|

Robert Fraser (art dealer)

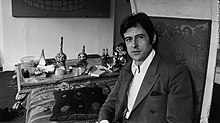

Robert Fraser (13 August 1937 – 27 January 1986), sometimes known as "Groovy Bob", was a London art dealer. He was a figure in the London cultural scene of the mid-to-late 1960s, and was close to members of the Beatles (particularly Paul McCartney) and the Rolling Stones. In February 2015, the exhibition A Strong Sweet Smell of Incense: A Portrait of Robert Fraser, curated by Brian Clarke, was presented by Pace Gallery at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Early life and educationRobert Fraser was born on 13 August 1937, the son of banker Sir Lionel Fraser, who had started as a newspaper delivery boy.[1] Lionel Fraser's father was butler to Harry Gordon Selfridge, the founder of the Selfridges department store chain.[2] Fraser was educated at Eton College, and spent several years in Africa in the 1950s as an officer in the King's African Rifles. CareerAfter a period spent working in galleries in the United States he returned to England, and with the help of his father (a wealthy financier who had also been a trustee of the Tate Gallery) established the Robert Fraser Gallery at 69 Duke Street (near Grosvenor Square), London, in 1962.[3] The gallery interior was designed by Cedric Price. The Robert Fraser Gallery became a focal point for modern art in Britain, and through his exhibitions he helped to launch and promote the work of many important new British and American artists including Peter Blake, Clive Barker, Bridget Riley, Jann Haworth, Richard Hamilton, Gilbert and George, Eduardo Paolozzi, Andy Warhol, Harold Cohen, Jim Dine and Ed Ruscha. Fraser also sold work by René Magritte, Jean Dubuffet, Balthus and Hans Bellmer. "Swinging Sixties"In 1966, the Robert Fraser Gallery was prosecuted for staging an exhibition of works by Jim Dine that was described as indecent (but not obscene). The works were removed from the gallery by the Metropolitan Police, and Fraser was charged under a 19th-century vagrancy law that applied to street beggars. He was fined 20 guineas and legal costs. Fraser became a trendsetter during the Sixties; Paul McCartney has described him as "one of the most influential people of the London Sixties scene". His London flat and his gallery were the foci of a "jet-set" salon of top pop stars, artists, writers and other celebrities, including members of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, photographer Michael Cooper, designer Christopher Gibbs, Marianne Faithfull, Dennis Hopper (who introduced Fraser to satirist Terry Southern), William Burroughs and Kenneth Anger. Because of this, he was given the nickname "Groovy Bob" by Terry Southern.[4] His flat at 23 Mount Street, on the third floor above Scott's restaurant, was described by Barry Miles as one of the "coolest sixties pads in London".[5] Fraser art-directed the cover for the Beatles' 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band – he dissuaded the group from using the original design, a psychedelic artwork created by the design collective The Fool, instead suggesting the pop artists Peter Blake and Jann Haworth, who created the famous collage cover design for which they each won a Grammy Award. It was through Fraser that Richard Hamilton was selected to design the poster for the White Album. His gallery also hosted You Are Here, Lennon's own foray into avant garde art during 1968. He was a close friend of the Rolling Stones and was present at the infamous 1967 party at Keith Richards' country house, Redlands, which was raided by police, leading to the subsequent arrests and trials of Mick Jagger, Richards, and Fraser on drug possession charges. The event is commemorated by the 1968 Richard Hamilton artwork Swingeing London 67,[6][7] a collage of contemporary press clippings about the case, and the portrait of Jagger and Fraser handcuffed together also entitled "Swingeing London".[8] Fraser always insisted that neither Jagger nor Richards actually had any drugs with them, and that everything found by the police actually belonged to him. During the raid he persuaded the officers that his 20 heroin pills were actually for an upset stomach and offered them only one for testing. Although Jagger and Richards were acquitted on appeal, Fraser pleaded guilty to charges of possession of heroin, and was sentenced to six months in prison.[9] After his release Fraser's interest in the gallery declined as his heroin addiction grew worse, and he closed the business in 1969.[citation needed] Fraser moved down the street to a large 8-room apartment on the 2nd floor of 120 Mount Street; the previous occupant was writer and theatre critic Kenneth Tynan. Keith Richards from the Rolling Stones was living with Fraser at the time, and it was here, sitting by the window in the lounge room, that Richards had the inspiration for the song Gimme Shelter

1970s and 1980s, and deathFraser left the UK and spent several years in India during the 1970s. He returned to London in the early 1980s and opened a second gallery in 1983, with a show of paintings by the stained glass and architectural artist Brian Clarke,[11] but by this time he was suffering from chronic drug and alcohol problems and the gallery never replicated the success of its predecessor, although Fraser was again influential in promoting the work of Clarke, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. It soon transpired that Fraser was also suffering from AIDS.[12] He was one of the first 'celebrity' victims of the disease in the UK.[13] In 1985, he sold his Cork Street gallery to Victoria Miro, who subsequently created the successful Victoria Miro Gallery. Fraser seemed disillusioned, and told her at the time "You'll never make a contemporary art gallery work in this country."[14] He was cared for by the Terence Higgins Trust during his final illness and died in January 1986. He died at his mother's flat in London.[15] Sources

Footnotes

|

||||||||||||