|

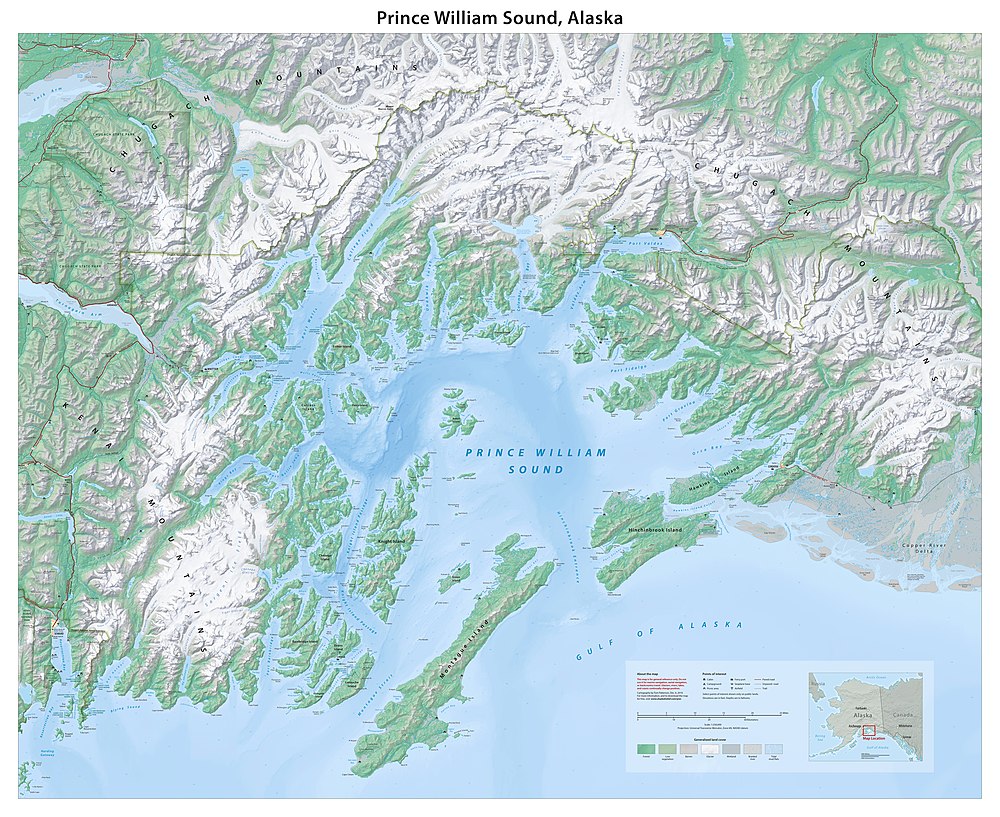

Prince William Sound Prince William Sound (Sugpiaq: Suungaaciq) is a sound off the Gulf of Alaska on the south coast of the U.S. state of Alaska. It is located on the east side of the Kenai Peninsula. Its largest port is Valdez, at the southern terminus of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System. Other settlements on the sound, which contains numerous small islands, include Cordova and Whittier plus the Alaska native villages of Chenega and Tatitlek. HistoryJames Cook entered Prince William Sound in 1778 and initially named it Sandwich Sound, after his patron the Earl of Sandwich. Later that year, the Sound was named to honour George III's third son Prince William Henry, then aged 13 and serving as a midshipman in the Royal Navy. In 1790, the Spanish explorer Salvador Fidalgo entered the sound, naming many of its features. Some places in the sound still bear the names given by Fidalgo, as Port Valdez, Port Gravina or Cordova. The explorer landed on the actual site of Cordova and took possession of the land in the name of the king of Spain. In 1793, Alexander Andreyevich Baranov founded port Voskresenskii, modern-day Seward, on the south edge of the Sound, which he called Chugach Bay.[1] The three-masted ship, Phoenix, was built there, the first ship built by the Russians in America.  Annie Montague Alexander led an expedition through the Sound in 1908.[2] A tsunami on March 27, 1964, a result of the Good Friday earthquake, killed a number of Chugach villagers in the coastal village of Chenega and destroyed the town of Valdez. Lasting four minutes and thirty-eight seconds, the magnitude 9.2 megathrust earthquake remains the most powerful earthquake recorded in North American history, and the third most powerful earthquake recorded in world history. In Prince William Sound, Port Valdez suffered a massive underwater landslide, resulting in the deaths of 32 people between the collapse of the Valdez city harbor and docks, and inside the ship that was docked there at the time. Nearby, a 27-foot (8.2 m) tsunami destroyed the village of Chenega, killing 23 of the 68 people who lived there; survivors out-ran the wave, climbing to high ground. Post-quake tsunamis severely affected Whittier, Seward, Kodiak, and other Alaskan communities, as well as people and property in British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California. Two types of tsunamis were produced by this subduction zone earthquake. There was a tectonic tsunami produced in addition to about 20 smaller and local tsunamis. These smaller tsunamis were produced by submarine and subaerial landslides and were responsible for the majority of the tsunami damage. Tsunami waves were noted in over 20 countries, including Peru, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Japan, Mexico, and Antarctica. The largest tsunami wave was recorded in Shoup Bay, Alaska, with a height of about 220 ft (67 m). On March 24, 1989, the oil tanker Exxon Valdez ran aground on Bligh Reef after leaving Valdez, causing a large oil spill, which resulted in massive damage to the environment, including the killing of around 250,000 seabirds, nearly 3,000 sea otters, 300 harbour seals, 250 bald eagles and up to 22 killer whales. It is considered to be one of the worst human-caused environmental disasters. The Valdez spill is the second largest in US waters, after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, in terms of volume released. The oil, originally extracted at the Prudhoe Bay Oil Field, eventually impacted 1,300 miles (2,100 km) of coastline, of which 200 miles (320 km) were heavily or moderately oiled with an obvious impact. Chemical dispersant, a surfactant and solvent mixture, was applied to the slick by a private company on March 24 with a helicopter. But the helicopter missed the target area. Scientific data on its toxicity were either thin or incomplete. In addition, public acceptance of a new, widespread chemical treatment was lacking. Landowners, fishing groups, and conservation organizations questioned the use of chemicals on hundreds of miles of shoreline when other alternatives may have been available. Because Prince William Sound contained many rocky coves where the oil collected, the decision was made to displace it with high-pressure hot water. However, this also displaced and destroyed the microbial populations on the shoreline; many of these organisms (e.g. plankton) are the basis of the coastal marine food chain, and others (e.g. certain bacteria and fungi) are capable of facilitating the biodegradation of oil. At the time, both scientific advice and public pressure was to clean everything, but since then, a much greater understanding of natural and facilitated remediation processes has developed, due somewhat in part to the opportunity presented for study by the Exxon Valdez spill. Despite the extensive cleanup attempts, less than ten percent of the oil was recovered. In May 2020, a team of researchers announced that a certain mile-long slope on the Barry Arm fjord in Prince William Sound would likely trigger a catastrophic tsunami within the next two decades, or possibly even within the next twelve months. The researchers cautioned their analysis had not yet been peer-reviewed. The Alaska Department of Natural Resources subsequently issued a warning that "an increasingly likely landslide could generate a wave with devastating effects on fishermen and recreationalists".[3] GeographyMost of the land surrounding Prince William Sound is part of the Chugach National Forest, the second largest national forest in the U.S. Prince William Sound is ringed by the steep and glaciated Chugach Mountains. The coastline is convoluted, with many islands and fjords, several of which contain tidewater glaciers. The principal barrier islands forming the sound are Montague Island, Hinchinbrook Island, and Hawkins Island. References

External links

|