|

Rouen Cathedral

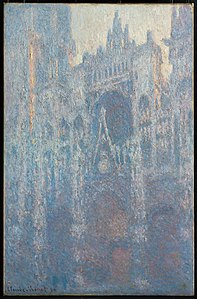

Rouen Cathedral (French: Cathédrale primatiale Notre-Dame de l'Assomption de Rouen) is a Catholic church in Rouen, Normandy, France. It is the see of the Archbishop of Rouen, Primate of Normandy.[4] It is famous for its three towers, each in a different style. The cathedral, built and rebuilt over a period of more than eight hundred years, has features from Early Gothic to late Flamboyant and Renaissance architecture.[5][4] It also has a place in art history as the subject of a series of impressionist paintings by Claude Monet, and in architecture history as from 1876 to 1880, it was the tallest building in the world.[6] HistoryFirst churchesChristianity was established in Rouen in about 260 by Saint Mellonius, who became the first bishop. The first church is believed to have been under or close to the present cathedral. In 395, a large basilica with three naves was built at the same site. In 755, the archbishop Rémy, the son of the Frankish statesman and military leader Charles Martel, established the first Chapter of the cathedral and constructed several courtyards and buildings around the church, including a palace for the archbishop.[7] The cathedral was enlarged by St. Ouen in 650, and visited by Charlemagne in 769. However, beginning in 841, a series of Viking raids seriously damaged the cathedral complex.[8][9] The Viking leader Rollo became first Duke of the Duchy of Normandy and was baptised in the Carolingian cathedral in 915 and buried there in 933. His grandson, Richard I of Normandy, further enlarged it in 950.[10] In the 1020s, the archbishop Robert began to rebuild the church in the Romanesque style, beginning with a new choir, crypt and ambulatory, and then a new transept. The Romanesque cathedral was consecrated by the archbishop Maurille on October 1, 1063, in the presence of William, Duke of Normandy, soon to become William the Conqueror after his conquest of England in 1066.[10] The Gothic cathedral The project for a cathedral in the new Gothic style was first launched by the Archbishop of Rouen, Hugues of Amiens, who had attended the consecration in 1144 of the Basilica of Saint-Denis, the first Gothic structure, with its emphasis upon filling the interior with light. In 1145, he began constructing a tower, now called the Tower Saint-Roman, in the new Gothic style.[10] A complete reconstruction of the cathedral was begun by his successor, Gautier the Magnificent. In 1185 he demolished the Romanesque nave and began building the western end of the sanctuary. He had completed the west front and first traverses when the work was interrupted by a major fire on Easter eve in 1200, which destroyed a large part of the town and seriously damaged the unfinished church and its furnishings. Gautier quickly repaired the damage and resumed the work, which was directed by his master mason, Jean d'Andeli. The nave was sufficiently complete by 1204 for King Philip II of France to be received there to celebrate the annexation of Normandy to the Kingdom of France. By 1207 the main altar was in place in the choir.[10] The first architectural addition to the new church was a series of small chapels between the buttresses on the north and south sides of the nave, requested by the city's prominent religious brotherhoods and corporations. In 1280 the surrounding spaces and buildings were modified to permit the construction of portals on the north and south transepts. The next addition was a response to the growing role of the Virgin Mary in church doctrine; the small axial chapel at the east end of the apse was replaced by a much larger chapel dedicated to her, begun in 1302. The west front was also given new decoration between 1370 and 1450.[11] Beginning in 1468 a highly ornamental new top, made of iron and covered with stone tiles, in the late Gothic Flamboyant style was added to the tower of Saint-Romaine.[11][12] 16th century – The Transition and the RenaissanceCardinal-Archbishop Georges d'Amboise (1494-1510) had a major influence on the church architecture. He incorporated into the Gothic design new Renaissance features, as he had done in his own residence, the Château de Gaillon, The first major project of the period was a new tower to match the old Saint-Romaine tower, built almost three centuries earlier. Work on the tower had begun in 1488, under master builder Guillaume Pontifs, but under Cardinal d'Amboise in 1496 the project was taken over 1496 by Jacques Le Roux, who had a more ambitious plan with Renaissance touches. The Pope authorised Cardinal d'Amboise to grant dispensations to consume milk and butter during Lent, in exchange for contributions to the tower. The new tower soon took on the nickname of the Butter Tower, though the money collected paid only a portion of the cost. [11][13]

As the new tower was being built, the west front of the Cathedral showed weaknesses and began to tilt. Cardinal d'Amboise ordered its complete reconstruction. This was carried out by master builder Rouilland Le Roux, nephew of Jacques Le Roux, in a lavishly ornate Flamboyant style. It was covered with layers of lacelike stone tracery, and hundreds of sculpted figures were added to the arch and niches of the portals. To stabilise the new facade, he added two massive buttresses, also richly decorated with sculpture. In addition to his changes to the Cathedral, the Cardinal and his architect reconstructed and decorated the Palace of the Archbishop close by, adding a new reception hall, galleries, gardens and fountains.[11] In 1514 the flèche, or spire of the cathedral, a lead-covered wooden spire over the lantern tower, fell. It was replaced within a few months in exactly the same form and with the same materials.[11] 17th–18th century

In the late 16th century the cathedral was badly damaged during the French Wars of Religion: in 1562 the Calvinists attacked the furniture, tombs, stained-glass windows and statuary. The cathedral was again struck by lightning in 1625 and 1642, then damaged by a hurricane in 1683.[14] In 1796, in the course of the French Revolution, the new revolutionary government nationalised the cathedral and transformed it for a time into a Temple of Reason. Some of the furniture and sculpture was sold, and the chapel railings were melted down to make cannon.[14] 19th century

In 1822 lightning started a fire that destroyed the wood and lead Renaissance spire of the central tower. The architect Jean-Antoine Alavoine proposed to replace it with a new spire made of cast iron. The idea of an iron spire was highly controversial; the novelist Gustave Flaubert denounced it as "the dream of a metal-worker in a delirium." The new spire, 151 meters (495 feet) tall, was not finally completed until 1882.[15] For a short time, from 1876 to 1880, the spire made Rouen Cathedral the world's tallest building, until the completion of Cologne Cathedral. 20th century In 1905, under the new law separating church and state, the Cathedral became the property of the French government, which then granted to the Catholic Church its exclusive use.[15] At the beginning of World War II in 1939, remembering the damage caused to French cathedrals in World War I, the Cathedral authorities protected the sculpture of the cathedral with sandbags and removed the old stained glass and transported it to sites far from the city. [15] Nonetheless, in the weeks before D-Day in Normandy, the cathedral was hit twice by Allied bombs. In April 1944, seven bombs dropped by the British Royal Air Force hit the building, narrowly missing a key pillar of the lantern tower, and damaging much of the south aisle and destroying two windows. In June 1944, a few days before D-Day, bombs dropped by the U.S. Army Air Force set fire to the Saint-Romain tower. The bells melted, leaving molten remains on the floor. Following World War II, a major restoration effort began to repair war damage by the Service of Historic Monuments, concluding in 1956. Then a new campaign began to consolidate the structure and to restore the statuary of the west front, including putting back four statues that had been moved elsewhere. In 2016, the project was finished and the scaffolding which had covered much of the cathedral for a half-century was finally removed.[16] Prior to the re-opening of the Cathedral in 1956, the choir, damaged by the bombing during the war, was given a substantial renewal. This included a new high altar topped by an 18th-century Rococo statue of Christ made of gilded made by Clodion, which had previously been on the altar screen, as well as new choir screens, a new episcopal throne, and a new communion table and pulpit made of cast iron and gilded copper.[17] Beginning in 1985, excavations were carried out beneath the church and its surroundings, which uncovered vestiges of the earlier Paleochristian buildings and foundations of the Carolingian cathedral.[16] In 1999, during Cyclone Lothar, a copper-clad wooden turret, which weighed 26 tons, broke free from the tower and fell partly into the church, damaging the choir. 21st centuryOn 11 July 2024, the central spire of the cathedral caught fire during renovation works.[18] The fire was brought under control the same day by a team of some 70 firefighters and 40 fire engines.[19] Timeline

ExteriorWest front

The west front of the Cathedral, with its three portals, is the traditional entrance to the Cathedral. The portals are aligned with the three aisles of the nave. The west front was first built in the 12th century, entirely redone in the 13th century, and then totally redone again at the end of the 14th century, each time become more lavishly decorated.[15] The main, or central portal, was originally dedicated to St. Romain in the 12th century, but was rededicated to the Virgin Mary when the facade was remade on a grander scale at the beginning of the 14th century. The central sculptural element of the tympanum, or arch over the portal, is a Tree of Jesse, a traditional depiction of the family tree of Christ. At the top is the Virgin Mary, with a halo of sun and stars. The arches above the tympanum of the portal are filled with sculpture of prophets, sibyls, or fortune-tellers, and patriarchs. The portals on either side of the central portal followed the same format, with sculpture in the tympanum vividly illustrating Biblical stories. The central portal, facing the building, is dedicated to John the Evangelist, and the sculpture in the tympanum above illustrates the baptism of Christ, the passage of Saint John; the dance of Salome; the feast of Herod; and the beheading of John the Baptist. The portal to the right is devoted to Saint Stephen, and its sculpture illustrates the gathering of souls, Christ in majesty, and the stoning of Stephen. The portal to the Traces of pigment and gilding on the sculpture indicate that all the sculpture was originally brightly colored. [21]

The towering buttresses on either side of the central portal were installed in the 14th century to strengthen the west front, and were covered with galleries of sculpture to merge them into the rest of the decoration. [15] Saint-Romain Tower

The Saint-Romain tower, on the left facing the west front, was begun in 1145 as part of the original Gothic cathedral. The top of the tower, more decorative, was added in the 15th century. Like the Butter tower on the right side, it is separated from and slightly behind the main block of the west front. The ground level has no windows, and contains the Baptistry. Above is a tall vaulted space with are four levels of bays, topped by a very ornate belfry. This contains the bourdon or largest Cathedral bell, named Joan of Arc, which weighs 9.5 tons. It also houses the sixty-four smaller bells of the carillon, which was restored in 2016. It is the second-largest carillon in France. The roof of the tower is decorated with sculptures of four small suns, made of gilded lead.[15] Butter Tower

The Butter Tower was constructed between 1488 and 1506, in a late Gothic Flamboyant style. It received its popular name because donors to the tower were given dispensation to consume butter and milk during Lent. The dense decoration of the tower emphasises its height; tall pointed niches for sculpture, buttresses decorated with tracery, pinnacles, gables and arches. At the top, the square plan of the tower becomes an octagon, with an ornate stone crown. A bell for the Butter Tower, named Georges d'Amboise in honor of the Cardinal, was completed in 1501. It cracked in 1786 and was melted down during the French Revolution.[22] Lantern tower and spire

A central lantern tower over the transept is a tradition of Gothic architecture in Normandy. [23] The lantern tower with its flèche, or spire is placed over the transept, almost in the centre of the cathedral, and is 151 meters high, the tallest of the three towers. The first two levels of the lantern tower were built in the 13th century. The original Gothic spire was destroyed by fire in 1514, and rebuilt in 1544 in wood and lead by the master builder Robert Becquet. The next builder, Rouland Le Roux, consolidated the first two levels of the lantern tower and added flamboyant decoration and sculpture.[24] Another fire in 1822 destroyed the lead and wood spire, which was then replaced, after much controversy, by the architect Jean-Antoine Alavoine with one of iron and copper, finished in 1882. He surrounded the new spire with four smaller spirelets, made of copper. One of these fell during a hurricane in 1999, going through the roof and damaging the choir stalls below.[24] On 11 July 2024, the main spire caught fire, though it was quickly brought under control.[25] Tourelles and sculpture galleries

In the 13th century four smaller towers, or tourelles, with spires, were added atop the buttresses that were built to support the west front, two on either side of the central portal below. In the 14th century, to enrich the decoration even further, three gables were attached to the west front below each of the tourelles. The gables were filled with sculpture; over the north portal, statues of the first archbishops, apostles and saints, and on the south, kings and prophets from the Old Testament. [26] The Nave exterior

Flying buttresses along the north and south sides of the cathedral reach up over the roof of the side aisles to support the upper walls of the nave. The space between the buttresses on the lower level is filled with lateral chapels. Because of the support of the buttresses, the upper walls of the nave are able to be entirely filled with windows. The edges of the roofs of the aisles and nave are both decorated with balustrades and pinnacles. North transept

Two portals, on the north and the south, heavily decorated, give access to the transept at the meeting point between the nave and the choir. On the north is the portail des librairies, and to the south the portail de la Calende. The north portal is similar in its plan to the north transept portal of Notre-Dame-de-Paris, built a few years earlier; the decoration of the portals spills over into the adjacent sections. Each portal has a column-statue between the doors, and is topped by a tympanum full of sculpture, and above that an arched voussure filled with three bands of statues. Above this a lace-like pointed gable, which rises upward in front of the windows of the claire-voie gallery as far as the rose window. A similar sculpted gable is placed over the rose window, just below the triangular gable of the transept roof. The embrasures of the doorway are also filled with delicate sculptural medallions. [24] South transept

The front of the south transept and the portal of La Calende are even more packed with sculpture and decoration. The scenes in the tympanum over the portal illustrate the life of Christ, while the contreforts on either side of the portals contain niches filled with angels and prophets The quadrille medallions around of the portal illustrate the Book of Genesis and are filled with an array of fantastic animals. Scenes of the Last Judgement fill the space over the tympanum. At the very top, over the rose window, is another gable filled with sculpture of the crowning of the Virgin Mary.[27] ChevetThe dominant feature of the Chevet, or east end of the Cathedral beyond the choir, is the chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary, which extends well east of the choir and apse. It has very high buttresses, topped by pinnacles containing statues, and high lancet windows topped by gables, which are topped with statues. Above all these is the 'Golden Virgin", a gilded statue of The Virgin Mary made by Nicolas Quesnel in 1541.[28] Smaller chapels, accessed by the disambulatory, are fit between the buttresses north and south of the Virgin Mary Chapel. In addition, the Sacristy and the Revestiaire are attached to the south side of chevet.[28]

InteriorPlan

Nave and collateral aisles

The nave is the portion of the cathedral where the churchgoers are seated, extending from the west front to the transept and choir. It is covered with four-part rib vaults, supported by colonettes with reach down the walls to the massive pillars on the ground floor. The first four traverses of the nave, on the west, completed by 1200, followed the original elevation plan of the late 13th century; an arcade of pillars on the ground floor, which opened into the collateral aisles; above that a tribune, or wide passageway; above that the triforium, a narrow passageway; and above that the clerestory, the high windows which reached up into the arches of the vaults. All these levels provided the necessary width to support the upper walls. [29] After the fire of 1200, the master builder Jean d'Andeli began to revise the plans, following the design used in High Gothic cathedrals, which had only three levels. He made a compromise; he preserved the tribunes but he installed a narrow coursiere or passageway atop the arches of the tribune, which wound around the pillars. He then made the arches of the tribune wider and taller, allowing more light from the windows of the collateral aisles to enter the nave. These modifications were possible thanks to another new technology, the flying buttress, which reaches over the collateral aisles to provide support to the upper nave walls, allowing them to be thinner and the windows to be larger.[29] The collateral aisles at Rouen are fourteen metres high compared with twenty-eight metres high vault in the nave. The high clerestory windows of the central nave look out over the roofs of the collateral aisles, and bring more light to the interior.[29] Transept

The transept is unusually large and brightly lit thanks to the large rose windows on the north and south and the large windows below them in the triforium of each transept. Overhead, the interior of the lantern tower is visible. The walls of the inside of the north and south facades are richly decorated with tracery, composed of pointed stone arches and sculpture in niches and in the small quadrille panels of the south transept. In the northwest corner is a stairway from 1471 which gave access to the cathedral library. It was updated with Neo-Gothic landings in the 18th century.[23] Choir

The Choir is the section of the cathedral at the east which was reserved for the clergy, and in the Middle Ages was separated from the nave by an elaborate screen. It was constructed slightly later than the nave, in the middle of the 13th century, and the style is more unified than in the nave. The beginning of the choir is marked by the retable of the main altar, and the throne of the Archbishop. Beyond that to the east are the stalls where the members of the clergy were seated.[30] The elevation of the Choir is different from that of the nave, being more in the High Gothic style of the 13th century, with three levels. The pillars of the arcade are circular, crowned with capitals decorated with stylised foliage and crochets. Above the arcade is the triforium, or enclosed gallery, and above that the high windows, which form a half-circle.[30] The center of the Choir was substantially refurbished before the 1956 re-opening to repair damage suffered during the war. The high altar was added, topped by an 18th-century Rococo statue of Christ made of gilded lead made by Clodion, which had previously been part of the 18th-century altar screen, as well as two kneeling angels, made by Caffieri in 1766, and previously in the Church of Saint-Vincent de Rouen, which was destroyed in 1944. The Choir also received modern screens by 20th-century artist Raymond Subes, a new episcopal throne, and a modern communion table and pulpit made of cast iron and gilded copper.[17][ Choir stalls

The Choir stalls were put in place between 1457 and 1470 by the master woodworker Philipott Viart. A majority of the original seats are still in place, along with the carved decorations, called misericords, illustrating scenes from the Bible, as well as proverbs, fables and craftsmen at work. Unfortunately, the upper portions of the stalls were destroyed during the Revolution.[31] Tombs of the Dukes of Normandy

The remains of four Dukes of Normandy are placed in the simple tombs with their images on either side of the choir. These are the tombs of Rollo, a Viking and the first Duke of Normandy; William Longsword, the son of Rollo (died 942); Henry the Young King (died 1183); and a tomb with the heart of Richard the Lionheart, Duke of Normandy and King of England (died 1199); his body was buried at Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou. The original tomb of Rollo was destroyed during the bombing of 1944, and was replaced by a copy of the tomb of Henry the Young King made in the 19th century. The remains of Rollo and his son William Longsword were transferred from the first cathedral to the Romanesque cathedral in 1063, shortly after it was built, then to the Gothic cathedral when it was completed.[32] Collateral Chapels

Eighteen small chapels are placed between the buttresses on the north and south sides of the nave. They are filled with art, sculpture and stained glass given by wealthy donors and the guilds of the city. Some of the chapels are very plain, while others are adorned with paintings and sculptures from the 17th and 18th centuries. The Chapel of Sainte-Catherine is distinguished by its highly ornate lambris with painted panels of the life of Saint Brice. The bombardment of the Catedral in 1944 destroyed the other five chapels on the south side of the nave; only the Chapel of Sainte-Catherine survived intact. [33] Apse – The Chapel of the VirginAt the east end of the cathedral is the Chapel of the Virgin, dedicated to the Virgin Mary. It was constructed by master builder Jean Davi beginning in 1302, when the veneration of the Virgin began to play a larger role in Christian theology, and replaced a more modest earlier chapel. Following the style of the 14th century, the windows fill the entire upper portion of the walls, while the lower walls are covered with elaborate tracery and sculpture. Traces of gilding and pigment on the walls show that the chapel was originally brightly colored.[34] The central feature of the chapel is an enormous altar, made in the 17th century, framing a painting of the Virgin surrounded by carved and sculptural decoration. The chapel also contains the tomb of Cardinal Georges d'Amboise, the principal patron of the Gothic cathedral, and his nephew and successor, Cardinal Georges II d'Amboise. It is placed against the south wall. The nephew, Georges II, moved the statue of his uncle to the side of the tomb and placed his own in the central position. The baldaquin or upper portion of the tomb is lavishly decorated with sculpture of the Apostles, in pairs, separated by Sibyls and Biblical kings. The top of the tomb is ornamented with sculpted candelabra and tempietti. or miniature classical temples. The other monumental tomb in the chapel is that of Louis and Pierre de Brézé, made between 1536 and 1541 in a purely Renaissance style. Louis, who died in 1531, was the grandson of Pierre, and was Senechal and Governor of Normandy. His wife was Diane de Poitiers, who was the mistress of King Henri II of France; it was she who commissioned the tomb. Its main elements are a triumphal arch, under which Louis, in armor and on horseback, is passing in triumph. He appears again at the bottom as a corpse, almost nude. Diane is depicted next to his corpse, kneeling. The tomb is attributed to the prominent French Renaissance sculptor Jean Goujon, who was active during this period as a sculptor to Henri II. [34]

Stained glassA considerable portion of the original stained glass from the 13th century is still in place. It dates from about the same time as the early windows of Chartres Cathedral and Bourges Cathedral. There are five bays with windows of early glass found in the collateral chapels of the north nave. The early windows are composed of series of medallions arranged in rows. Each medallion is made of small pieces of thick glass, deeply colored, particularly in reds and blues, bound together like mosaics with thin strips of lead. 13th-century windows

The collateral chapels on the north side of the nave have some of the oldest existing windows. Some of these windows were funded by the guilds of craftsmen, and depict them at their work. Unusually, some of the windows, such as the Window of saint Joseph, are signed by the glass artist; the band in front of the Saint reads: "Clement, glassmaker of Chartres".[35] The "Belles Verrieres"

The "Belles Verrieres" are a group of windows located in the collateral chapels on the north side of nave and in the transept, containing some of the earliest stained glass in the cathedral. They are composed of early 13th century glass that was moved in the 15th century from its original locations in the south collateral chapels and reinstalled into new windows in the Chapel Saint-Jean, Chapel Saint-Severus, the Chapel of the Saint-Sacrament, and the Chapel of Saint-Pierre-and-Saint-Paul. The window in Bay 53 of the Chapel of Saint-Joseph-de-la-nef shows some of the craftsmen planning and building Rouen cathedral. 14th–15th century windows

The windows of the 14th century began to look considerably different than the earlier windows. Glass artists had begun using techniques of silver stain and enamel paints baked on the glass to add greater detail and realism to the images. The windows looked less like mosaics, and increasingly resembled paintings, with the use of perspective and shading to suggest three dimensions. Fourteenth-century windows often depicted the subjects, usually saints and bishops, in architectural settings, surrounded and crowned by elaborate canopies and arches, to match the architecture of the cathedral. They also made greater use of grisaille, or a greyish or white glass, which surrounded and set off the figures and also brought increased light into the cathedral. [36] One example from the mid-14th century is the Pentecost window in Bay 36, with an edge of grisaille bordered by angel musicians.[37] Rose windows (15th c.)

The rose window of the north portal is the only large rose window to survive in its original form. It was made by Guillaume Nouel at the end of the 14th century, and depicts Christ surrounded by the evangelists, bishops, kings and martyrs.[38] Renaissance windows (16th century)

The windows of the 16th century most fully display the influence of the Renaissance, with greater realism and closer resemblance to paintings. A good example is the window in the Chapel of Saint-Joseph, in the south transept. While it is full of activity and detail, it lacks some of the depth and richness of color given by the thick, densely-coloured glass of the 13th-century windows.[36] Other major 16th-century works are two windows of the Saint-Romain chapel, the south part of the nave next to the transept. These are based on the work of the Rouen painter Arnoult de Nimegue or his followers. They depict scenes from the life of the archbishop Romaine, best known in Rouen legends for ridding the city of a monster called "The Gargoyle".[37] Modern windows (20th century)

The Cathedral has a number of modern windows created in the 1950s to replace windows which were destroyed in the bombardments of the Second World War. They resemble, in their colors and the density of their imagery, the earlier medieval and Renaissance windows. One example is found in the Chapel of St. Leonard, Bay 50. Other striking examples are the three Joan of Arc windows in the Chapel of Joan-of-Arc in the South transept, bays 22, 24 and 26. These were made in 1955–56.[37] BellsThe cathedral has seventy bells made by the Fonderie Paccard in Annecy. There are sixty-four in the Saint-Romain Tower and six in the Butter Tower.[39] Together they are the heaviest "peal" or group of bells in France, with a combined weight of thirty-six tons.[40] Grand Organ

The cathedral had an organ since the 1380s. A larger new organ was constructed beginning in 1488, and placed at the beginning of the nave, on the inside of the west front under the rose window. This organ was damaged in the hurricane of 1683, but was put back into service. Prominent organists included Jean Titelouze from 1588 until 1634, and Jacques Boyvin from 1674 until 1706. A smaller organ had been installed in the choir in 1517, in the center of the Choir screen, removed during the Renaissance. [41] New organs were built by Merklin & Schütze (1858–60) and, after World War II, by Jacquot-Lavergne. Treasury

The treasury of the Cathedral was originally in the Sacristy, and then was moved to its own tower on the Alban Courtyard, on the north side of the cathedral. It was twice pillaged; first by the Protestants in 1562, then during the French Revolution in 1791. Most of the original objects were lost, with the exception of the Chasse de Saint-Roman, but in the 19th century, a new collection was assembled, acquired from monasteries, churches and private collections. Notable objects include the Châsse de Saint Roman, a miniature cathedral made of gilded copper, with figures of Christ and the Apostles (late 13th century); the Châsse de Notre Dame, a mini-cathedral of gilded bronze and enamel, devoted to the Virgin Mary (19th century); A 15th-century monstrance, an elaborate miniature tower embracing a crystal cylinder used to hold the host during the Eucharist ceremony; and the Ostentoire of Two Crowns (1777), a similar vessel for the host, decorated with a gilded crown and rays of light. The treasury also displays some of the elaborate ceremonial costumes worn by the Archbishops. [42] Crypt

The 11th-century crypt of the original Romanesque cathedral is located underneath the choir of the Gothic cathedral. It is accessed through the Chapel of Saint Joan of Arc on the south side of the Choir. It was excavated between 1931 and 1934, and opened to visitors in 1956. It was within the foundation of the old cathedral, and is composed of a sanctuary and a curving ambulatory with three small chapels, with vaults supported by two rows of columns. The original floor was made of a pattern of light stone and black marble. There is a well located in the ambulatory, beneath the axis of the apse above. [43] The Cathedral in art and literatureThe most famous paintings of the cathedral were done by the Impressionist artist Claude Monet, who produced a series of paintings of the building showing the same scene at different times of the day and in different weather conditions. Two paintings are in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; one is in the Getty Center in Los Angeles; one is in the National Museum of Serbia in Belgrade; one is at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts; one is in a museum of Cologne; one is in the Rouen fine art museum; and five are in the musée d'Orsay in Paris. The estimated value of one painting is over $40 million.

Other painters inspired by the building included John Ruskin, who selected it as an example of good architecture in The Seven Lamps of Architecture, and Roy Lichtenstein, who produced a series of pictures representing the cathedral's front. Mae Babitz, known for illustrations of the Watts Towers and Victorian-era buildings in Los Angeles, illustrated the Cathedral in the 1960s. Those works are held in the UCLA library Special Collections. In literature, Gustave Flaubert was inspired by the stained glass windows of St. Julian and the bas-relief of Salome, and based two of his Three Tales on them. Joris-Karl Huysmans wrote La Cathédrale, a novel based on an intensive examination of the building. Willa Cather sets a key scene in the development of the protagonist Claude Wheeler of One of Ours in the cathedral. BurialsThe Cathedral houses a tomb containing the heart of Richard the Lionheart. His bowels were probably buried within the church of the Château of Châlus-Chabrol in the Limousin. It was from the walls of the Château of Châlus-Chabrol that the crossbow bolt was fired, which led to his death once the wound became septic. His corporeal remains were buried next to his father at Fontevraud Abbey near Chinon and Saumur, France. Richard's effigy is on top of the tomb, and his name is inscribed in Latin on the side. The Cathedral also contains the tomb of Rollo (Hrólfr, Rou(f) or Robert), one of Richard's ancestors, the founder and first ruler of the Viking principality in what soon became known as Normandy. The cathedral contained the black marble tomb of John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford, one of the English commanders who oversaw Joan of Arc's trial. His original tomb was destroyed by the Calvinists in the 16th century but there remains a commemorative plaque. Other burials include:

Dimensions

See also

References

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Rouen Cathedral. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||