|

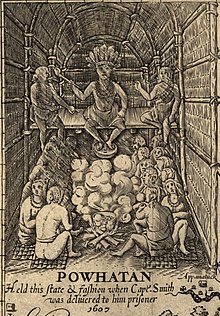

Longhouses of the Indigenous peoples of North America  Longhouses were a style of residential dwelling built by Native American and First Nations peoples in various parts of North America. Sometimes separate longhouses were built for community meetings. Iroquois and the other East Coast longhousesThe Iroquois (Haudenosaunee or "People of the Longhouses"), who reside in the Northeastern United States as well as Central Canada (Ontario and Quebec), built and inhabited longhouses. These were sometimes more than 75 m (246 ft) in length but generally around 5 to 7 m (16 to 23 ft) wide. Scholars believe walls were made of sharpened and fire-hardened poles (up to 1,000 saplings for a 50 m (160 ft) house) driven close together into the ground. Strips of bark were woven horizontally through the lines of poles to form more or less weatherproof walls. Poles were set in the ground and braced by horizontal poles along the walls. The roof is made by bending a series of poles, resulting in an arc-shaped roof. This was covered with leaves and grasses. The frame is covered by bark that is sewn in place and layered as shingles, and reinforced by light swag.  Doors were constructed at both ends and were covered with an animal hide to preserve interior warmth. Especially long longhouses had doors in the sidewalls as well. Longhouses featured fireplaces in the center for warmth. Holes were made above the hearth to let out smoke, but such smoke holes also let in rain and snow. Ventilation openings, later singly dubbed as a smoke pipe, were positioned at intervals, possibly totalling five to six along the roofing of the longhouse. Missionaries who visited these longhouses often wrote about their dark interiors. On average a typical longhouse was about 24.4 by 5.5 by 5.5 m (80 by 18 by 18 ft) and was meant to house up to twenty or more families, most of whom were matrilineally related. The people had a matrilineal kinship system, with property and inheritance passed through the maternal line. Children were born into the mother's clan. Protective palisades were built around the dwellings; these stood 4.3 to 4.9 m (14 to 16 ft) high, keeping the longhouse village safe. Tribes or ethnic groups in northeast North America, south and east of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, which had traditions of building longhouses include the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee): Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida and Mohawk. The Wyandot (also called Huron) and Erie people, both Iroquoian peoples, also built longhouses, as did the Algonquian peoples, such as the Lenni Lenape, who lived from western New England in Connecticut, along the lower Hudson River, and along the Delaware River and both sides of the Delaware Bay. The Pamunkey of the Algonquian-speaking Powhatan Confederacy in Virginia also built longhouses. Although the Shawnee were not known to build longhouses, colonist Christopher Gist describes how, during his visit to Lower Shawneetown in January 1751, he and Andrew Montour addressed a meeting of village leaders in a "Kind of State-House of about 90 Feet [27 m] long, with a light Cover of Bark in which they hold their Councils."[1] Northwest Coast longhouses  The indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest of North America also built a form of longhouse. Theirs were built with logs or split-log frame, and covered with split log planks, and sometimes an additional bark cover. Cedar is the preferred lumber. The wealthy built extraordinarily large longhouses. Old Man House, built by the Suquamish, at what became the Port Madison Squamish Reservation, was 152 by 12–18 m (500 by 40–60 ft), c. 1850.[2][3] Usually one doorway faces the shore. Each longhouse contains a number of booths along both sides of the central hallway, separated by wooden containers (akin to modern drawers). Each booth has its own individual hearth and fire. Usually an extended family occupied one longhouse, and cooperated in obtaining food, building canoes, and other daily tasks. The gambrel roof was unique to the Coast Salish of Puget Sound.[2] The front is often very elaborately decorated with an integrated mural of numerous drawings of faces and heraldic crest icons of raven, bear, whale, etc. A totem pole often was erected outside the longhouse. The style varies greatly, and sometimes it became part of the entrance way. Tribes or ethnic groups along the North American Pacific coast with some sort of longhouse building traditions include the Haida, Tsimshian, Tlingit Makah, Clatsop, Coast Salish and Multnomah. Excavations at Ozette, WashingtonFrom beneath mudflows dating back to about 1700, archaeologists have recovered timbers and planks. In the part of one house where a woodworker lived, tools were found and also tools in all stages of manufacture. There were even wood chips. Where a whaler lived, there lay harpoons and also a wall screen carved with a whale. Benches and looms were inlaid with shell, and there were other indications of wealth. A single house had five separate living areas centered on cooking hearths; each had artifacts that revealed aspects of the former occupants' lives. More bows and arrows were found at one living area than any of the others, an indication that hunters lived there. Another had more fishing gear than other subsistence equipment, and at another, more harpoon equipment. Some had everyday work gear, and few elaborately ornamented things. The whaler's corner was just the opposite. The houses were built so that planks on the walls and roofs could be taken off and used at other places, as the people moved seasonally. Paired uprights supported rafters, which, in turn, held roof planks that overlapped like tiles. Wall planks were lashed between sets of poles. The position of these poles depended on the lengths of the boards they held, and they were evidently set and reset through the years the houses were occupied. Walls met at the corners by simply butting together. They stayed structurally independent, allowing for easy dismantling. There were no windows. Light and ventilation came by shifting the position of roof planks, which were simply weighted with rocks, not fastened in position. Benches raised above the floor on stakes provided the main furniture of the houses. They were set near the walls. Cuts and puncture marks indicated they served as work platforms; mats rolled out onto them tie with elders' memories of such benches used as beds. Storage was concentrated behind the benches, along the walls and in corners between benches. These locations within the houses have yielded the most artifacts. The rafters must have also provided storage, but the mudflow carried away this part of the houses. Bibliography

See also

References

External links

Further reading |