|

Southwark

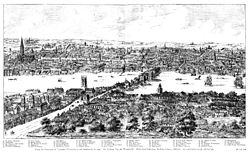

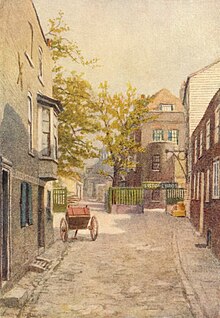

Southwark (/ˈsʌðərk/ ⓘ SUDH-ərk)[1] is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed due to its position at the southern end of the early versions of London Bridge, for centuries the only dry crossing on the river. Around 43 AD, engineers of the Roman Empire found the geographic features of the south bank here suitable for the placement and construction of the first bridge. London's historic core, the City of London, lay north of the bridge and for centuries the area of Southwark just south of the bridge was partially governed by the City, while other areas of the district were more loosely governed. The section known as Liberty of the Clink became a place of entertainment. By the 12th century Southwark had been incorporated as an ancient borough, and this historic status is reflected in the alternative name of the area, as Borough. The ancient borough of Southwark's river frontage extended from the modern borough boundary, just to the west of the Oxo Tower, to St Saviour's Dock (originally the mouth of the River Neckinger) in the east. In the 16th century, parts of Southwark near London Bridge became a formal City ward, Bridge Without. The urban area expanded over the years and Southwark was completely separated administratively from the City in 1900. Local points of interest include Southwark Cathedral, Borough Market, Shakespeare's Globe theatre, The Shard, Tower Bridge, Butler's Wharf and the Tate Modern museum. HistoryToponymyThe name Suthriganaweorc[2] or Suthringa geweorche[3] is recorded for the area in the 10th-century Anglo-Saxon document known as the Burghal Hidage[3] and means "fort of the men of Surrey"[2] or "the defensive work of the men of Surrey".[3] Southwark is recorded in the 1086 Domesday Book as Sudweca. The name means "southern defensive work" and is formed from the Old English sūþ (south) and weorc (work). The southern location is in reference to the City of London to the north, Southwark being at the southern end of London Bridge. In Old English, Surrey means "southern district (or the men of the southern district)",[4] so the change from "southern district work" to the latter "southern work" may be an evolution based on the elision of the single syllable ge element, meaning district. Rome   Recent excavation has revealed pre-Roman activity including evidence of early ploughing, burial mounds and ritual activity. The natural geography of Southwark (now much altered by human activity), was the principal determining factor for the location of London Bridge, and therefore London itself. Natural settingUntil relatively recent times, the Thames in central London was much wider and shallower at high tide. The natural shoreline of the City Of London was a short distance further back than it is now, and the high tide shoreline on the Southwark side was much further back, except for the area around London Bridge. Southwark was mostly made up of a series of often marshy tidal islands in the Thames, with some of the waterways between these island formed by branches of the River Neckinger, a tributary of the Thames. A narrow strip of higher firmer ground ran on a N-S alignment and, even at high tide, provided a much narrower stretch of water, enabling the Romans to bridge the river. As the lowest bridging point of the Thames in Roman Britain, it determined the position of Londinium; without London Bridge there is unlikely to have been a settlement of any importance in the area; previously the main crossing had been a ford near Vauxhall Bridge. Because of the bridge and the establishment of London, the Romans routed two Roman roads into Southwark: Stane Street and Watling Street which met in what in what is now Borough High Street. For centuries London Bridge was the only Thames bridge in the area, until a bridge was built upstream more than 10 miles (16 km) to the west.[note 1] Archaeological findsIn February 2022, archaeologists from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) announced the discovery of a well-preserved massive Roman mosaic which is believed to date from A.D. 175–225. The dining room (triclinium) mosaic was patterned with knot patterns known as the Solomon's knot and dark red and blue floral and geometric shapes known as guilloche.[5][6][7][8] Archaeological work at Tabard Street in 2004 discovered a plaque with the earliest reference to 'Londoners' from the Roman period on it. End of Roman SouthwarkLondinium was abandoned at the end of the Roman occupation in the early 5th century and both the city and its bridge collapsed in decay. The settlement at Southwark, like the main settlement of London to the north of the bridge, had been more or less abandoned, a little earlier, by the end of the fourth century.[9] Saxons and VikingsKing Alfred the GreatSouthwark appears to recover only during the time of King Alfred and his successors. Sometime about 886, the burh of Southwark was created and the Roman city area reoccupied. It was probably fortified to defend the bridge and hence the reemerging City of London to the north. St OlafThis defensive role is highlighted by the role of the bridge in the 1014-1016 war between King Ethelred the Unready and his ally Olaf II Haraldsson (later King of Norway, and afterwards known as St Olaf, or St Olave) on one side, and Sweyn Forkbeard and his son Cnut (later King Cnut), on the other. London submitted to Swein in 1014, but on Swein's death, Ethelred returned, with Olaf in support. Swein had fortified London and the bridge, but according to Snorri Sturleson's saga, Edgar and Olaf tied ropes from the bridge's supporting posts and pulled it into the river, together with the Danish army, allowing Ethelred to recapture London.[10] This may be the origin of the nursery rhyme "London Bridge Is Falling Down".[11] There was a church, St Olave's Church, dedicated to St Olaf before the Norman Conquest and this survived until the 1920's. St Olaf House (part of London Bridge Hospital), named after the church and its saint, stands on the spot. Tooley Street, being a corruption of St Olave's Street, also takes its name from the former church.[12] King CanuteCnut returned in 1016, but capturing the city was a great challenge. To cut London off from upstream riverborne supplies, Cnut dug a trench around Southwark, so that he could sail or drag his ships around Southwark and get upstream in a way that allowed his boats to avoid the heavily defended London Bridge.[13] In so doing he hoped to cut London off from river borne resupply from upstream. The Dane's efforts to recapture London were in vain, until he defeated Ethelred at the Battle of Assandun in Essex later that year, and became King of England. It is thought that the section of the Kent Road, at Lock Bridge, was Canute's Trench.[14] In May, 1016,[15] In 1173, a channel following a similar course was used to drain the Thames to allowing building work on London Bridge.[16]  Later medieval periodSouthwark and in particular the Bridge, proved a formidable obstacle against William the Conqueror in 1066. He failed to force the bridge during the Norman conquest of England, but Southwark was devastated.[17] At Domesday, the area's assets were: Bishop Odo of Bayeux held the monastery[18] (the site of modern Southwark Cathedral) and the tideway, which still exists as St Mary Overie dock; the King owned the church (probably St Olave's) and its tidal stream (St Olave's Dock); the dues of the waterway or mooring place were shared between King William I and Earl Godwin; the King also had the toll of the strand; and "men of Southwark" had the right to "a haw and its toll". Southwark's value to the King was £16.[18] Much of Southwark was originally owned by the church – the greatest reminder of monastic London is Southwark Cathedral, originally the priory of St Mary Overie. During the early Middle Ages, Southwark developed and was one of the four Surrey towns which returned Members of Parliament for the first commons assembly in 1295. An important market occupied the High Street from some time in the 13th century, which was controlled by the city's officers—it was later removed in order to improve traffic to the Bridge, under a separate Trust by Act of Parliament of 1756 as the Borough Market on the present site. The area was renowned for its inns, especially The Tabard, from which Geoffrey Chaucer's pilgrims set off on their journey in The Canterbury Tales.   The continuing defensive importance of London Bridge was demonstrated by its important role in thwarting Jack Cade's Rebellion in 1450;[19] Cade's army tried to force its way across the bridge to enter the City, but was foiled in a battle which cost 200 lives.[20] The bridge was also closed during the Siege of London in 1471, helping to foil attempts by the Bastard of Fauconberg to cross and capture the City. Post-medievalJust west of the Bridge was the Liberty of the Clink manor, which was never controlled by the city, but was held under the Bishopric of Winchester's nominal authority. This lack of oversight helped the area become the entertainment district for London, with a concentration of sometimes disreputable attractions such as bull and bear-baiting, taverns, theatre and brothels.[21] In the 1580s, Reasonable Blackman worked as a silk weaver in Southwark, as one of the first people of African heritage to work as independent business owners in London in that era.[22][23][24] In 1587, Southwark's first playhouse theatre, The Rose, opened. The Rose was set up by Philip Henslowe, and soon became a popular place of entertainment for all classes of Londoners. Both Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare, two of the finest writers of the Elizabethan age, worked at the Rose. In 1599 the Globe Theatre, in which Shakespeare was a shareholder, was erected on the Bankside in the Liberty of the Clink. It burned down in 1613, and was rebuilt in 1614, only to be closed by the Puritans in 1642 and subsequently pulled down not long thereafter. A modern replica, called Shakespeare's Globe, has been built near the original site. The impresario in the later Elizabethan period for these entertainments was Shakespeare's colleague Edward Alleyn, who left many local charitable endowments, most notably Dulwich College. During the Second English Civil War, a force of Kentish Royalist Rebels approached London, hoping the lightly defended city might fall to them, or that the citizens would rise in their favour, however their hopes were quashed when Philip Skippon, in charge of the defence swiftly fortified the bridge making it all but impregnable to the modest Royalist force. On 26 May 1676, ten years after the Great Fire of London, a great fire broke out, which continued for 17 hours before houses were blown up to create fire breaks. King Charles II and his brother, James, Duke of York, oversaw the effort. There was also a famous fair in Southwark which took place near the Church of St George the Martyr. William Hogarth depicted this fair in his engraving of Southwark Fair (1733). Southwark was also the location of several prisons, including those of the Crown or Prerogative Courts, the Marshalsea and King's Bench prisons, those of the local manors' courts, e.g., Borough Compter, The Clink and the Surrey county gaol originally housed at the White Lion Inn (also informally called the Borough Gaol) and eventually at Horsemonger Lane Gaol. One other local family is of note, the Harvards. John Harvard went to the local parish free school of St Saviour's and on to Cambridge University. He migrated to the Massachusetts Colony and left his library and the residue of his will to the new college there, named after him as its first benefactor. Harvard University maintains a link, having paid for a memorial chapel within Southwark Cathedral (his family's parish church), and where its UK-based alumni hold services. John Harvard's mother's house is in Stratford-upon-Avon. UrbanisationIn 1836 the first railway in the London area was created, the London and Greenwich Railway, originally terminating at Spa Road and later extended west to London Bridge.  In 1861, another great fire in Southwark destroyed a large number of buildings between Tooley Street and the Thames, including those around Hays Wharf (later replaced by Hays Galleria) and blocks to the west almost as far as St Olave's Church. The first deep-level underground tube line in London was the City and South London Railway, now the Bank branch of the Northern line, opened in 1890, running from King William Street south through Borough to Stockwell. Southwark, since 1999, is also now served by Southwark, Bermondsey and London Bridge stations on the Jubilee line. Administrative history   Southwark is thought to have become a burh in 886. The area appears in the Domesday Book of 1086 within the hundred of Brixton as held by several Surrey manors.[18] The ancient borough of Southwark, enfranchised in 1295, initially consisted of the pre-existing Surrey parishes of St George the Martyr, St Olave, St Margaret and St Mary.[25] St Margaret and St Mary were abolished in 1541 and their former area combined to create Southwark St Saviour. Around 1555 Southwark St Thomas was split off from St Olave, and in 1733 Southwark St John Horsleydown was also split off.[25] In 1855 the parishes came into the area of responsibility of the Metropolitan Board of Works. The large St George the Martyr parish was governed by its own administrative vestry, but the smaller St John Horsleydown, St Olave and St Thomas parishes were grouped together to form the St Olave District. St Saviour was combined with Southwark Christchurch (the former liberty of Paris Garden) to form the St Saviour's District. In 1889 the area became part of the new County of London.[25] St Olave and St Thomas were combined as a single parish in 1896. The ancient borough of Southwark, was traditionally known simply as The Borough – or Borough – to distinguish it from 'The City', and this name has persisted as an alternative name for the area. The medieval heart of Southwark was also, simultaneously, referred to as the ward of Bridge Without when administered by the city (from 1550 to 1900) and as an aldermanry until 1978.[2] The local government arrangements were reorganised in 1900 with the creation of the Metropolitan Borough of Southwark. It comprised the parishes of Southwark Christchurch, Southwark St Saviours, Southwark St George the Martyr and Newington. The Metropolitan Borough of Southwark was based at the former Newington Vestry Hall, now known as Walworth Town Hall.[26] The eastern parishes that had formed the St Olave District instead became part of the Metropolitan Borough of Bermondsey. In 1965 the two boroughs were combined with the Metropolitan Borough of Camberwell to form the current London Borough of Southwark.[25] A new Diocese of Southwark was established in 1905 from parts of the Diocese of Rochester; the diocese serves large parts of south London and Surrey.[27] Relationship with the City of LondonSouthwark was outside of the control of the City of London and was a haven for criminals and free traders, who would sell goods and conduct trades outside the regulation of the city's Livery Companies. In 1327 the City obtained control from King Edward III of the manor next to the south side of London Bridge known as the Town of Southwark (called latterly the Guildable Manor—i.e., the place of taxes and tolls). The Livery Companies also ensured that they had jurisdiction over the area. From the Norman period manorial organisation obtained through major lay and ecclesiastic magnates. Southwark still has vestiges of this because of the connection with the City of London. In 1327 the city acquired from Edward III the original vill of Southwark and this was also described as "the borough". In 1536 Henry VIII acquired the Bermondsey Priory properties and in 1538 that of the Archbishop. In 1550 these were sold to the city. After many decades of petitioning, in 1550 Southwark was incorporated into the City of London as the ward of Bridge Without. However, the Alderman was appointed by the Court of Aldermen and no Common Councilmen were ever elected. This ward was constituted of the original Guildable Manor and the properties previously held by the church, under a charter of Edward VI, latterly called the King's Manor or Great Liberty. These manors are still constituted by the City under a Bailiff and Steward with their Courts Leet and View of Frankpledge Juries and Officers which still meet—their annual assembly being held in November under the present High Steward (the Recorder of London). The Ward and Aldermanry were effectively abolished in 1978, by merging it with the Ward of Bridge Within. These manorial courts were preserved under the Administration of Justice Act 1977. Therefore, between 1750 and 1978 Southwark had two persons (the Alderman and the Recorder) who were members of the city's Court of Aldermen and Common Council who were elected neither by the City freemen or by the Southwark electorate but appointed by the Court of Aldermen. Contemporary governance and representationThe Borough and Bankside Community Council corresponds to the Southwark electoral wards of Cathedrals and Chaucer.[28] They are part of the Bermondsey and Old Southwark Parliament constituency whose Member of Parliament is Neil Coyle. It is within the Lambeth and Southwark London Assembly constituency. Until 2022 Southwark was the location of City Hall, the administrative headquarters of the Greater London Authority and the meeting place of the London Assembly and Mayor of London. Since 2009, Southwark London Borough Council has its main offices at 160 Tooley Street, having moved administrative staff from the Camberwell Town Hall.[29] Geography and attractions In common with much of the south bank of the Thames, the Borough has seen extensive regeneration in the last decade. Declining wharfage trade, light industry and factories have given way to residential development, shops, restaurants, galleries, bars and most notably major office developments housing international headquarters of accountancy, legal and other professional services consultancies, most notably along London Bridge City and More London between Tooley Street and the riverside. The area is in easy walking distance of the City and the West End. As such it has become a major business centre with many national and international corporations, professional practices and publishers locating to the area. London's tallest skyscraper, the Shard, is next to London Bridge Station. To the north is the River Thames, London Bridge station and Southwark Cathedral. Borough Market is a well-developed visitor attraction and has grown in size. The adjacent units have been converted and form a gastronomic focus for London. Borough High Street runs roughly north to south from London Bridge towards Elephant and Castle. The Borough runs further to the south than realised; both St George's Cathedral and the Imperial War Museum are within the ancient boundaries, which border nearby Lambeth. Its entertainment district, in its heyday at the time of Shakespeare's Globe Theatre (which stood 1599–1642) has revived in the form of the post-1997 reinvention of the original theatre, Shakespeare's Globe, incorporating other smaller theatre spaces, an exhibition about Shakespeare's life and work and which neighbours Vinopolis and the London Dungeon. The Southbank area, primarily in Lambeth but shared with Southwark also hosts many artistic venues. At its heart is the area known as Borough, which has an eclectic covered and semi-covered market and numerous food and drink venues as well as the skyscraper The Shard. The Borough is generally an area of mixed development, with council estates, major office developments, social housing and high value residential gated communities side by side with each other. Another landmark is Southwark Cathedral, a priory then parish church, created a cathedral in 1905, noted for its Merbecke Choir. The area at an advanced stage of regeneration and has the City Hall offices of the Greater London Authority. TransportThe area has three main tube stations: Borough, Southwark and one close to the river, which is combined with a railway terminus; London Bridge. Notable people

See alsoNotes

References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Southwark, London.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||