|

List of possible dwarf planets

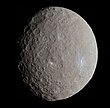

The number of dwarf planets in the Solar System is unknown. Estimates have run as high as 200 in the Kuiper belt[1] and over 10,000 in the region beyond.[2] However, consideration of the surprisingly low densities of many large trans-Neptunian objects, as well as spectroscopic analysis of their surfaces, suggests that the number of dwarf planets may be much lower, perhaps only nine among bodies known so far.[3][4] The International Astronomical Union (IAU) defines dwarf planets as being in hydrostatic equilibrium, and notes six bodies in particular: Ceres in the inner Solar System and five in the trans-Neptunian region: Pluto, Eris, Haumea, Makemake, and Quaoar.[5] Only Pluto and Ceres have been confirmed to be in hydrostatic equilibrium, due to the results of the New Horizons and Dawn missions.[6] Eris is generally assumed to be a dwarf planet because it is similar in size to Pluto and even more massive. Haumea and Makemake were accepted as dwarf planets by the IAU for naming purposes and will keep their names if it turns out they are not dwarf planets. Smaller trans-Neptunian objects have been called dwarf planets if they appear to be solid bodies, which is a prerequisite for hydrostatic equilibrium: planetologists generally include at least Gonggong, Orcus, and Sedna. In practice the requirement for hydrostatic equilibrium is often loosened to include all gravitationally rounded objects, even by the IAU, as otherwise even Mercury would not be a planet. Quaoar has been accepted as a dwarf planet under a 2022–2023 annual report. Limiting values Beside directly orbiting the Sun, the qualifying feature of a dwarf planet is that it have "sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid-body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape".[7][8][9] Current observations are generally insufficient for a direct determination as to whether a body meets this definition. Often the only clues for trans-Neptunian objects (TNO) is a crude estimate of their diameters and albedos. Icy satellites as large as 1,500 km in diameter have proven to not be in equilibrium, whereas dark objects in the outer solar system often have low densities that imply they are not even solid bodies, much less gravitationally controlled dwarf planets. Ceres, which has a significant amount of ice in its composition, is the only accepted dwarf planet in the asteroid belt, though there are unexplained anomalies.[10] 4 Vesta, the second-most-massive asteroid and one that is basaltic in composition, appears to have a fully differentiated interior and was therefore in equilibrium at some point in its history, but no longer is today.[11] The third-most massive object, 2 Pallas, has a somewhat irregular surface and is thought to have only a partially differentiated interior; it is also less icy than Ceres. Michael Brown has estimated that, because rocky objects such as Vesta are more rigid than icy objects, rocky objects below 900 kilometres (560 mi) in diameter may not be in hydrostatic equilibrium and thus not dwarf planets.[1] The two largest icy outer-belt asteroids 10 Hygiea and 704 Interamnia are close to equilibrium, but in Hygiea's case this may be a result of its disruption and the re-aggregation of its fragments, while Interamnia is now somewhat away from equilibrium due to impacts.[10][12] Based on a comparison with the icy moons that have been visited by spacecraft, such as Mimas (round at 400 km in diameter) and Proteus (irregular at 410–440 km in diameter), Brown estimated that an icy body relaxes into hydrostatic equilibrium at a diameter somewhere between 200 and 400 km.[1] However, after Brown and Tancredi made their calculations, better determination of their shapes showed that Mimas and the other mid-sized ellipsoidal moons of Saturn up to at least Iapetus (which, at 1,471 km in diameter, is approximately the same size as Haumea and Makemake) are no longer in hydrostatic equilibrium; they are also icier than TNOs are likely to be. They have equilibrium shapes that froze in place some time ago, and do not match the shapes that equilibrium bodies would have at their current rotation rates.[13] Thus Rhea, at 1528 km in diameter, is the smallest body for which gravitational measurements are consistent with current hydrostatic equilibrium. Ceres, at 950 km in diameter, is close to equilibrium, but some deviations from equilibrium shape remain unexplained.[14] Much larger objects, such as Earth's moon and the planet Mercury, are not near hydrostatic equilibrium today,[15][16][17] though the Moon is composed primarily of silicate rock and Mercury of metal (in contrast to most dwarf planet candidates, which are ice and rock). Saturn's moons may have been subject to a thermal history that would have produced equilibrium-like shapes in bodies too small for gravity alone to do so. Thus, at present it is unknown whether any trans-Neptunian objects smaller than Pluto and Eris are in hydrostatic equilibrium.[3] Nonetheless, it does not matter in practice, because the precise statement of hydrostatic equilibrium in the definition is universally ignored in favour of roundness and solidity.[3][18] The majority of mid-sized TNOs up to about 900–1000 km in diameter have significantly lower densities (~ 1.0–1.2 g/ml) than larger bodies such as Pluto (1.86 g/cm3). Brown had speculated that this was due to their composition, that they were almost entirely icy. However, Grundy et al.[3] point out that there is no known mechanism or evolutionary pathway for mid-sized bodies to be icy while both larger and smaller objects are partially rocky. They demonstrated that at the prevailing temperatures of the Kuiper Belt, water ice is strong enough to support open interior spaces (interstices) in objects of this size; they concluded that mid-size TNOs have low densities for the same reason that smaller objects do—because they have not compacted under self-gravity into fully solid objects, and thus the typical TNO smaller than 900–1000 km in diameter is (pending some other formative mechanism) unlikely to be a dwarf planet. Assessment by TancrediIn 2010, Gonzalo Tancredi presented a report to the IAU evaluating a list of 46 trans-Neptunian candidates for dwarf planet status based on light-curve-amplitude analysis and a calculation that the object was more than 450 kilometres (280 mi) in diameter. Some diameters were measured, some were best-fit estimates, and others used an assumed albedo of 0.10 to calculate the diameter. Of these, he identified 15 as dwarf planets by his criteria (including the 4 accepted by the IAU), with another 9 being considered possible. To be cautious, he advised the IAU to "officially" accept as dwarf planets the top three: Sedna, Orcus, and Quaoar.[19] Although the IAU had anticipated Tancredi's recommendations, by late 2023 only Quaoar had been accepted. Assessment by Brown

Mike Brown considers 130 trans-Neptunian bodies to be "probably" dwarf planets, ranked them by estimated size.[20] He does not consider asteroids, stating "in the asteroid belt Ceres, with a diameter of 900 km, is the only object large enough to be round."[20] The terms for varying degrees of likelihood he split these into:

Beside the five older accepted by the IAU plus Quaoar, the 'nearly certain' category includes Gonggong, Sedna, Orcus, 2002 MS4, and Salacia. Note that although Brown's site claims to be updated daily, these largest objects haven't been updated since late 2013, and indeed the current best diameter estimates for Salacia and 2002 MS4 are less than 900 km. (Orcus is just above the threshold.)[21] Assessment by Grundy et al.Grundy et al. propose that dark, low-density TNOs in the size range of approximately 400–1000 km are transitional between smaller, porous (and thus low-density) bodies and larger, denser, brighter, and geologically differentiated planetary bodies (such as dwarf planets). Bodies in this size range should have begun to collapse the interstitial spaces left over from their formation, but not fully, leaving some residual porosity.[3] Many TNOs in the size range of about 400–1000 km have oddly low densities, in the range of about 1.0–1.2 g/cm3, that are substantially less than those of dwarf planets such as Pluto, Eris and Ceres, which have densities closer to 2. Brown has suggested that large low-density bodies must be composed almost entirely of water ice since he presumed that bodies of this size would necessarily be solid. However, this leaves unexplained why TNOs both larger than 1,000 km and smaller than 400 km, and indeed comets, are composed of a substantial fraction of rock, leaving only this size range to be primarily icy. Experiments with water ice at the relevant pressures and temperatures suggest that substantial porosity could remain in this size range, and it is possible that adding rock to the mix would further increase resistance to collapsing into a solid body. Bodies with internal porosity remaining from their formation could be at best only partially differentiated, in their deep interiors (if a body had begun to collapse into a solid body, there should be evidence in the form of fault systems from when its surface contracted). The higher albedos of larger bodies are also evidence of full differentiation, as such bodies were presumably resurfaced with ice from their interiors. Grundy et al.[3] propose therefore that mid-size (< 1,000 km), low-density (< 1.4 g/cm3) and low-albedo (< ~0.2) bodies such as Salacia, Varda, Gǃkúnǁʼhòmdímà, and (55637) 2002 UX25 are not differentiated planetary bodies like Orcus, Quaoar, and Charon. The boundary between the two populations would appear to be in the range of about 900–1000 km, although Grundy et al. also suggest that 600–700 km might constitute an upper limit to retaining significant porosity.[3] If Grundy et al.[3] are correct, then very few known bodies in the outer Solar System are likely to have compacted into fully solid bodies, and thus to possibly have become dwarf planets at some point in their past or to still be dwarf planets at present. Pluto–Charon, Eris, Haumea, Gonggong, Makemake, Quaoar, and Sedna are either known (Pluto) or strong candidates (the others). Orcus is again just above the threshold by size, though it is bright. There are a number of smaller bodies, estimated to be between 700 and 900 km in diameter, for most of which not enough is known to apply these criteria. All of them are dark, mostly with albedos under 0.11, with brighter 2013 FY27 (0.18) an exception; this suggests that they are not dwarf planets. However, Salacia and Varda may be dense enough to at least be solid. If Salacia were spherical and had the same albedo as its moon, it would have a density of between 1.4 and 1.6 g/cm3, calculated a few months after Grundy et al.'s initial assessment, though still an albedo of only 0.04.[22] Varda might have a higher density of 1.78±0.06 g/cm3 (a lower density of 1.23±0.04 g/cm3 was considered possible though less probable), published the year after Grundy et al.'s initial assessment;[23] its albedo of 0.10 is close to Quaoar's. Assessment by Emery et al.In 2023, Emery et al. wrote that near-infrared spectroscopy by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in 2022 suggests that Sedna, Gonggong, and Quaoar internally melted and differentiated and are chemically evolved, like the larger dwarf planets Pluto, Eris, Haumea, and Makemake, but unlike "all smaller KBOs". This is because light hydrocarbons are present on their surfaces (e.g. ethane, acetylene, and ethylene), which implies that methane is continuously being resupplied, and that methane would likely come from internal geochemistry. On the other hand, the surfaces of Sedna, Gonggong, and Quaoar have low abundances of CO and CO2, similar to Pluto, Eris, and Makemake but in contrast to smaller bodies. This suggests that the threshold for dwarf planethood in the trans-Neptunian region is a diameter of ~900 km (thus including only Pluto, Eris, Haumea, Makemake, Gonggong, Quaoar, Orcus, and Sedna), and that even Salacia may not be a dwarf planet.[4] Likeliest dwarf planetsThe assessments of the IAU, Tancredi et al., Brown, and Grundy et al. for some of potential dwarf planets are as follows. For the IAU, the acceptance criteria were for naming purposes; Quaoar was called a dwarf planet in a 2022–2023 IAU annual report.[24] An IAU question-and-answer press release from 2006 was more specific: it estimated that objects with mass above 5×1020 kg and diameter greater than 800 km (800 km across) would "normally" be in hydrostatic equilibrium ("the shape ... would normally be determined by self-gravity"), but that "all borderline cases would need to be determined by observation."[25] This is close to Grundy et al.'s suggestion for the approximate limit. Several of these objects had not yet been discovered when Tancredi et al. did their analysis. Brown's sole criterion is diameter; he accepts significantly many more as "highly likely" to be dwarf planets, for which his threshold is 600 km (see below). Grundy et al. did not determine which bodies were dwarf planets, but rather which could not be. A red Two moons are included for comparison: Triton formed as a TNO, and Charon is larger than some dwarf planet candidates.

Largest measured candidatesThe following trans-Neptunian objects have measured diameters at least 600 kilometres (370 mi) to within measurement uncertainties; this was the threshold to be considered a "highly likely" dwarf planet in Brown's early assessment. Grundy et al. speculated that 600 km to 700 km diameter could represent "the upper limit to retain substantial internal pore space", and that objects around 900 km could have collapsed interiors but fail to completely differentiate.[3] The two satellites of TNOs that surpass this threshold have also been included: Pluto's moon Charon and Eris' moon Dysnomia. The next largest TNO moon is Orcus' moon Vanth at 442.5±10.2 km and a poorly constrained (87±8)×1018 kg, with an albedo of about 8%. Ceres, generally accepted as a dwarf planet, is added for comparison. Also added for comparison is Triton, which is thought to have been a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt before it was captured by Neptune. Bodies with very poorly known sizes (e.g. 2018 VG18 "Farout") have been excluded. Complicating the situation for poorly known bodies is that a body assumed to be a large single object might turn out to be a binary or ternary system of smaller objects, such as 2013 FY27 or Lempo. A 2021 occultation of 2004 XR190 ("Buffy") found a chord of 560 km: if the body is approximately spherical, it is likely that the diameter is greater than 560 km, but if it is elongated, the mean diameter may well be less. Explanations and sources for the measured masses and diameters can be found in the corresponding articles linked in column "Designation" of the table.

All of these categories are subject to change with further evidence.

Brightest unmeasured candidatesFor objects without a measured size or mass, sizes can only be estimated by assuming an albedo. Most sub-dwarf objects are thought to be dark, because they haven't been resurfaced; this means that they are also relatively large for their magnitudes. Below is a table for assumed albedos between 4% (the albedo of Salacia) and 20% (a value above which suggests resurfacing), and the sizes objects of those albedos would need to be (if round) to produce the observed absolute magnitude. Backgrounds are blue for >900 km and teal for >600 km.

See also

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||