|

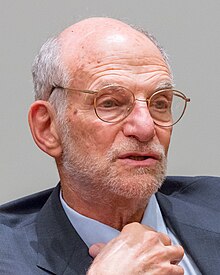

Michael Rosbash

Michael Morris Rosbash (born March 7, 1944) is an American geneticist and chronobiologist. Rosbash is a professor and researcher at Brandeis University[1] and investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Rosbash's research group cloned the Drosophila period gene in 1984 and proposed the Transcription Translation Negative Feedback Loop[2] for circadian clocks in 1990. In 1998, they discovered the cycle gene, clock gene, and cryptochrome photoreceptor in Drosophila through the use of forward genetics, by first identifying the phenotype of a mutant and then determining the genetics behind the mutation. Rosbash was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 2003. Along with Michael W. Young and Jeffrey C. Hall, he was awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries of molecular mechanisms controlling the circadian rhythm".[3][4] LifeMichael Rosbash was born in Kansas City, Missouri. His parents, Hilde and Alfred Rosbash, were Jewish refugees who left Nazi Germany in 1938.[5] His father was a cantor, which, in Judaism, is a person who chants worship services. Rosbash's family moved to Boston when he was two years old, and he has been an avid Red Sox fan ever since. Initially, Rosbash was interested in mathematics but an undergraduate biology course at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and a summer of working in Norman Davidson's lab steered him towards biological research. Rosbash graduated from Caltech in 1965 with a degree in chemistry, spent a year at the Institut de Biologie Physico-Chimique in Paris on the Fulbright Scholarship, and obtained a doctoral degree in biophysics in 1970 from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology under Sheldon Penman. After spending three years on a postdoctoral fellowship in genetics at the University of Edinburgh, Rosbash joined the Brandeis University faculty in 1974. Rosbash is married to fellow scientist Nadja Abovich and he has a stepdaughter named Paula and daughter named Tanya.[6] ResearchRosbash's research initially focused on the metabolism and processing of mRNA; mRNA is the molecular link between DNA and protein. After arriving at Brandeis, Rosbash collaborated with co-worker Jeffrey Hall[7] and investigated the genetic influences on circadian rhythms of the internal biological clock. They used Drosophila melanogaster to study patterns of activity and rest. In 1984, Rosbash and Hall cloned the first Drosophila clock gene, period. Following work done by post-doctoral fellow, Paul Hardin, in discovering that period mRNA and its associated protein (PER) had fluctuating levels during the circadian cycle, in 1990 they proposed a Transcription Translation Negative Feedback Loop (TTFL) model as the basis of the circadian clock.[8] Following this proposal, they looked into the elements that make up other parts of the clock. In May 1998, Rosbash et al. found a homolog for mammalian Clock that performed the same function of activating the transcription of per and tim that they proceeded to call dClock.[9] Also in May 1998, Rosbash et al. discovered in Drosophila the clock gene cycle, a homolog of the mammalian bmal1 gene.[10] In November 1998, Rosbash et al. discovered the cryb Drosophila mutant, which led to the conclusion that cryptochrome protein is involved in circadian photoreception.[11] Chronology of major discoveries

mRNA researchRosbash began studying mRNA processing as a graduate student at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His work in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae has revealed the enzymes, proteins, and subcellular organelles and their convergence upon mRNA in a specific order in order to translate mRNA into proteins. Missteps in this process have been linked to diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, so this work is essential for better understanding and treatment of diseases.[12] Discovery of circadian TTFL in DrosophilaIn 1990, Rosbash, Hall, and Hardin discovered the role of the period gene (per) in the Drosophila' circadian oscillator. They found that PER protein levels fluctuate in light dark cycles, and these fluctuations persist in constant darkness. Similarly, per mRNA abundance also has rhythmic expression that entrains to light dark cycles. In the fly head, per mRNA levels oscillate in both 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycles as well as in constant darkness. Per mRNA levels peaked at the beginning of the subjective night followed by a peak in PER protein levels about 6 hours later. Mutated per genes affected the cycling of per mRNA. From this experimental data, Rosbash, Hall, and Hardin hypothesized that PER protein is involved in a negative feedback loop[2] that controls per mRNA levels, and that this transcription-translation feedback loop is a central feature of the Drosophila circadian clock.[8] They also looked at two other single missense period mutations, perS and perL1. These mutations cause the peak of the evening activity to occur earlier and later, respectively, compared to wildtype per+ flies. They found that RNA levels for perS and perL1 also display clear rhythmicity. Like locomotor activity the peak expression is shifted earlier for perS and later for perL1.[8] They transformed the period0 null mutation flies with a 7.2-kb piece of functional per DNA, and measured per mRNA levels at the per0 locus and new locus. Following transformation, per mRNA levels were rhythmic at both the original and new locus. The per0 locus was able to transcribe normal per mRNA and translate normal PER protein, meaning that rhythmicity was rescued by functional PER protein transcribed and translated from the 7.2-kb piece of per DNA. There is a feedback loop at play in which cycling of PER protein levels at the new locus feeds back to dictate cycling of per mRNA levels at the original per0 locus.[8] In 1992, Rosbash again collaborated with Jeffrey Hall and Paul Hardin to more closely examine the mechanisms of the TTFL. They wondered specifically about the regulation of period mRNA level fluctuations, and found that per mRNA levels were transcriptionally regulated. This was supported by the evidence that per precursor RNA cycles with the same phase as mature transcripts, and oscillate with respect to Zeitgeber Time (ZT). Other evidence for transcriptional regulation is that per gene promoter is sufficient to confer cycling to heterologous mRNA.[13] Challenges to the TTFL model in DrosophilaThe Akhilesh Reddy group has shown, using a range of unbiased -omics techniques (RNA-sequencing, proteomics, metabolomics) that Drosophila S2 cells display circadian molecular rhythms.[14] These cells do not express known "clock genes" including per and tim.[14][15][16] Introduction of PER and TIM proteins into the cells does not cause rhythmicity of these cells as read out by abundance or phosphorylation of PER and TIM proteins.[16][17] These cells were thus regarded as "clock-less" by the fly field until now.[17][16] These findings substantiate the work above in demonstrating the TTFL model of the fly clockwork cannot explain the generation of circadian rhythms.[14] Discovery of Drosophila Clock GeneA likely homolog of the previously discovered mouse gene Clock was identified by Rosbash et al. by cloning of the Drosophila gene defined by the Jrk mutation. This gene was given the name Drosophila Clock. dClock has been shown to interact directly with the per and tim E-boxes and contributes to the circadian transcription of these genes. The Jrk mutation disrupts the transcription cycling of per and tim. It also results in completely arrhythmic behavior in constant darkness for homozygous mutants and about half demonstrated arrhythmic behavior in heterozygotes. The Jrk homozygotes expressed low, non-cycling levels of per and tim mRNA as well as PER and TIM protein. From this, it was concluded that the behavioral arrhythmicity in Jrk was due to a defect in the transcription of the per and tim. This indicated that dClock was involved in the transcriptional activation of per and tim.[9] Discovery of Drosophila Cycle GeneIn 1998, Rosbash et al. discovered the novel clock gene cycle, a homolog of the mammalian Bmal1 gene. Homozygous cycle0 mutants are arrhythmic in locomotor activity and heterozygous cycle0/+ flies have robust rhythms with an altered period of rhythmicity. Western blot analysis shows that homozygous cycle0 mutants have very little PER and TIM protein as well as low per and tim mRNA levels. This indicates that lack of cycle leads to decreased transcription of per and tim genes. Meiotic mapping placed cyc on the third chromosome. They discovered bHLH-PAS domains in cyc, indicating protein binding and DNA binding functions.[10] Discovery of cryptochrome as a Drosophila circadian photoreceptorIn 1998, Rosbash et al. discovered a Drosophila mutant exhibiting flat, non-oscillating levels of per and tim mRNA, due to a null mutation in the cryptochrome gene. This mutation was dubbed crybaby, or cryb. The failure of cryb mutants to synchronize to light dark cycles indicates that cryptochrome’s normal function involves circadian photoreception.[11]  LNV neurons as principal Drosophila circadian pacemakerIn Drosophila, certain lateral neurons (LNs) have been shown to be important for circadian rhythms, including dorsal (LNd) and ventral (LNV) neurons. LNV neurons express PDF (pigment dispersion factor), which was initially hypothesized to be a clock output signal. Mutants for the pdf neuropeptide gene (pdf01) as well as flies selectively ablated for LNV produced similar behavioral responses. Both entrained to external light cues, but were largely arrhythmic in constant conditions. Some flies in each cases showed weak free-running rhythmicity. These results led the researchers to believe that LNV neurons were the critical circadian pacemaker neurons and that PDF was the principal circadian transmitter.[18] Current researchIn more recent years, Rosbash has been working on the brain-neuronal aspects of circadian rhythms. Seven anatomically distinct neuronal groups have been identified that all express the core clock genes. However, the mRNAs appear to be expressed in a circadian and neuron-specific manner, for which his lab has taken interest in determining whether this provides a link to the distinct functions of certain neuronal groups. He has also researched the effects of light on certain neuronal groups and has found that one subgroup is light-sensitive to lights on (dawn) and another is light-sensitive to lights off (dusk). The dawn cells have been shown to promote arousal while the dusk cells promote sleep.[19] Today, Rosbash continues to research mRNA processing and the genetic mechanisms underlying circadian rhythms. He has also published an amusing reflection on his life in science.[20] Positions

Awards

See alsoReferences

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||