|

Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)

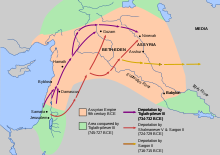

The Kingdom of Israel (Hebrew: מַמְלֶכֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל Mamleḵeṯ Yīśrāʾēl), also called the Northern Kingdom or the Kingdom of Samaria, was an Israelite kingdom that existed in the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. Its beginnings date back to the first half of the 10th century BCE.[2] It controlled the areas of Samaria, Galilee and parts of Transjordan; the former two regions underwent a period in which a large number of new settlements were established shortly after the kingdom came into existence.[3] It had four capital cities in succession: Shiloh, Shechem, Tirzah, and the city of Samaria. In the 9th century BCE, it was ruled by the Omride dynasty, whose political centre was the city of Samaria. According to the Hebrew Bible, the territory of the Twelve Tribes of Israel was once amalgamated under a Kingdom of Israel and Judah, which was ruled by the House of Saul and then by the House of David. However, upon the death of Solomon, who was the son and successor of David, there was discontent over his son and successor Rehoboam, whose reign was only accepted by the Tribe of Judah and the Tribe of Benjamin. The unpopularity of Rehoboam's reign among the rest of the Israelites, who sought Jeroboam as their monarch, resulted in Jeroboam's Revolt, which led to the establishment of the Kingdom of Israel in the north (Samaria), whereas the loyalists of Judah and Benjamin kept Rehoboam as their monarch and established the Kingdom of Judah in the south (Judea), ending Israelite political unity. While the existence of Israel and Judah as two independent kingdoms is not disputed, some historians and archaeologists reject the historicity of the Kingdom of Israel and Judah.[Notes 1] Around 720 BCE, Israel was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[4] The records of Assyrian king Sargon II indicate that he deported 27,290 Israelites to Mesopotamia.[5][6] This deportation resulted in the loss of one-fifth of the kingdom's population and is known as the Assyrian captivity, which gave rise to the notion of the Ten Lost Tribes. Some of these Israelites, however, managed to migrate to safety in neighbouring Judah,[7] though the Judahites themselves would be conquered by the Neo-Babylonian Empire nearly two centuries later. Those who stayed behind in Samaria following the Assyrian conquest mainly concentrated themselves around Mount Gerizim and eventually came to be known as the Samaritans.[8][9] The Assyrians, as part of their historic deportation policy, also settled other conquered foreign populations in the territory of Israel.[9] History According to Israel Finkelstein, Shoshenq I's campaign in the second half of the 10th century BCE collapsed the early polity of Gibeon in central highlands, and made possible the beginning of the Northern Kingdom, with its capital at Shechem,[10][11] around 931 BCE. Israel consolidated as a kingdom in the first half of 9th century BCE,[12] with its capital at Tirzah first,[13] and next at the city of Samaria since 880 BCE. The existence of this Israelite state in the north is documented in 9th century BCE inscriptions.[14] The earliest mention is from the Kurkh stela of c. 853 BCE, when Shalmaneser III mentions "Ahab the Israelite", plus the denominative for "land", and his ten thousand troops.[15] This kingdom would have included parts of the lowlands (the Shephelah), the Jezreel plain, lower Galilee and parts of the Transjordan.[15] Ahab's forces were part of an anti-Assyrian coalition, implying that an urban elite ruled the kingdom, possessed a royal and state cult with large urban temples, and had scribes, mercenaries, and an administrative apparatus.[15] In all this, it was similar to other recently founded kingdoms of the time, such as Ammon and Moab.[15] Samaria is one of the most universally accepted archaeological sites from the biblical period.[16] In around 840 BCE, the Mesha Stele records the victory of Moab (in today's Jordan), under King Mesha, over Israel, King Omri and his son Ahab.[17] Archaeological finds, ancient Near Eastern texts, and the biblical record testify that in the time of the Omrides, Israel ruled in the mountainous Galilee, at Hazor in the upper Jordan Valley, in large parts of Transjordan between the Wadi Mujib and the Yarmuk, and in the coastal Sharon plain.[18] In Assyrian inscriptions, the Kingdom of Israel is referred to as the "House of ʻOmri".[15] The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III mentions Jehu, son of ʻOmri.[15] The Neo-Assyrian emperor Adad-nirari III did an expedition into the Levant around 803 BCE mentioned in the Nimrud slab, which comments he went to "the Hatti and Amurru lands, Tyre, Sidon, the mat of Hu-um-ri "land of ʻOmri", Edom, Philistia, and Aram (not Judah)."[15] The Tell al-Rimah stela of the same king introduces a third way of talking about the kingdom, as Samaria, in the phrase "Joash of Samaria".[19] The use of Omri's name to refer to the kingdom still survived, and was used by Sargon II in the phrase "the whole house of Omri" in describing his conquest of the city of Samaria in 722 BCE.[20] It is significant that the Assyrians never mention the Kingdom of Judah until the end of the 8th century, when it was an Assyrian vassal state: possibly they never had contact with it, or possibly they regarded it as a vassal of Israel/Samaria or Aram, or possibly the southern kingdom did not exist during this period.[21] In the Hebrew Bible One traditional source for the history of the Kingdom of Israel has been the Hebrew Bible, especially the Books of Kings and Chronicles. These books were written by authors in Jerusalem, the capital of the Kingdom of Judah. Being written in a rival kingdom, they were inspired by ideological and theological viewpoints that influence the narrative.[18] Anachronisms, legends and literary forms also affect the story. Some of the recorded events are believed to have occurred long after the destruction of the kingdom of Israel. Biblical archaeology has both confirmed and challenged parts of the biblical account.[18] According to the Hebrew Bible, there existed a United Kingdom of Israel (the United Monarchy), ruled from Jerusalem by David and his son Solomon, after whose death Israel and Judah separated into two kingdoms. The first mention of the name Israel is from an Egyptian inscription, the Merneptah Stele, dating from the Late Bronze Age (c. 1208 BCE); this gives little solid information, but indicates that the name of the later kingdom was borrowed rather than originating with the kingdom itself.[22] Relationship with the Kingdom of JudahAccording to the Hebrew Bible, for the first sixty years after the split, the kings of Judah tried to re-establish their authority over the northern kingdom, and there was perpetual war between them. For the following eighty years, there was no open war between them, as, for the most part, Judah had engaged in a military alliance with Aram-Damascus, opening a northern front against Israel.[23] The conflict between Israel and Judah was temporarily settled when Jehoshaphat, King of Judah, allied himself with the reigning house of Israel, Ahab, through marriage. Later, Jehosophat's son and successor, Jehoram of Judah, married Ahab's daughter Athaliah, cementing the alliance.[23] However, the sons of Ahab were slaughtered by Jehu following his coup d'état around 840 BCE.[24] From Hazael to Jeroboam IIAfter being defeated by Hazael, Israel began a period of progressive recovery following the campaigns against Aram-Damascus of Adad-nirari III.[25] This ultimately led to a period of major territorial expansion under Jeroboam II, who extended the kingdom's possessions throughout the Northern Transjordan. Following Jeroboam II's death, the Kingdom experienced a period of decline as a result of sectional rivalries and struggles for the throne.[26] Conquest by the Neo-Assyrian Empire (732–720 BCE) In c. 732 BCE, King Pekah of Israel, while allied with Rezin, king of Aram, threatened Jerusalem. Ahaz, King of Judah, appealed to Tiglath-Pileser III, the King of Assyria, for help. After Ahaz paid tribute to Tiglath-Pileser,[27] Tiglath-Pileser sacked Damascus and Israel, annexing Aram[28] and the territories of the tribes of Reuben, Gad and Manasseh in Gilead, including the desert outposts of Jetur, Naphish and Nodab. People from these tribes, including the Reubenite leader, were taken captive and resettled in the region of the Khabur River system, in Halah, Habor, Hara and Gozan (1 Chronicles 5:26). Tiglath-Pilesar also captured the territory of Naphtali and the city of Janoah in Ephraim, and an Assyrian governor was placed over the region of Naphtali. According to 2 Kings 16:9 and 2 Kings 15:29, the population of Aram and the annexed part of Israel was deported to Assyria.[29]  The remainder of the northern kingdom of Israel continued to exist within the reduced territory as an independent kingdom until around 720 BCE, when it was again invaded by Assyria and more of the population was deported. Not all of Israel's populace was deported by the Assyrians. During the three-year siege of Samaria in the territory of Ephraim by the Assyrians, Shalmaneser V died and was succeeded by Sargon II, who himself records the capture of that city thus: "Samaria I looked at, I captured; 27,280 men who dwelt in it I carried away" into Assyria. Thus, around 720 BCE, after two centuries, the northern kingdom came to an end. Some of the Israelite captives were resettled in the Khabur region, and the rest in the land of the Medes, thus establishing Hebrew communities in Ecbatana and Rages. The Book of Tobit additionally records that Sargon had taken other captives from the northern kingdom to the Assyrian capital of Nineveh, in particular Tobit from the town of Thisbe in Naphtali.[citation needed] The Hebrew Bible relates that the population of the Kingdom of Israel was exiled, becoming known as the Ten Lost Tribes. To the south, the Tribe of Judah, the Tribe of Simeon (that was "absorbed" into Judah), the Tribe of Benjamin and the people of the Tribe of Levi, who lived among them of the original Israelite nation, remained in the southern Kingdom of Judah. The Kingdom of Judah continued to exist as an independent state until 586 BCE, when it was conquered by the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Samaritan traditionThe tradition of the Samaritan people states that much of the population of the Kingdom of Israel remained in place after the Assyrian captivity, including the Tribes of Naphtali, Manasseh, Benjamin and Levi – being the progenitors of the modern Samaritans. In their book The Bible Unearthed, Israeli authors Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman estimate that only a fifth (about 40,000) of the population of the Kingdom of Israel were actually resettled out of the area during the two deportation periods under Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II.[5]: 221 Many members of these northern tribes also fled south to the Kingdom of Judah. Jerusalem seems to have expanded in size five-fold during this period, requiring a new wall to be built, and a new source of water Siloam to be provided by King Hezekiah.[7] Recorded accounts In their book The Bible Unearthed, Israeli authors Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman estimate that only a fifth (about 40,000) of the population of the northern Kingdom of Israel were actually resettled out of the area during the two deportation periods under Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II.[5] No known non-Biblical record exists of the Assyrians having exiled people from four of the tribes of Israel: Dan, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun. Descriptions of the deportation of people from Reuben, Gad, Manasseh, Ephraim and Naphtali indicate that only a portion of these tribes were deported, and the places to which they were deported are known locations given in the accounts. The deported communities are mentioned as still existing at the time of the composition of the Books of Kings and Chronicles and did not disappear by assimilation. 2 Chronicles 30:1–18 explicitly mentions northern Israelites who had been spared by the Assyrians, in particular people of Ephraim, Manasseh, Asher, Issachar and Zebulun, and how members of the latter three returned to worship at the Temple in Jerusalem during the reign of Hezekiah.[33]  ReligionThe religious climate of the Kingdom of Israel appears to have followed two major trends. The first was the worship of Yahweh; the religion of ancient Israel is sometimes referred to by modern scholars as Yahwism.[34] The Hebrew Bible, however, states that some of the northern Israelites also adored Baal (see 1 Kings 16:31 and the Baal cycle discovered at Ugarit).[34] The reference in Hosea 10 to Israel's "divided heart"[35] may refer to these two cultic observances, although alternatively it may refer to hesitation between looking to Assyria and Egypt for support.[36] The Jewish Bible also states that Ahab allowed the cult worship of Baal to become acceptable of the kingdom. His wife Jezebel was the daughter of the Phoenician king of Tyre and a devotee to Baal worship (1 Kings 16:31).[37] Dynasties

According to the Bible, the Northern Kingdom had 19 kings across 9 different dynasties throughout its 208 years of existence.  Mentions of Israel/Samaria in Assyrian literature and inscriptionsThe table below lists all the historical references to the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria) in Assyrian records.[38] King Omri's name takes the Assyrian shape of "Humri", his kingdom or dynasty that of Bit Humri or alike—the "House of Humri/Omri".

See also

ReferencesNotes

Citations

Sources

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Kingdom of Israel.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||