|

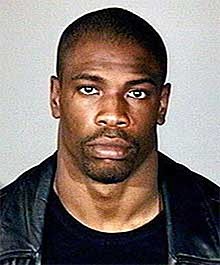

Lawrence Phillips

Lawrence Lamond Phillips (May 12, 1975 – January 13, 2016) was an American professional football running back who played in the National Football League (NFL) for three seasons. A highly touted collegiate prospect, Phillips' professional career was cut short by legal troubles that continued up until his death. Phillips won the 1995 Orange Bowl and the 1996 Fiesta Bowl playing college football for the Nebraska Cornhuskers, which led to him being selected sixth overall in the 1996 NFL draft by the St. Louis Rams. However, his frequent legal problems and inconsistent performances resulted in the Rams releasing him near the end of the 1997 season. After playing only two games for the Miami Dolphins, Phillips pursued a comeback with the San Francisco 49ers in 1999, but was released due to questions over his work ethic. He last played professionally in the Canadian Football League (CFL) for two seasons with the Montreal Alouettes and Calgary Stampeders. With the Alouettes in 2002, Phillips was named an All-Star and won the Grey Cup before further legal problems and work ethic concerns ended his career the next season. Remaining in trouble with the law, Phillips was serving a 31-year sentence on assault convictions when he was charged in 2015 for murdering his cellmate. While awaiting trial, he was found dead in solitary confinement, which was ruled a suicide. Early lifePhillips was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, and later moved to California, where he grew up in foster homes. He attended West Covina High School in West Covina, California for his freshman and sophomore years. He was a varsity starter both on offense as a running back and defense as an outside linebacker. He then attended Baldwin Park High School in Baldwin Park, California for his junior and senior years, and his team won a CIF championship his junior season, which attracted the attention of colleges, including the University of Nebraska. College careerIn 1993, his freshman year at University of Nebraska, Phillips gradually worked his way up the player ranks. He came off the bench to rush for 137 yards and a touchdown in the Cornhuskers' 14–13 win against Pac-10 champion UCLA. In the second half of the 1994 Orange Bowl, he sparked the Husker ground game, carrying 13 times for 64 of the 183 rushing yards against a formidable Seminole defense. All but one of Phillips' carries came in the fourth quarter, during which he scored on a 12-yard touchdown run. This game established him as the primary running back in the Cornhuskers’ offense. By his sophomore year, Phillips became the focal point of the offense because of injuries to quarterbacks Tommie Frazier and Brook Berringer. He tied a school record by rushing for 100 yards or more in 11 straight games in 1994 despite frequently playing against eight or nine-man defensive fronts. Against the #3 Miami Hurricanes, Phillips had 96 yards on 19 carries, including a 25-yard run that was the longest rushing play the Hurricanes had allowed all season. During the regular season, he ran for 1,722 yards, still a Nebraska record for a sophomore. Phillips' performance in the Orange Bowl that year was key to Nebraska securing its undefeated season and the national championship in 1994. Less than two weeks after Phillips helped Nebraska win the 1994 championship, he pleaded not guilty to charges of assault, vandalism, and disturbing the peace. The charges came from a March 1994 incident, in which Phillips was accused of grabbing a 21-year-old college student "around the neck". Phillips entered a pretrial diversion program earlier, but was charged on November 18, 1994, after failing to complete the requirements of the program.[1] Shortly before the start of the next season, Phillips' eligibility was in question for receiving a $100 lunch from a sports agent during the 1994 season.[2] When Nebraska officials became aware of the violation, he allegedly reimbursed the agent. The NCAA ruled him eligible just in time for the season opener, but continued to investigate other unspecified issues involving Phillips.[3] When the 1995 season finally arrived, Phillips became an early front-runner for the Heisman Trophy. In Nebraska's second game of the season, against Michigan State—playing its first game under new coach Nick Saban—Phillips had 206 rushing yards and four touchdowns on 22 carries. After only two games, he was averaging more than 11 yards per carry and had scored six touchdowns. Hours after the team returned from East Lansing on September 10, 1995, Phillips broke into backup quarterback Scott Frost's apartment by climbing the outside of the building to the third floor and entering through some sliding doors. He then assaulted his ex-girlfriend, basketball player Kate McEwen. Phillips dragged McEwen out of the apartment by the hair and down three flights of stairs before smashing her head into a mailbox. Phillips was subsequently arrested, and eventually suspended by head coach Tom Osborne. The case became a source of controversy and media attention, with the perception that Osborne was coddling a star player by not kicking Phillips off the team permanently. Osborne walked out on a press conference when asked, "If one of your players had roughed up a member of your family and had dragged her down a flight of steps, would you have reinstated that player to the team?"[4] Outraged Nebraska faculty proposed that any student convicted of a violent crime should be prohibited from representing the university on the football field.[5] Osborne defended the decision, saying that abandoning Phillips might do more harm than good, stating the best way to help Phillips was within the structured environment of the football program. Osborne stated, "I felt the only thing I could put in a place that would keep him on track was football, because that was probably the only consistent organizing factor in his life."[6] After a six-game suspension, Osborne reinstated Phillips for the Iowa State game,[7] although touted freshman Ahman Green continued to start. Phillips also played against Kansas and Oklahoma. Despite pressure from the national media, Osborne named Phillips the starter for the Fiesta Bowl, which pitted No. 1 Nebraska against No. 2 Florida for the national championship. In the game, Phillips rushed for 165 yards and two touchdowns on 25 carries and scored a touchdown on a 16-yard reception in the Cornhuskers' 62–24 victory. The performance boosted Phillips' draft stock. With Osborne's encouragement, he decided to turn pro a year early.[8]

Notes - Statistics include bowl game performances. Professional football career

NFL draftAt the 1996 NFL draft, teams had to decide if Phillips' talent was worth the risk, considering his character issues. Based solely on football talent, he was considered a top five, perhaps even number one pick.[10] He was widely expected to be selected by the new Baltimore Ravens with the fourth pick to fill their vacant running back position.[11] However, Baltimore decided to select the best available player regardless of position, and with the fourth pick they selected offensive tackle (and future Hall of Famer) Jonathan Ogden. During the draft, ESPN analyst Joe Theismann stated in regard to Phillips: "Everybody's called him the best player in the draft."[12] St. Louis RamsPhillips was drafted in the first round with the sixth overall pick by the St. Louis Rams.[13] The Rams thought so highly of Phillips that on the same day of the draft, they traded his predecessor, future Pro Football Hall of Fame running back Jerome Bettis, to the Pittsburgh Steelers.[14] On July 29, 1996, Phillips signed a three-year, $5.625-million contract. He received no signing bonus, but his salaries were $1.5 million in 1996, $1.875 million in 1997 and $2.25 million in 1998. Also, he had a chance to receive some guaranteed money in the future if he met certain conditions.[15] The chaos he created at Nebraska continued in St. Louis; in less than two years with the Rams, he spent 23 days in jail.[16] In 1996, Phillips played in 15 games with 11 starts. He carried the ball 193 times for 632 yards and 4 touchdowns. In 1997, Phillips surpassed his entire 1996 total in only 10 games and nine starts, rushing for 634 yards. However, on November 20, the Rams abruptly released him. According to reports at the time, Rams team officials told the press that coach Dick Vermeil told Phillips that he was being demoted to second string due to his inconsistent performance and inability to stay out of trouble. Phillips stormed out of the Rams' facility and missed that day's meeting and practice. The Rams lost patience with him and decided to cut ties with him.[17] A teary-eyed Vermeil at the time said Phillips was potentially the best running back he ever coached.[18] In the 2016 documentary Running For His Life: the Lawrence Phillips Story, Vermeil revealed that Phillips collapsed on the field during pre-game warmup for his 10th (and final) game with the 1997 Rams. Trainers revealed that he had alcohol on his breath, and told Vermeil that Philips had smelled of alcohol on a number of previous occasions. He was known to stay in bars until 4 a.m. on the night before games. The following Monday, Vermeil called Phillips into his office and told him that he was cutting him. While Vermeil was known for having little tolerance for off-the-field misconduct, he knew Phillips was a talented player and gave him numerous chances to stay on the right path. He did say, though, that if given the chance to do it over again, he would have kept Phillips on the roster.[19][20] In that same film, Vermeil revealed that he reached out to a friend, Miami Dolphins head coach Jimmy Johnson, to give Phillips a chance with the Dolphins. Miami DolphinsPhillips lasted two games in Miami, rushing for 44 yards on 18 carries for a 2.4 yard-per-carry average. The Dolphins released him after he pleaded no contest to assaulting a woman at a Plantation, Florida nightclub.[16] NFL EuropePhillips missed the 1998 season before attempting a comeback in 1999; he set NFL Europe offensive records with the Barcelona Dragons (1,021 yards and 14 touchdowns) and attracted interest from several NFL teams. San Francisco 49ersPhillips returned stateside with the San Francisco 49ers in the fall of 1999. The 49ers interviewed him several times before seemingly being assured that his past difficulties were behind him, though general manager Bill Walsh told him that the 49ers would cut him if he stepped out of line. He contended for the starting job before pulling a hamstring in training camp. Additionally, his blocking left much to be desired. He was beaten out for the starting spot by Charlie Garner.[16] He did, however, become the 49ers' primary kick returner.[21] Although Phillips stayed out of trouble off the field, his on-field performance was of greater concern to the 49ers. His blocking skills were so suspect that he was almost never in the game on passing downs.[16] Their concerns were validated during Week 3's Monday Night Football game against the Arizona Cardinals, when cornerback Aeneas Williams rushed in on a blitz and Phillips did not pick it up. Williams knocked Steve Young unconscious on the play with a hard but clean hit. Young suffered a career-ending concussion; he did not play again that season and had to retire. In the same game, Phillips ran for a 68-yard touchdown to put the game away 24–10, outrunning Williams to the end zone. Nonetheless, his missed block on Williams led the 49ers to question his work ethic.[22] By November, the 49ers began to lose patience with Phillips. According to coach Steve Mariucci, Phillips began losing interest early in the season, to the point that he was finding "reasons and ways why he shouldn't practice." The situation came to a head in the run-up to the 49ers' game against the New Orleans Saints. Phillips refused to practice on November 10 and 12 and openly mocked coaching directives. Mariucci called a staff meeting at which Phillips' position coach Tom Rathman threatened to stay in San Francisco if Phillips made the trip. That night, the 49ers suspended Phillips for three games for conduct detrimental to the team.[21][22][23] Walsh said soon thereafter that he could not envision Phillips playing another down for the 49ers. On November 16, Mariucci announced that the 49ers would cut ties with Phillips at the first opportunity.[23] Mariucci stated that the 49ers did not release Phillips right away only because his signing bonus would have counted against the team's salary cap for 1999, tying up nearly all their cap room.[21] Finally, on November 23, 1999, the 49ers waived him.[23] AFL and CFLIn 2001, Phillips signed with the Florida Bobcats of the Arena Football League. However, before playing a down for them, he was released after leaving the team without telling his coach. Phillips then moved on to the Canadian Football League (CFL). He had some difficulty getting a Canadian work visa due to his criminal record, but was eventually cleared to join the Montreal Alouettes. He showed signs of his old form, notching 1,022 yards, 13 touchdowns, and a spot on the CFL Eastern All-Star Team while helping lead them to the 90th Grey Cup.[24] However, he showed signs of lapsing into his old habits off the field. He walked out on the team at least once during the season, and his agent severed ties with him twice.[25] Phillips briefly held out of training camp before the 2003 season due to a salary dispute. On May 1, shortly after his return, the Alouettes released him for not meeting the team's "minimum behavioural standards." It later emerged that he was charged with sexual assault. Phillips signed with the Calgary Stampeders (rushing for 486 yards on 107 carries and 1 touchdown), but was again released, for arguing with head coach Jim Barker.[24] Career statistics

Legal issues and deathOn August 21, 2005, Phillips was arrested for assault after driving a car into three teenagers following a dispute during a pick-up football game in Los Angeles. At the time, Phillips was wanted by the San Diego Police Department in connection with two alleged domestic abuse incidents involving a former girlfriend,[26] who claimed that Phillips choked her to unconsciousness. In addition, the Los Angeles Police Department was seeking Phillips in connection with an allegation of domestic abuse occurring in Los Angeles. In March 2006, Phillips was ordered to stand trial on charges of felony assault with a deadly weapon stemming from the August 2005 incident. On October 10, 2006, he was found guilty on seven counts. On October 3, 2008, he was sentenced to 10 years in a California state prison;[27] that sentence was subsequently reduced to seven years. While serving that sentence, Phillips was convicted in August 2009 for the assault on his former girlfriend Amaliya Weisler[28] on seven counts, including assault with great bodily injury, false imprisonment, making a criminal threat, and auto theft.[29] On December 18, 2009, Phillips was sentenced to 25 years in prison on the 2009 convictions, to run consecutive to the 2008 sentence, for a total of 31 years.[26][30] Phillips, California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation number G31982, was admitted to Kern Valley State Prison on October 16, 2008.[31] Under California law, since his crimes harmed other persons, he was required to serve at least 85 percent of his sentence before becoming eligible for parole with good behavior, meaning that he would not have even been considered for release until he was 57 years old. On April 12, 2015, Phillips' cellmate, Damion Soward,[32] the cousin of former NFL wide receiver R. Jay Soward, was found dead in the cell the two men shared. Soward, who was serving a sentence of 82 years to life for a murder conviction,[33] was choked to death. On September 1, Phillips was charged with first-degree murder in Soward's death.[34] On November 9, the prosecutor was granted a motion to reconsider whether to seek the death penalty.[35] Phillips was awaiting trial in solitary confinement when he was found unresponsive in his cell by correctional officers around midnight on January 12, 2016. Phillips was pronounced dead at 1:30 a.m. in a suspected suicide. A coroner determined that Phillips hanged himself. He had a do not resuscitate note taped to his chest.[36] The day before, January 11, a judge ruled that there was enough evidence to bind Phillips over for trial in the murder of Soward.[37][38] On January 15, it was announced that Phillips' family agreed to donate his brain to be examined for chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) at Boston University.[39] Phillips' funeral was held on January 23 at Christ's Church of the Valley in San Dimas, California. He was buried at Inglewood Park Cemetery. References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||