|

Liberty Island

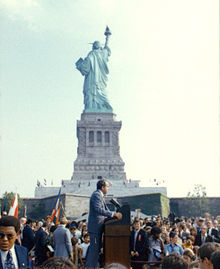

Liberty Island is a federally owned island in Upper New York Bay in the northeastern United States. Its most notable feature is the Statue of Liberty (Liberty Enlightening the World), a large statue by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi that was dedicated in 1886. The island also contains the Statue of Liberty Museum, which opened in 2019 and exhibits the statue's original torch. Long known as Bedloe's Island, it was renamed by an act of the United States Congress in 1956. Part of the State of New York, the island is an exclave of the New York City borough of Manhattan, surrounded by the waters of Jersey City, New Jersey. There were a number of disputes regarding the jurisdictional status of the island during the 20th century. Liberty Island became part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1937 through Presidential Proclamation 2250, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[3] In 1966, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as part of Statue of Liberty National Monument, Ellis Island, and Liberty Island.[4] Geography and accessAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the island has a land area of 14.717 acres (5.956 ha), and is the property of the federal government. Liberty Island is located in the Upper New York Bay within the waters of Jersey City, New Jersey. It is one of the islands that are part of the borough of Manhattan in New York.[5][6][7] The historical developments which led to this construction made Liberty Island an exclave of one state, New York, in another, New Jersey. Liberty Island is 2,000 feet (610 m) east of Liberty State Park in Jersey City and is 1.6 miles (2.6 km) southwest of the Battery in Lower Manhattan. State sovereignty disputes State disputeAn unusual clause in the 1664 colonial land grant that outlined New Jersey's borders reads: "westward of Long Island, and Manhitas Island and bounded on the east part by the main sea, and part by Hudson's river"[8] rather than at the river's midpoint, as was common in other colonial charters.[9] In 1824 the City of New York attempted to assert a jurisdictional monopoly over the growing ferry service in New York Harbor in Gibbons v. Ogden. It was deemed by the court that interstate transport would be regulated by the federal government. This did not resolve the border issue. In 1830, New Jersey planned to bring suit,[10] but the matter was resolved with a compact between the states ratified by Congress in 1834, which set the boundary line between them as the midpoint of the shared waterway.[7][11] This would place Bedloe's (Liberty) Island and Ellis Island in New Jersey; however, the compact included an exception specifying that they remain the territory of New York.[11] This was later confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in a 1908 case which also expounded on the compact.[12]  In 1986 a suit brought by New Jersey residents challenging New York State's jurisdiction over Liberty Island was dismissed.[13] In 1986, U.S. Representative Frank J. Guarini and Gerald McCann, then mayor of Jersey City, sued the government of New York City, contending that New Jersey should have dominion over Liberty Island because it is on the New Jersey side of the state line.[14] Since the court chose not to hear the case,[15] the existing legal status remained unchanged. Portions of the island that are above water are part of New York, while riparian rights to all of the submerged land surrounding the statue belong to New Jersey. The southwestern section, 4.17 acres (1.69 ha),[16] of the island was created by land reclamation.[16][17] In 1998, the United States Supreme Court decided the state jurisdiction of the nearby Ellis Island in New Jersey v. New York. Being mostly constructed of artificial infill, New Jersey argued and the court agreed that the 1834 compact covered only the natural parts of the island, and not the portions added by infill. Thus it was agreed that the parts of the island made of filled land belonged to New Jersey while the original natural part belonged to New York.[18] This proved impractical to administer and New Jersey and New York subsequently agreed to share jurisdiction of the entire island.[10][19] This special situation only applies to Ellis Island and part of Shooters Island.[6] Federal ownership Liberty Island has been owned by the federal government since 1801, first as a military installation and now as a national landmark. Statue of Liberty National Monument, Ellis Island and Liberty Island, listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1966, encompasses land in both states,[20] control of which is superseded by the United States. The undisputed boundary between New Jersey and New York is in the center of the Hudson River and the Upper New York Bay, with Liberty Island situated well on the New Jersey side of the water line with Liberty Island itself an exclave of the State of New York and a part of New York City, allowing the state and city of New York to retain sovereignty of Liberty Island, serve process there and collect sales tax from Liberty Island souvenir shops.[6] In response to a FAQ about whether the Statue of Liberty is in New York or New Jersey, the National Park Service, which oversees Liberty Island, cites the 1834 compact.[20] Question 127 on a naturalization examination piloted in 2006 asks "Where is the Statue of Liberty?" The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services gives "New York Harbor" and "Liberty Island" as preferred answers, but notes that "New Jersey", "New York", "New York City", and "on the Hudson" are acceptable.[21] Both New York City and Jersey City have assigned the island lot numbers. Utility services, including electricity, water, and sewage, to Liberty and Ellis Islands are provided from the New Jersey side, while mail is delivered from the Battery in New York.[22] The statue was featured on New York license plates from 1986 through 2000[23][24] and on a special New Jersey license plate celebrating Liberty State Park in Jersey City. The statue is also seen on the New York state quarter. The national monument was the symbol of the Central Railroad of New Jersey (which operated along the present-day Raritan Valley Line), whose railroad terminal is nearby. Public accessTwo ferry slips are located at the southwestern side of Liberty Island. No charge is made for entrance to the Statue of Liberty National Monument, but there is a cost for the ferry service,[25] as private boats may not dock at the island. A concession was granted in 2007 to Statue Cruises to operate the transportation and ticketing facilities, replacing Circle Line, which had operated the service since 1953.[26] The ferries depart from Liberty State Park in Jersey City and the Battery in Lower Manhattan.[27] History Great Oyster IslandAt the time of European colonization of the Hudson River estuary in the mid-17th century, much of the west side of Upper New York Bay contained large tidal flats which hosted vast oyster beds, a major source of food for the Lenape native people who lived there at the time. Several islands were not completely submerged at high tide. Three of them (later known as Bedloe's/Love/Liberty, Ellis, and Black Tom) were given the name Oyster Islands (oester eilanden) by the Dutch settlers of New Netherland, the first European colony in the Mid-Atlantic states. The oyster beds would remain a major source of food for nearly three centuries.[28] Land reclamation, started by the 1870s, particularly by the Lehigh Valley Railroad and Central Railroad of New Jersey, eventually obliterated the beds, engulfed one island and brought the shoreline much closer to the others.[29] Bedloe's IslandAfter the surrender of Fort Amsterdam by the Dutch to the British in 1664, the English governor Richard Nicolls granted the island to Captain Robert Needham. It was sold to Isaac Bedloe on December 23, 1667. The island was retained by his estate until 1732 when it was sold for five shillings to New York merchants Adolphe Philipse and Henry Lane. During their ownership, the island was temporarily commandeered by the city of New York to establish a smallpox quarantine station.[30][31][32][33] In 1746, Archibald Kennedy (later 11th Earl of Cassilis) purchased the island and a summer residence was established,[34] along with construction of a lighthouse. Seven years later, the island is described in an advertisement (in which "Bedlow's" had become "Bedloe's", along with an alternate name of "Love Island") as being available for rental:

In 1756, Kennedy allowed the island to again be used as a smallpox quarantine station, and on February 18, 1758, the Corporation of the City of New York bought the island for £1,000 for use as a pest house. When the British troops occupied New York Harbor in the lead-up to the American Revolutionary War, the island was to be used for housing for Tory refugees, with HMS Eagle docked next to it, but on April 2, 1776, the buildings constructed on the island for their use were burned to the ground.[35] Fort Wood On February 15, 1800, the New York State Legislature ceded the island to the federal government, for the construction of a defensive fort to be built there (along with Governors Island and Ellis Island). Construction of a fort on the island in the shape of an 11-point star began in 1806 and was completed in 1811, protecting New York from British invasion in the upcoming conflict.[36] The fort is considered part of the second system of U.S. fortifications. Following the War of 1812, the star-shaped fortification was named Fort Wood after Lt. Col Eleazer Derby Wood who was killed in the Siege of Fort Erie in 1814, a major American defensive victory against British troops near the war's end. The granite fortification followed an 11-pointed star fort layout, mounting 24 guns.[37][38] A larger fort mounting 77 guns was proposed under the third system of US fortifications but was not built.[39] By the time it was chosen for the Statue of Liberty in the 1880s, the fort was outmoded and obsolete, disused and its substantial stone walls were then used as the distinctive base for the Statue of Liberty given by the Third French Republic for the American 1876 centenary celebrations. It had become a part of the base for the Statue of Liberty after the island was first seen by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, the statue's sculptor. The National Park Service (which had been created in 1916) took over operations of the island in two stages: 2 acres (8,100 m2) in 1933, and the remainder in 1937.[3] The military installation was completely removed by 1944.[40][41]: 91–92 Statue of LibertyThe statue, entitled Liberty Enlightening the World,[42] was a gift from the people of France to mark the American Centennial. It was agreed that the Congress would authorize the acceptance of the statue by the President of the United States, and that the War Department would facilitate its construction and presentation.[43] The construction of the statue was completed in France in July 1884. The cornerstone was laid on August 5, 1884, and after some funding delays, construction of the pedestal was finished on April 22, 1886. The statue arrived in New York Harbor on June 17, 1885, on board the French frigate Isère,[44] was stored for eleven months in crates waiting for its pedestal to be finished, and was then reassembled in four months. On October 28, 1886, the Statue of Liberty was unveiled by President Grover Cleveland. The name Liberty Island was made official by Congress in 1956.[45] Museums American Museum of ImmigrationThe American Museum of Immigration formerly operated at Liberty Island. It was dedicated on September 26, 1972, in a ceremony presided over by President of the United States Richard Nixon.[46] The museum closed in 1991 following the opening of the Ellis Island Immigration Museum.[41]: 19 Statue of Liberty MuseumOn October 7, 2016, construction started on the new Statue of Liberty Museum on Liberty Island. The new $70 million, 26,000-square-foot (2,400 m2) museum is able to accommodate all of the island's visitors, as opposed to the former museum, which only 20 percent of the island's daily visitors could visit.[47] The original torch is located here along with exhibits relating to the statue's construction and history. There is a theater where visitors can watch an aerial view of the statue.[47][48] The museum, designed by FXFOWLE Architects, is integrated with the parkland around it.[48] It is being funded privately by Diane von Fürstenberg, Michael Bloomberg, Jeff Bezos, Coca-Cola, NBCUniversal, the family of Laurence Tisch and Preston Robert Tisch, Mellody Hobson, and George Lucas.[49] Von Fürstenberg headed the fundraising for the museum, and the project raised more than $40 million in fundraising as of groundbreaking.[48] The museum opened on May 16, 2019.[50][51] See also

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Liberty Island.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||