|

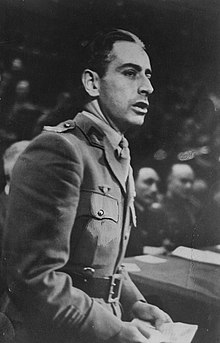

Pierre Brossolette

Pierre Brossolette (French: [pjɛʁ bʁɔsɔlɛt]; 25 June 1903 – 22 March 1944) was a French journalist, politician and major hero of the French Resistance in World War II. Brossolette ran a Resistance intelligence hub from a Parisian bookshop on the Rue de la Pompe, before serving as a liaison officer in London, where he also was a radio anchor for the BBC, and carried out three clandestine missions in France. Arrested in Brittany as he was trying to reach the UK on a mission back from France alongside Émile Bollaert, Brossolette was taken into custody by the Sicherheitsdienst (the security service of the SS). He committed suicide by jumping out of a window at their headquarters on 84 Avenue Foch in Paris as he feared he would reveal the lengths of French Resistance networks under torture; he died of his wounds later that day at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital. On 27 May 2015, his ashes were transferred to the Panthéon with national honours at the request of President François Hollande, alongside politician Jean Zay and fellow Resistance members Germaine Tillion and Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz. BiographyEducation and journalismPierre Brossolette was born in the 16th arrondissement of Paris to a family deeply involved in the fights for laic schools in early 20th century France. His father was Léon Brossolette, General Inspector for Primary Education; his mother Jeanne Vial was the daughter of Francisque Vial, Director of Secondary Education, responsible for making secondary education free in France. Brossolette ranked first at the entrance examination to the prestigious École Normale Supérieure; throughout his education held the title of "cacique" which was internally attributed to the most brilliant student, ahead of intellectuals such as philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch and two years before Jean-Paul Sartre and Raymond Aron. In 1925 he graduated second to Georges Bidault after a small scandal on the dissertation themes for the final examination. His passion for history had led him to choose this "agrégation" instead of the more usual and prestigious philosophy one. During this time and while he was in his military service, he married Gilberte Bruel and had two children, Anne and Claude. Instead of pursuing an academic career like most normaliens, he longed for action and decided to enter journalism and politics. He joined the Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière (SFIO), the main socialist party, in 1929, adhered to the LDH and LICA league and entered freemasonry. He worked as a journalist for Notre Temps, L'Europe Nouvelle, the party newspaper Le Populaire and the state-owned Radio PTT but was fired when he violently opposed the Munich Agreement on air in 1939. In his newspaper columns, Brossolette had evolved from a resolute pacifist and europeanist, after Aristide Briand's ideals, to a denunciator of both fascism and communism. Resistance activitiesWhen World War II broke out, he joined the army as a lieutenant of the 5th régiment d'infanterie; before the fall of France, he reached the rank of captain receiving two citations for the French War Cross for having retreated his battalion in an orderly way. After the Armistice, when the Vichy regime forbade him to teach, Brossolette and his wife took over a bookstore specialised in Russian literature at the Rue de la Pompe near Lycée Janson-de-Sailly, where he had attended high school. The bookstore became an intelligence hub of Parisian resistance where documents, such as Renault factory plans used for its bombing, were exchanged unnoticed, thanks to the extensive library available underground. He was a popular voice on the radio before the war and his chronicles on Hitler's rise led to being blacklisted early in the 1930s by the Nazis. It did not take long before he was approached by his friend Agnès Humbert and introduced to Jean Cassou and the Groupe du musée de l'Homme, the very first resistance network. He just had time to produce the last issue of the newsletter Résistance before narrowly escaping its dismantlement.   By then assuming a pivotal role in the ZO (Zone Occupée) Resistance, Brossolette coordinated contacts between groups such as Libération-Nord from Christian Pineau, the Organisation Civile et Militaire (OCM) and Comité d'Action Socialiste (CAS). He finally obtained a liaison with London and General Charles de Gaulle when he was hired by conservative Gilbert Renault also known as Colonel Rémy as press and propaganda manager of Confrérie Notre-Dame (CND), by then the most important network in Northern France. In April 1942, Brossolette met De Gaulle in London as representative of the ZO Resistance and was hired to work on bringing political credibility to De Gaulle to back his recognition as the only Free French Forces leader by the Allies in his feud against Henri Giraud in Algiers. At the same time, he was promoted to major (commandant) and awarded Compagnon de la Libération. Brossolette created the civilian arm of the BCRAM intelligence service, which became the Bureau Central de Renseignements et d'Action (BCRA), in liaison with the RF section of the British side, Special Operations Executive (SOE). Strong ties of camaraderie were forged between Brossolette (codenamed Brumaire, also known as Commandant Bourgat), BCRA's chief André Dewavrin (codenamed Arquebuse, also known as Colonel Passy) and SOE's Forest Frederick Edward Yeo-Thomas (codenamed Shelley, also known as The White Rabbit). De Gaulle set up his Free French intelligence system to combine both military and political roles, including covert operations. The policy was reversed in 1943 by Emmanuel d'Astier de La Vigerie (1900–1969), the Interior Minister, who insisted on civilian control of political intelligence.[1]  The three friends were sent on a mission to France and united, under the CCZN (Comité de Coordination de Zone Nord), the various ZO Resistance groups which had been thoroughly divided by political views, including the communist-led Front National (mission Arquebuse-Brumaire); they were thus instrumental in the merging with the ZL (Zone Libre) Resistance similarly united by Jean Moulin under the MUR. This led to the creation of the Conseil National de la Résistance (CNR) by Moulin through the addition of the political parties and unions and ultimately to De Gaulle's unequivocal recognition as Free France's political representative to the Allies. During this time, Pierre Brossolette resumed his radio chronicles on BBC with high-profile speeches to the "army of shadows", replacing Maurice Schumann as anchor (38 times). In a speech at the Albert Hall on 18 June 1943, he famously praised the soutiers de la gloire (or "stokers of glory") in a reference to the fallen anonymous soldiers and resistants. Brossolette also resumed his newspaper work through a series of articles on France's situation, including one in La Marseillaise considered by many to be the doctrinal founding of the Gaullisme de guerre movement. PoliticsIn addition to journalism, Pierre Brossolette was also a politician. He was a protégé of Léon Blum and was considered an up-and-coming star of the SFIO party, running elections on his Troyes (Champagne) base. He assumed cabinet functions during the Popular Front government and as a political pundit on official Radio PTT he was considered the de facto foreign policy spokesman of the socialist government. Already calling for deep rejuvenation of the political class before the war, he attributed French defeat in 1940 to the corrupt political system of the Third Republic. As he politically structured the Parisian resistance, Brossolette succeeded in convincing the network leaders to create a temporary Resistance Party under De Gaulle's leadership after the war, focused on promoting ambitious social transformations while avoiding the predictable enmity and chaos of post-Liberation times. This political and social plan, including nationalisations and price controls, inspired the March 1944 Conseil national de la Résistance programme and was implemented after war. Brossolette's criticism of the old parliamentarian system, together with the role of communist networks inside the CNR, became the main point of disagreement with his southern counterpart Jean Moulin. His desire to disband all the old parties through a complete reshuffle of ideological lines logically brought him into conflict with the party leaders. As a result, he was excluded from the newly reconstituted SFIO party by Daniel Mayer and Gaston Defferre a few days before being arrested,[2] although the decision to remove him from the party was never enforced and was actually forgotten. Despite this, most of his ideas were implemented in 1958 when De Gaulle established the Fifth Republic and established a presidentialist system based around his Rally of the French People (RPF) party. However, De Gaulle was pushed in the short term to decide in favour of Jean Moulin's proposal as he still struggled to show the Allies (Americans in particular) that he was not a dictator. Brossolette's ideas of a Resistance party raised many opponents' fears of a "bonapartian" drift, especially among fellow socialists in London including Pierre Cot and Raymond Aron. This seemed to be confirmed to his detractors' eyes when Brossolette succeeded a bold blow against the Vichy regime by exfiltrating from France Charles Vallin, deputy leader of conservative French Social Party (PSF) that had surged as the main French party with over 30% at pre-war elections, but deemed proto-fascist by the left. Hence the French Fourth Republic eventually reverted to the Third Republic's pre-war parliamentarist system. During his last missions, Brossolette worked on creating a new party that could be the major force of the left. He was inspired by the British Labour Party, using a non-Marxist or, at least, reformist approach (thus effectively challenging the French Socialist Party). For that, he spent his last days writing an ambitious critique of Marx's political philosophy as a by-product of 18th-century rationalism that would provide the theoretical framework for this party. Unfortunately, at the time of his arrest the manuscripts were thrown overboard at sea over Brittany shores.[3] ArrestBrossolette returned to Paris for a third mission to reorganise the Parisian resistance which was in disarray after successive Gestapo raids, especially by CND's dismantling. By then, his role and importance was already well known to the SS Intelligence Services after Moulin's death and despite De Gaulle's clear reluctance to appoint him as substitute CNR chief. He escaped arrest many times and was summoned to return to Britain by late 1943 to introduce the newly appointed CNR chief, Émile Bollaert, to De Gaulle. The bad winter weather cancelled many Lysander exfiltration attempts (conducted only under moonlight) or Lysanders would be shot down as in a December attempt near Laon, so in February 1944, they decided to return by boat from Brittany. However, the vessel, hit by a storm, shipwrecked at Pointe du Raz. They managed to reach the coast and to be hidden by local Resistance, but were betrayed by a local woman at a checkpoint. Bollaert and Brossolette were not identified and were kept imprisoned in Rennes for weeks. F. F. E. Yeo-Thomas, when informed of Brossolette's capture, decided to be immediately parachuted onto the continent and organise his escape. Nevertheless, they were recognised before the planned action and taken to the Intelligence Services (Sicherheitsdienst) headquarters on Avenue Foch by senior SD officer Ernst Misselwitz in person on 19 March. It was recently confirmed that he was identified by a semi-coded report to London from CNR's Claude Bouchinet-Serreules and Jacques Bingen written by the services of Daniel Cordier intercepted at the Pyrenees, tragically self-fulfilling the severe criticism of Brossolette and Yeo-Thomas about the lack of prudence inside the Parisian Délégation générale. Yeo-Thomas himself would be captured as he prepared a bold escape from Rennes Prison wearing German uniforms with the help of Brigitte Friang. Both Yeo-Thomas and Friang were captured before planned action as many Parisian networks were dismantled following the so-called "Rue de la Pompe affair" (after the location of the Delegation générale) and Pierre Manuel's avows.[4] Torture and death Brossolette was tortured at 84 Avenue Foch in Paris, enduring severe beatings and waterboardings over a two-and-a-half-day period. On 22 March, while he was left alone and recovered some consciousness, he threw himself through the window of the garret room of the building's sixth floor.[5] Since he had not swallowed his cyanide capsule when captured in Rennes, he was afraid of implicating others and probably chose to silence himself. There was a widespread belief among resistants that it was difficult, if not impossible, not to speak under torture. He died later in the evening at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital. On 24 March, he was cremated at Père Lachaise Cemetery. His ashes were kept at Père Lachaise Cemetery's columbarium, urn 3913 according to official cemetery records.[5] Brossolette's reportedly last words were enigmatic: "all will be fine Tuesday". Posterity From after the war until the late 1950s, Brossolette was considered the main leader of the French Resistance, though many were claimed heroes by their political family (such as Honoré d'Estienne d'Orves by royalists and Gabriel Péri by communists). Brossolette's fame was helped by his media notoriety before the war on Radio-PTT and on wartime BBC emissions, his networking role that made his name or codename known and remembered over almost every Resistance member in northern France and by flattering early accounts of BCRA's chief Passy in his memoirs although he had also created, through his independent position and sarcastic wit, many enemies among party leaders, Gaullists, communists and even socialists that survived him.[6][4] De Gaulle himself thought otherwise and as he started writing his memoirs in 1954 and later assumed power, he attributed the main leading role to his by-then relatively unknown representative Jean Moulin rather than field leaders as De Gaulle emphasized the top-down unification that objectively allowed him to be recognized by the Allies. This was formalized in 1964 by the transfer of Moulin's ashes to the Panthéon, and backed by an emotional speech by André Malraux.[7] With time, Brossolette was relegated to a second place and became the hero of his party SFIO while Moulin came to symbolize the myth of the French Resistance unity while the country struggled with the Algerian war and as De Gaulle tried to avoid civil war calling for union while noticing the growing popular clout of the Resistance legend on the postwar imagination.[8] Later, Brossolette's memory suffered another blow when the 1981-elected socialist president François Mitterrand chose to honour Moulin at a Panthéon investiture ceremony instead of rehabilitating Brossolette's role. This further enhanced his relegation – even inside the socialist political family, as evidenced by the modest celebrations of his birth centenary in 2003 and the SFIO/PS centenary.[9] At the time, a senior party official Harlem Désir (currently secretary-general of the PS) anecdotally told that the most important figure of the party's century was Jean Moulin – who actually never was a party member and deemed instead close to the Radical Party. Since then, he has been fairly better remembered than heroes such as Bingen, Jean Cavaillès or Berty Albrecht[10] or important leaders such as Henri Frenay, but overall eclipsed by Moulin's popularity. More recently in 2013, a support committee presided by historian Mona Ozouf was set up to bid for the transfer of Pierre Brossolette's ashes to the Panthéon, backed by an internet petition at the committee's site. On 21 February 2014, France's President François Hollande announced the transfer of Pierre Brossolette's ashes to the Panthéon with 3 other resistants Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz and Germaine Tillion, as well as a former pre-war Minister Jean Zay. Brossolette's ashes were kept at the columbarium of Père Lachaise Cemetery (urns 3902 or 3913) until his entrance to the Panthéon, which was celebrated on 27 May 2015. HomagesIn France today, Brossolette's name is better known than the man himself or his life achievements, thanks to the great number of streets – nearly 500 out of which 127 in Greater Paris, schools and public facilities bearing it (see below). His widow Gilberte was prominent in relaying his political ideas. In the 1950s, she was the first woman to enter – and, as vice-president, occasionally preside over – the French Senate. In Paris, a small street in the Quartier Latin between Rue Érasme and Rue Calvin, near École Normale Supérieure, was christened Rue Pierre-Brossolette in 1944 as among the very few celebrating a 20th-century person, together with Pierre and Marie Curie.[11] A notable exception is Lyon, probably illustrating the rivalries between the two Zones as conversely no street in Paris had been christened after Jean Moulin until 1965. Buildings in Paris such as the former bookstore and nearby Lycée Janson de Sailly's court at Rue de la Pompe, the residence at Rue de Grenelle, his birthplace at rue Michel-Ange, the Maison de Radio France and the Ministry of the Interior's court at Rue des Saussaies all feature commemorative plaques and his name is mentioned on a floor plaque at the Panthéon. In Narbonne plage, a unique aeolian memorial attests to his popularity in the early postwar years and marks the place of his exfiltration by felucca Seadog.[12] In Saint-Saëns, a stele commemorates the first Lysander exfiltration to London[13] and nearby Plogoff another marks the failed Brittany exfiltration attempt. Brossolette was also featured in the first series of Heroes of the Resistance by French PTT in 1957. The Saint-Cyr Military Academy ROTC Class of 2004 was christened after Brossolette, and a class song was created for the occasion.[14] The masonic Grande Loge de France named its cultural circle after Condorcet-Brossolette. Military honours

Operations and missions

See alsoNotesReferences

Sources

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||