|

Two-party-preferred vote

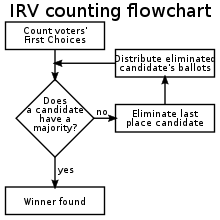

In Australian politics, the two-party-preferred vote (TPP or 2PP), commonly referred to as simply preferences, is the result of an election or opinion poll after preferences have been distributed to the two candidates with the highest number of votes who, in some cases, can be independents. For the purposes of TPP, the Liberal/National Coalition is usually considered a single party, with Labor being the other major party. Typically the TPP is expressed as the percentages of votes attracted by each of the two major parties, e.g. "Coalition 50%, Labor 50%", where the values include both primary votes and preferences. The TPP is an indicator of how much swing has been attained/is required to change the result, taking into consideration preferences, which may have a significant effect on the result. The TPP assumes a two-party system, i.e. that after distribution of votes from less successful candidates, the two remaining candidates will be from the two major parties. However, in some electorates that is not the case. The two-candidate-preferred vote (TCP) is the result after preferences have been distributed, using instant-runoff voting, to the final two candidates, regardless of which party the candidates represent. For electorates where the two candidates are from the major parties, the TCP is also the TPP. For electorates where these two candidates are not both from the major parties, preferences are notionally distributed to the two major parties to determine the TPP. In this case the TPP differs from the TCP, and is not informative. TPP results above seat-level, such as a national or statewide TPP, are also informative only and have no direct effect on the election outcome. The full allocation of preferences under instant-runoff voting is used in the lower houses of the Federal, Queensland, Victorian, Western Australian, South Australian, and Northern Territory parliaments, as well as the upper house of Tasmania. The New South Wales lower house uses optional-preference instant runoff voting – with some votes giving limited or no preferences, TPP/TCP is not as meaningful. TPP/TCP does not occur in the Tasmanian lower house or the Australian Capital Territory due to a different system altogether, the Hare–Clark single transferable vote system. Aside from Tasmania, TPP/TCP is not used in any other upper houses in Australia, with most using the proportional single transferable vote system.[1] HistoryAustralia originally used first-past-the-post voting as used by the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. Federal election full-preference instant-runoff voting was introduced after the 1918 Swan by-election, and has been in use ever since. In that by-election, candidates from the Australian Labor Party, the Nationalist Party government (predecessor to the United Australia Party and Liberal Party of Australia), and the emerging National Party of Australia (then Country Party) all received around a third of the vote, however, as Labor had a plurality of three percent, it won the seat. The new system allowed the two non-Labor parties to compete against one another in many seats without risking losing the seat altogether. It is increasingly uncommon for seats to be contested by more than one Coalition candidate. For example, in the 2010 federal election, only three seats were contested by more than one Coalition candidate. With the popularity of parties such as the Greens and One Nation, preference flows are very significant for all parties in Australia. Not distributing preferences was historically common in seats where a candidate received over 50 percent of the primary vote. Federal seat and national TPP results have only been produced as far back as 1937, though it was not uncommon in the next few decades for major parties at federal elections to not field a candidate in a few "safe" seats, but since 1972, all seats at federal elections have been contested by the major parties. Full preference distributions have occurred in all seats since 1983.[2] Until recently, South Australian state elections had boundaries strategically redrawn before each election with a fairness aim based on the prior election TPP vote, the only state to do so. The culmination of the historical state lower house seat malapportionment known as the Playmander eventually saw it legislated after 1989 that the Electoral Commission of South Australia redraw boundaries after each election with the objective of the party that receives over 50 percent of the TPP vote at each forthcoming election forms government. Nationally in 1983/84, minor gerrymandering by incumbent federal governments was legislated against with the formation of the independent Commonwealth statutory authority, the Australian Electoral Commission.[3] ProcedureUnder the full-preference instant-runoff voting system, in each seat, the candidate with the lowest vote is eliminated and their preferences are distributed; this process repeats until only two candidates remain. Whilst every seat has a TCP result, seats where the major parties have come first and second are commonly referred to as having a TPP result. In a TCP contest between Labor and the NSW/Vic Nationals and without a Liberal candidate, this is also considered a TPP, with the Nationals in these states considered a de facto major party within the Liberal/National Coalition. In seats where the major parties do not come first and second, differing TPP and TCP results are returned. When only one of two major parties contest a seat, such as at some by-elections, only a TCP result is produced. Swings in Australian parliaments are more commonly associated with the TPP vote. At the 2013 federal election, 11 of 150 seats returned differing TPP and TCP figures ("non-classic seats"), indicating a considerable two-party system.[4] The tallying of seat TPP results gives a statewide and/or national TPP vote. Non-classic seats have votes redistributed for informational purposes to the major parties so that every seat has a TPP result. Whilst the TCP is the determining factor in deciding which candidate wins a seat, the overall election TPP is statistical and indicative only, as swings in seats are not uniform, and a varying range of factors can influence marginal-seat wins with single-member electorates. Several federal elections since 1937 have seen a government elected with a minority of the TPP vote: 1940 (49.7%), 1954 (49.3%), 1961 (49.5%), 1969 (49.8%), 1990 (49.9%) and 1998 (49.0%). As the TPP vote rather than the primary vote is a better indicator of who is in front with seats won and lost on a preferential basis, Australian opinion polls survey voter intention with a TPP always produced. However, these TPP figures tend to be calculated based on preference flows at the previous election rather than asked at the time of polling. The difference between the two is usually within the margin of error (usually +/– 3 percentage points). History has shown that prior-election preference flows are more reliable.[5] Three-candidate preferred voteAs traditional two party preferred electorates began to turn into three party contests, the order of elimination began to become more important in determining the result, which often would not become clear until all but three candidates were excluded. Early examples of this included Maiwar at the 2017 Queensland State Election, in which the Green candidate came third on the primary vote, but earned enough preferences to make it into the top two, and win the seat based on Labor preferences, who were initially second place. This requires a primary vote, wherein the 1st placed candidate wins a significant proportion of the primary vote, but loses as the second and third placed candidates outnumber the first and have strong preference flows to each other, or the top three candidates all approximately poll a similar amount. At the 2022 Federal Election, the AEC performed three candidate counts for the first time in the seats of Macnamara, and Brisbane, which fulfilled the latter and former criteria respectively.[6] AnalysisAfter the count has taken place, it is possible to analyze the ultimate preference flows for votes cast for the parties that were ultimately excluded from the TPP calculation, in order to determine if the composite flow would have significantly affected the final result. Such an exercise is shown for the 2017 by-election in Bennelong:

Preference flows in federal elections

ExamplesFederal, Swan 1918

The result of the 1918 Swan by-election, the first-past-the-post election which caused the government of the day to introduce full-preference instant-runoff voting, under which Labor would have been easily defeated. Labor won the seat, and their majority was 3.0 points (34.4 minus 31.4). No swings are available as the Nationalists retained the seat unopposed at the previous election. Federal, Adelaide 2004

It can be seen that the Liberal candidate had a primary vote lead over the Labor candidate. In a first-past-the-post vote, the Liberals would have retained the seat, and their majority would be said to be 3.4 points (45.3 minus 41.9). However, under full-preference instant-runoff voting, the votes of all the minor candidates were distributed as follows:

The process of allocating the votes can be more succinctly shown thus:

Thus, Labor defeated the Liberals, with 85 percent of Green and Green-preferenced voters preferencing Labor on the last distribution. Labor's TPP/TCP vote was 51.3 percent, a TPP/TCP majority of 1.3 points, and a TPP/TCP swing of 1.9 points compared with the previous election. South Australia, Frome 2009

The 2009 Frome by-election was closely contested, with the result being uncertain for over a week.[11][12][13] Liberal leader Martin Hamilton-Smith claimed victory on behalf of the party.[14][15][16] The result hinged on the performance of Brock against Labor in the competition for second place. Brock polled best in the Port Pirie area, and received enough eliminated candidate preferences to end up ahead of the Labor candidate by 30 votes.

Brock received 80 percent of Labor's fifth count preferences to achieve a TCP vote of 51.72 percent (a majority of 665 votes) against the Liberal candidate.[18][19] The by-election saw a rare TPP swing to an incumbent government, and was the first time an opposition had lost a seat at a by-election in South Australia.[20][21] The result in Frome at the 2010 state election saw Brock come first on primary votes, increasing his primary vote by 14.1 points to a total of 37.7 percent and his TCP vote by 6.5 points to a total of 58.2 percent. Despite a state-wide swing against Labor at the election, Labor again increased its TPP vote in Frome by 1.8 points to a total of 50.1 percent. Federal, Melbourne 2010

In this example, the two remaining candidates/parties, one a minor party, were the same after preference distribution at both this election and the previous election. Therefore, differing TPP and TCP votes, margins, and swings resulted.[22] South Australia, Port Adelaide 2012

At the 2012 Port Adelaide state by-election, only a TCP could be produced, as the Liberal Party of Australia (and Family First Party and independent candidate Max James), who contested the previous election and gained a primary vote of 26.8 percent (and 5.9 percent, and 11.0 percent respectively), did not contest the by-election. On a TPP margin of 12.8 points from the 2010 election, considered a safe margin on the current pendulum, Labor would probably have retained their TPP margin based on unchanged statewide Newspoll since the previous election. Labor retained the seat on a 52.9 percent TCP against Johanson after the distribution of preferences.[23][24][25] Unlike previous examples, neither a TPP or TCP swing can be produced, as the 2010 result was between Labor and Liberal rather than Labor and independent with no Liberal candidate. An increase or decrease in margins in these situations cannot be meaningfully interpreted as swings. As explained by the ABC's Antony Green, when a major party does not contest a by-election, preferences from independents or minor parties that would normally flow to both major parties does not take place, causing asymmetric preference flows. Examples of this are the 2008 Mayo and 2002 Cunningham federal by-elections, with seats returning to TPP form at the next election.[26] This contradicts News Ltd claims of large swings and a potential Liberal Party win in Port Adelaide at the next election.[27][28] House of Representatives primary, two-party and seat results

A two-party system has existed in the Australian House of Representatives since the two non-Labor parties merged in 1909. [citation needed] The 1910 election was the first to elect a majority government, with the Australian Labor Party concurrently winning the first Senate majority. Prior to 1909 a three-party system existed in the chamber. A two-party-preferred vote (2PP) has been calculated[citation needed] since the 1919 change from first-past-the-post to preferential voting and subsequent introduction of the Coalition. ALP = Australian Labor Party, L+NP = grouping of Liberal/National/LNP/CLP Coalition parties (and predecessors), Oth = other parties and independents.

Non-standard contestsIn seats not held or won by minor parties, the two-party-preferred contest is almost always between either both major parties (Coalition vs. Labor) or (less commonly) between a major party and an independent, there have been some cases in certain electorates where the contest has been between a major party and a minor party (and the major party wins). Federal examplesIn many inner-city seats that are safely held by Labor, the Greens finish second place. As of 2022, this occurred in the seats of Cooper and Wills in inner-city Melbourne, Grayndler and Sydney in inner-city Sydney and (since 2022) Canberra, which covers the inner-city and eastern suburbs of Canberra. In 2019, the Greens also finished second for the first time in the Melbourne seat of Kooyong, which was held by the Liberals until 2022, when it was won by teal independent Monique Ryan. In 2016, the Greens also finished second in the seats of Higgins in Melbourne and Warringah in Sydney. The Greens also finished second in the now-abolished Melbourne seat of Batman in the 2010, 2013 and 2016 elections, as well as in the 2018 by-election. Plus, before the Greens won the seat of Melbourne in 2010, the Greens had finished second in that electorate in 2007. In 2016 and 2019, One Nation finished second in the seat of Maranoa in outback Queensland. In 2016, the Nick Xenophon Team (NXT) finished second in three South Australian electorates: Barker, Grey and Port Adelaide (the latter of which has since been abolished). State examplesIn New South Wales, there were only two electorates where minor parties finished second to a major party at the 2023 state election (Labor won both electorates); the Greens finished second in Summer Hill and One Nation finished second in Cessnock.[29] At the previous state election in 2019, the Greens finished second in four seats (Davidson, Manly, Pittwater and Vaucluse), all of which were won by the Liberals and were all located in Sydney.[30] In Victoria, the Greens finished second to Labor in four Melbourne seats in 2022. These were Footscray, Northcote, Pascoe Vale, Preston.[31] In Queensland, One Nation often finishes second in many regional electorates. One Nation holds only one seat in the Queensland Parliament, however, which is the seat of Mirani (which was gained from Labor in 2017). At the 2020 state election, One Nation finished second in just one seat, Bundamba, where they finished second to Labor.[32] This happened again in Bundamba at a by-election held in the same year.[33] At the previous election in 2017, however, One Nation finished second in 18 seats across Queensland. At this election, the Greens finished second in South Brisbane, a seat they gained in 2020.[34] In Western Australia, the Greens finished second to Labor in Fremantle at the 2021 state election.[35] Graphical summaryFederal

Two-party-preferred results of Australian federal elections (since 1949).[36] New South WalesVictoriaQueensland

Two-party-preferred results of Queensland state elections (since 2009).

Two-party-preferred results of Queensland state elections (1983-1992). Western Australia

Two-party-preferred results of Western Australian state elections (since 1974). South Australia

Two-party-preferred results of South Australian state elections (since 1975). Northern Territory

Two-party-preferred results of Northern Territory general elections (since 1983). See alsoReferences

External links |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||