|

Rashomon

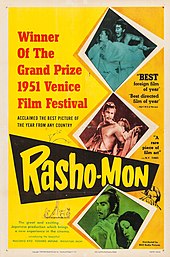

Rashomon (Japanese: 羅生門, Hepburn: Rashōmon)[a] is a 1950 Japanese jidaigeki film directed by Akira Kurosawa from a screenplay he co-wrote with Shinobu Hashimoto. Starring Toshiro Mifune, Machiko Kyō, Masayuki Mori, and Takashi Shimura, it follows various people who describe how a samurai was murdered in a forest. The plot and characters are based upon Ryūnosuke Akutagawa's short story "In a Grove", with the title and framing story taken from Akutagawa's "Rashōmon". Every element is largely identical, from the murdered samurai speaking through a Shinto psychic to the bandit in the forest, the monk, the assault of the wife, and the dishonest retelling of the events in which everyone shows their ideal self by lying. Production began in 1948 at Kurosawa's regular production firm Toho but was canceled as it was viewed as a financial risk. Two years later, Sōjirō Motoki pitched Rashomon to Daiei Film upon the completion of Kurosawa's Scandal. Daiei initially turned it down but eventually agreed to produce and distribute the film. Principal photography lasted from July 7 to August 17, 1950, taking place primarily in Kyoto on an estimated ¥15–20 million budget. When creating the film's visual style, Kurosawa and cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa experimented with various methods such as pointing the camera at the sun, which was considered taboo. Post-production took only one week and was decelerated by two fires. Rashomon premiered at the Imperial Theatre on August 25, 1950, and was distributed throughout Japan the following day, to moderate commercial success, becoming Daiei's fourth highest-grossing film of 1950. Japanese critics praised the experimental direction and cinematography but criticized its adapting of Akutagawa's story and complexity. Upon winning the Golden Lion at the 12th Venice International Film Festival, Rashomon became the first Japanese film to attain significant international reception, garnering critical acclaim and earning roughly $800,000 abroad. It later won Best Foreign Language Film at the 24th Academy Awards,[b] and was nominated for Best Film at the 6th British Academy Film Awards. Rashomon is now considered one of the greatest films ever made and among the most influential movies from the 20th century. It pioneered the Rashomon effect, a plot device that involves various characters providing subjective, alternative, and contradictory versions of the same incident. In 1999, critic Andrew Johnston asserted that "the film's title has become synonymous with its chief narrative conceit". PlotIn Heian-era Kyoto, a woodcutter and a priest, taking shelter from a downpour under the Rashōmon city gate, recount a story of a recent assault and murder. Baffled at conflicting accounts of the same event, the woodcutter and the priest are joined by a commoner. The woodcutter claims he had found the body of a murdered samurai three days earlier, alongside the samurai's cap, his wife's hat, cut pieces of rope, and an amulet. The priest claims he had seen the samurai travel with his wife on the day of the murder. Both testify in court before a policeman presents the main suspect, a captured bandit named Tajōmaru. In Tajōmaru's version of events, he follows the couple after spotting them traveling in the woods. He tricks the samurai into leaving the trail by lying about finding a burial pit filled with ancient artifacts. He subdues the samurai and attempts to rape his wife, who tries to defend herself with a dagger. Tajōmaru then seduces the wife, who, ashamed of the dishonor of having been with two men, asks Tajōmaru to duel her husband so she may go with the man who wins. Tajōmaru agrees; the duel ends with Tajōmaru killing the samurai. He then finds the wife has fled. The wife, having been found by the police, delivers a different testimony; in her version of events, Tajōmaru leaves immediately after assaulting her. She frees her husband from his bonds, but he stares at her with contempt and loathing. The wife tries to threaten him with her dagger but then faints from panic. She awakens to find her husband dead, with the dagger in his chest. In shock, she wanders through the forest until coming upon a pond and attempts to drown herself but fails. The samurai's testimony is heard through a medium. In his version of events, Tajōmaru asks the wife to marry him after the assault. To the samurai's shame, she accepts, asking Tajōmaru to kill the samurai first. This disgusts Tajōmaru, who gives the samurai the choice to let her go or have her killed. The wife then breaks free and flees. Tajōmaru unsuccessfully gives chase. After being set free by an apologetic Tajōmaru, the samurai kills himself with the dagger. Later, he feels someone remove the dagger from his chest, but cannot tell who. The woodcutter proclaims that all three stories are falsehoods and admits that he saw the samurai killed by a sword instead of a dagger. The commoner pressures the woodcutter to admit that he had seen the murder but lied to avoid getting in trouble. In the woodcutter's version of events, Tajōmaru begs the wife to marry him. She instead frees her husband, expecting him to kill Tajōmaru. The samurai refuses to fight, unwilling to risk his life for a ruined woman. Tajōmaru rescinds his promise to marry the wife; the wife rebukes them both for failing to keep their promises. The two men unwillingly enter into a duel; the samurai is disarmed and begs for his life, and Tajōmaru kills him. The wife flees, and Tajōmaru steals the samurai's sword and limps away. The woodcutter, the priest, and the commoner are interrupted by the sound of a crying baby. They find a child abandoned in a basket along with a kimono and an amulet; the commoner steals the items, for which the woodcutter rebukes him. The commoner deduces that the woodcutter had lied not because he feared getting in trouble, but because he had stolen the wife's dagger to sell for food. Meanwhile, the priest attempts to soothe the baby. The woodcutter attempts to take the child after the commoner's departure; the priest, having lost his faith in humanity after the events of the trial and the commoner's actions, recoils. The woodcutter explains that he intends to raise the child. Having seen the woodcutter's well-meaning intentions, the priest announces that his faith in men has been restored. As the woodcutter prepares to leave, the rain stops and the clouds part, revealing the sun. Cast

Production

DevelopmentAccording to Donald Richie, Akira Kurosawa began developing the film circa 1948, and both Kurosawa's regular production studio Toho and its financing company, Toyoko Company, refused to produce the film, with the latter fearing it would be a precarious production. Following the completion of Scandal, Sōjirō Motoki offered the script to Daiei who also initially rejected it.[4][5][6] Regarding Rashomon, Kurosawa said:

As with most films produced in post-war Japan, reports on the budget of Rashomon are scarce and differ.[7] In 1952, Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha said that the film's production cost was ¥20 million, and suggested that advertising and other expenses brought the overall budget to ¥35 million.[8] The following year, the National Board of Review reported that the $85,000 spent on Kurosawa's Ikiru (1952) was over twice the budget of Rashomon.[9] According to the UNESCO in 1971, Rashomon had a budget of ¥15 million or $42,000.[10] Reports on the budget in Western currency vary: The Guinness Book of Movie Facts and Feats cited it as $40,000,[11] The New York Times and Stuart Galbraith IV noted a reputed $140,000 figure,[12][13] and a handful of other sources have claimed that it cost as high as $250,000. Jasper Sharp disputed the latter number in an article for the BBC, since it would have been equal to ¥90 million at the time of the film's production. He added that it "seems highly unlikely given that the 125 million yen, approximately $350,000, that Kurosawa subsequently spent on Seven Samurai four years later made this film by far the most expensive domestic production up to this point".[7] WritingKurosawa wrote the screenplay while staying at a ryokan in Atami with his friend Ishirō Honda, who was scripting The Blue Pearl (1951). The pair regularly commenced writing their respective films at 9:00 a.m. and would give feedback on each other's work after each completed roughly twenty pages. According to Honda, Kurosawa soon refused to read The Blue Pearl after a couple of days but "of course, he still made me read his".[6] CastingKurosawa had initially wanted the cast of eight to consist entirely of previous collaborators, specifically counseling Toshiro Mifune and Takashi Shimura. He also suggested that Setsuko Hara—who had played the lead in No Regrets for Our Youth (1946)—portray the wife, but she was not cast since her brother-in-law, filmmaker Hisatora Kumagai, was against it; Hara would subsequently appear in Kurosawa's next film, The Idiot (1951).[14] Daiei executives then recommended Machiko Kyō, believing she would make the film easier to market. Kurosawa agreed to cast her upon seeing her show enthusiasm for the project by shaving her eyebrows before going for a make-up test. When Kurosawa shot Rashomon, the actors and the staff lived together, a system Kurosawa found beneficial. He recalls:

FilmingDue to its small budget the film had only three sets: the gate; the forest scene; and the police courtyard. Filming began on 7 July 1950 and ended on 17 August. After a week's work on post-production, it was released in Tokyo on 25 August.[16] The cinematographer, Kazuo Miyagawa, contributed numerous ideas, technical skill and expertise in support for what would be an experimental and influential approach to cinematography. For example, in one sequence, there is a series of single close-ups of the bandit, then the wife and then the husband, which then repeats to emphasize the triangular relationship between them.[17] The use of contrasting shots is another example of the film techniques used in Rashomon. According to Donald Richie, the length of time of the shots of the wife and of the bandit is the same when the bandit is acting barbarically and the wife is hysterically crazy.[18] Rashomon had camera shots that were directly into the sun. Kurosawa wanted to use natural light, but it was too weak; they solved the problem by using a mirror to reflect the natural light. The result makes the strong sunlight look as though it has traveled through the branches, hitting the actors. The rain in the scenes at the gate had to be tinted with black ink because camera lenses could not capture the water pumped through the hoses.[19] Lighting Robert Altman compliments Kurosawa's use of "dappled" light throughout the film, which gives the characters and settings further ambiguity.[20] In his essay "Rashomon", Tadao Sato suggests that the film (unusually) uses sunlight to symbolize evil and sin in the film, arguing that the wife gives in to the bandit's desires when she sees the sun.[citation needed] Professor Keiko I. McDonald opposes Sato's idea in her essay "The Dialectic of Light and Darkness in Kurosawa's Rashomon." McDonald says the film conventionally uses light to symbolize "good" or "reason" and darkness to symbolize "bad" or "impulse". She interprets the scene mentioned by Sato differently, pointing out that the wife gives herself to the bandit when the sun slowly fades out. McDonald also reveals that Kurosawa was waiting for a big cloud to appear over Rashomon gate to shoot the final scene in which the woodcutter takes the abandoned baby home; Kurosawa wanted to show that there might be another dark rain any time soon, even though the sky is clear at this moment. McDonald regards it as unfortunate that the final scene appears optimistic because it was too sunny and clear to produce the effects of an overcast sky. Post-productionStanley Kauffmann writes in The Impact of Rashomon that Kurosawa often shot a scene with several cameras at the same time, so that he could "cut the film freely and splice together the pieces which have caught the action forcefully as if flying from one piece to another." Despite this, he also used short shots edited together that trick the audience into seeing one shot; Donald Richie says in his essay that "there are 407 separate shots in the body of the film ... This is more than twice the number in the usual film, and yet these shots never call attention to themselves."[citation needed] Due to setbacks and some lost audio, Mifune returned to the studio after filming to record another line. Recording engineer Iwao Ōtani added it to the film along with the music, using a different microphone.[21] The film was scored by Fumio Hayasaka, who is among the most respected of Japanese composers.[22] At the director's request, he scored a bolero for the woman's story.[23] Allegorical and symbolic contentThe film depicts the rape of a woman and the murder of her samurai husband through the widely differing accounts of four witnesses, including the bandit-rapist, the wife, the dead man (speaking through a medium), and lastly the woodcutter, the one witness who seems the most objective and least biased. The stories are mutually contradictory and even the final version may be seen as motivated by factors of ego and saving face. The actors kept approaching Kurosawa wanting to know the truth, and he claimed the point of the film was to be an exploration of multiple realities rather than an exposition of a particular truth. Later film and television use of the "Rashomon effect" focuses on revealing "the truth" in a now conventional technique that presents the final version of a story as the truth, an approach that only matches Kurosawa's film on the surface. Due to its emphasis on the subjectivity of truth and the uncertainty of factual accuracy, Rashomon has been read by some as an allegory of the defeat of Japan at the end of World War II. James F. Davidson's article, "Memory of Defeat in Japan: A Reappraisal of Rashomon" in the December 1954 issue of the Antioch Review, is an early analysis of the World War II defeat elements.[24] Another allegorical interpretation of the film is mentioned briefly in a 1995 article, "Japan: An Ambivalent Nation, an Ambivalent Cinema" by David M. Desser.[25] Here, the film is seen as an allegory of the atomic bomb and Japanese defeat. It also briefly mentions James Goodwin's view on the influence of post-war events on the film. However, the film's source material, "In a Grove", was published in 1922, so any postwar allegory would have resulted from Kurosawa's additions rather than the story about the conflicting accounts. Historian and critic David Conrad has noted that the use of rape as a plot point came at a time when American occupation authorities had recently stopped censoring Japanese media and belated accounts of rapes by occupation troops began to appear in Japanese newspapers. Moreover, Kurosawa and other filmmakers were not allowed to make jidaigeki during the early part of the occupation, so setting a film in the distant past was a way to reassert domestic control over cinema.[26] ReleaseBox office The premiere of Rashomon took place at the Imperial Theatre on August 25, 1950, in Tokyo, and was distributed nationwide by Daiei the next day. It was an instant box office success, leading several theaters to continue to play it for two or three weeks rather than a Japanese film's regular one-week theatrical run. Jiji Press reported that the film was Daiei's third highest-grossing film released between September 1949 and August 1950, having earned over ¥10 million.[27] In general, the film was Daiei's fourth-highest-grossing film of 1950. Donald Richie claimed that it was also one of the top ten highest-earning films in Japan that year.[28] The film later became Kurosawa's first major international hit.[29] It was released theatrically in the United States by RKO Radio Pictures on December 26, 1951, in both subtitled and dubbed versions.[30] In Europe, the film sold 365,293 tickets in France and Spain,[31] and 8,292 tickets in other European countries between 1996 and 2020,[32] for a combined total of at least 373,585 tickets sold in Europe. By June 1952, the film had grossed $700,000 overseas.[33] Later that same year, Scene reported that the film had earned $800,000 (¥300 million) overseas, which was $200,000 more than what all of the previous Japanese movies released overseas had collectively grossed outside of Japan within the past four years.[34] In 1954, Kinema Junpo stated that it grossed $500,000 in 1951, and reached roughly $800,000 shortly thereafter.[35] According to the National Board of Review, Rashomon exceeded $300,000 in the United States alone.[36] In 2002, the film grossed $46,808 in the US,[37] with an additional earned $96,568 during 2009 to 2010,[38] for a combined $143,376 in the United States between 2002 and 2010. Venice Film Festival screeningJapanese film companies had no interest in international festivals and were reluctant to submit the movie because paying for printing and creating subtitles was considered a waste of money. The film was subsequently screened at the 1951 Venice Film Festival at the behest of Italifilm president Giuliana Stramigioli, who had recommended it to the Italian film promotion agency Unitalia Film seeking a Japanese film to screen at the festival. In 1953, Stramigioli explained her reasoning behind submitting the film:

However, Daiei and other Japanese corporations disagreed with the choice of Kurosawa's work because it was "not [representative enough] of the Japanese movie industry" and felt that a work of Yasujirō Ozu would have been more illustrative of excellence in Japanese cinema. Despite these reservations, the film was screened at the festival. Before it was screened at the Venice festival, the film initially drew little attention and had low expectations at the festival, as Japanese cinema was not yet taken seriously in the West at the time. But once it had been screened, Rashomon drew an overwhelmingly positive response from festival audiences, praising its originality and techniques while making many question the nature of truth.[40] The film won both the Italian Critics Award and the Golden Lion award—introducing Western audiences, including Western directors, more noticeably to both Kurosawa's films and techniques, such as shooting directly into the sun and using mirrors to reflect sunlight onto the actor's faces. Home mediaKadokawa released Rashomon on DVD in May 2008 and Blu-ray in February 2009.[41] The Criterion Collection later issued a Blu-ray and DVD edition of the film based on the 2008 restoration, accompanied by a number of additional features.[42] ReceptionCritical responseJapanese reviewsRashomon was met with mixed reviews from Japanese critics upon its release.[13][43] When it received positive responses in the West, Japanese critics were baffled: some decided that it was only admired there because it was "exotic"; others thought that it succeeded because it was more "Western" than most Japanese films.[44] Tadashi Iijima criticized "its insufficient plan for visualizing the style of the original stories". Tatsuhiko Shigeno of Kinema Junpo opposed Mifune's extensive dialogue as unfitting for the role of a bandit. Akira Iwasaki later cited how he and his contemporaries were "impressed by the boldness and excellence of director Akira Kurosawa's experimental approach within this movie, but couldn't help but notice that there was some confusion in its expression" adding that "I found it difficult to resonate with the agnostic philosophy that the film contains wholeheartedly".[45] In a collection of interpretations of Rashomon, Donald Richie writes that "the confines of 'Japanese' thought could not contain the director, who thereby joined the world at large".[46] Regarding the film's Japanese reception, Kurosawa remarked:

International reviewsRashomon received mostly acclaim from Western critics.[48][49] Ed Sullivan gave the film a positive review in Hollywood Citizen-News, calling it "an exciting evening, because the direction, the photography and the performances will jar open your eyes." He praised Akutagawa's original plot, Kurosawa's impactful direction and screenplay, Mifune's "magnificent" villainous performance, and Miyagawa's "spellbinding" cinematography that achieves "visual dimensions that I've never seen in Hollywood photography" such as being "shot through a relentless rainstorm that heightens the mood of the somber drama."[50] Meanwhile, Time was critical of the film, finding it "draggy" and noted that its score "borrows freely" from Maurice Ravel's Boléro.[3] Boléro controversyThe usage of a musical composition similar to Ravel's Boléro provoked wide controversy, especially in Western countries.[51] Some accused Hayasaka of music plagiarism,[52] including Boléro's publisher, who sent him a letter of protest after the film's French release.[51] In late 1950, the film was vetoed from Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan's selection list for the 4th Cannes Film Festival over concerns about facing copyright issues for the composition. Masaichi Nagata's responseDaiei's president, Masaichi Nagata, was initially critical of the film.[4][53][54] Assistant director Tokuzō Tanaka said that Nagata broke the abrupt few minutes of silence following its preview screening at the company's headquarters in Kyōbashi by saying "I don't really get it, but it's a noble photograph".[55] According to Kurosawa, Nagata had called Rashomon "incomprehensible" and loathed it so much that he ended up demoting its producer.[54] Nagata later embraced Rashomon upon it receiving numerous awards and international success.[4] He kept the original Golden Lion that the film received in his office, and had replicas handed to Kurosawa and others who worked on the film. His constant reference to its accomplishments as if he was responsible for the film himself was stated by many.[53][54] In 1992, Kurosawa remarked that Nagata had cited Rashomon's cinematographic feats in an interview included for the film's first television broadcast without mentioning the names of its director or cinematographer. He reflected being disgusted by the company's president taking credit for the film's achievements: "Watching that television interview, I had the feeling that I was back in the world of Rashomon all over again. It was as if the pathetic self-delusions of the ego, those failings I had attempted to portray in the film, were being exhibited in real life. People do indeed have immense difficulty talking about themselves as they really are. I was reminded once again that the human animal suffers from the trait of instinctive self-aggrandizement."[54] Some modern sources have erroneously credited Nagata as the film's producer. AccoladesLegacy

Associated filmsThe international success of Rashomon led Daiei to produce several subsequent jidaigeki films featuring Kyō as the lead.[47] Among these were Kōzaburō Yoshimura's The Tale of Genji (1951), Teinosuke Kinugasa's Dedication of the Great Buddha (1952) and Gate of Hell (1953), Kenji Mizoguchi's Ugetsu (1953), and Keigo Kimura's The Princess Sen (1954), all of which received screenings overseas.[61] In 1952, Daiei produced a Western-targeted epic, titled Beauty and the Thief,[62] with the intent of obtaining a second Golden Lion.[63][64][f] Based on another story by Akutagawa, composed by Hayasaka, and starring Kyō, Mori, Shimura, Katō, and Honma, the film has been described as an inferior imitator of Rashomon and has since faded into obscurity.[65][47] Mifune was also initially going to appear in Beauty and the Thief as suggested by a photograph of him taken by Werner Bischof during production in 1951 when the film was allegedly titled "Hokkaido".[66] Cultural impactRashomon has been cited as "one of the most influential films of the 20th century".[67] In the early 1960s, film historians credited Rashomon as the start of the international New Wave cinema movement, which gained popularity during the late 1950s to early 1960s.[40] It has since been cited as an inspiration for numerous films from around the world, including Andha Naal (1954),[68] Valerie (1957),[69] Last Year at Marienbad (1961),[70] Yavanika (1982),[71] Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs (1992)[72] and Pulp Fiction (1994),[7] The Usual Suspects (1995),[7] Courage Under Fire (1996),[73] Tape (2001),[7] Hero (2002),[7] and Fast X (2023).[74] The television shows All in the Family (1971–1979),[73] Frasier (1993–2004), and The Acolyte (2024)[75] made episodes inspired by the film. Some have compared Monster (2023) to the film;[73] however, director Hirokazu Kore-eda claimed its similarities are merely coincidental.[76] Ryan Reynolds' initial proposal for Deadpool & Wolverine (2024) was for it to have a plot similar to Rashomon.[73]

In a 1998 issue of Time Out New York, Andrew Johnston wrote:

Remakes and adaptationsIt spawned numerous remakes and adaptations across film, television and theatre.[78][79] Examples include:

Retrospective reassessmentIn the years following its release, several publications have named Rashomon one of the greatest films of all time, and it is also cited in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.[91] On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 98% of 63 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 9.2/10. The website's consensus reads: "One of legendary director Akira Kurosawa's most acclaimed films, Rashomon features an innovative narrative structure, brilliant acting, and a thoughtful exploration of reality versus perception."[92] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 98 out of 100, based on 18 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[93] Film critic Roger Ebert gave the film four stars out of four and included it in his Great Movies list.[94] Top listsThe film appeared on many critics' top lists of the best films.

PreservationIn 2008, the film was restored by the Academy Film Archive, the National Film Center of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, and Kadokawa Pictures, Inc., with funding provided by the Kadokawa Culture Promotion Foundation and The Film Foundation.[109] See alsoNotes

References

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Rashomon. Wikiquote has quotations related to Rashomon (film).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||