the live version of "Whole Lotta Love" on The Song Remains the Same.[20] He appeared on BBC1 in 1957 with a Höfner President acoustic, which he'd bought from money saved up from his milk round in the summer holidays and which had a pickup so it could be amplified,[21] but his first solid-bodied electric guitar was a second-hand 1959 Futurama Grazioso, later replaced by a Fender Telecaster,[22] a model he had seen Buddy Holly playing on the TV and a real-life example of which he'd played at an electronics exhibition at the Earls Court Exhibition Centre in London.[23] Page's musical tastes included skiffle (a popular English music genre of the time) and acoustic folk playing, and the blues sounds of Elmore James, B.B. King, Otis Rush, Buddy Guy, Freddie King, and Hubert Sumlin.[24] "Basically, that was the start: a mixture between rock and blues."[19] At the age of 13, Page appeared on Huw Wheldon's All Your Own talent quest programme in a skiffle quartet, one performance of which aired on BBC1 in 1957.[25] The group played "Mama Don't Want to Skiffle Anymore" and another American-flavoured song, "In Them Ol' Cottonfields Back Home".[26] When asked by Wheldon what he wanted to do after schooling, Page said, "I want to do biological research [to find a cure for] cancer, if it isn't discovered by then."[25] In an interview with Guitar Player magazine, Page stated that "there was a lot of busking in the early days, but as they say, I had to come to grips with it and it was a good schooling."[19] When he was fourteen, and billed as James Page, he played in a group called Malcolm Austin and Whirlwinds, alongside Tony Busson on bass, Stuart Cockett on rhythm and a drummer named Tom, playing Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis numbers. This band was short-lived, as Page soon found a drummer for a band he'd previously been playing in with Rod Wyatt, David Williams and Pete Calvert, and came up with a name for them: The Paramounts.[27] The Paramounts played gigs in Epsom, once supporting a group who would later become Johnny Kidd & the Pirates.[28] Although interviewed for a job as a laboratory assistant, he ultimately chose to leave secondary school in West Ewell to pursue music,[17] doing so at the age of fifteen – the earliest age permitted at the time – having gained four GCE O levels and on the back of a major row with the school Deputy Head Miss Nicholson about his musical ambitions, about which she was wholly scathing.[29] Page had difficulty finding other musicians with whom he could play on a regular basis. "It wasn't as though there was an abundance. I used to play in many groups ... anyone who could get a gig together, really."[22] Following stints backing recitals by Beat poet Royston Ellis at the Mermaid Theatre between 1960 and 1961,[1] and singer Red E. Lewis, who'd seen him playing with the Paramounts at the Contemporary club in Epsom and told his manager Chris Tidmarsh to ask Page to join his backing band, the Redcaps, after the departure of guitarist Bobby Oats,[30] Page was asked by singer Neil Christian to join his band, the Crusaders. Christian had seen a fifteen-year-old Page playing in a local hall,[22] and the guitarist toured with Christian for approximately two years and later played on several of his records, including the 1962 single, "The Road to Love".[31] During his stint with Christian, Page fell seriously ill with glandular fever and could not continue touring.[22] While recovering, he decided to put his musical career on hold and concentrate on his other love, painting, and enrolled at Sutton Art College in Surrey.[6] As he explained in 1975:

CareerEarly 1960s: session musicianWhile still a student, Page often performed on stage at the Marquee Club with bands such as Cyril Davies' All Stars, Alexis Korner's Blues Incorporated, and fellow guitarists Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton. He was spotted one night by John Gibb of Brian Howard & the Silhouettes, who asked him to help record some singles for Columbia Graphophone Company, including "The Worrying Kind". Mike Leander of Decca Records first offered Page regular studio work. His first session for the label was the recording "Diamonds" by Jet Harris and Tony Meehan, which went to Number 1 on the singles chart in early 1963.[22] After brief stints with Carter-Lewis and the Southerners, Mike Hurst and the Method and Mickey Finn and the Blue Men, Page committed himself to full-time session work. As a session guitarist, he was known as 'Lil' Jim Pea' to prevent confusion with the other noted English session guitarist Big Jim Sullivan. Page was mainly called into sessions as "insurance" in instances when a replacement or second guitarist was required by the recording artist. "It was usually myself and a drummer", he explained, "though they never mention the drummer these days, just me ... Anyone needing a guitarist either went to Big Jim [Sullivan] or myself."[22] He stated that "In the initial stages they just said, play what you want, cos at that time I couldn't read music or anything."[32] Page was the favoured session guitarist of record producer Shel Talmy. As a result, he secured session work on songs for the Who and the Kinks.[34] Page is credited with playing acoustic twelve-string guitar on two tracks on the Kinks' debut album, "I'm a Lover Not a Fighter" and "I've Been Driving on Bald Mountain",[35] and possibly on the B-side "I Gotta Move".[36] He played rhythm guitar on the sessions for the Who's first single "I Can't Explain"[32] (although Pete Townshend was reluctant to allow Page's contribution on the final recording; Page also played lead guitar on the B-side, "Bald Headed Woman").[37] Page's studio gigs in 1964 and 1965 included Marianne Faithfull's "As Tears Go By", Jonathan King's "Everyone's Gone to the Moon", the Nashville Teens' "Tobacco Road", the Rolling Stones "Heart of Stone" (along with "We're Wasting Time") (also, Van Morrison & Them's "Baby, Please Don't Go", "Mystic Eyes", and "Here Comes the Night", Dave Berry's "The Crying Game" and "My Baby Left Me", Brenda Lee's "Is It True", Shirley Bassey's "Goldfinger",[38] and Petula Clark's "Downtown". In 1964, Page contributed guitar to the incidental music of the Beatles' 1964 film A Hard Day's Night.[39] In 1965, Page was hired by Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham to act as house producer and A&R man for the newly formed Immediate Records label, which allowed him to play on and/or produce tracks by John Mayall, Nico, Chris Farlowe, Twice as Much and Clapton. Also in 1965, Page produced one of Dana Gillespie's early singles, "Thank You Boy".[40] Page also formed a brief songwriting partnership with then romantic interest Jackie DeShannon. He composed and recorded songs for the John Williams (not to be confused with the film composer John Williams) album The Maureeny Wishful Album with Big Jim Sullivan. Page worked as session musician on Donovan Leitch's Sunshine Superman, on Engelbert Humperdinck's Release Me,[41] the Johnny Hallyday albums Jeune homme and Je suis né dans la rue, the Al Stewart album Love Chronicles and played guitar on five tracks of Joe Cocker's debut album, With a Little Help from My Friends. Over the years since 1970, Page played lead guitar on 10 Roy Harper tracks, comprising 81 minutes of music. When questioned about which songs he played on, especially ones where there exists some controversy as to what his exact role was, Page often points out that it is hard to remember exactly what he did given the enormous number of sessions he was playing at the time.[32][34] In a radio interview, he explained that "I was doing three sessions a day, fifteen sessions a week. Sometimes I would be playing with a group, sometimes I could be doing film music, it could be a folk session ... I was able to fit all these different roles."[15] Although Page recorded with many notable musicians, many of these early tracks are only available as bootleg recordings, several of which were released by the Led Zeppelin fan club in the late 1970s. Examples include early jam sessions featuring him and guitarists Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton covering various blues themes, which were included on compilations released by Immediate Records. Several early tracks were compiled on the twin album release, Jimmy Page: Session Man. He also recorded with Keith Richards on guitar and vocals in Olympic Sound Studios on 15 October 1974. Along with Ric Grech on bass and Bruce Rowland on drums, a track called "Scarlet" was cut (the same year he played acoustic guitar on The Stones' "Through the Lonely Nights"). Page reflected later in an interview with Rolling Stone's Cameron Crowe: "I did what could possibly be the next Stones B side. It was Ric Grech, Keith and me doing a number called "Scarlet". I can't remember the drummer. It sounded very similar in style and mood to those Blonde on Blonde tracks. It was great, really good. We stayed up all night and went down to Island Studios where Keith put some reggae guitars over one section. I just put some solos on it, but it was eight in the morning of the next day before I did that. He took the tapes to Switzerland and someone found out about them. Richards told people that it was a track from my album".[14] Page left studio work when the increasing influence of Stax Records on popular music led to the greater incorporation of brass and orchestral arrangements into recordings at the expense of guitars.[19] He stated that his time as a session player served as extremely good schooling:

Late 1960s: The YardbirdsIn late 1964, Page was approached about the possibility of replacing Eric Clapton in the Yardbirds, but he declined out of loyalty to his friend. In February 1965, Clapton quit the Yardbirds and Page was formally offered his spot, but unwilling to give up his lucrative career as a session musician and worried about his health under touring conditions, he suggested his friend Jeff Beck.[42] On 16 May 1966, drummer Keith Moon, bass player John Paul Jones, keyboardist Nicky Hopkins, Jeff Beck and Page recorded "Beck's Bolero" in London's IBC Studios. The experience gave Page an idea to form a new supergroup featuring Beck, along with The Who's John Entwistle on bass and Moon on drums.[22] However, the lack of a quality vocalist and contractual problems prevented the project from getting off the ground. During this time, Moon suggested the name "Lead Zeppelin" for the first time, after Entwistle commented that the proceedings would take to the air like a lead balloon. Within weeks, Page attended a Yardbirds concert at Oxford. After the show, he went backstage where Paul Samwell-Smith announced that he was leaving the group.[19] Page offered to replace Samwell-Smith, and this was accepted by the group. He initially played electric bass with the Yardbirds before finally switching to twin lead guitar with Beck when Chris Dreja moved to bass. The musical potential of the line-up was scuttled, however, by interpersonal conflicts caused by constant touring and a lack of commercial success, although they released one single, "Happenings Ten Years Time Ago". While Page and Beck played together in the Yardbirds, the trio of Page, Beck and Clapton never played in the original group at the same time. The three guitarists did appear on stage together at the ARMS Charity Concerts in 1983. After Beck's departure, the Yardbirds remained a quartet. They recorded one album with Page on lead guitar, Little Games. The album received indifferent reviews and was not a commercial success, peaking at number 80 on the Billboard 200. Though their studio sound was fairly commercial at the time, the band's live performances were just the opposite, becoming heavier and more experimental. These concerts featured musical aspects that Page would later perfect with Led Zeppelin, most notably performances of "Dazed and Confused". After the departure of Keith Relf and Jim McCarty in 1968, Page reconfigured the group with a new line-up to fulfill unfinished tour dates in Scandinavia. To this end, Page recruited vocalist Robert Plant and drummer John Bonham, and he was also contacted by John Paul Jones, who asked to join.[43] During the Scandinavian tour, the new group appeared as the New Yardbirds, but soon recalled the old joke by Keith Moon and John Entwistle. Page stuck with that name to use for his new band. Manager Peter Grant changed it to "Led Zeppelin", to avoid a mispronunciation as "Leed Zeppelin".[44] 1968–1980: Led Zeppelin  Led Zeppelin are one of the best-selling music groups in the history of audio recording. Various sources estimate the group's worldwide sales at more than 200 or even 300 million albums. With 111.5 million RIAA-certified units, they are the second-best-selling band in the United States. Each of their nine studio albums reached the top 10 of the US Billboard album chart, and six reached the number-one spot.[citation needed] Led Zeppelin were the progenitors of heavy metal and hard rock, and their sound was largely the product of Page's input as a producer and musician.[citation needed] The band's individualistic style drew from a wide variety of influences. They performed on multiple record-breaking concert tours, which also earned them a reputation for excess. Although they remained commercially and critically successful, in the later 1970s, the band's output and touring schedule were limited by the personal difficulties of the members. Page explained that he had a very specific idea in mind as to what he wanted Led Zeppelin to be, from the very beginning:

Led Zeppelin broke up in 1980 following the death of Bonham at Page's home. Page initially refused to touch a guitar, grieving for his friend.[32][45] For the rest of the 1980s, his work consisted of a series of short-term collaborations in the bands the Firm, the Honeydrippers, reunions and individual work, including film soundtracks. He also became active in philanthropic work. 1980sPage made a return to the stage at a Jeff Beck show in March 1981 at the Hammersmith Odeon.[46] Also in 1981, Page joined with Yes bassist Chris Squire and drummer Alan White to form a supergroup called XYZ (for former Yes-Zeppelin). They rehearsed several times, but the project was shelved. Bootlegs of these sessions revealed that some of the material emerged on later projects, notably The Firm's "Fortune Hunter" and Yes songs "Mind Drive" and "Can You Imagine?". Page joined Yes on stage in 1984 at Westfalenhalle in Dortmund, Germany, playing "I'm Down". In 1982, Page collaborated with director Michael Winner to record the Death Wish II soundtrack. This and several subsequent Page recordings, including the Death Wish III soundtrack, were recorded and produced at his recording studio, The Sol in Cookham, which he had purchased from Gus Dudgeon in the early 1980s.  In 1983, Page appeared with the A.R.M.S. (Action Research for Multiple Sclerosis) charity series of concerts which honoured Small Faces bassist Ronnie Lane, who suffered from the disease. For the first shows at the Royal Albert Hall in London, Page's set consisted of songs from the Death Wish II soundtrack (with Steve Winwood on vocals) and an instrumental version of "Stairway to Heaven". A four-city tour of the United States followed, with Paul Rodgers of Bad Company replacing Winwood. During the tour, Page and Rodgers performed "Midnight Moonlight", which would later appear on The Firm's first album. All of the shows featured an on stage jam of "Layla" that reunited Page with Beck and Clapton. According to the book Hammer of the Gods, it was reportedly around this time that Page told friends that he had just ended seven years of heroin use. On 13 December 1983, Page joined Plant on stage for one encore at the Hammersmith Odeon in London. Page next linked up with Roy Harper for the 1984 album Whatever Happened to Jugula? and occasional concerts, performing a predominantly acoustic set at folk festivals under various guises such as the MacGregors and Themselves. Also in 1984, Page recorded with Plant as the Honeydrippers the album The Honeydrippers: Volume 1 and with John Paul Jones on the film soundtrack Scream for Help. Page subsequently collaborated with Rodgers on two albums under the name The Firm.[47] The first album, released in 1985, was the self-titled The Firm. Popular songs included "Radioactive" and "Satisfaction Guaranteed". The album peaked at number 17 on the Billboard pop albums chart and went gold in the US. It was followed by Mean Business in 1986. The band toured in support of both albums, but soon split up. Various other projects followed, such as session work for Graham Nash, Stephen Stills and the Rolling Stones (on their 1986 single "One Hit (To the Body)"). In 1986, Page reunited temporarily with his former Yardbirds bandmates to play on several tracks of the Box of Frogs album Strange Land.[48] Page released a solo album entitled Outrider in 1988, which featured contributions from Plant, with Page contributing in turn to Plant's solo album Now and Zen, which was released the same year. Outrider also featured singer John Miles on the album's opening track "Wasting My Time".[citation needed] Throughout these years, Page also reunited with the other former bandmates of Led Zeppelin to perform live on a few occasions, most notably in 1985 for the Live Aid concert with both Phil Collins and Tony Thompson filling drum duties. However, the band members considered this performance to be sub-standard, with Page having been let down by a poorly tuned Les Paul. Page, Plant and Jones, as well as John Bonham's son Jason, performed at the Atlantic Records 40th Anniversary show on 14 May 1988, closing the 12-hour show.[49] 1990s: Coverdale–Page, Page and PlantIn 1990, a Knebworth concert to aid the Nordoff-Robbins Music Therapy Centre and the British School for Performing Arts and Technology saw Plant unexpectedly joined by Page to perform "Misty Mountain Hop", "Wearing and Tearing" and "Rock and Roll". The same year, Page appeared with Aerosmith at the Monsters of Rock festival. Page also performed with the band's former members at Jason Bonham's wedding.[citation needed] In 1993, Page collaborated with David Coverdale (of English rock band Whitesnake) for the album Coverdale–Page and a brief tour of Japan. In 1994, Page and Robert Plant reunited as Page and Plant for an initial performance as part of MTV's "Unplugged" series. The 90-minute special, dubbed Unledded, premiered to the highest ratings in MTV's history. In October of the same year, the session was released as the live album No Quarter: Jimmy Page and Robert Plant Unledded, and on DVD as No Quarter Unledded in 2004. Following a highly successful mid-1990s tour to support No Quarter, Page and Plant recorded 1998's Walking into Clarksdale, featuring the Grammy Award-winning songs "Most High" and "Please Read the Letter".[50] Page was heavily involved in remastering the Led Zeppelin catalogue. He participated in various charity concerts and charity work, particularly the Action for Brazil's Children Trust (ABC Trust), founded by his wife Jimena Gomez-Paratcha in 1998. In the same year, Page played guitar for rap singer/producer Puff Daddy's song "Come with Me", which heavily samples Led Zeppelin's "Kashmir" and was included in the soundtrack of Godzilla. The two later performed the song on Saturday Night Live.[51] Following a benefit performance in the summer where the Black Crowes guested with him, Page teamed up with the band for six shows in October 1999, playing material from the Led Zeppelin catalogue and old blues and rock standards.[52][53] The last two concerts were recorded in Los Angeles and released as a double live album, Live at the Greek in 2000. 2000sFollowing the release of the live album, Page and the Black Crowes continued their collaboration by joining a package tour with the Who in 2000, which Page ultimately quit before completion.[54] In 2001, after guesting with Fred Durst and Wes Scantlin's performance of "Thank You" at the MTV Europe Video Music Awards, Page once again continued his collaboration with Robert Plant.[55] After recording a cover of "My Bucket's Got a Hole in It" for a tribute album, the duo performed at the Montreux Jazz Festival.[56] In 2005, Page was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in recognition of his Brazilian charity work for Task Brazil and Action For Brazil's Children's Trust,[57] made an honorary citizen of Rio de Janeiro later that year[58] and won a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award with Led Zeppelin.[59] In November 2006, Led Zeppelin was inducted into the UK Music Hall of Fame. The television broadcasting of the event consisted of an introduction to the band by various famous admirers (including Roger Taylor, Slash, Joe Perry, Steven Tyler, Jack White and Tony Iommi), an award presentation to Page and a short speech by him. After this, rock group Wolfmother played a tribute to Led Zeppelin.[60] During an interview for the BBC in connection with the induction, Page expressed plans to record new material in 2007, saying: "It's an album that I really need to get out of my system ... there's a good album in there and it's ready to come out" and "Also there will be some Zeppelin things on the horizon."[61]  On 10 December 2007, the surviving members of Led Zeppelin, as well as John Bonham's son, Jason Bonham played a charity concert at the O2 Arena London. According to Guinness World Records 2009, Led Zeppelin set the world record for the "Highest Demand for Tickets for One Music Concert" as 20 million requests for the reunion show were rendered online.[62] On 7 June 2008, Page and John Paul Jones appeared with the Foo Fighters to close the band's concert at Wembley Stadium, performing "Rock and Roll" and "Ramble On".[63] On 20 June 2008, at a ceremony at Guildford Cathedral, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Surrey.[64][65] For the 2008 Summer Olympics, Page, David Beckham and Leona Lewis represented Britain during the closing ceremonies on 24 August 2008. Beckham rode a double-decker bus into the stadium, and Page and Lewis performed "Whole Lotta Love".[66]  In 2008, Page co-produced a documentary film directed by Davis Guggenheim entitled It Might Get Loud. The film examines the history of the electric guitar, focusing on the careers and styles of Page, The Edge and Jack White. The film premiered on 5 September 2008 at the Toronto International Film Festival.[67] Page also participated in the three-part BBC documentary London Calling: The making of the Olympic handover ceremony on 4 March 2009.[68] On 4 April 2009, Page inducted Jeff Beck into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[69] Page announced his 2010 solo tour while talking to Sky News on 16 December 2009.[70][71] 2010sIn January 2010, Page announced an autobiography published by Genesis Publications, in a hand-crafted, limited edition of 2,150 copies.[72] Page was honoured with a first-ever Global Peace Award by the United Nations' Pathways to Peace organisation after confirming reports that he would be among the headliners at a planned Show of Peace Concert in Beijing, on 10 October 2010.[73][74] On 3 June 2011, Page played with Donovan at the Royal Albert Hall in London. The concert was filmed. Page made an unannounced appearance with The Black Crowes at the Shepherd's Bush Empire in London on 13 July 2011. He also played alongside Roy Harper at Harper's 70th-birthday celebratory concert, in London's Royal Festival Hall on 5 November 2011.[75]  In November 2011, British Conservative MP Louise Mensch launched a campaign to have Page knighted for his contributions to the music industry.[76] In December 2012, Page, along with Plant and Jones, received the annual Kennedy Center Honors[77] from President Barack Obama in a White House ceremony. The honour is the U.S.'s highest award for those who have influenced American culture through the arts.[78] In February 2013, Plant hinted that he was open to a Led Zeppelin reunion in 2014, stating that he is not the reason for the band's dormancy, saying "Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones are quite contained in their own worlds and leave it to [him]", adding that he is "not the bad guy" and that he has "got nothing to do in 2014."[79] In 2013, Page (with Led Zeppelin) was awarded a Grammy Award "Best Rock Album" for Celebration Day.[50] In May 2014, Page was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Berklee College of Music in Boston.[80] In a spring 2014 interview with the BBC about the then forthcoming reissue of Led Zeppelin's first three albums, Page said he was confident fans would be keen on another reunion show, but Plant later replied that "the chances of it happening [were] zero." Page then told The New York Times that he was "fed up" with Plant's refusal to play, stating "I was told last year that Robert Plant said he is doing nothing in 2014, and what do the other two guys think? Well, he knows what the other guys think. Everyone would love to play more concerts for the band. He's just playing games, and I'm fed up with it, to be honest with you. I don't sing, so I can't do much about it", adding, "I definitely want to play live. Because, you know, I've still got a twinkle in my eye. I can still play. So, yeah, I'll just get myself into musical shape, just concentrating on the guitar."[81] In July 2014, an NME article revealed that Plant was "slightly disappointed and baffled" by Page in ongoing Led Zeppelin dispute during which Page declared he was "fed up" with Plant delaying Led Zeppelin reunion plans. Instead, Plant offered Led Zeppelin's guitarist to write acoustically with him as he is interested in working with Page again but only in an unplugged way.[82] In September 2014, Page – who has not toured as a solo act since 1988 – announced that he would start a new band and perform material spanning his entire career. He spoke about his prospects for hitting the road, saying: "I haven't put [musicians] together yet but I'm going to do that next year [i.e. 2015]. If I went out to play, I would play material that spanned everything from my recording career right back to my very, very early days with The Yardbirds. There would certainly be some new material in there as well ...".[83] In December 2015, Page was featured in the two-hour long BBC Radio 2 programme Johnny Walker Meets, in conversation with DJ Johnny Walker.[84] In October 2017, Page spoke at the Oxford Union about his career in music.[85] 2020sPage is among the people interviewed for the documentary film If These Walls Could Sing directed by Mary McCartney about the recording studios at Abbey Road.[86] Legacy

—Chipkin, Stang in 2003[87]

Page is considered – by musical peers – one of the greatest and most influential guitarists. His experiences in the studio and with the Yardbirds were key to the success of Led Zeppelin. As a producer, songwriter and guitarist, he helped make Zeppelin a prototype for countless bands and was one of the major driving forces behind the rock sound of that era, influencing a host of guitarists.[88][89] Guitarists influenced by Page include Eddie Van Halen,[90] Ace Frehley,[91] Joe Satriani,[92] John Frusciante,[93] Kirk Hammett,[94] Joe Perry,[95] Richie Sambora,[96] Slash,[97] Dave Mustaine,[98] Mick Mars,[99] Alex Lifeson,[100] Steve Vai,[101] Dan Hawkins,[102] and Char,[103] among others. John McGeoch was described as "the new wave Jimmy Page" by Mojo magazine.[104] Queen's Brian May told Guitarist in 2004: "I don't think anyone has epitomised riff writing better than Jimmy Page—he's one of the great brains of rock music."[105] "If Jimmy Page would play guitar with me," remarked Stevie Nicks, "I'd put a band around us tomorrow."[106] Equipment and techniquesGuitars For the recording of most of Led Zeppelin material from Led Zeppelin's second album onwards, Page used a Gibson Les Paul guitar (sold to him by Joe Walsh) with Marshall amplification. A Harmony Sovereign H-1260 was used in-studio on Led Zeppelin III and Led Zeppelin IV and on-stage from 5 March 1971 to 28 June 1972. During the studio sessions for Led Zeppelin and later for recording the guitar solo in "Stairway to Heaven", he used a Fender Telecaster (a gift from Jeff Beck).[107] He also used a Danelectro 3021, tuned to DADGAD, most notably on live performances of "Kashmir". Page also plays his guitar with a cello bow,[1][2][3] as on the live versions of the songs "Dazed and Confused" and "How Many More Times". This was a technique he developed during his session days.[34] On MTV's Led Zeppelin Rockumentary, Page said that he obtained the idea of playing the guitar with a bow from David McCallum, Sr. who was also a session musician. Page used his Fender Telecaster and later his Gibson Les Paul for his bow solos.[108] Notable guitars

Strings

Signature modelsGibson released a Jimmy Page Signature Les Paul, discontinued in 1999, then released another version in 2004, which was also discontinued. The 2004 version included 25 guitars signed by Page, 150 aged by Tom Murphy (an acknowledged ageing "master") and 840 "unlimited" production guitars. The Jimmy Page Signature EDS-1275 has been produced by Gibson. Recently, Gibson reproduced Page's 1960 Les Paul Black Beauty, the one stolen from him in 1970, with modern modifications. This guitar was sold in 2008 with a run of 25, again signed by Page, plus an additional 500 unsigned guitars. In December 2009, Gibson released the 'Jimmy Page "Number Two" Les Paul'.[117] This is a re-creation of Page's famous "Number Two" Les Paul used by him since about 1974. The model includes the same pick-up switching setup as devised by Page, shaved-down neck profile, Burstbucker pick-up at neck and "Pagebucker" at the bridge. A total of 325 were made in three finishes: 25 Aged by Gibson's Tom Murphy, signed and played by Page ($26,000), 100 aged ($16,000) and 200 with VOS finish ($12,000). In 2019, Fender released two signature models, both based on Page's 1959 Telecaster (which he received as a gift from Jeff Beck):

Other instrumentsTheremin Page frequently employed a scaled-down version of the Theremin known as the Sonic Wave, first using the instrument during live performances with the Yardbirds. As a member of Led Zeppelin, Page played the Sonic Wave on the studio recordings of "Whole Lotta Love" and "No Quarter", and frequently played the instrument at the band's live shows.[119][120] Hurdy-gurdy Page owns two hurdy-gurdies, and is shown playing one of the instruments in the 1976 film The Song Remains the Same. The second hurdy-gurdy owned by Page was produced by Christopher Eaton, father of renowned English hurdy-gurdist Nigel Eaton.[119] Amplifiers and effectsPage usually recorded in studio with assorted amplifiers by Vox, Axis, Fender and Orange amplification. Live, he used Hiwatt and Marshall amplification. The first Led Zeppelin album was played on a Fender Telecaster through a Supro amplifier.[120] Page used a limited number of effects, including a Maestro Echoplex,[120][121][122] a Dunlop Cry Baby, an MXR Phase 90, a Vox Cry Baby Wah, a Boss CE-2 Chorus, a Yamaha CH-10Mk II Chorus, a Sola Sound Tone Bender Professional Mk II, an MXR Blue Box (distortion/octaver) and a DigiTech Whammy.[120] Music production techniquesPage is credited for the innovations in sound recording he brought to the studio during the years he was a member of Led Zeppelin,[123][124] many of which he had initially developed as a session musician:[125]

He developed a reputation for employing effects in new ways and trying out different methods of using microphones and amplification. During the late 1960s, most British music producers placed microphones directly in front of amplifiers and drums, resulting in the sometimes "tinny" sound of the recordings of the era. Page commented to Guitar World magazine that he felt the drum sounds of the day in particular "sounded like cardboard boxes."[123] Instead, Page was a fan of 1950s recording techniques, Sun Studio being a particular favourite. In the same Guitar World interview, Page remarked: "Recording used to be a science" and "[engineers] used to have a maxim: distance equals depth." Taking this maxim to heart, Page developed the idea of placing an additional microphone some distance from the amplifier (as much as twenty feet) and then recording the balance between the two. By adopting this technique, Page became one of the first British producers to record a band's "ambient sound" – the distance of a note's time-lag from one end of the room to the other.[126] For the recording of several Led Zeppelin tracks, such as "Whole Lotta Love" and "You Shook Me", Page additionally utilised "reverse echo" – a technique which he claims to have invented himself while with the Yardbirds (he had originally developed the method when recording the 1967 single "Ten Little Indians").[123] This production technique involved hearing the echo before the main sound instead of after it, achieved by turning the tape over and employing the echo on a spare track, then turning the tape back over again to get the echo preceding the signal. Page has stated that, as producer, he deliberately changed the audio engineers on Led Zeppelin albums, from Glyn Johns for the first album, to Eddie Kramer for Led Zeppelin II, to Andy Johns for Led Zeppelin III and later albums. He explained: "I consciously kept changing engineers because I didn't want people to think that they were responsible for our sound. I wanted people to know it was me."[123] John Paul Jones acknowledged that Page's production techniques were a key component of the success of Led Zeppelin:

In an interview that Page himself gave to Guitar World magazine in 1993, he remarked on his work as a producer:

Personal lifeRelationshipsDuring the 1960s Page was with American recording artist Jackie DeShannon, who is cited as a possible inspiration for the Page composition and Led Zeppelin recording "Tangerine".[127] French model Charlotte Martin was Page's partner from 1970 to about 1982 or 1983. Page called her "My Lady" and together they had a daughter, Scarlet Page (born in 1971), who is a photographer. While touring with Led Zeppelin, Page's view on groupies was described as "the younger, the better," according to tour manager Richard Cole.[128] For example, Page had a well-documented,[129][130] one-year-long relationship with "baby groupie" Lori Mattix (also known as Lori Maddox), beginning when she was 14 or 15 and while he was 28. In light of the Me Too movement four decades later, their relationship attracted renewed attention.[131][132] From 1986 to 1995, Page was married to Patricia Ecker, a model and waitress. They have a son, James Patrick Page (born April 1988).[133] Page later married Jimena Gómez-Paratcha, whom he met in Brazil on the No Quarter tour.[134] He adopted her oldest daughter Jana (born 1994) and they have two children together: Zofia Jade (born 1997) and Ashen Josan (born 1999).[135][136] Page and Gómez-Paratcha divorced in 2008.[137] Page has been in a relationship with actress and poet Scarlett Sabet, forty-five years his junior, since August 2014.[138] Properties In 1967, when Page was still with The Yardbirds, he purchased the Thames Boathouse on the River Thames in Pangbourne, Berkshire and resided there until 1973. The Boathouse was also the place where Page and Plant first officially got together in the summer of 1968 and Led Zeppelin was formed.[139] In 1972, Page bought the Tower House from Richard Harris. It was the home that William Burges (1827–81) had designed for himself in London. "I had an interest going back to my teens in the pre-Raphaelite movement and the architecture of Burges", Page said. "What a wonderful world to discover." The reputation of Burges rests on his extravagant designs and his contribution to the Gothic revival in architecture in the nineteenth century.[140] From 1980 to 2004 Page owned the Mill House, Mill Lane, Windsor, which was formerly the home of actor Michael Caine. Fellow Led Zeppelin band member John Bonham died at the house in 1980. From the early 1970s to the early 1990s, Page owned the Boleskine House, the former residence of occultist Aleister Crowley.[141][142] Sections of Page's fantasy sequence in the film The Song Remains the Same were filmed at night on the mountainside directly behind Boleskine House.  Page also previously owned Plumpton Place in Sussex, formerly owned by Edward Hudson, the owner of Country Life magazine and with certain parts of the house designed by Edwin Lutyens. This house features in the Zeppelin film The Song Remains The Same where Page is seen sitting on the lawn playing a hurdy-gurdy. He currently resides in Sonning, Berkshire in Deanery Garden, a house also designed by Edwin Lutyens for Edward Hudson. Recreational drug usePage has acknowledged heavy recreational drug use throughout the 1970s. In an interview with Guitar World magazine in 2003, he stated: "I can't speak for the [other members of the band], but for me drugs were an integral part of the whole thing, right from the beginning, right to the end."[143] After the band's 1973 North American tour, Page told Nick Kent: "Oh, everyone went over the top a few times. I know I did and, to be honest with you, I don't really remember much of what happened."[144] In 1975, Page began to use heroin, according to Richard Cole. Cole claims that he and Page took the drug during the recording sessions of the album Presence, and Page admitted shortly afterward that he was addicted to the drug.[145] By Led Zeppelin's 1977 North American tour, Page's heroin addiction was beginning to hamper his guitar playing performances.[6][126][146] By this time the guitarist had lost a noticeable amount of weight. His onstage appearance was not the only obvious change; his addiction caused Page to become so inward and isolated it altered the dynamics between him and Plant considerably.[147] During the recording sessions for In Through the Out Door in 1978, Page's diminished influence on the album (relative to bassist and keyboardist John Paul Jones) is partly attributed to his heroin addiction, which resulted in his absence from the studio for long periods of time.[148] Page reportedly overcame his heroin habit in the early 1980s,[149] although he was arrested for possession of cocaine in both 1982 and 1984.[150][151][152] He was given a 12-month conditional discharge in 1982 and, despite a second offence usually carrying a jail sentence, he was only fined.[153] In a 1988 interview with Musician magazine, Page took offence when the interviewer noted that heroin had been associated with his name and insisted: "Do I look as if I'm a smack addict? Well, I'm not. Thank you very much."[32] In an interview he gave to Q magazine in 2003, Page responded to a question as to whether he regrets getting so involved in heroin and cocaine:

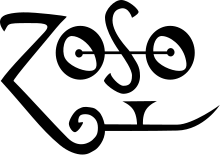

Interest in the occultPage's interest in the occult started as a schoolboy at the age of fifteen, when he read English occultist's Aleister Crowley's Magick in Theory and Practice. He later said that following this discovery, he thought: "Yes, that's it. My thing: I've found it."[28] The appearance of four symbols on the jacket of Led Zeppelin's fourth album has been linked to Page's interest in the occult.[155] The four symbols represented each member of the band. Page's own so-called "Zoso" symbol originated in Ars Magica Arteficii (1557) by Gerolamo Cardano, an old alchemical grimoire, where it has been identified as a sigil consisting of zodiac signs. The sigil is reproduced in Dictionary of Occult, Hermetic and Alchemical Sigils by Fred Gettings.[156][157] During tours and performances after the release of the fourth album, Page often had the "Zoso" symbol embroidered on his clothes, along with zodiac symbols. These were visible most notably on his "Dragon Suit", which included the signs for Capricorn, Scorpio and Cancer which are Page's Sun, Ascendant and Moon signs, respectively. The "Zoso" symbol also appeared on Page's amplifiers. The artwork inside the album cover of Led Zeppelin IV is from a painting attributed to the artist Barrington Colby, influenced by the traditional Rider/Waite Tarot card design for the card called "The Hermit". Very little is known about Colby and rumours have persisted down the years that Page himself is responsible for the painting.[155] Page transforms into this character during his fantasy sequence in Led Zeppelin's concert film The Song Remains the Same. In the early 1970s Page owned an occult bookshop and publishing house, The Equinox Booksellers and Publishers, at 4 Holland Street in Kensington, London, named after Crowley's biannual magazine, The Equinox.[158] The design of the interior incorporated Egyptian and Art Deco motifs, with Crowley's birth chart affixed to a wall. Page's reasons for setting up the bookshop were straightforward:

The company published two books: a facsimile of Crowley's 1904 edition of The Goetia[159] and Astrology, A Cosmic Science by Isabel Hickey.[160] The lease eventually expired on the premises and was not renewed. As Page said: "It obviously wasn't going to run the way it should without some drastic business changes, and I didn't really want to have to agree to all that. I basically just wanted the shop to be the nucleus, that's all."[161] Page has maintained a strong interest in Crowley for many years. In 1978, he explained:

Page was commissioned to write the soundtrack music for the film Lucifer Rising by Crowley admirer and underground movie director Kenneth Anger. Page ultimately produced 23 minutes of music, which Anger felt was insufficient because the film ran for 28 minutes and Anger wanted the film to have a full soundtrack. Anger claimed Page took three years to deliver the music and the final product was only 23 minutes of "droning". The director also slammed the guitarist in the press by calling him a "dabbler" in the occult and an addict and being too strung out on drugs to complete the project. Page countered that he had fulfilled all his obligations, even going so far as to lend Anger his own film editing equipment to help him finish the project.[163] Page released the Lucifer Rising music on vinyl in 2012 via his website on "Lucifer Rising and other sound tracks". Side one contained "Lucifer Rising – Main Track", whilst side two contained the tracks "Incubus", "Damask", "Unharmonics", "Damask – Ambient", and "Lucifer Rising – Percussive Return". In the December 2012 Rolling Stone cover story "Jimmy Page: The Rolling Stone Interview", Page said: "... there was a request, suggesting that Lucifer Rising should come out again with my music on. I ignored it."[164] Although Page collected works by Crowley, he has never described himself as a Thelemite nor was he ever initiated into Ordo Templi Orientis.[citation needed] The Equinox Bookstore and Boleskine House were both sold off during the 1980s, as Page settled into family life and participated in charity work.[citation needed] DiscographyWith Led Zeppelin:

With Roy Harper:

With the Firm:

Solo:

With Coverdale–Page:

with Page and Plant:

ReferencesCitations

Works cited

Further reading

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||