|

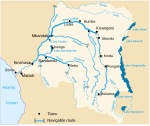

Ndjili River

The Ndjili River (French: Rivière Ndjili) is a river that flows from the south through the capital city of Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where it joins the Congo River. It separates the districts of Tshangu and Mont Amba.[1] The river gives its name to the Ndjili commune and to the Ndjili International Airport.[2] LocationKinshasa lies in a plain surrounded by hills drained by numerous local rivers, of which the Nsele and Ndjili are important tributaries of the Congo River. The climate is tropical, with a dry season and a rainy season.[3] Kinshasa lies just downstream of the Malebo Pool, where the Congo River widens to 25 kilometres (16 mi) across for a length of about 35 kilometres (22 mi). The Malebo Pool has an area of 50,000 hectares (120,000 acres), with the Mbamu island occupying the central part. It is almost 300 metres (980 ft) above sea level, surrounded at some distance by hills that rise to 718 metres (2,356 ft) above sea level. Along the southern shore of the Pool, the land is swampy between the mouths of the Nsele and Ndjili rivers, a distance of 30 kilometres (19 mi), with the swamps covering 10,800 hectares (27,000 acres). The swamps extend 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) inland along the Ndjili.[4] During the colonial era, Jesuits who settled on the Ndjili River in June 1893 at Kimbangu, in what is now Masina, were the first Catholic missionaries in the area. However, within a month they moved away from the unhealthy, swampy conditions that they found to Kimwenza, near the Petites Chutes de la Lukaya[5] These are small falls on the Lukaya River, a tributary of the Ndjili that enters from the west, after running along the southern boundary of present-day Kinshasa. City water supplyThe Ndjili provides the main supply of water to Kinshasa, but tends to be polluted with human waste.[6] Kinshasa had two water treatment stations before independence, one on the Lukunga River and one at Ngaliema bay on the Congo River. By 1985, they were both extremely dilapidated. A new station was built on the Ndikili at Kingbabwe in the Limete commune in two phases, one funded by Belgium in 1971 and the second by Germany in 1982.[7] The French agreed to finance a second station on the Ndjili, but suspended aid to Mobutu in October 1991. A third Ndjili station funded by the Japanese was also cancelled due to the September 1991 lootings. The result was a failure to meet even minimum water supply needs.[8] The river catchment has sandy soils and steep topography, as with other rivers that supply the city. With clearing of the forests, there has been growing soil erosion, leading to sediment pollution. When turbidity levels rise above the 1,000 NTU limit, which has often been reported in the Ndjili and Lukaya rivers during the rainy season, water purification plants have to stop their operations. Imported chemical coagulants and imported lime are needed to keep the plants in operation.[9] On a positive note, after a four-year 51 million euro project financed by the World Bank, in 2009 the Ndjili plant doubled its capacity to 330,000 cubic metres (12,000,000 cu ft) daily, providing nearly 65% of Kinshasa's water supply.[10] Market gardeningIn 1954 the Belgian colonial administration distributed land to women and the unemployed in the marshy region of the Ndijili River in an effort to create a garden peasantry to provide fruit and vegetables to the capital. This practice was revived after independence, trying to meet demand as the city's population expanded from 400,000 in 1969 to an estimated 3.2 million by 1990.[11] The Union of Market Garden Cooperatives of Kinshasa was established on 27 November 1987. There were 32 member cooperatives in 2004, each supporting an agricultural center and managing all the market gardeners working on the site.[12] A 2005 survey showed that most market gardeners were skilled farmers growing crops to make a living. They used manual techniques, the hoe being the main tool. The gardeners had little education and were extremely poor, living in unsanitary conditions. Problems included difficulty in obtaining seeds, fertilizers, farm tools and irrigation water, theft of vegetables during the night, poor roads, infectious diseases, lack of electricity and flooding.[13] Human African trypanosomiasis, or sleeping sickness, is a disease that usually only occurs in rural locations, since it is spread by tsetse flies that need a combination of forest and water to thrive. Between 1970 and 1995, about 39 cases per year were reported in Kinshasa. Numbers of documented cases (which may have been affected by improved screening) jumped to 254 cases in 1996, 226 in 1997, 433 in 1998 and 912 in 1999. Counts of tsetse flies from insect traps along the Ndjili River indicate that market gardening has recreated the conditions needed for active disease transmission.[14] References

Sources

|

||||||||||||||||