|

Seneca language

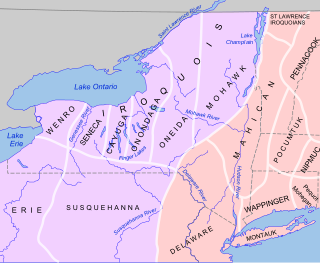

Seneca (/ˈsɛnəkə/;[2] in Seneca, Onöndowaʼga꞉ʼ Gawë꞉noʼ, or Onötowáʼka꞉) is the language of the Seneca people, one of the Six Nations of the Hodinöhsö꞉niʼ (Iroquois League); it is an Iroquoian language, spoken at the time of contact in the western part of New York.[3] While the name Seneca, attested as early as the seventeenth century, is of obscure origins, the endonym Onödowáʼga꞉ translates to "those of the big hill."[3] About 10,000 Seneca live in the United States and Canada, primarily on reservations in western New York, with others living in Oklahoma and near Brantford, Ontario. As of 2022, an active language revitalization program is underway.[4] Classification and historySeneca is an Iroquoian language spoken by the Seneca people, one of the members of the Iroquois Five (later, Six) Nations confederacy.[5] It is most closely related to the other Five Nations Iroquoian languages, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk (and among those, it is most closely related to Cayuga).[3] Seneca is first attested in two damaged dictionaries produced by the French Jesuit missionary Julien Garnier around the turn of the eighteenth century. It is clear from these documents, and from early nineteenth century Seneca writings, that the eighteenth century saw an extremely high degree of phonological change, such that the Seneca collected by Garnier would likely be mutually unintelligible with modern Seneca.[6] Moreover, as these sound changes appear to be unique to Seneca, they have had the effect of making Seneca highly phonologically divergent from the languages most closely related to it, as well as making the underlying morphological richness of the language incredibly opaque.[7] Today, Seneca is spoken primarily in western New York, on three reservations, Allegany (ʼohi꞉yoʼ), Cattaraugus (kaʼtä꞉kë̓skë꞉öʼ), and Tonawanda (tha꞉nöwöteʼ), and in Ontario, on the Grand River Six Nations Reserve (swe꞉këʼ).[3][5] While the speech community has dwindled to approximately one hundred native speakers, revitalization efforts are underway. Language revitalization In 1998, the Seneca Faithkeepers School was founded as a five-day-a week school to teach children the Seneca language and tradition.[8] The School has published language learning tools and courses on the language-learning platform Memrise broken out by topic.[9] In 2010, K-5 Seneca language teacher Anne Tahamont received recognition for her work with students at Silver Creek School and in language documentation, presenting "Documenting the Seneca Language' using a Recursive Bilingual Education Framework" at the International Conference on Language Documentation and Conservation (ICLDC).[10] As of summer 2012,

The project will develop "a user-friendly, web-based dictionary or guide to the Seneca language."[12] "Robbie Jimerson, a graduate student in RIT's computer science program and resident of the Cattaraugus Indian Reservation near Buffalo," who is working on the project, commented: "My grandfather has always said that a joke is funnier in Seneca than it is in English."[13] As of January 2013, a Seneca language app was under development.[14] As of fall 2012, Seneca language learners are partnering with fluent mentors, and a newsletter, Gae꞉wanöhgeʼ! Seneca Language Newsletter, is available online.[15] Although former Seneca-owned radio station WGWE (whose call sign derives from "gwe," a Seneca word roughly translating to "what's up?") broadcast primarily in English, it featured a daily "Seneca Word of the Day" feature before each noon newscast, broadcast a limited amount of Seneca-language music, and made occasional use of the Seneca language in its broadcasts in a general effort to increase awareness of the Seneca language by the general public. In 2013, the first public sports event was held in the Seneca language, when middle school students served as announcers for a lacrosse match.[16] Bilingual road signs, such as stop signs and speed limit signs, appear in the Seneca capital of Jimersontown; these signs were erected in 2016. Prior to this, as part of the upgrade to Interstate 86, the names of townships within the Allegany Indian Reservation were marked in Seneca along the highway in Comic Sans. PhonologySeneca words are written with 13 letters, three of which can be umlauted, plus the letter colon (꞉) and the acute accent mark. Seneca language is generally written in all-lowercase, and capital letters are only used rarely, even then only for the first letter of a word; all-caps is never used, even on road signs. The vowels and consonants are a, ä, e, ë, i, o, ö, h, j, k, n, s, t, w, y, and ʼ.[17][18] In some transliterations, t is replaced by d, and likewise k by g; Seneca does not have a phonemic differentiation between voiced and voiceless consonants (see below in Phonology 2.1: Consonants). The letter j can also be replaced by the three-letter combination tsy. (For example, a creek in the town of Coldspring, New York, and the community near it, bears a name that can be transliterated as either jo꞉negano꞉h or tsyo꞉nekano꞉h.) ConsonantsAs per Wallace Chafe's 2015 grammar of Seneca, the consonantal and non-vocalic inventory of Seneca is as follows.[19] Note that orthographic representations of these sounds are given in angled brackets where different from the IPA transcription.

Resonants j is a palatal semivowel. After [s], it is voiceless and spirantized [ç]. After [h], it is voiceless [j̊], in free variation with a spirant allophone [ç]. After [t] or [k], it is voiced and optionally spirantized [j], in free variation with a spirant allophone [ʝ]. Otherwise it is voiced and not spirantized [j]. /w/ is a velar semivowel. It is weakly rounded [w]. /n/ is a released apico-alveolar nasal [n̺].[20] Obstruents/t/ is an apico-alveolar stop [t̺]. It is voiceless and aspirated [t̺ʰ] before an obstruent or an open juncture (but is hardly audible between a nasalized vowel and open juncture). It is voiced and released [d̺] before a vowel and resonant. /k/ is a dorso-velar stop [k]. It is voiceless and aspirated [kʰ] before an obstruent or open juncture. It is voiced and released [g] before a vowel or resonant. /s/ is a spirant with blade-alveolar groove articulation [s]. It is always voiceless, and is fortified to [s˰][clarification needed] everywhere except between vowels. It is palatalized to [ʃ] before [j],[clarification needed] and lenited to [s˯][clarification needed] intervocalically.[20] /dʒ/ is a voiced postalveolar affricate [dʒ], and /dz/ is a voiced alveolar affricate [dz]. Before [i], it is optionally palatalized [dz] in free variation with [d͡ʑ].[clarification needed][7] Nevertheless, among younger speakers, it appears as though /dʒ/ and /dz/ are in the process of merging to [dʒ].[21] Similarly, /tʃ/ is a voiceless postalveolar affricate [tʃ], and /ts/ is a voiceless alveolar affricate [ts].[21] Laryngeal obstruents/h/ is a voiceless segment [h] colored[clarification needed] by an immediately preceding and/or following vowel and/or resonant. /ʔ/ is a glottal stop [ʔ], written ⟨ʼ⟩ and commonly substituted with ASCII ⟨´⟩.[7] VowelsThe vowels can be subclassified into the oral vowels /i/, /e/, /æ/, /a/, and /o/, and the nasalized vowels /ɛ/ and /ɔ/. Of these vowels, /æ/ is relatively rare, an innovation not shared with other Five Nations Iroquoian languages; even rarer is /u/, a vowel only used to describe unusually small objects.[20][22] Note that orthographic representations of these sounds are given in angled brackets where different from the IPA transcription.

The orthography described here is the one used by the Seneca Bilingual Education Project. The nasal vowels, /ɛ̃/ and /ɔ̃/, are transcribed with tremas on top: ⟨ë ö⟩. Depending on the phonetic environment, the nasal vowel ⟨ë⟩ may vary between [ɛ̃] and [œ̃], whereas ⟨ö⟩ may vary from [ɔ̃] to [ɑ̃].[22] Long vowels are indicated with a following ⟨:⟩, while stress is indicated with an acute accent over the top. æ is transcribed as ä.[23] Oral vowels/i/ is a high front vowel [i]. /e/ is a high-mid front vowel. Its high allophone [ɪ] occurs in postconsonantal position before [i] or an oral obstruent. Its low allophone [e] occurs in all other environments. /æ/ is a low front vowel [æ]. /a/ is a low central vowel. Its high allophone [ʌ] occurs in postconsonantal position before [i], [w], [j], or an oral obstruent. Its low allophone [ɑ] occurs in all other environments. Before [ɛ] or [ɔ] it is nasalized [æ].[clarification needed] /o/ is a mid back vowel. It is weakly rounded. Its high allophone [ʊ] occurs in postconsonantal position before [i] or an oral obstruent. Its low allophone [o] occurs in all other environments.[20] /u/ is a rounded high back vowel [u]. It has also, however, been recorded as [ɯ].[21] Nasal vowels/ɛ/ is a low-mid front vowel. It is nasalized [ɛ̃]. /ɔ/ is a low back vowel. It is weakly rounded and nasalized [ɔ̃].[20] DiphthongsThe following oral diphthongs occur in Seneca: ae, ai, ao, ea, ei, eo, oa, oe, and oi. The following nasal diphthongs occur as well: aö, eö, and oë.[clarification needed][24] ProsodyVowel length is marked with a colon ⟨꞉⟩, and open juncture by word space.[25] Long vowels generally occur in one of two environments: 1. In even-numbered (i.e. falling and even number of syllables from the beginning of the word) word-penultimate syllables not followed by a laryngeal stop; and 2. In odd-numbered penultimate syllables that A. are followed by only one non-vocalic segment before the succeeding vowel, B. are not followed by a laryngeal stop, and C. do not contain the vowel [a] (unless the syllable is word-initial). Moreover, vowels are often lengthened compensitorally as the reflex of a short vowel and an (elided) glottal segment (e.g. vowels are long preceding glottal fricatives elided before sonorants (*V̆hR > V̄R)).[26] Stress is either strong, marked with an acute accent mark (e.g. ⟨é⟩), or weak, which is unmarked (e.g. ⟨e⟩).[25] Seneca accented short vowels are typically higher in pitch than their unaccented counterparts, while accented long vowels have been recorded as having a falling pitch. Short vowels are typically accented in a trochaic pattern, when they appear in even-numbered syllables preceding A. a laryngeal obstruent, B. a cluster of non-vocalic segments, or C. an odd-numbered syllable containing either A or B. There does not appear to be any upper or lower limit on how many such syllables can be accented – every even-numbered syllable in a word can be accented, but none need be accented. Syllables can also be stressed by means of accent spreading, if an unaccented vowel is followed immediately by a stressed vowel (i.e. VV́ > V́V́). Additionally, word-initial and word-final syllables are underlyingly unaccented, although they can be given sentence level stress.[27] Syllable structureSeneca allows both open and closed syllables; a Seneca syllable is considered to be closed when the nucleus is followed by a cluster of multiple consonants. Moreover, [h] appears to be ambisyllabic intervocalically, and can be included in a cluster of multiple non-consonantal segments in the onset.[27] MorphologySeneca is a polysynthetic, agglutinative language with a remarkably rich verbal morphological system, and to a lesser extent, a fairly rich system of nominal morphology as well. Verbs constitute a decisive majority of Seneca words (by one estimate, as much as eighty-five percent of different words),[28] and between the numerous classes of morphemes that can be added to the verb root, the generally multiple morphemes constituent thereto, and the variants thereof, a truly staggering number of Seneca verbs is grammatically possible. While most verb forms have multiple allomorphs, however, in the majority of cases, variants of morphemes cannot be reliably predicted on the basis of its phonological environment. Verbal morphologyComposition of the verb baseThe verb base can be augmented by adding a derivational suffix, a middle voice or reflexive prefix, or an incorporated noun root. The common middle voice prefix describes actions performed by an agent and received by that same agent. Its forms, in descending order or prevalence, are as follows:[29]

The similar reflexive prefix is nearly semantically identical, the only difference being that the reflexive prefix more clearly distinguishes the two (unitary) roles of agent and recipient. Its forms are not regularly predictable by phonetic environment, and are derived from the underlying form -at-. A noun can be incorporated into the verb base by placing it before the middle voice or reflexive prefix (i.e. at the front of the base noun), such that that noun becomes the patient (or often, instrument or manner) of the verb. In between noun-final and prefix/verb root-initial consonants, the "stem-joining" vowel -a- is epenthesized. The following types of derivational suffixes can be added at the end of a base noun to alter the meaning of the verb; these are as follows (given with the underlying form or most common form of the suffix):

Aspect suffixesSeneca verbs consist of a verb base that represents a certain event or state, which always includes a verb root; this is always followed by an aspect suffix, and almost always preceded by a pronominal prefix. Pronominal prefixes can describe an agent, a patient, or the object of the verb, while aspect suffixes can be habitual or stative, describing four types of meanings: habitual, progressive, stative, and perfect. Bases are classified as "consequential" or "nonconsequential," on the basis of whether or not they "result in a new state of affairs." Nonconsequential bases use habitual aspect suffixes to describe habitual actions, and stative aspect stems to describe progressive actions. Consequential bases use habitual aspect suffixes to describe habitual or progressive actions, and stative aspect stems to describe perfect actions. Some verb roots are said to be stative-only; these typically describe long states (e.g. "to be heavy," "to be old," etc.). Habitual and stative roots are related to the ending of the verb base, but have become largely arbitrary, or at least inconsistent. Additionally, there is a common punctual suffix, an aspect suffix that is added to describe punctual events. It necessarily takes the "modal prefix," which precedes a pronominal prefix, and indicate the relationship of the action described in the verb to reality; these three prefixes are factual, future, and hypothetical. A list of forms of each of the stems is as follows:[30]

Pronominal morphologyThe system of pronominal prefixes attached to Seneca verbs is incredibly rich, as each pronoun accounts not only for the agent of an action, but for the recipient of that action (i.e. "patient") as well. For example, the first person singular prefix is k- ~ ke- when there is no patient involved, but kö- ~ köy- when the patient is 2sg, kni- ~ kn- ~ ky- when the patient is 2du., and kwa- ~ kwë- ~ kw- ~ ky- when the patient is 2pl. There are fifty-five possible pronominal pronouns, depending on who is performing an action, and who is receiving that action. These pronouns express number as singular, dual, or plural; moreover, in the case of pronominal prefixes describing agents, there is an inclusive/exclusive distinction in the first person. Gender and animacy are expressed as well in the third person; gender distinctions are made between masculine entities and "feminine-zoic" entities (i.e. women and animals), and inanimacy is distinguished in singular forms. Moreover, before pronominal prefixes, "preproniminal" prefixes carrying a variety of meanings can be placed to modify the meaning of the verb. The prefixes, in the order in which the precede one another, are as follows:[31]

Nominal morphologySeneca nominal morphology is far simpler than verbal morphology. Nouns consist of a noun root followed by a noun suffix and a pronominal prefix. The noun suffix appears as either a simple noun suffix (denoting, naturally, that it is a noun), an external locative suffix, denoting that something is "on" or "at" that noun, or an internal locative suffix, denoting that something is "in" that noun. The forms of these are as follows:[32] - Simple noun suffix: -aʼ ~ -öʼ (in a nasalizing context) - External locative suffix: -aʼgeh - Internal locative suffix: -aʼgöh Nouns are often preceded by pronominal prefixes, but in this context, they represent possession, as opposed to agency or reception. Nouns without pronominal prefixes are preceded by either the neuter patient prefix yo- ~ yaw- ~ ya-, or the neuter agent prefix ka- ~ kë- ~ w- ~ y-. These morphemes do not hold semantic value, and are historically linked to certain noun roots arbitrarily. Finally, certain prepronominal verbal prefixes can be suffixed to nouns to alter the meaning thereof; in particular, the cislocative, coincident, negative, partitive, and repetitive fall into this group. SyntaxAs much of what, in other languages, might be included in a clause is included in the Seneca word, Seneca features free word order, and cannot be neatly categorized along the lines of a subject/object/verb framework. Rather, new information appears first in the Seneca sentence; when a noun is judged by the speaker to be more "newsworthy" than a verb in the same sentence, it is likely to appear before the verb; should it not be deemed to hold such relevance, it typically follows the verb.[33] Particles, the only Seneca words that cannot be classified as nouns or verbs,[28] appear to follow the same ordering paradigm. Moreover, given the agent/participant distinction that determines the forms of pronominal morphemes, it seems appropriate to consider Seneca a nominative-accusative language.[31] CoordinationIn Seneca, multiple constituents of a sentence can be conjoined, in a number of ways. They are summarized as follows:[34]

DeixisThe words utilized in Seneca to identify referents based on their position in time and space are characterized by a proximal/distal distinction, as seen in the following demonstrative pronouns:[35]

Sample texts"Funny Story"As translated by Nils M. Holmer.[36] Note: for clarity, certain graphemes employed by Mr. Holmer have been replaced with their modern, standard equivalents. hatinöhsutkyöʼ They-had-a-house-it-is-said yatatateʼ they-are-grandfather-and-grandson wayatuwethaʼkyöʼ. they-went-hunting-it-is-said. tyëkwahkyöʼshö All-of-a-sudden-they-say katyeʼ it-flies citeʼö a-bird hukwa nearby uswëʼtut it-hollow-tree katyeʼ then-it-is-said nekyöʼ here nehuh it-went-into. hösakayöʼ. In-just-a-little-while tatyöʼkyöʼshö it-flies katyeʼ just-a-little-while tötakayakëʼt. it-flew-again. tatyöʼkyöʼshö In-just-a-little-while skatyeʼ it-flew-again hösakayöʼ. it-went-in. tatyöʼshö In-just-a-little-while katyeʼ it-flies tötakayakëʼt. it-came-out-again. A grandfather and a grandson had a house, it is said; they went hunting. All of a sudden a bird came flying (from) near a hollow tree; then, it is said, it flew into it. After a little while it flew in again. After a little while, it flew back (into the hollow tree). After a while it came flying out again, etc. "The Burning of Pittsburgh"As translated by Nils M. Holmer; unfortunately, the story is not preserved completely.[37] Note: for clarity, certain graphemes employed by Mr. Holmer have been replaced with their modern, standard equivalents. wae Therefore, neʼkyöʼ so-it-is-said nökweʼöweh the-Indians ëötinötëʼtaʼ they-will-burn-the-city työtekëʼ Pittsburgh skat four tewënyaʼe hundred kei (corrected: wis) four niwashë tens keiskai and-one nyushake years nyuweʼ. ago. wäönöhtakuʼkeʼö They-failed-it-is-said a꞉tinötëʼtaʼ that-they-burn-the-city neʼkeʼö. so-it-is-said. tyuhateisyöʼkeʼö Fallen-timber-it-is-said tkayasöh where-it-is-called waatinötayë꞉. they-camped. kanyuʼkeʼö When-it-is-said wäönöhtakuʼ they-failed a꞉tyueʼtaʼ that-they-burn kanötayë꞉ʼ the-city tanëh then tethönöhtëtyöʼ. they-went-back. tanë(h) Then hatyunyaʼtak (?) they-used-to-tell catek Kanöhka'itawi'-it-is-said ne what-they-tried-to-do hënökweʼöweh. the-Indians. thönöëcatek There-they-used-to-own-land ne the hënökweʼöweh. Indians. tekyöʼ Eight tyushiyaköh (?) years-old kanöhkaʼitawiʼ. Kanöhka'itawi' cyäöwauwiʼ When-they-told-him nuytiyenöweʼöh what-they-tried-to-do hënökweʼöweh the-Indians ... ... Therefore, it is said, the Indians intended to burn (the city of) Pittsburgh one-hundred-and-forty (fifty) -four years ago. They failed to burn the city, so it is told. At the place which is called Fallen Timber, there they camped. When they failed to burn the city they returned (to the camp). Then they used to tell a boy, whose name was Kanöhka'itawi', of what they tried to do. The Indians used to own the land (they would tell him). Eight years old was Kanöhka'itawi'. When they told him what the Indians tried to do ... (the story was not finished). See also

Notes

References

Further reading

External links |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||