|

John Henry Wright

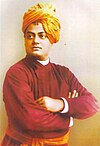

John Henry Wright (February 4, 1852 – November 25, 1908)[1] was an American classical scholar born at Urumiah (Rezaieh), Persia.[2] He earned his Bachelors (1873) and Masters (1876) at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire. After junior appointments (first in Ohio and then at Dartmouth) in 1886 he joined Johns Hopkins as a professor of classical philology. In 1887, he became a professor of Greek at Harvard, where, from 1895 to 1908, he was also Dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Some of Wright's most notable works are A History of All Nations from the Earliest Times (1905), a 24–volume history of the world; the translations Masterpieces of Greek literature (1902); and The Origin of Plato's Cave (1906). He was active in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philological Association, and similar organizations. From 1889 to 1906 he co-edited the Classical Review (later Classical Quarterly) and from 1897 to 1906 he was chief editor of the American Journal of Archaeology. In 1893 Wright met the Indian Hindu monk Swami Vivekananda, who greatly influenced him;[3] Wright described Vivekananda as "more learned than all our learned professors put together."[4] Wright received LL.D.s from Dartmouth and Case Western Reserve University in 1901. He died on 25 November 1908 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[2] Early life Wright was born on 4 February 1852 in Urumiah, Persia. His father, Dr. Austin Hazen Wright (1811-1865) was a medical missionary (Dartmouth alumnus, 1830) in Persia from 1840 to 1865, with an interest in archaeology;[2][5][6] and an Oriental scholar.[2] Wright's mother was Catherine Myers Wright (1821-1888).[1] Wright's older sister was the classical archaeologist, Lucy Myers Wright Mitchell.[6] In 1873, Wright obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree from Dartmouth College and three years later, he obtained his Master of Arts degree from the same school. Afterwards he studied Sanskrit for two years (1876–1878) at the University of Leipzig. He received LL.D.s from both Dartmouth and Western Reserve University in 1901.[1][2] His teachers included Georg Curtius and Franz Overbeck.[1] CareerIn 1873, he worked in Ohio Agricultural and Mechanical College (now known as Ohio State University) as an associate professor of ancient languages (Greek and Latin), being part of the school's first faculty. Teaching graduate studies and doing research in classical antiquity were his forte, which brought him fame. As there was a dearth of faculty to teach his specialization of classical archaeology and Greek history, he created courses on these subjects. He left in 1876.[1] In 1878, he joined Dartmouth College as an associate professor where he taught Greek and German, working at Dartmouth till 1886.[1] In 1886, he was appointed professor of classical philology and Dean of the Collegiate Board of Johns Hopkins, and a year later was assigned as professor of Greek at Harvard; in 1895 he became Dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.[7] He retained the post at Harvard till 1908.[1] In 1906, he went to Athens, Greece and worked as an annual professor at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens until 1907.[1] Scholarly worksWright wrote, edited and translated many books, monographs and scholarly papers. Some of his earlier notable works are— An Address on the Place of Original Research in Collegiate Education (1882), The College in the University and Classical Philology in the College (1886), translation of Collignon's Manual of Greek Archæology (1886), etc.[2] An Address on the Place of Original Research in Collegiate Education was a lecture which he delivered on 7 October 1886, at the opening of the eleventh academic year of Johns Hopkins College.[8] In the same year, he translated A manual of Greek archaeology written by Maxime Collignon to English.[9] In 1892, Wright wrote The Date of Cylon. Though Wright wrote it in 1892, it remained unpublished until Aristotle's work on the Constitution of the Athenians was discovered; this resulted in confirming his recording of the "Chronology of Events in Athens" of the seventh century.[1][2] In 1893, he wrote a paper named Herondaea, which contained valuable research works on the recently discovered papyrus of Herondas. In 1894, his "Studies in Sophocles" was published.[2] In 1902, Wright edited and published Masterpieces of Greek literature. In this book, he translated and published selections of most notable Greek literature including works of Homer, Tyrtaeus, Archilochus, Callistratus, Alcaeus, Sappho, Anacreon, Pindar, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes, Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Plato, Theocritus and Lucian. The book also included short biographical sketches on these philosophers and writers and explanatory notes and analysis.[10] In 1904, he read a paper "Present Problems of the History of the Classical Literature'" at the Congress of Arts and Sciences at the St. Louis Exposition.  In 1905, he served as editor, translator and supervisor on A History of All Nations from the Earliest Times in twenty-four volumes.[2] The other notable scholars who were involved in this project were Ferdinand Justi, Sara Yorke Stevenson, and Morris Jastrow. The History of All Nations consisted of 24 volumes– five were on Antiquity, five on history of the Middle Ages, ten on history of the modern world, two on history of America, and remaining two volumes were comprehensive index volumes of the series. The scholars wrote, they wanted to write a "history of mankind", which required collaboration of many editors and scholars.[11] In 1906, Wright published "The Origin of Plato's Cave," an outgrowth of his interest in the archaeological excavations of the Cave of Vari on Mt. Hymettus near Athens.[1] In this article he deals with the antecedents of the allegory of the cave that the philosopher introduced in the opening of the seventh book of the Republic. Wright demonstrated that the attributes of the allegorical cave closely matched the actual one; he concluded they were likely based on it, with the possible influence of additional elements from the Empedocles' poem Purifications and the Quarry-Grottos of Syracuse.[12] Other activitiesIn 1893, he became a fellow of American Association of Arts and Sciences. In the same year he was a member of Archaeological Institute of America. In 1894, he became president of the American Philological Association. He was also a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[2] He was a member of New England Classical Association and was the president at its first annual meeting which was held in Springfield in April, 1906.[1] He worked as a co-editor of Classical Review from 1889 to 1906 and then of its successor Classical Quarterly in 1907. From 1897 to 1906 he was the chief editor of the American Journal of Archaeology.[1] He was also one of the notable contributing editors to the classical section of the Twentieth Century Text Books.[2] Personal lifeHe married, on 2 April 1879 in Gambier, Ohio, Mary Tappan Wright, the daughter of Eli Todd Tappan, president of Kenyon College. Mary was a prominent novelist, author of Aliens (1902), The Test (1904), The Tower (1906), and The Charioteers (1912). The couple had three children, Elizabeth Tappan Wright (who died at a young age); legal scholar and utopian author Austin Tappan Wright; and the geographer John Kirtland Wright. They resided in Hanover, New Hampshire, Baltimore, Maryland and Cambridge, Massachusetts, in that order with their residency in the last interrupted by a period in Athens.[13] Wright died on 25 November 1908 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was survived by his wife and sons.[2] LegacyWright is considered as one of the most eminent American scholars of the nineteenth century. According to C. B. Gullick "His range in teaching was encyclopaedic, and a keen critical sense, fortified with wide reading, gave him what seemed like the power of divination in interpreting difficult texts".[1] He maintained excellent rapport with his students and was well known for his humour, catholicity and unbiased assessments.[1] Wright's American contemporaries included Henry Simmons Frieze, Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, William Watson Goodwin, William Gardner Hale, William Sanders Scarborough, and Thomas Day Seymour, some of whom allied themselves with other academics which ultimately developed the discipline of the "humanities". Wright and his contemporaries wrote memorable works which gained international attention for American classicists of this era.[14] Because of his contributions to Maxime Collignon's Manuel d'Archeologie Grecque and the classes he offered at Harvard, White was considered a pioneer in the US in the teaching of classical archaeology.[15] Relationship with Swami Vivekananda In 1893, Swami Vivekananda went to the United States to the Parliament of the World's Religions as a delegate of Hinduism and India. After reaching Chicago on 30 July 1893 he learned that no one could attend the Parliament as delegate without credential or bona fide. He did not have one at that moment and he felt utterly disappointed. He also learned the Parliament would not open till first week of September. But, Vivekananda did not give up his hope. To cut his expenditure he decided to go to Boston which was less costly than Chicago.[4] On August 25, 1893, at Boston, Vivekananda met Wright for the first time.[3] Wright was amazed by Vivekananda's profound knowledge and urged him to attend the upcoming Parliament as a speaker. He was so much astonished that he invited Vivekananda to stay in his house as a guest. From August 25 to 27, 1893, Vivekananda stayed at Wright's house at 8 Arlington Street.[3] When Vivekananda told Wright that he did not have any credential or bona fide to attend the Parliament he reportedly told him— "To ask you, Swami, for your credentials is like asking the sun about its right to shine." Then Wright himself wrote a letter of introduction to the chairman of the Parliament of the World's Religion and suggested to him to invite Vivekananda as a speaker stating — "Here is a man who is more learned than all our learned professors put together."[4][16][17] Wright also learned that Vivekananda did not have enough money to buy a railway ticket, so, he bought him a railway ticket too.[18] Even after the conclusion of the Parliament, they kept in touch with each other through correspondence.[19] Vivekananda remained ever thankful to Wright for his help and kindness. In a letter written on 18 June 1894, Vivekananda addressed Wright as brother and wrote — "Stout hearts like yours are not common, my brother. This is a queer place — this world of ours. On the whole I am very very thankful to the Lord for the amount of kindness I have received at the hands of the people of this country — I, a complete stranger here without even 'credentials'. Everything works for the best."[20] References

Sources

Bibliography

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||