|

Philosophical pessimism Philosophical pessimism is a philosophical tradition which argues that life is not worth living and that non-existence is preferable to existence. Thinkers in this tradition emphasize that suffering outweighs pleasure, happiness is fleeting or unattainable, and existence itself does not hold inherent value or an intrinsic purpose. Philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer suggest responses to life's suffering, ranging from artistic contemplation and ascetic withdrawal, while Buddhism advocates for spiritual practices. Pessimism often addresses the ethics of both creating and continuing life. Antinatalists assert that bringing new life into a world of suffering is morally wrong, and some pessimists view suicide as a rational response in extreme circumstances; though Schopenhauer personally believed it failed to address the deeper causes of one's suffering. The roots of pessimism trace back to ancient philosophies and religions. Buddhism in Ancient India identifies life as fundamentally marked by suffering (duḥkha), while thinkers like Hegesias of Cyrene in ancient Greece argued that happiness is unattainable due to constant bodily ills and unfulfilled desires. In the beginning of the Common Era, Gnostic Christianity viewed the material world as inherently flawed or evil. Moving into the 19th century, Schopenhauer introduced a systematic philosophy with pessimistic aspects at its core by conceiving of reality as being fundamentally constituted by the "Will" — a ceaseless metaphysical striving that can never be satisfied. Later thinkers, including Julio Cabrera and David Benatar, have expanded on pessimism with contemporary analyses focusing on the empirical life experiences of living beings rather than on metaphysical principles. Critics of pessimism, such as Friedrich Nietzsche, reject its conclusions, instead celebrating struggle and suffering as opportunities for growth and self-transcendence. Pessimism’s influence extends to literature and popular culture. The character of Rust Cohle in the first season of the TV series True Detective embodies a pessimistic worldview, drawing on the works of authors such as Thomas Ligotti, Emil Cioran, and David Benatar. DefinitionsThe word pessimism comes from Latin pessimus, meaning "the worst". The term "optimism" was first used to name Lebnitz's thesis that we live in "the best of all possible worlds"; and "pessimism" was coined to name the opposing view.[1][2]: 222 [3]: 69 [4]: 9 Many scholars of philosophical pessimism characterize it as the view that life is not worth living and that non-existence is preferable to existence.[5]: 4 [6]: 27–29 [7][8]: 1 Some philosophers define pessimism in other ways, emphasizing the claim that the evils in life outweigh the goods[3]: 11, 16, 68–71 [2]: 211 [9]: 350 or present it as "the denial of happiness or the affirmation of life's inherent misery".[10]: 4 ThemesReaching a pessimistic conclusion can be approached in various manners, with numerous arguments reinforcing this perspective. However, certain recurring themes consistently emerge:

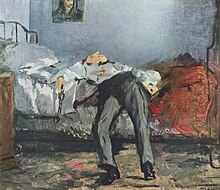

Development of pessimist thoughtPessimistic sentiments can be found throughout religions and in the works of various philosophers. The major developments in the tradition started with the works of German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, who was the first to provide an explanation for why there is so much misery in the world and construct a complete philosophical system in which pessimism played a major role.[5]: 4 [2] Ancient timesOne of the central points of Buddhism, which originated in ancient India, is the claim that life is full of suffering and unsatisfactoriness. This is known as duḥkha from the Four Noble Truths.[16][10]: 38 [17]: 29–42 [18]: 130 In the Ecclesiastes from the Abrahamic religions, which originated in the Middle East, the author laments the meaninglessness of human life,[19] views life as worse than death[20] and expresses antinatalistic sentiments towards coming into existence.[21] These views are made central in Gnosticism, a religious movement stemming from Christianity, where the body is seen as a type of a "prison" for the soul, and the world as a type of hell.[22] Hegesias of Cyrene, who lived in ancient Greece, argued that lasting happiness cannot be realized because of constant bodily ills and the impossibility of achieving all our goals.[23]: 92 19th-century GermanyThe 19th-century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer was the first philosopher who constructed an entire philosophical system, where he presented an explanation of the world through metaphysics, aesthetics, epistemology, and ethics — all connected with a pessimistic view of the world.[5]: 13 [17]: 5 [3]: 335 [2]: 212 Schopenhauer viewed the world as having two sides — Will and representation. Will is pure striving: aimless, incessant, and with no end; it is the inner essence of all things.[24]: 137–163 [25]: 53–54 [26] Representation is how we as organisms view the world with our particular perceptual and cognitive endowment; it is how we build objects from our perceptions.[24]: 105–118 [25]: 17–32 In living creatures, the Will takes the form of the will to life — self-preservation or the survival instinct appearing as striving to satisfy desires.[5]: 51 And since this will to life is our inner nature, we are doomed to be always dissatisfied, as one satisfied desire makes room for striving for yet another object of desire.[13][27][28]: 9–10 There is, however, something we can do with that ceaseless willing. We can take temporary respite during aesthetic contemplation or through cultivating a moral attitude. We can also defeat the will to life more permanently through asceticism, achieving equanimity.[29] 20th and 21st centuriesIn the 20th and 21st centuries, a number of thinkers have revisited and revitalized philosophical pessimism — drawing in large part from the works of Arthur Schopenhauer and his contemporaries. For these writers, pessimism offers anew a metaphysical and ethical perspective from which a contemporary critique of existence might be mounted. Notable 20th and 21st authors who espoused philosophically pessimistic views include Emil Cioran,[30] Peter Wessel Zapffe,[31][32] Eugene Thacker,[33] Thomas Ligotti,[18] David Benatar,[11] Drew M. Dalton,[34] and Julio Cabrera.[35] Main argumentsThe most common arguments for the tenets of philosophical pessimism are briefly presented here.  The three marks of existenceAccording to Buddhism, constant dissatisfaction — duḥkha — is an intrinsic mark of all sentient existence. All living creatures must undergo the sufferings of birth, aging, sickness, and death; they desire what they do not have, seek to avoid what they do not like, and feel loss for the positive things they have lost. These types of striving (taṇhā) are sources of suffering, which are not external but rather inherent vices (such as greed, lust, envy, and self-indulgence) of all living beings.[36] In Buddhism, the concept of duḥkha is closely related to the other two marks of existence: anattā (non-self) and anicca (impermanence). Anattā suggests that there is no permanent, unchanging self; rather, what we consider as the "self" is a collection of changing phenomena. This realization can lead to a deeper understanding of duḥkha, as attachment to a false sense of self contributes to suffering.[37] Anicca, or impermanence, highlights that all things are in a constant state of flux. Everything we experience, including our joys and sorrows, is transient. This impermanence means that clinging to experiences or identities inevitably leads to disappointment and suffering when they change or cease to exist.[38] Together, these three marks of existence illustrate a fundamentally negative view of life from the Buddhist perspective. Since one of the central concepts in Buddhism is that of liberation or nirvana, this highlights the miserable nature of existence — the need to strive for enlightenment through the Noble Eightfold Path emphasizes that life, under this perspective, is characterized by suffering, lack of a permanent self, and the inevitability of change. Thus, the value of life itself appears as questionable, demanding from practitioners of Buddhism the search for a deeper understanding of and consequent liberation from the cycle of suffering or saṃsāra.[16][18]: 130 Pleasure doesn't add anything positive to our experienceA number of philosophers have put forward criticisms of pleasure, essentially denying that it adds anything positive to our well-being above the neutral state. Pleasure as the mere removal of painA particular strand of criticism of pleasure goes as far back as to Plato, who said that most of the pleasures we experience are forms of relief from pain, and that the unwise confuse the neutral painless state with happiness.[39]: 286–287 Epicurus pushed this idea to its limit and claimed that, "[t]he limit of the greatness of the pleasures is the removal of everything which can give pain".[23]: 474 As such, according to Epicureans, one can not be better off than being free from pain, anxiety, distress, fear, irritation, regret, worry, etc. — in the state of tranquillity.[40][41]: 117–121 Pleasure as the mere relief from strivingSchopenhauer maintained that only pain is positive, that is, only pain is directly felt — it's experienced as something which is immediately added to our consciousness. On the other hand, pleasure is only ever negative, which means it only takes away something already present in our experience, such as a desire or discomfort. This constitutes his negativity thesis — that pleasure is only ever a relief from pain.[7][5]: 50 [27][42] Later German pessimists — Julius Bahnsen, Eduard von Hartmann, and Philipp Mainländer — held very similar views.[5]: 154, 208, 268 According to Schopenhauer, one way to remove pain is to satisfy a desire, since to strive is to suffer, so once a desire is satisfied, suffering momentarily ceases.[42] Expanding on this idea, other thinkers suggest that cravings arise when we focus on external objects or perceive something undesirable in our current situation. These cravings create a visceral need to alter the state of affairs. In contrast, the absence of such cravings leads to a state of contentment or tranquillity, characterized by a lack of urgency to change one's experience.[43][44]: 254–255 No neutral or genuine positive statesA stronger version of this view is that there may be no undisturbed states. It's at least plausible that in every state we could notice some dissatisfactory quality such as tiredness, irritation, boredom, worry, discomfort, etc. Instead of neutral states, there may simply be "default" states — states with recurrent but minor frustrations and discomforts that, over time, we got used to and learned not to do anything about.[11]: 71–73 [40][44]: 255 [45]: 23–24 Certain thinkers argue that positive experiences are conceptually and empirically difficult to establish as truly distinct or as opposites to negative experiences.[note 1] Life contains uncompensated evilsOne argument for the negative view on life is the recognition that evils are unconditionally unacceptable. A good life is not possible with evils in it. This line of thinking is based on Schopenhauer's statement that "the ill and evil in the world... even if they stood in the most just relation to each other, indeed even if they were far outweighed by the good, are nevertheless things that should absolutely never exist in any way, shape or form" in The World as Will and Representation.[47]: 181 [28]: 9–10 [27]: 283 The idea here is that no good can ever erase the experienced evils, because they are of a different quality or kind of importance.[48]: 63–64 Schopenhauer elaborates on the vital difference between the good and the bad, saying that, "it is fundamentally beside the point to argue whether there is more good or evil in the world: for the very existence of evil already decides the matter since it can never be cancelled out by any good that might exist alongside or after it, and cannot therefore be counterbalanced", and adding that, "even if thousands had lived in happiness and delight, this would never annul the anxiety and tortured death of a single person; and my present wellbeing does just as little to undo my earlier suffering."[47]: 591 [7][28]: 9–10 [27]: 283 One way of interpreting the argument is by focusing on how one thing could compensate another. The goods can only compensate the evils, when they a) happen to the same subject, and b) happen at the same time. The reason why the good has to happen to the same subject is because the miserable cannot feel the happiness of the joyful, and hence it has no effect on him. The reason why the good has to happen at the same time is because the future joy does not act backwards in time, and so it has no effect on the present state of the suffering individual. But these conditions are not being met, and hence life is not worth living. Here, it doesn't matter whether there are any genuine positive pleasures, because since pleasures and pains are experientially separated, the evils are left unrepaid.[7][27] Another interpretation of the negativity thesis — that goods are merely negative in character — uses metaphors of debt and repayment, and crime and punishment. Here, merely ceasing an evil does not count as paying it off, just like stopping committing a crime does not amount to making amends for it. The bad can only be compensated by something positively good, just like a crime has to be answered for by some punishment, or a debt has to be paid off by something valuable. If the good is merely taking away an evil, then it cannot compensate for the bad since it's not of the appropriate kind — it's not a positive thing that could "repay the debt" of the bad.[49] Suffering is essential to life because of perpetual strivingArthur Schopenhauer introduces an a priori argument for pessimism. The basis of the argument is the recognition that sentient organisms — animals — are embodied and inhabit specific niches in the environment. They struggle for their self-preservation; striving to satisfy wants is the essence of all organic life. But all striving, Schopenhauer argues, involves suffering. Thus, he concludes that suffering is unavoidable and inherent to existence. Given this, he says that the balance of good and bad is on the whole negative.[13][28]: 9–10 There are a couple of reasons why suffering is a fundamental aspect of life:[27][28]: 9–10

The asymmetry between harms and benefitsDavid Benatar, a South African philosopher at the University of Cape Town, argues that there is a significant difference between lack/presence of harms and benefits when comparing a situation when a person exists with a situation when said person never exists. The starting point of the argument is the following noncontroversial observation:[12]: 28–59 [17]: 97–126 Based on the above, Benatar infers the following:[12]: 28–59

In short, the absence of pain is good, while the absence of pleasure is not bad. From this it follows that not coming into existence has advantages over coming into existence for the one who would be affected by coming into the world. This is the cornerstone of his argument for antinatalism — the view that coming into existence is bad and hence that bringing other beings into existence is morally wrong.[12]: 28–59 [17]: 100–103 Empirical differences between the pleasures and pains in lifeTo further support his case for pessimism, Benatar mentions a series of empirical differences between the pleasures and pains in life. In a strictly temporal aspect, the most intense pleasures that can be experienced are short-lived (e.g. orgasms), whereas the most severe pains can be much more enduring, lasting for days, months, and even years.[11]: 77 The worst pains that can be experienced are also worse in quality or magnitude than the best pleasures are good, offering as an example the thought experiment of whether one would accept "an hour of the most delightful pleasures in exchange for an hour of the worst tortures".[11]: 77 In addition to citing Schopenhauer, who made a similar argument, when asking his readers to "compare the feelings of the animal that devours another with those of the one being devoured";[50]: 263 Benatar posits further challenges by wanting us to contrast the amount of time it may take for one's desires to be fulfilled, with some of our desires never being satisfied;[11]: 79 the quickness with which one's body can be injured, damaged, or fall ill, and the comparative slowness of recovery, with full recovery sometimes never being attained;[11]: 77–78 the existence of chronic pain, but the comparative non-existence of chronic pleasure;[11]: 77 the effortless way in which the bad things in life naturally come to us, and the efforts one needs to muster in order to ward them off and obtain the good things.[11]: 80 To these stark disparities, he adds points about the lack of a cosmic or transcendent meaning to human life as a whole[11]: 35–36 and the gradual and inevitable physical and mental decline to which every life is subjected through the process of ageing.[11]: 78–79 Benatar concludes that, even if one argues that the bad things in life are in some sense necessary for human beings to appreciate the good things in life, or at least to appreciate them fully, he asserts that it is not clear that this appreciation requires as much bad as there is, and that our lives are worse than they would be if the bad things were not in such sense necessary.[11]: 85

Entropy, decay and terminality Julio Cabrera, Philipp Mainländer, and Drew M. Dalton have explored the concepts of entropy, decay, and terminality in existence, particularly in the context of the collective conflict that such features embedded within life imply for living beings, as well as the eventual and ultimate obliteration of the totality of existence itself.[35][51][52][34] Structural terminality of human lifeJulio Cabrera, an Argentine philosopher living in Brazil, presents an ontology in which human life has a structurally negative value. On this view, discomfort is not provoked in humans due to the particular events that happen in the lives of individuals, but due to the very nature of human existence. He posits that human beings are inherently subject to deterioration, with their existence being in constant decay since conception. To counteract this decline and its accompanying three types of friction — physical pain, discouragement (from mild boredom to serious depression), and social aggression — human beings create positive values (aesthetic, religious, entertaining) that are fleeting and ultimately palliative, as they do not arise from the structure of life itself, but must be introduced into life with effort to lessen suffering.[35]: 23–24 [53]: 92–93 However, this pursuit of positive values gives rise to the phenomenon of moral impediment, wherein individuals inadvertently harm others in their struggle to create meaning in a decaying existence.[35]: 52–54 [53]: 93–94 The "will to death" as a drive towards cosmic annihilationPhilipp Mainländer, a 19th-century German philosopher and one of the post-Schopenhauerian pessimists, introduces the concept of the "will to death," which he posits as the fundamental metaphysical principle of existence. Mainländer asserts that the world, as a product of God's self-sacrifice[note 2], is His "rotting corpse," and that the ultimate aim or telos of everything that exists is to finally exterminate itself. In this view, the plurality and diversity of individual wills within existence, through their pursuit towards life (that is to say, their will to life), struggle against and consume each other,[34]: 233 thereby hastening God's original pursuit of non-being. According to Mainländer, the best understanding we can gain of the nature of existence is as a drive toward cosmic annihilation which has been “slowed down” through organic and living processes — life is something, in other words, that appears as a purely transitory phase in the accomplishment of the world's absolute oblivion,[34]: 232 as every living being, from plants, animals, and, finally, humans, inexorably perishes and ceases to be — no matter how intense their will to life may appear to be at a initial and superficial glance[52]: 394 "The whole universe," he writes in summation, “moves from being to non-being, continually weakening its power, [and therefore] has an end: it is not endless, but leads to a pure absolute nothingness — to a nihil negativum."[34]: 231 Mainländer's scientific pessimism builds on the foundations laid by Schopenhauer, yet he diverges from them by emphasizing that a "true philosophy" must be grounded in immanent or empirical reality, thus rejecting any appeal to transcendent or spiritual realms (such as Schopenhauer's view that there is one unifying Will in reality, which, being the thing-in-itself, is the timeless, undifferentiated, and acausal principle of being). He argues that the natural sciences provide the best foundation for understanding existence, revealing that the totality of reality is in fact composed of diverse individual wills, each striving to live while simultaneously and ultimately contributing to the demise and decay of others.[34]: 228–233 The "unbecoming" of the world through entropic decayDrew M. Dalton, an American philosopher and a professor of English at Indiana University, expands on these themes by grounding them in contemporary scientific understanding, particularly through the lens of entropy as outlined in the second law of thermodynamics and the contemporary mathematical sciences.[54] He argues that the universe is characterized by entropic decay, where all matter and energy are in a constant state of dissipation, and being itself is in a process of "unbecoming".[55] Dalton posits that everything that exists is not only destined to disintegrate but is also actively working toward this end. He describes existence as an "annihilative machine," where every being contributes to its own destruction and the destruction of others — and, indeed, to the destruction of being itself (that is to say, the destruction of everything that is living or non-living, organic or inorganic). This entropic nature of reality implies that existence is fundamentally antagonistic to itself, requiring beings to maintain themselves at the expense of others within a "metaphysics of decay".[34]: 275–278 Valuelessness of mere existence Blaise Pascal, Arthur Schopenhauer and Julio Cabrera sustain that mere existence itself lacks intrinsic value.[35][56][50]: §146 Cabrera argues that all pleasure derives from external "estantes" (contingent supports or distractions found within the world) rather than from being itself. He illustrates this through the experience of solitary confinement, where a prisoner, stripped of all distractions, is left completely alone with their pure being. This state reveals the profound suffering associated with bare existence; if being were inherently valuable, such isolation would not constitute a severe form of torture. Instead, the overwhelming pain and despair experienced in such an extreme form of solitude underscores the notion that humans constantly require external values and diversions to find meaning in life.[35]: 146 [53]: 93 Cabrera further contends that life is often viewed as a means to an end rather than an end in itself. Moral philosophers recognize that mere survival, devoid of purpose or fulfillment, is often seen as a miserable way of living. This perspective suggests an inherent understanding that being itself does not confer positive value; rather, it is a possible engagement with the world that may imbue life with meaning. The torturous conditions of confinement, where individuals are left with nothing but their mere existence, exemplify this lack of intrinsic worth.[57]: 46–47 Schopenhauer echoes these sentiments, asserting that if existence held any positive value in itself, boredom would simply not exist; mere being would suffice for us and we should have no need for anything else. Instead, humans find fleeting satisfaction only through striving for goals or engaging in intellectual or artistic pursuits, which momentarily distract them from the inherent vacuity of existence. When, however, confronted with the reality of sheer existence, the emptiness of life becomes painfully apparent.[50]: §146 Blaise Pascal, a French philosopher from the XVII century, also addresses this theme of diversion, suggesting that humans engage in various distractions to avoid confronting the deeper questions of existence and the suffering that accompanies self-awareness. In his work "Pensées," Pascal argues that people often seek entertainment and social interaction as a means to escape the anxiety and existential dread that arise from an awareness of their finitude.[58]: 199 He encapsulates this idea in a famous maxim: "All the unhappiness of men arises from one single fact, that they cannot stay quietly in their own chamber."[56] Meaninglessness of lifeDavid Benatar acknowledges that while we can derive meaning from terrestrial perspectives — through acts of kindness, creativity, and societal contributions — these meanings are terrestrially limited and do not confer cosmic significance. He emphasizes that sentient life as a whole is irredeemably senseless from a cosmic perspective, with our existences having no impact whatsoever on the broader universe. The evolution of life, including human life, is a product of blind physical and chemical forces and serves no apparent purpose.[11]: 35–36 Similarly, Peter Wessel Zapffe, a Nowergian philosopher from the 20th century, articulates a profound sense of existential despair rooted in the nature of human interests and the limitations of our earthly existence. In his work On the Tragic, Zapffe categorizes human interests into four types: biological, social, autotelic, and metaphysical. While biological and social interests pertain to survival and relationships, it is the metaphysical interests— our yearning for justice and meaning — that Zapffe considers most significant. He argues that while we may find temporary satisfaction in autotelic pursuits, these do not provide a sufficient foundation for life's overarching meaning. Ultimately, he concludes that life is meaningless because it cannot be externally justified, as our earthly environment fails to fulfill our metaphysical interests (in other words, life lacks a heterotelic source of meaning and justice, which are outside of life itself and thus independent of humans' efforts). The consciousness of death further underscores this futility, revealing the transient nature of our endeavors and stripping life of enduring significance.[59][32]: 59–60 Responses to the evils of existencePessimistic philosophers came up with a variety of ways of dealing with the suffering and misery of life. The Noble Eightfold PathBuddhism addresses the evils of existence through the framework of the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path. The Four Noble Truths articulate the nature of suffering (dukkha), its origin in desire and attachment, the possibility of cessation (nirvana), and the path leading to this cessation. The Noble Eightfold Path provides practical guidance for ethical and mental development, emphasizing right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. By following this path, individuals can cultivate wisdom and compassion, ultimately mitigating suffering and achieving a state of inner peace.[60]: 11 Schopenhauer's renunciation of the will to lifeArthur Schopenhauer regarded his philosophy not only as a condemnation of existence, but also as a doctrine of salvation that allows one to counteract the suffering that comes from the will to life and attain tranquillity.[5]: 52 According to Schopenhauer, suffering comes from willing (striving, desiring). One's willing is proportional to one's focus on oneself, one's needs, fears, individuality, etc. So, Schopenhauer reasons, to interrupt suffering, one has to interrupt willing. And to diminish willing, one has to diminish the focus on oneself. This can be accomplished in a couple of ways.[29][4]: 107–108 [3]: 375–376 [61]: 335–341 Aesthetic contemplationAccording to Schopenhauer, aesthetic contemplation means the focused appreciation of a piece of art, music, or even an idea, with such contemplation being both disinterested and impersonal. It is disinterested — one's interests give way to a devotion to the object; the object is considered as an end in itself. And it is also impersonal — not constrained by one's own likes and dislikes. Aesthetic appreciation evokes a universal idea of an object, rather than the perception of the object as unique.[29][5]: 60–61 [4]: 108–110 During that time, for Schopenhauer, one "loses oneself" in the object of contemplation, and the sense of individuation temporarily dissolves. This is because the universality of the object of contemplation passes onto the subject. One's consciousness becomes will-less. One becomes — if only for a brief moment — a neutral spectator or a "pure subject", unencumbered by one's own self, needs, and suffering.[29][5]: 60–61 [4]: 108–110 Similarly, Schopenhauer argued that one way to get rid of suffering is to distract oneself from it. When we're not paying attention to what we lack — and hence, desire — we are temporarily at peace.[42] Compassionate moral outlookFor Schopenhauer, a proper moral attitude towards others comes from the recognition that the separation between living beings occurs only in the realm of representation, originating from the principium individuationis. Underneath the representational realm, we are all one. Each person is, in fact, the same Will — only manifested through different objectifications. The suffering of another being is thus our own suffering.[62]: 380–381 The recognition of this metaphysical truth allows one to attain a more universal, rather than individualistic, consciousness. In such a universal consciousness, one relinquishes one's exclusive focus on one's own well-being and woe towards that of all other beings.[62]: 405 [29] AsceticismSchopenhauer explains that one may go through a transformative experience in which one recognizes that the perception of the world as being constituted of separate things, that are impermanent and constantly striving, is illusory. This can come about through knowledge of the workings of the world or through an experience of extreme suffering.[3]: 376–377 One sees through the veil of Maya. This means that one no longer identifies oneself as a separate individual. Rather, one recognizes himself as all things. One sees the source of all misery — the Will as the thing-in-itself, which is the kernel of all reality. One can then change one's attitude to life towards that of the renunciation of the will to life and practice self-denial (not giving in to desires).[62]: 405–407 For Schopenhauer, the person who attains this state of mind lives their life in complete peace and equanimity. They are not bothered by desires or lack; they accept everything as it is. This path of redemption, Schopenhauer argues, is more permanent, since it's grounded in a profound recognition that changes one's attitude; it's not merely a fleeting moment as in the case of an aesthetic experience.[5]: 61 However, the ascetic way of life, according to him, is not available for everyone — only a few rare and heroic individuals may be able to live as ascetics and attain such a state. More importantly, Schopenhauer explains that asceticism requires virtue; and virtue can be cultivated but not taught.[29][5]: 61–62 [3]: 375–379 Humor and laughter In his 1877 work "Das Tragische als Weltgesetz und der Humor als ästhetische Gestalt des Metaphysischen" (The Tragical as World Law and Humor as Aesthetic Shape of the Metaphysical), Julius Bahnsen, a 19th-century German philosopher as well as another of the post-Schopenhauerian pessimists, argues that tragedy is an inherent part of human existence — arising from the conflict between incommensurable moral values and duties.[5]: 264 For Bahnsen, the essence of tragedy lies in the recognition that the moral dilemmas of life do not contain within themselves clear or consistent solutions; that every action carries the weight of competing values and opposing conceptions of the good life, thus resulting in unavoidable moral transgressions. This, for Bahnsen, makes is so that — differing from Schopenhauer, von Hartmann and even Mainländer — there is no redemption from the tragedy of life; not through asceticism, aesthetic contemplation or even suicide. Due to our obligations and commitments towards others and to our communities as a whole, we cannot escape into another world or annihilate ourselves — we are thus inextricably caught within "the drama of the world".[5]: 267 Bahnsen, however, puts forward the idea that, despite there being no redemption or salvation from the moral tragedies inherent to life, there is something we can do to alleviate the burden of existence, which for him is humor and laughter. While they allow us to recognize our powerlessness towards our predicament, humor and laughter also permit us to stand above the moral impasses pressing down on us by momentarily abstracting ourselves from them.[5]: 267 Philipp Mainländer's political activismPhilipp Mainländer critiques the moral quietism in Schopenhauer's philosophy and early Buddhism, arguing that while these systems alleviate individual suffering, they neglect broader societal injustices. He contends that such quietisms perpetuate inequality by not empowering those who lack the means for personal moral development. For Mainländer, a truly pessimistic ethics requires both personal goodness and a commitment to social justice — ensuring that everyone has access to the education and resources necessary to recognize the lack of value of life.[34]: 237–238 To address these inequalities, Mainländer advocates for dismantling the social and political structures that sustain them, viewing the pursuit of social and political equality as an extension of compassion that arises from the recognition of existence as fundamentally evil. He supports communism and a "free love movement" (freie Liebe) as essential for a just society — promoting communal ownership and a collective responsibility to renounce the will to life.[34]: 239–241 Through such a free love movement, Mainländer seeks to redefine sexual and marital relations, liberating individuals from societal constraints which bind them to marriage and procreation, thus allowing them to pursue the path of contemplation, compassion, chastity, and finally the renunciation of being itself through suicide.[34]: 241 He sees suicide not as action originating from a sense of despair, but as a rational choice that can fully and quickly abolish one's suffering when approached with a clear understanding of the nature of existence.[34]: 236 For Mainländer, communism is the means to achieve social and economic equality which would eliminate class distinctions and ensure equal access to education and resources for all. In a communist society, individuals would transcend selfish survival instincts, fostering compassion and collective efforts to alleviate suffering.[34]: 235–243 Ultimately, Mainländer sees this communist state as the penultimate step of the will to death's metanarrative, where the satiation of all human desires will lead them to an understanding of the vanity and emptiness of existence (specifically, that the pleasures this satiation brings does not outweigh the negative value of existence), thus initiating a movement towards humanity's own extinction — aligning with the natural movement of all matter in the universe toward nothingness.[63]: 115–116 [18]: 34–35 [5]: 228 Von Hartmann's collective ending of all lifeEduard von Hartmann, much like Philipp Mainländer (one of his pessimist 19th-century German contemporaries) was also against all individualistic forms of the abolition of suffering, prominent in Buddhism and in Schopenhauer's philosophy, arguing that these approaches fail to address the problem of continued suffering for others. Instead, he opted for a collective solution: he believed that life progresses towards greater rationality — culminating in humankind — and that as humans became more educated and more intelligent, they would see through various illusions regarding the abolition of suffering, eventually realizing that the problem lies ultimately in existence itself.[17]: 81–83 [5]: 126–161 [64][65] Thus, humanity as a whole would recognize that the only way to end the suffering present in life is to end life itself. This would happen in the future, where people would have advanced technologically to a point where they could destroy the whole of nature. That, for von Hartmann, would be the ultimate negation of the Will by Reason.[17]: 81–83 [5]: 126–161 [64][65] Amor fati and eternal recurrenceFriedrich Nietzsche, a 19th-century German philosopher, advocated an unmitigated acceptance of existence through the concepts of amor fati and eternal recurrence. Amor fati, or "love of (one's) fate," encourages individuals to embrace their life experiences, including suffering and hardship, as essential components of their existence. Nietzsche posits that by affirming life in its entirety, one can transcend nihilism and find meaning even in adversity. The idea of eternal recurrence further encourages individuals to live as if they would have to relive their lives repeatedly, prompting a deep appreciation for each moment and a commitment to living authentically.[4]: 191 In his 1942 essay The Myth of Sisyphus, the 20th century French philosopher Albert Camus similarly presents a kind of "heroic pessimism"; that is to say, a perspective that resonates with Nietzsche's affirmation of life, particularly in the face of existential absurdity. While Nietzsche advocates for an unqualified acceptance of existence through the concepts of amor fati and eternal recurrence, Camus on the other hand makes use of Sisyphus's punishment as a metaphor for the human condition, similarly emphasizing the importance of embracing life, even amidst its inherent struggles and absurdities.[18]: 181 Zapffe's defence mechanismsPeter Wessel Zapffe viewed humans as animals with an overly developed consciousness who yearn for justice and meaning in a fundamentally meaningless and unjust universe — constantly struggling against feelings of existential dread as well as the knowledge of their own mortality. He identified four defence mechanisms that allow people to cope with disturbing thoughts about the nature of human existence:[31][17]: 91–94 Isolation: the troublesome facts of existence are simply repressed — they are not spoken about in public, and are not even thought about in private.[31] Anchoring: one fixates (anchors) oneself on cultural projects, religious beliefs, ideologies, etc.; and pursue goals appropriate to the objects of one's fixation. By dedicating oneself to a cause, one focuses one's attention on a specific value or ideal, thus achieving a communal or cultural sense of stability and safety from unsettling existential musings.[31] Distraction: through entertainment, career, status, etc., one distracts oneself from existentially disturbing thoughts. By constantly chasing for new pleasures, new goals, and new things to do, one is able to evade a direct confrontation against mankind's vulnerable and ill-fated situation in the cosmos.[31] Sublimation: artistic expression may act as a temporary means of respite from feelings of existential angst by transforming them into works of art that can be aesthetically appreciated from a distance.[31] Terror Management TheoryTerror management theory (TMT) postulates that awareness of mortality leads to existential fear, which individuals manage through cultural beliefs and ideologies. Rooted in Ernest Becker's The Denial of Death, TMT builds on his argument that the fear of death is a fundamental human concern driving much of our behavior. Becker posits that people deny their mortality by embracing cultural narratives and ideologies that imbue their lives with meaning and a sense of permanence. When faced with death's inevitability, individuals adopt symbolic worldviews — such as cultural, religious, or personal ideologies — to repress existential angst.[66][67] Thomas Ligotti, an American horror writer, draws parallels between TMT and Zapffe's philosophy, noting that both recognize humans' heightened self-awareness of mortality and the coping mechanisms this awareness necessitates. Zapffe argues that people shield themselves from existential despair by limiting consciousness, engaging in distractions, and constructing artificial meaning — a view that echoes Becker's analysis of how individuals use social and psychological strategies to manage their fear of death.[18]: 158–159 Biomedical enhancementPeter Wessel Zapffe was skeptical of many forms of technological enhancements, viewing them primarily as superficial distractions that fail to address the deeper existential questions present in human life. He argued that while technology can meet basic biological needs, it does not resolve the inherent suffering and anxiety that characterize the human condition. From Zapffe's perspective, the current human baseline is itself in a "sick" state due to our overly developed awareness towards questions regarding metaphysical meaning and justice within existence, which challenges the traditional distinction between health and enhancement.[68]: 322 However, Zapffe does concede that biotechnology could, at least in theory, alter our metaphysical needs, and thus not be merely a tool for distraction. Moen argues that Zapffe's view therefore suggests that both extinction and successful enhancement would be preferable to the continuation of the current state of human existence, thereby strengthening the argument for pursuing biomedical enhancements, particularly those aimed at improving human welfare.[68]: 322 Zapffe also points out that, due to our intellect as humans, we are able to comprehend the "the brotherhood of suffering between everything alive".[68]: 316 In a related vein, British philosopher David Pearce advocates for the application of biomedical enhancement not only to humans but also to non-human animals. Pearce argues that a long-term goal should be to redesign ecosystems and rewrite the vertebrate genome to eliminate suffering across all sentient beings. He posits that advancements in technology could eventually enable humanity to significantly reduce suffering in nature, thereby addressing the broader ethical implications of suffering beyond human existence.[68]: 323–325 Antinatalism and extinctionConcern for those who will be coming into this world has been present throughout the history of pessimism. Notably, Arthur Schopenhauer asked:[50]: 318–319

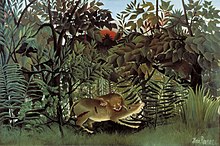

Schopenhauer also compares life to a debt that's being collected through urgent needs and torturing wants. We live by paying off the interests on this debt by constantly satisfying the desires of life; and the entirety of such debt is contracted in procreation: when we come into the world.[47]: 595 Anthropocentric antinatalismSome pessimists prescribe abstention from procreation as the best response to the ills of life. A person can only do so much to secure oneself from suffering or help others in need. The best course of action, they argue, is to not bring others into a world where discomfort is guaranteed.[12][35][17]: 90–126 Additionally, some of them take into consideration a scenario where humanity decides not to continue to exist, but instead chooses to go down the route of phased extinction. The resulting extinction of the human species would not be regrettable but a good thing.[12]: 163–200 They go as far as to prescribe non-procreation as the morally right — or even obligatory — course of action.[11]: 207–208 [17]: 90–126 Zapffe conveys this position through the words of the titular Last Messiah: "Know yourselves – be infertile and let the earth be silent after ye".[31] Sentiocentric antinatalismAntinatalism can be extended to non-human animals. Benatar asserts that his argument for antinatalism "applies not only to humans but also to all other sentient beings" and that "coming into existence harms all sentient beings".[12]: 2 He reinforces his view when discussing extinction by saying "it would be better, all things considered, if there were no more people (and indeed no more conscious life)."[12]: 164 It can be argued that since we have a prima facie obligation to help humans in need, and preventing future humans from coming into existence is helping them, and there is no justification for treating animals worse, we have a similar obligation to animals living in the wild. That is, we should also help alleviate their suffering and introduce certain interventions to prevent them from coming into the world — a position which would be called "wildlife anti-natalism".[69][70] Julio Cabrera recognizes that non-human animals go through a lot of suffering throughout their life, but because they are not failing as moral beings (as they are not moral beings to begin with), there is no "procreation problem" or reason to adopt an antinatalist stance toward them.[71]: 584–604 Suicide Some pessimists, including David Benatar, Philipp Mainländer and Julio Cabrera, argue that in some extreme situations, such as intense pain, terror, and slavery, people are morally justified to end their own lives. Although this will not resolve the human predicament, it may at the very least stop further suffering or moral degradation of the person in question.[35]: 246–249 [11]: 163–199 [34]: 235–243 [72] Cabrera says that dying is usually not pleasant nor dignified, so suicide is the only way to choose the way one dies. He writes, "If you want to die well, you must be the artist of your own death; nobody can replace you in that."[35]: 249 Arthur Schopenhauer rejects various objections to suicide stemming from religion, as well as those based on accusations of cowardice or insanity regarding the person who decides to end their own life. In this perspective, we should be compassionate towards the suicide — we should understand that someone may not be able to bear the sufferings present in their own life, and that one's own life is something that one has an indisputable right to.[50]: §157 Schopenhauer, however, does not see suicide as a kind of solution to the sufferings of existence. His opposition to suicide is rooted in his metaphysical system. Schopenhauer focuses on human nature — which is governed by the Will. This means that we are in a never ending cycle of striving to achieve our ends, feeling dissatisfied, feeling bored, and once again desiring something else. Yet because the Will is the inner essence of existence, the source of our suffering is not exactly in us, but in the world itself.[62]: 472 For Schopenhauer, taking one's life is a mistake, for one still would like to live, but simply in better conditions. The suicidal person still desires goods in life — a "person who commits suicide stops living precisely because he cannot stop willing".[62]: 472 It is not one's own individual life that is the source of one's suffering, but the Will, the ceaselessly striving nature of existence. The mistake is in annihilating an individual life, and not the Will itself. The Will cannot be negated by ending one's life, so it's not a solution to the sufferings embedded in existence itself.[62][47][72][17]: 63–65 David Benatar considers many objections against suicide, such as it being a violation of the sanctity of human life, a violation of the person's right to life, being unnatural, or being a cowardly act, to be unconvincing. The only relevant considerations that should be taken into account in the matter of suicide are those regarding people to whom we hold some special obligations. Such as, for example, our family members. In general, for Benatar the question of suicide is more a question of dealing with the particular miseries of one's life, rather than a moral problem per se. Consequently, he argues that, in certain situations, suicide is not only morally justified but is also a rational course of action.[11][72] Benatar's arguments regarding the poor quality of human life do not lead him to the conclusion that death is generally preferable to the continuation of life. But they do serve to clarify why there are cases in which one's continued existence would be worse than death, as they make it explicit that suicide is justified in a greater variety of situations than we would normally grant. Every person's situation is different, and the question of the rationality of suicide must be considered from the perspective of each particular individual — based on their own hardships and prospects regarding the future.[12][73][72] Jiwoon Hwang argued that the hedonistic interpretation of David Benatar's axiological asymmetry of harms and benefits entails promortalism — the view that it is always preferable to cease to exist than to continue to live. Hwang argues that the absence of pleasure is not bad in the following cases: for the one who never exists, for the one who exists, and for the one who ceased to exist. By "bad" we mean that it's not worse than the presence of pleasure for the one who exists. This is consistent with Benatar's statement that the presence of pleasure for the existing person is not an advantage over the absence of pleasure for the never existing and vice versa.[74] Pessimism and other philosophical topicsAnimals Aside from the human predicament, many philosophical pessimists also emphasize the negative quality of the life of non-human animals and sentient existence as a whole, thereby criticizing the notion of nature as a "wise and benevolent" creator.[11]: 42–44 [47]: 364–376 [75] Some philosophers refer to an often-cited evolutionary biologist, Richard Dawkins, who made explicit remarks regarding the immensity of senseless suffering in the animal kingdom, summing it up as being "beyond all decent contemplation",[76]: 131–132 [77] and to one of the creators of the theory of evolution by natural selection, Charles Darwin, who rejected the idea of a benevolent God on the account of suffering of animals who don't get any moral improvements out of it.[78][79]: 90 [3]: 8–9 Some academics provide an argument for "evolutionary pessimism": considering the immense amount of suffering (including physical pain, emotional distress, predation, parasitism, aggression, starvation, and disease) that has been going on for hundreds of millions of years throughout evolutionary history, it's plausible that the cumulative negative value suffered by sentient beings far outweighs the positive value experienced by them. A substantial amount of goods would have to come about in the future to balance out the evils. The future goods are not certain and they may never make up for the "evolutionary evil", so the argument concludes that it's likely that it would have been better if evolution had not given rise to sentient beings at all.[77] Thinkers involved in the field of wild animal suffering point out that suffering in nature is pervasive among many animal species. These creatures often produce numerous offspring who frequently die young, often through painful means such as disease, predation, or harsh environmental conditions. Due to their short lifespans, they have limited opportunities for positive experiences while being disproportionately exposed to negative ones. Additionally, researchers suggest that many of these animals are already sentient at birth, meaning they can experience suffering immediately upon entering the world. These scholars thus argue that suffering outweighs pleasure in wild animals.[80][81][82][83] Giacomo LeopardiIn his "Dialogue Between Nature and an Icelander", the Italian philosopher and poet Leopardi, through the voice of the titular Icelandic character in the dialogue, expresses deep concern over the immense suffering experienced by wild animals. He argues that Nature is inherently cruel, with animals constantly preying on and devouring one another in a relentless struggle for survival. The Icelandic character laments the "wretched life of the world" and "the suffering and death of all the beings which compose it", with no respite or escape from such universal torment.[84]: 79 [75] Leopardi, through this character, rejects the idea that nature is benevolent or that wild animals live in a state of happiness and contentment. Instead, he portrays Nature as indifferent to the plight of its creatures, driven solely by the merciless laws of competition and the survival of the fittest. The Icelandic character pleads with Nature to show compassion and alleviate the suffering of both humans and wild animals — but Nature remains unmoved, defending its cruel ways as a necessary part of the natural order. The core of his pessimism lies in his rejection of the necessity of predation in life and the rejection of the value of the cycle of destruction and regeneration.[84][75] Arthur SchopenhauerSchopenhauer's philosophical pessimism also extended to his views on animals.[6]: 36 He believed that animals, like humans, are subject to the metaphysical Will and therefore also experience suffering and craving. As a result, he argued that animals should be treated with respect and compassion, and that their rights should be recognized. Schopenhauer criticized traditional Christian views on animals, which he saw as immoral and based on a flawed assumption of human superiority.[85]: §8 [75] Instead, he cherished universal compassion that recognizes the inherent value of all living beings and is the motive for good and just actions.[85]: §19 Still, he believed that humans need to eat animals for sustenance[62]: 178–179 and because the capacity to suffer is linked with intelligence (and, for him, humans are much more intelligent than animals as they are the Will's highest form of manifestation or objecthood),[62]: 151 [10]: 95 people are justified in eating animals as they would suffer more by not eating animals than animals would by being killed.[62]: 399–400 [85]: 231 Eduard von HartmannVon Hartmann echoed a perspective similar to British philosopher Jeremy Bentham's from a century earlier: since all animals inevitably face death, taking an animal's life in a manner that is quicker and less painful than what it would endure naturally should not be considered morally objectionable.[86] Julio CabreraJulio Cabrera argues that while humans are subjected to a triad of suffering — pain, discouragement, and moral impediment — non-human animals experience only a dyad: pain and discouragement, but not moral impediment. This is because they lack the capacity to be considered moral beings and therefore cannot fail morally. He suggests that this absence of a moral dimension might actually constitute a form of happiness for non-human animals, as it spares them one of the existential burdens humans face. As a result, their lives are not structurally disvalued in the same way as human lives. At the same time, he acknowledges that non-human animals still endure harsh conditions and significant suffering in the wild, further exacerbated by human actions.[71]: 584–604 Cabrera further argues that since animals are not moral beings, humans cannot enter into ethical relations with them, meaning we cannot hold moral duties toward animals or ascribe rights to them. However, while he argues that we cannot enter into contracts with non-human animals due to the absence of reciprocity, symmetry, and a moral dimension, this does not justify mistreatment of them. Instead, one might contend that focusing on their well-being rather than on formal ethical agreements, constitutes an ethical decision in itself—potentially the only viable approach we can take with animals (who lack a moral dimension).[71]: 584–604 MisanthropyMisanthropy is closely related to but not identical with philosophical pessimism; while pessimism emphasizes the inherent suffering of life, misanthropy critiques humanity's moral failings. A philosophical pessimist may argue that the suffering of existence is universal and unavoidable, while a misanthrope may focus on how human actions exacerbate this suffering through cruelty, indifference, and moral corruption. Thus, while both perspectives share a critical view of humanity, they diverge in their focus: pessimism on the nature of existence itself, and misanthropy on humanity's role within that existence.[87] Philosophical pessimism can lead to misanthropy if one concludes that human nature is a significant contributor to the suffering and futility of existence. Conversely, a misanthropic perspective might reinforce a pessimistic worldview, as negative experiences with humanity can lead to broader existential anguish.[88]: 5–6 AbortionEven though pessimists agree on the judgment that life is bad and some pessimistic antinatalists criticise procreation, their views on abortion differ.[12]: 133–162 [35]: 208–233 Pro-death viewDavid Benatar holds a "pro-death" stance on abortion. He argues that in the earlier stages of pregnancy, when the fetus has not yet developed consciousness and has no morally relevant interests, we should adopt a presumption against carrying the fetus to term. What demands justification is not the act of abortion, but the failure to abort the fetus (in the early stages of pregnancy). Benatar does not argue that such early abortions should be mandatory, but only that it would be preferable to perform the abortion.[12]: 133–162 Anti-abortion viewJulio Cabrera notices that abortion requires consideration of and action upon something that is already there. He argues that we must take it into our moral deliberations, regardless of the nature of that thing.[35]: 209–210 Cabrera argues against abortion from the standpoint of negative ethics. He begins by suggesting that it's wrong to eliminate another human being purely for our own benefit, as this treats the person as a mere obstacle to be removed. He also highlights the importance of protecting those who can't defend themselves, and within the context of gestation, pregnancy, and birth, the fetus is the most helpless and vulnerable being involved. Moreover, in his view, a fetus is a being who starts to terminate as a human being. For these reasons, Cabrera concludes that it is morally wrong to terminate (abort) a human being.[35]: 210 Cabrera further elaborates on the argument with a couple of points. Since we are all valueless, the victimizer has no greater value than the victim to justify the killing. It's better to err on the side of caution and not abort because it's difficult to say when a fetus becomes a human. A fetus has a potential to become a rational agent with consciousness, feelings, preferences, thoughts, etc. We can think of humans as beings who are always in self-construction; and a fetus is such a type of being. Furthermore, a fetus is — like any other human being — in a process of "decay". Finally, we should also debate the status of those who perform abortions and the women who undergo abortions; not just the status of the fetus.[35]: 211–219 DeathFor Arthur Schopenhauer, every action (eating, sleeping, breathing, etc.) was a struggle against death, although one which always ends with death's triumph over the individual.[62]: 338 Since other animals also fear death, the fear of death is not rational, but more akin to an instinct or a drive, which he called the will to life. In the end, however, death dissolves the individual and, with it, all fears, pains, and desires. Schopenhauer views death as a "great opportunity not to be I any longer".[47]: 524 Our inner essence is not destroyed though — since we are a manifestation of the universal Will.[89] David Benatar has not only a negative view on coming into existence, but also on ceasing to exist. Even though it is a harm for us to come into existence, once we do exist we have an interest in continuing to exist. We have plans for the future; we want to achieve our goals; there may be some future goods we could benefit from, if we continue to exist. But death annihilates us; in this way robbing us from our future and the possibility of us realizing our plans.[12][11][72] CriticismPlümacher's criticisms of SchopenhauerSwiss-American philosopher Olga Plümacher criticizes Schopenhauer's system on a variety of points. According to Schopenhauer, an individual person is itself a manifestation of the Will. But if that is the case, then the negation of the Will is also an illusion, since if it were genuine, it would bring about the end of the world. Furthermore, she notices that for Schopenhauer, the non-existence of the world is preferable to its existence. However, this is not an absolute statement (that is, it says that the world is the worst), but a comparative statement (that is, it says that it's worse than something else).[2] Sully's criticisms of philosophical pessimismJames Sully offers a psychological reduction of pessimistic beliefs, emphasizing the interplay between internal dispositions and external impressions. He argues that the emotional state of "Weltschmerz"— a pervasive sadness about existence — is not merely a philosophical stance but is deeply influenced by individual psychological traits and socioeconomic conditions.[90] He identifies several psychological traits that contribute to a pessimistic outlook, including acute sensibility, which leads to an excessive anticipation of suffering; an irritable and rebellious mindset that perceives the world as hostile; a sluggish temperament that fosters a burdensome view of life; a carping disposition that highlights the world's deficiencies compared to personal ideals; and a desire for adulation, which reinforces pessimistic beliefs by seeking recognition as a martyr for enduring suffering.[90] Sully's view resonates with the perspectives of other critics of pessimism, such as Bertrand Russell and Bryan Magee, who also contend that pessimism is not a philosophical stance but rather an emotional one. Russell characterized pessimism as a matter of temperament rather than reason,[91]: 758 while Magee suggested that Schopenhauer's despairing worldview could be seen as neurotic manifestations rooted in his relationship with his mother rather than a coherent philosophical argument.[24]: 13 By framing pessimism as a response to emotional and environmental factors, Sully challenges the rationality and coherence of philosophical pessimism, suggesting that such beliefs may be more reflective of individual psychology and societal conditions than of objective truths about existence.[90] Nietzsche's criticisms of SchopenhauerAlthough Nietzsche acknowledged Schopenhauer's influence on his early thought, he diverged from his mentor's conclusions, ultimately seeking a life-affirming philosophy.[92]: 145 Schopenhauer posits that life is fundamentally characterized by suffering, driven by the "will to life," which he views as a blind, insatiable force that leads to endless desire and dissatisfaction. In contrast, Nietzsche introduces the concept of the "will to power," which he sees as the fundamental driving force in human beings, emphasizing the transcendence and perfection of oneself rather than mere survival. While Schopenhauer's perspective leads to an ascetic resignation and denial towards life, Nietzsche — while still subscribing to a pessimistic perspective towards life — challenges Schopenhauer's outlook (which he sees as a manifestation of "weakness") by advocating for the affirmation of life within a context where existence is not evaluated merely through hedonistic standards, but by standards based on the feelings of power that arise from the overcoming of difficulty, pain and suffering.[93]: 248 [94]: 123 Against the claim that pleasures are only ever negativeA claim pessimists often make is that pleasures are negative in nature — they are mere satisfactions of desires or removals of pains. Some object to this by providing intuitive counterexamples, where we are engaged in something pleasurable which seems to be adding some genuine pleasure above the neutral state of undisturbness.[40] This objection can be presented like this:[41]: 122

The objection here is that we can clearly introspect that we feel something added to our experience, not that we merely no longer feel some pain, boredom, or desire. Such experiences include pleasant surprises, waking up in a good mood, savoring delicious meals, anticipating something good that will likely happen to us, and others.[40][7] The response to these objections from counterexamples can run as follows. Usually, we do not focus enough on our present state to notice all disturbances (discontentment). It's likely we could notice some disturbances had we paid enough attention — even in situations where we think we experience genuine pleasure. Thus, it's at least plausible that these seemingly positive states have various imperfections, and we are not, in fact, undisturbed; and, therefore, we are below the hedonic neutral state.[40] Influence outside philosophyThe character of Rust Cohle in the first season of the television series True Detective is noted for expressing a philosophically pessimistic worldview;[95][96] the creator of the series was inspired by the works of Thomas Ligotti, Emil Cioran, Eugene Thacker and David Benatar when creating the character.[97] There is a list of pessimistic literature, which contains fiction books with pessimistic motifs. See also

ReferencesNotes

Citations

Further readingPrimary literatureBooks

Essays

Secondary literatureBooks

External linksLook up pessimism in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Wikiquote has quotations related to Philosophical pessimism.

|