|

The Social Construction of Reality

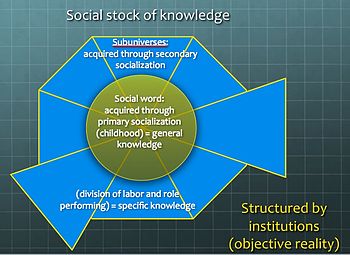

The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge (1966), by Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, proposes that social groups and individual persons who interact with each other, within a system of social classes, over time create concepts (mental representations) of the actions of each other, and that people become habituated to those concepts, and thus assume reciprocal social roles. When those social roles are available for other members of society to assume and portray, their reciprocal, social interactions are said to be institutionalized behaviours. In that process of the social construction of reality, the meaning of the social role is embedded to society as cultural knowledge. As a work about the sociology of knowledge, influenced by the work of Alfred Schütz, The Social Construction of Reality introduced the term social construction and influenced the establishment of the field of social constructionism.[1] In 1998, the International Sociological Association listed The Social Construction of Reality as the fifth most-important book of 20th-century sociology.[2] ConceptsSocial stock of knowledgeEarlier theories (those of, for example, Max Scheler, Karl Mannheim, Werner Stark, Karl Marx, and Max Weber) often focused predominantly on scientific and theoretical knowledge, representing a limited sphere of social knowledge. Customs, common interpretations, institutions, shared routines, habitualizations, the who-is-who and who-does-what in social processes and the division of labor, constitute a much larger part of knowledge in society.

Semantic fieldsThe general body of knowledge is socially distributed, and classified in semantic fields. The dynamic distribution and inter dependencies of these knowledge sectors provide structure to the social stock of knowledge:

Language and signsLanguage also plays an important role in the analysis of integration of everyday reality. Language links up commonsense knowledge with finite provinces of meaning, thus enabling people, for example, to interpret dreams through understandings relevant in the daytime. "Language is capable of transcending the reality of everyday life altogether. It can refer to experiences pertaining to finite provinces of meaning, it can span discrete spheres of reality...Language soars into regions that are not only de facto but also a priori unavailable to everyday experience."p. 40. Regarding the function of language and signs, Berger and Luckmann are indebted to George Herbert Mead and other figures in the field known as symbolic interactionism, as acknowledged in their Introduction, especially regarding the possibility of constructing objectivity. Signs and language provide interoperability for the construction of everyday reality:

Social everyday realitySocial everyday reality is characterized by Intersubjectivity (which refers to the coexistence of multiple realities in this context) (p. 23-25):

This is in contrast to other realities, such as dreams, theoretical constructs, religious or mystic beliefs, artistic and imaginary worlds, etc. While individuals may visit other realities (such as watching a film), they are always brought back to everyday reality (once the film ends) (p. 25). Individuals have the capacity to reflect on these realities, including their own social everyday reality. This type of reflection is often referred to as reflexivity. But, crucially, even reflexivity must draw on some "source material" or be rooted in intersubjectivity. It has, thus, been suggested that: "As agents exercise their reflexive capacities, they bring with them a past consisting of social experiences accumulated or sedimented into stocks of knowledge that provide the requisite guidance for going about their lives and interpreting their social reality".[3] Society as objective realityInstitutionalizationInstitutionalization of social processes grows out of the habitualization and customs, gained through mutual observation with subsequent mutual agreement on the “way of doing things”. This reduces uncertainty and danger and allows our limited attention span to focus on more things at the same time, while institutionalized routines can be expected to continue “as previously agreed”:

Social objective worldsSocial (or institutional) objective worlds are one consequence of institutionalization, and are created when institutions are passed on to a new generation. This creates a reality that is vulnerable to the ideas of a minority which will then form the basis of social expectations in the future. The underlying reasoning is fully transparent to the creators of an institution, as they can reconstruct the circumstances under which they made agreements; while the second generation inherits it as something “given”, “unalterable” and “self-evident” and they might not understand the underlying logic.

Division of laborDivision of labor is another consequence of institutionalization. Institutions assign “roles” to be performed by various actors, through typification of performances, such as “father-role”, “teacher-role”, “hunter”, “cook”, etc. As specialization increases in number as well as in size and sophistication, a civilization's culture contains more and more sections of knowledge specific to given roles or tasks, sections which become more and more esoteric to non-specialists. These areas of knowledge do not belong anymore to the common social world and culture.

Symbolic universesSymbolic universes are created to provide legitimation to the created institutional structure. Symbolic universes are a set of beliefs “everybody knows” that aim at making the institutionalized structure plausible and acceptable for the individual—who might otherwise not understand or agree with the underlying logic of the institution. As an ideological system, the symbolic universe “puts everything in its right place”. It provides explanations for why we do things the way we do. Proverbs, moral maxims, wise sayings, mythology, religions and other theological thought, metaphysical traditions and other value systems are part of the symbolic universe. They are all (more or less sophisticated) ways to legitimize established institutions.

Universe-maintenanceUniverse-maintenance refers to specific procedures undertaken, often by an elite group, when the symbolic universe does not fulfill its purpose anymore, which is to legitimize the institutional structure in place. This happens, for example, in generational shifts, or when deviants create an internal movement against established institutions (e.g. against revolutions), or when a society is confronted with another society with a greatly different history and institutional structures. In primitive societies this happened through mythological systems, later on through theological thought. Today, an extremely complex set of science has secularized universe-maintenance.

Society as subjective realitySocializationSocialization is a two-step induction of the individual to participate in the social institutional structure, meaning in its objective reality.

Primary Socialization takes place as a child. It is highly charged emotionally and is not questioned. Secondary Socialization includes the acquisition of role-specific knowledge, thus taking one's place in the social division of labor. It is learned through training and specific rituals, and is not emotionally charged: “it is necessary to love one's mother, but not one's teacher”. Training for secondary socialization can be very complex and depends on the complexity of division of labor in a society. Primary socialization is much less flexible than secondary socialization. E.g. shame for nudity comes from primary socialization, adequate dress code depends on secondary: A relatively minor shift in the subjective definition of reality would suffice for an individual to take for granted that one may go to the office without a tie. A much more drastic shift would be necessary to have him go, as a matter of course, without any clothes at all.

ConversationConversation or verbal communication aims at reality-maintenance of the subjective reality. What seems to be a useless and unnecessary communication of redundant banalities is actually a constant mutual reconfirmation of each other's internal thoughts, in that it maintains subjective reality.

IdentityIdentity of an individual is subject to a struggle of affiliation to sometimes conflicting realities. For example, the reality from primary socialization (mother tells child not to steal) can be in contrast with second socialization (gang members teach teenager that stealing is cool). Our final social location in the institutional structure of society will ultimately also influence our body and organism.

ReceptionIn 1998 the International Sociological Association listed it as the fifth-most important sociological book of the 20th century, behind Max Weber's The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905) but ahead of Pierre Bourdieu's Distinction (1979).[2][4] InfluenceThe Social Construction of Reality (SCR) is referenced by a very broad range of fields including law, social medicine, philosophy, political science, economics, management and gender studies.[1]: 7 The book was influential in the creation of the field of social constructionism which has developed many subfields, though the concept of constructionism had entered sociology prior to the publication of SCR.[1]: 11 Piaget used the term in his 1950 book, La construction du réel chez l’enfant.[1]: 12 Scholars of social constructionism drew parallels between social constructionism and various post-structuralism and postmodern fields making these theories synonymous with the ideas presented in SCR, though these books did not reference SCR directly.[1]: 13 However, the term social constructionism is used quite broadly; some uses are unrelated to the theory laid out in SCR, and the further a field is from sociology the less likely it is to cite SCR when discussing constructionism.[1]: 9 See alsoNotes

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||