|

Theodora (wife of Justinian I)

Theodora (/ˌθiːəˈdɔːrə/; Greek: Θεοδώρα; c. 490/500 – 28 June 548)[1] was a Byzantine empress and wife of emperor Justinian I. She was from humble origins and became empress when her husband became emperor in 527. She was one of his chief advisers. Theodora is recognized as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Oriental Orthodox Church, and commemorated on 14 November.[2] Early yearsTheodora was of Greek descent,[3] but much of her early life, including the date and place of her birth, is uncertain: for instance, according to Michael the Syrian, her birthplace was in Mabbug, Syria;[4] Nicephorus Callistus Xanthopoulos says Theodora is a native of Cyprus;[5] and the Patria, attributed to George Codinus, claims Theodora came from Paphlagonia.[6] 21st-century historian Clive Foss has also suggested the Egyptian city of Alexandria as a potential place of her birth.[7] The modern consensus seems to be that Theodora most likely was born around 495 and raised in Constantinople.[8] Procopius's Secret History is the foremost source of her life before marriage, but modern scholars regard it as often unreliable and slanderous. Potter, for instance, writes that Procopius' description of Theodora's erotic life "probably was composed as an exaggerated diatribe" and was "certainly not among the most accurate things he ever wrote."[9] Her father, Acacius, was a bear trainer for the Hippodrome's Green faction in Constantinople.[10] Given her father's profession, modern scholars thus argue that it is highly probable Theodora was a native of the capital[11] – this is furthered in Procopius' narrative. Her mother, whose name was not recorded, was a dancer and an actress.[12] She had two sisters, an elder named Comito and a younger named Anastasia.[13] After her father's death, her mother remarried, but the family lacked a source of income because Acacius' position was given away by Asterius, a Green faction official who accepted a bribe in exchange. When Theodora was four, her mother brought her children wearing garlands into the Hippodrome, presenting them as suppliants to the Green faction, but they rebuffed her efforts. Consequently, Theodora's mother approached the Blue faction which took pity on the family and gave the position of bear keeper to Theodora's stepfather.[14] According to Procopius' Secret History, written around 550 AD,[15] Theodora began her work as a prostitute before the onset of adolescence by joining alongside her older sister Comito when she performed onstage[16] and worked in a Constantinople brothel, serving low and high-status customers. Later, she performed on stage.[17] Procopius wrote that Theodora made a name for herself with her pornographic portrayal of Leda and the Swan, where she would have birds eat seeds from her nude body.[18][19] Employment as an actress at the time would have included performing "indecent exhibitions" on stage and providing sexual services off stage. During this time, she may have met Antonina, the future wife of Belisarius who also became a part of the women's court led by Theodora.

Some contemporary authors such as John of Ephesus, also describe Theodora as having come "from the brothel", but this translation of pornae, which most commonly means "prostitutes" is used by John Ephesus to refer to actresses, suggesting that porneion which commonly means "brothel" in classical Greek was used to describe her past as an actress and not the place she came from.[21] Therefore, the association of Theodora with a brothel may only reflect her time on stage as an actress, instead of her being a prostitute.[22] Consistent with the Christian principles of repentance and forgiveness, John wrote of her redemption as a positive tale.[23] Never the less, the modern consensus about Theodora's sexual activity is that, as Potter states, underlying Procopius' inventions "there lies the semblance of fact."[24] Later, Theodora traveled to North Africa as the concubine of a Syrian official named Hecebolus, who became the governor of the Libyan Pentapolis.[25] Procopius alleges that Hecebolus mistreated Theodora, with their relationship dissolving after a quarrel in Africa. Theodora, "destitute of the means of life," settled in Alexandria, Egypt.[18] Some historians speculate that she met Patriarch Timothy III, a Miaphysite, and converted to Miaphysite Christianity there, but there is no reliable evidence that this happened.[26] From Alexandria, she traveled to Antioch, where she met a Blue faction dancer called Macedonia who may have served as an informer for Justinian; according to Procopius, Macedonia often wrote letters to Justinian regarding some high-ranking men in the East whose properties would be subsequently confiscated by Justinian. Afterwards, Theodora returned to Constantinople where she met Justinian. Justinian wanted to marry Theodora but Roman law from Constantine's time barred anyone of senatorial rank from marrying an actress. Equally, giving up this profession did not impact the legality of the marriage as anyone who had been an actress would furthermore be regarded as such. The empress Euphemia, consort of the emperor Justin, also strongly opposed the marriage. Following Euphemia's death in 524, Justin passed a new law allowing reformed actresses to marry outside of their rank if the marriage was approved by the emperor.[27] Shortly thereafter, Justinian married Theodora.[25] According to Procopius, these laws were created specifically for Justinian and Theodora.[22] Theodora had an illegitimate daughter whose name and father are unknown. It also appears that she was married and had children with another Monophysite.[22] The same law that allowed Justinian and Theodora to marry also excused children of former actresses,[28] thus allowing Theodora's daughter to marry a relative of the late emperor Anastasius. This added clause strengthens Procopius's statement that these laws were specifically created for Theodora. Procopius's Secret History claimed that Theodora also had an illegitimate son, John, who arrived in Constantinople several years after Justinian and Theodora's marriage.[29] According to Procopius, when Theodora learned of John's arrival and claims of kinship to her, she secretly had him sent away and he was never heard from again. Some historians, including classics scholar James Allan Evans, believe that Procopius's account of John is unlikely to be factual because Theodora publicly acknowledged her illegitimate daughter and, therefore, would have acknowledged an illegitimate son had one existed.[30] Empress When Justinian succeeded to the throne in 527, Theodora was crowned augusta and became empress of the Eastern Roman Empire. According to Procopius' Secret History, she helped her husband make decisions, plans, and political strategies; participated in state councils; and had great influence over him. Justinian called her his "partner in my deliberations" in Novel 8.1 (AD 535), anti-corruption legislation where provincial officials had to take an oath to the emperor and Theodora.[31] Sources generally agree on her character being vindictive but loyal and determined. She secured her influence though instilling fear in her subjects with little care for the consequences.[22] The Nika riots Two major party factions were at odds before, during, and after Justinian and Theodora's reign – the Blues and the Greens. Street violence between the parties was a regular event. When Justinian became emperor, he was determined to make the city a more lawful and orderly community. However, his efforts were not perceived as being even-handed since both his and Theodora's favor were believed to align with the Blues; Justinian was thought to prefer the Blues, while Theodora's family was abandoned by the Greens after her father's death and given support by the Blues as a child. Consequently, the Greens felt isolated and frustrated.[33] During a riot between the two factions in early January 532, the urban prefect Eudaemon arrested a group of both Green and Blue felons and convicted them of murder. They were sentenced to death but two of the felons, one Blue and one Green, survived the hanging when the scaffold collapsed. Three days later, at the Hippodrome where the public was permitted to entreat the emperor on issues, the two factions shouted for mercy to be shown to the imprisoned men. When the emperor continued to be unresponsive to their demands, the angry factions united chanting "Nika", meaning "conquer". Justinian recognized the danger of these factions uniting against Theodora and himself and retreated to the palace.[34] The rioters set many public buildings on fire and proclaimed a new emperor, Hypatius, the nephew of the former emperor Anastasius I. Unable to control the mob, Justinian and his officials prepared to flee. According to Procopius, Theodora was the one who persuaded Justinian and his court from fleeing and take the offensive instead.[22] Procopius wrote that Theodora spoke against leaving the palace at a meeting of the government council, underlining the significance of someone who dies as a ruler instead of living as an exile or in hiding.[35] According to Procopius, Theodora interrupted the emperor and his counselors, saying:

Her speech motivated the men, including Justinian. He ordered his loyal troops to attack the demonstrators in the Hippodrome, resulting in the deaths of over 30,000 civilian rebels. Other reports claim greater numbers of victims, with the numbers increasing with the distance from Constantinople; the scholar and historian Zachariah of Mytilene estimated the dead at more than 80,000.[37] Despite his claims that he was unwillingly named emperor by the mob, Hypatius was put to death by Justinian. In one source, this came at Theodora's insistence.[38] Some scholars interpret Procopius' account intended to portray Justinian as more cowardly than his wife, noting that Procopius probably fabricated her speech. Changing the term "tyranny" to "royal purple", possibly reflects Procopius' desire to link Theodora and Justinian to ancient tyrants.[39] Following the Nika revolt, Justinian soon felt secure enough to reinstate John the Cappadocian and quaestor Tribonian, the two ministers that were dismissed to appease the factions. In retaliation for their disloyalty, the nineteen senators who participated in the attempted Nika coup had their estates destroyed.[citation needed] Hypatius and Pompeius' bodies were dumped in the sea. Later life Justinian and Theodora constructed a number of new buildings in Constantinople, including aqueducts, bridges, and more than 25 churches,[citation needed] the most famous of which is Hagia Sophia. Theodora was said to have been interested in the court ceremony. According to Procopius, all senators, including patricians were required to prostrate themselves whenever entering the Imperial couple's presence.

The couple also made it clear that their relationship with the civil militia was that of master to slave. They also supervised the magistrates to reduce bureaucratic corruption.[citation needed] Theodora considered the praetorian prefect John the Cappadocian as her enemy because of his independence and great influence and because he was slandering her to the emperor. Theodora and Antonina devised a plot to bring down John. She was also hostile to Germanus, the cousin of Justinian. On the other hand, the praetorian prefect Peter Barsymes was Theodora's close ally. She engaged in matchmaking, forming a network of alliances between new and old powers, including Emperor Anastasius' family, pre-existing nobility, and the new monarchy of Justinian's family. According to Secret History, she attempted to marry her grandson Anastasius to Joannina, Belisarius' and Antonina's daughter and heiress, against her parents' will. Although the marriage was initially rejected, the couple eventually married. The marriages of her sister Comito to general Sittas and her niece Sophia to Justinian's nephew Justin II, who would succeed to the throne, are suspected to have been engineered by Theodora. She also gave reception and sent letters and gifts to Persian and foreign ambassadors and the sister of Kavad.[40] Theodora was involved in helping underprivileged women. In a well-known instance, she compelled General Artabanes, who intended to wed Justinian's niece, to reclaim the wife he abandoned.[6] She sometimes would "buying girls who had been sold into prostitution, freeing them, and providing for their future."[41] She created a convent on the Asian side of the Dardanelles called the Metanoia (Repentance), where the ex-prostitutes could support themselves.[25] Procopius' Secret History maintained that instead of preventing forced prostitution (as in Buildings 1.9.3ff), Theodora is said to have "rounded up" 500 prostitutes, confining them to a convent. They sought to escape "the unwelcome transformation" by leaping over the walls (SH 17). This can be seen as an attempt to escape or take their own lives. This can be interpreted as a way for Procopious to diminish the good deeds of Theodora.[42] On the other hand, chronicler John Malalas wrote positively about the convent, declaring that Theodora "freed the girls from the yoke of their wretched slavery."[43] As well as helping ex prostitutes, Theodora tried to eradicate prostitution all together. In 528, Theodora and Justinian ordered the closure of the brothels and the arrest of their keepers and procurers. She paid their owners back the purchase fee, freeing the prostitutes from their captivity. To facilitate the start of their new lives, she supplied the liberated women with clothing and gifted each of them a gold nomisma.[6] The biased perspectives of Procopius towards Theodora display his failure to understand the policy changes Theodora and Justinian advocated possibly reflected remorse she had regarding her past choices and aimed to shield young women from repeating her own errors.[44] Justinian's legislations also expanded the rights of women in divorce and property ownership, instituted the death penalty for rape,[45] forbade exposure of unwanted infants, gave mothers some guardianship rights over their children, and forbade the killing of a wife who committed adultery. In Wars, Procopius mentioned that Theodora was naturally inclined to assist women in misfortune and, according to Secret History, she was accused of unfairly championing the wives' causes more so when they were charged with adultery (SH 17). The code of Justinian only allowed women to seek a divorce from their husbands due to either abuse or a wife catching their husband in obvious adultery. Regardless, women seeking a divorce had to provide clear evidence of their claims.[46] Procopius describes Theodora as causing women to "become morally depraved" due to her and Justinian's legal actions.[47] Religious policy

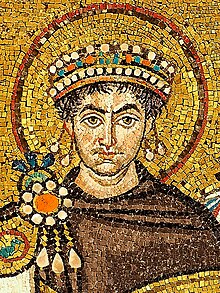

Since Justinian was not the recognized head of any of the sects of the Christian church, his focus was on reducing or eliminating the friction between the various Christian sects and the Empire. As a Christian emperor, he believed he should be in harmony with the head(s) of the Church. Because Justinian was a Chalcedonian and Theodora was a Miaphysite (Non-Chalcedonian), Justinian worked to heal the divide between the Constantinopolitan church and the Roman church. He wanted a united Church that would “partner” with one Emperor (himself); the Emperor would manage human affairs and the priesthood would manage the divine affairs of God. Since the Emperor was accountable to the law, Justinian ensured that the law recognized the Emperor as the law incarnate – with universal authority of divine origin. Consequently, he used the law to micromanage the implementation of religion through laws aimed at its very execution.[48] Theodora worked against her husband's support of Chalcedonian Christianity in the ongoing struggle for the dominance of each faction.[49] As a result, she was accused of fostering heresy and undermining the unity of Christendom. However, Procopius and Evagrius Scholasticus suggested that Justinian and Theodora were merely pretending to oppose each other. John of Ephesus, a key figure within the Monophysite movement, wrote of the significant contributions of Theodora in assisting church building projects and supporting the poor.[50] Her involvement also was documented as being instrumental to the protection of the Monophysites from the Chalcedonians.[51] Theodora founded a Miaphysite monastery in Sykae and provided shelter in the palace for Miaphysite leaders who faced opposition from the majority of Chalcedonian Christians, like Severus and Anthimus. Anthimus had been appointed Patriarch of Constantinople under her influence and, after the ex-communication order, he was hidden in Theodora's quarters until her death in twelve years. When the Chalcedonian Patriarch Ephraim provoked a violent revolt in Antioch, eight Miaphysite bishops were invited to Constantinople; Theodora welcomed them and housed them in the Hormisdas Palace, Justinian and Theodora's dwelling before they became Emperor and Empress. Theodora persistently provided sanctuary for persecuted Miaphysites within the Palace, accommodating such a significant number of monks that, in one incident, several hundred gathered in a grand chamber, causing the floor to collapse.[52] Furthermore, the Empress was instrumental in building the Church of Sergius and Bacchus, located next to Hormisdas palace. The dedicatory inscription, which remains visible to this day, proudly proclaims: ‘May he [Sergius] increase the power of the God-crowned Theodora whose mind is adorned with piety, whose constant toil lies in unsparing efforts to nourish the destitute.’ [53] When Pope Timothy III of Alexandria died, Theodora enlisted the help of the Augustal Prefect and the Duke of Egypt to make Theodosius, a disciple of Severus, the new pope. Thus, she outmaneuvered her husband who wanted a Chalcedonian successor. However, Pope Theodosius I of Alexandria and the imperial troops could not hold Alexandria against Justinian's Chalcedonian followers; Justinian exiled the pope and 300 Miaphysites to the fortress of Delcus in Thrace. When Pope Silverius refused Theodora's demand that he remove the anathema of Pope Agapetus I from Patriarch Anthimus, she sent Belisarius instructions to find a pretext to remove Silverius. When this was accomplished, Pope Vigilius was appointed in his stead. In Nobatae, south of Egypt, the inhabitants were converted to Miaphysite Christianity about 540. Justinian was determined that they should be converted to the Chalcedonian faith, with Theodora equally determined that they should become Miaphysites. Justinian made arrangements for Chalcedonian missionaries from Thebaid to go with presents to Silko, the King of the Nobatae. in response, Theodora prepared her missionaries and wrote to the Duke of Thebaid, asking that he should delay her husband's embassy so that the Miaphysite missionaries would arrive first. The duke was canny enough to thwart the easygoing Justinian instead of the unforgiving Theodora. He made sure that the Chalcedonian missionaries were delayed; when they eventually reached Silko, they were sent away. The Nobatae had already adopted the Miaphysite creed of Theodosius. DeathTheodora's death is recorded by Victor of Tonnena, with the cause uncertain; however, the Greek terms used are often translated as "cancer".[54] Victor notes the death date was 28 June 548 and her age as 48, although other sources report that she died at 51,[55][56] or "about 53."[57] Later accounts attribute the death to breast cancer but this was not identified in the original report, where the use of the term "cancer" probably referred to a more general "suppurating ulcer or malignant tumor".[56] She was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. During a procession in 559, 11 years after her death, Justinian visited her tomb and lit candles in her memory.[58] HistoriographyThe main historical sources about her life are the works of her contemporary Procopius. Procopius was a member of the staff of Belisarius, a field marshal for Justinian, who is perhaps the best-known officer of Justinian's officers because of Procopius's writings.[59] Procopius wrote three portrayals of the Empress. The Wars of Justinian, or "History of the Wars," was largely completed by 550,[60] and paints a picture of a courageous woman who helped save Justinian's attempt at the throne. Procopius probably wrote the Secret History around the same time.[61] The work has sometimes been interpreted as representing disillusionment with Emperor Justinian, the empress, and his patron, Belisarius. Justinian is depicted as cruel, corrupt, extravagant, and incompetent; while Theodora is shrewish and openly sexual. Procopius' Buildings of Justinian, written around 554, after Secret History,[62] is a panegyric that paints Justinian and Theodora as a pious couple. It presents particularly flattering portrayals of them; her piety and beauty are praised. It is important to note that Theodora was dead when the work was published, and, Justinian most likely commissioned the work.[63] Her contemporary John of Ephesus writes about Theodora in Lives of the Eastern Saints and mentions an illegitimate daughter.[64] Theophanes the Confessor mentions some familial relations of Theodora that were not mentioned by Procopius. Victor Tonnennensis notes her familial relation to the next empress, Sophia. Bar-Hebraeus and Michael the Syrian both say Theodora was from the city of Daman, near Kallinikos, Syria. These later Miaphysite sources account say that Theodora is the daughter of a priest, trained in the pious practices of Miaphysitism since birth. The Miaphysites tend to regard Theodora as one of their own. Their account is also an alternative to that of contemporary John of Ephesus.[65] Many modern scholars prefer Procopius' account.[64] Critiques of ProcopiusSome modern historians argue that Procopius is not necessarily a reliable source for understanding Theodora, but he provides a glimpse into the changing values and norms of the period.[30] Some stories reflect the values of some educated people that a good empress is pious and chaste while a bad empress is sexually promiscuous and greedy.[66] The portrayal of Justinian and Theodora as demons in the Secret History may reflect a common contemporary belief. For Procopius, the imperial couple's actions that cannot be rationally explained were the result of evil demons.[67] However, other modern historians believe that Procopius' narrative about Theodora is more reliable than often thought.[22] Her background in theatre, the legislation change that allowed her to marry to Justinian and her ruthlessness against her enemies are corroborated by other 6th century sources.[68] Texts other than Procopius' Secret History confirm that she was involved in the downfall of Pope Silverius and the imperial secretary and comes excubitorum Priscus. Therefore, Procopius may have embellished, rather than invented, the story.[22] Lasting influenceAccording to one historian, "No empress left so profound a mark on the imagination of her people as did Theodora.[69] The Miaphysites believed Theodora's influence on Justinian was so strong that, after her death, he worked to bring harmony between the Miaphysites (Non-Chalcedonian) and the Chalcedonian Christians and kept his promise to protect her little community of Miaphysite refugees in the Hormisdas Palace. Theodora provided much political support for the ministry of Jacob Baradaeus. Olbia in Cyrenaica was renamed Theodorias after Theodora. (It was common for ancient cities to rename themselves to honor an Emperor or Empress.) Now called Qasr Libya, the city is known for its sixth-century mosaics. The settlement of Cululis (modern-day Ain Jelloula) in what is now Tunisia (Africa Proconsularis) was also renamed Theodoriana after Theodora.[4] Theodora and Justinian are represented in mosaics in the Basilica of San Vitale of Ravenna, Italy, which were completed a year before her death after 547 when the Byzantines retook the city. She is depicted in full imperial garb, endowed with jewels befitting her role as empress. Her cloak is embroidered with imagery of the three kings bearing their gifts for the Christ child, symbolizing a connection between her and Justinian bringing gifts to the church. In this case, she is shown bearing a communion chalice. In addition to the religious tone of these mosaics, other mosaics depict Theodora and Justinian receiving the vanquished kings of the Goths and Vandals as prisoners of war, surrounded by the cheering Roman Senate. The Emperor and Empress are recognized for both victory and in generosity in these large-scale public works.[70] In more recent times, plays, operas, films, and novels have been written about Theodora.[71] Media portrayal Art

Books

Film

Theater

Video games

Music

NotesCitations

General and cited references

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Empress Theodora (6th century). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||