|

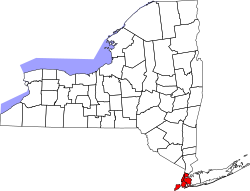

New York City Transit Police

The New York City Transit Police Department was a law enforcement agency in New York City that existed from 1953 (with the creation of the New York City Transit Authority) to 1995, and is currently part of the NYPD. The roots of this organization go back to 1936 when Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia authorized the hiring of special patrolmen for the New York City Subway. These patrolmen eventually became officers of the Transit Police.[1] In 1949, the department was officially divorced from the New York City Police Department, but was eventually fully re-integrated in 1995 as the Transit Bureau of the New York City Police Department by New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani. In 1997, the Transit Bureau became the Transit Division within the newly formed Transportation Bureau. In July 1999, the Transit Division once again became the Transit Bureau, but remained part of the Police Department. Headquarters for the NYPD Transit Bureau are located at 130 Livingston Street in Brooklyn Heights.[2] History Since the 1860s, the New York City Subway's predecessors operated lines running at grade level and on elevated structures. Between 1900 and October 27, 1904, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) built the first subway line in Manhattan. Both the IRT and the competing Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT, later BMT) were privately held operators who operated city-owned subway lines. They hired their own police. However, in 1932, the city-owned Independent Subway System (IND) opened; the IND lines originally had "station supervisors" employed to police them, their names having been taken from the New York City Police Department's hiring list. The creation of the New York City Transit Police came about on November 17, 1933, six men were sworn in as New York State Railway Police. They were unarmed but were still responsible for the safety of the passengers on the IND as well as guarding property. Two years later, 20 "station supervisors, class B" were added for police duty. Responsible for assisting in the opening and closing of doors and announcing destinations, these 26 "specials" were soon given powers of arrest, but only on the IND line. In 1937, 160 more men were added to this police force. Additionally, 3 lieutenants, 1 captain, and 1 inspector from the NYPD were assigned as supervisors. When the privately run IRT and BMT were taken over by New York City in 1940, the small patrol force on the IND line nearly doubled in size. Now part of the Civil Service system, more Transit supervisors were needed. In 1942, the first promotional exam was given for the title of "special patrolman grade 2" – or what is now known as a sergeant. The Code of Criminal Procedure was changed in 1947 granting transit patrolmen peace officer status and by 1950, the number of "specials" reached 563. The following year, exams were held for both Transit sergeants and lieutenants. In 1953, the New York City Transit Authority came into being and assumed control over all the subway lines from the old New York City Board of Transportation. Beginning in 1949, the question as to who should supervise the Transit Police Department was one which was carefully scrutinized over the next five years by various city officials. The issue being considered was, "Should Transit be taken over by the NYPD?" In 1955, the decision was made that the Transit Police Department would become a separate and distinctly different department, ending almost two decades of rule by the NYPD. The Civil Service Commission established a new test for transit recruits, and on April 4, the first appointments from the list were made. An NYPD lieutenant, Thomas O'Rourke, was also designated the first commanding officer of the Transit Police Department. Soon after, Lieutenant O'Rourke along with 9 others, passed the captain's exam. Captain O'Rourke was then appointed as the first chief of the new department. With crime on the rise, the number of transit officers increased so that by 1966, the Department had grown to 2,272 officers. That year, Robert H. Rapp was appointed chief by the NYC Transit Authority. Under Chief Rapp, and at the direction of the mayor, an ambitious new anti-crime program got underway. The program had a goal of assigning an officer to each of New York City's subway trains between the hours of 8:00 PM and 4:00 AM. And the Transit Police Department continued to grow. By early 1975, the department comprised nearly 3,600 members. In 1975, a former NYPD chief inspector and sometime City Council president, Sanford Garelik, was appointed chief of the Transit Police Department.[3] Determined to reorganize the Transit Police Department, Chief Garelik was also successful in instilling a new sense of pride and professionalism among the ranks. However, the fiscal crisis that began that year was an unexpected blow – especially to transit cops. Over the next five years, layoffs and attrition would reduce their numbers to fewer than 2,800. On September 12, 1979, in a sweeping shake up, Chief Garelik was ousted and replaced by Chief James Meehan former Chief of Personnel of NYPD. New officers would not be hired until 1980. By that time, Transit Police was a very old department personnel wise, losing many officers each month to retirement. The first recruits were hired off the list of NYPD exam # 8155 given on June 30, 1979. This first wave of new hires was historic as it contained the first female officers ever sworn into the Transit Police. This required many of the older districts to be renovated to provide locker room facilities for women. Shortly thereafter, Transit Police resumed their own exams. By the early 1990s the Transit Police Department had regained all of its former strength and had increased even further. In 1991, the Transit Police gained federal accreditation[clarification needed] under Chief William Bratton. The department became one of only 175 law-enforcement agencies in the country and only the second in the New York State to achieve that distinction, the other being Suffolk County Police Department. The following year it was also accredited by the State of New York, and by 1994, there were almost 4,500 uniformed and civilian members of the department, making it the sixth-largest police force in the United States. Bratton was also responsible for upgrading the antiquated radio system, changing the service revolvers to a semi-automatic 9mm Glock, and greatly improving the morale of the department. Over time, however, the separation between the NYPD and the NYC Transit Police Department created more and more problems. Redundancy of units, difficulty in communications and differences in procedures all created frustration and inefficiency. As part of his mayoral campaign, candidate Rudolph Giuliani pledged to end the long-unresolved discussion and merge all three of New York City's police departments (the NYPD, the Transit Police, and the New York City Housing Authority Police Department) into a single, coordinated force. Mayor Giuliani took office on January 1, 1994, and immediately appointed William Bratton as NYPD Police Commissioner whose great expertise at police work undertook the mission to fulfill Giuliani's promise. Discussions between the city and the New York City Transit Authority which included a threat of laying off the entire Transit Police Department, produced a memorandum of understanding, and at 12:01 AM on April 2, 1995, the NYC Transit Police was consolidated with the New York City Police Department to become a new bureau within the NYPD called NYPD Transit Bureau. This consolidation is unofficially referred to by some as "The Hostile Takeover Of 95." This term originated with the Transit Police Union, as well as the members of the Transit Police who were opposed to the merger. After a reorganization of the Department in February 1997, the Transit Bureau became the Transit Division within the newly formed Transportation Bureau. In July 1999, the Transit Division once again became the Transit Bureau. The true reasoning behind the consolidation was Giuliani's desire to create one police payroll instead of three separate ones, and to bring all three police departments under his direct control. Prior to April 2, 1995, neither the Transit Police nor the Housing Police was under the purview of the police commissioner, who was in turn the direct subordinate of the mayor. While Members of the Transit Police were paid by the Transit Authority, and those of the Housing Police was paid by the Housing Authority, the funds for the payrolls did not actually come from those agencies, but were provided monthly by The City of New York. Giuliani won his quest for the consolidation by withholding the payroll funds for both police departments. Jobs of the Transit Police One main task of the Transit Police was its defense of the subway system from defacement. Graffiti was very prominent throughout the subway system by the mid-1980s and the city government took a hard line in response. The Transit Police, and specifically a new unit called the Vandal Squad, led by its commanding officer, Lieutenant Kenneth Chiulli, began to fine and arrest those painting graffiti. Founded in 1980, the Vandal Squad's mission was to protect the subway system from serious criminal acts of destruction like kicking out windows and throwing seats out of train cars. It was only with the Clean Car Program of 1984 that graffiti became the primary focus of this specialized unit. They also made a policy to remove any work of graffiti within 24 hours. By the end of the 1980s, the Transit Police had effectively solved the problem of graffiti in the subway system.[4] The Transit Police also handled both quality of life crimes and violent crime in the subway system, with uniform officers, plain clothes anti-crime, as well as a detective squad in each district. While NYPD operated out of precincts, Transit Police operated out of districts with each district covering a different part of the system. Each district had at least 1 RMP patrol car on the surface to provide rapid response to stations requiring police action, and to transport officers with prisoners to central booking, or back to the district. The typical uniformed Transit Police officer worked alone. Plain clothes officers, such as anti-crime, worked in pairs. The Decoy Squad worked in a group, with each member playing a specific role. New hires known as probationary officers were most often assigned to the Tactical Patrol Force known as TPF. The TPF was responsible strictly for train patrol. TPF officers were assigned various trains that they were responsible for during their tour. Patrol required the officers to ride the train for the entire route which meant the TPF crossed both borough lines as well as District lines. At times this caused conflict between the TPF supervisors and the local district supervisors as to who truly had jurisdiction over the TPF. To combat fare evasion, Transit Police had the Summons Squad, whose officers worked in plain clothes in pairs, with the prime objective of issuing summonses system wide for fare evasion, littering and smoking. Prior to the 1990s, all summons issued for fare evasion were appearance tickets in criminal court. The typical penalty was $10 or 2 days. After the creation of the Transit Adjudication Bureau (TAB), summonses were primarily handled by the Transit Adjudication Bureau, a division of New York Civil Court, with the fines going back to the Transit Authority. Even then, Criminal Court summonses could still be issued in lieu of a TAB summons but the TAB summons was the preferred option to help recoup the lost revenue from fare evasion. The Transit Police also had their own internal affairs, with field investigative officers nicknamed "The Shoo-Fly Squad" by the rank and file officers. The shoo-flys would travel throughout the subway system with the express purpose of finding officers committing any form of violation while on post and giving that officer a "complaint". A common warning that a "shoo-fly" was in a particular area would be a radio check followed by a forward and backward count to five. Civilian complaints were handled at 370 Jay Street in Brooklyn. Other specialized Transit Police units included the Emergency Medical Rescue Unit (EMRU) which handled major emergencies on the subway system, the most common being a passenger struck by train, referred to as "man under" if the passenger was run over, "space case" if the passenger had fallen into the gap between the train and the platform, and "dragging" if the passenger had been dragged by the train. A lesser known unit was the Surface Crime Unit (Bus Squad). It consisted of about sixty officers who patrolled the NYC buses and bus depots. There was also a K9 Unit for subway patrol, Vandals Squad to combat graffiti, the Decoy Squad to target robberies, Pickpocket Squad to go after pickpockets, and a Homeless Outreach Unit that would remove homeless persons from the subway and transport them to homeless shelters where various services were offered. Line of duty deathsDuring the existence of the New York City Transit Police Department, 13 officers died in the line of duty.[5]

See also

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||