|

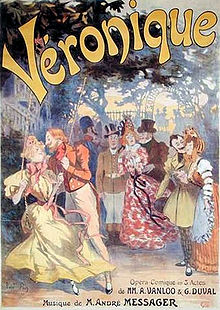

Véronique (operetta) Véronique is an opéra comique in three acts with music by André Messager and words by Georges Duval and Albert Vanloo. The opera, set in 1840 Paris, depicts a dashing but irresponsible aristocrat with complicated romantic affairs, eventually paired with the resourceful heroine. Véronique is Messager’s most enduring operatic work. After its successful premiere in Paris in 1898, it was produced across continental Europe, Britain, the US and Australia. It remains part of the operatic repertoire in France. Background and first productionAfter a fallow period in the mid-1890s, Messager had an international success with Les p'tites Michu (1897). In 1898 his improved fortunes continued when he was appointed musical director of the Opéra-Comique in Paris.[1] His work as a conductor left him little time for composition, and Véronique was his last stage work for seven years, despite its being his most successful work thus far.[2] His librettists were his collaborators from Les p'tites Michu. Before working with Messager, Vanloo had collaborated with Offenbach, Lecocq and Chabrier,[3] and Duval had written a succession of musical and non-musical comic pieces since the mid-1870s.[4] The stars of the Théâtre des Bouffes Parisiens company, Mariette Sully and Jean Périer, were well known and popular figures with Paris audiences, and among the supporting players were singers familiar from Les p'tites Michu, including Maurice Lamy, Victor Regnard and Brunais.[5][6] Véronique was first performed at the Bouffes Parisiens on 10 December 1898.[5] It ran until April 1899, a total of 175 performances.[7] Roles

SynopsisThe action takes place in and around Paris during the reign of Louis Philippe, in 1840. Act 1

The lifestyle of Vicomte Florestan, a dashing but feckless young aristocrat, has left him in severe debt. His uncle, tired of paying off Florestan's debts, has made him promise to get married or go to prison as a bankrupt. Florestan has chosen the arranged marriage; he will be presented to Hélène de Solanges, the rich heiress chosen as his fiancée, that evening at a court ball. Florestan has been having an affair with Agathe Coquenard, the wife of the owner of the florist shop where the action takes place. Old Monsieur Coquenard, who flirts with the flower shop girls, is hoping that, despite his incompetence with a sword, his nomination to be a captain in the Garde Nationale will arrive soon. Just arrived in Paris, Hélène (who has never met Florestan) and her aunt, the Countess Ermerance de Champ d’Azur, now visit the shop to buy their corsages for a ball the countess is giving to celebrate her niece's engagement. Hélène is not pleased to be entering an arranged marriage. Their servant Séraphin is also eagerly anticipating his marriage and wants to slip away to his wedding feast. Florestan arrives at the shop (guarded by Loustot to ensure he does not run off) and flirts with the shop girls. Hélène and Ermerance overhear a conversation where Florestan breaks off his liaison with Agathe, in the process learning that he is Hélène's intended husband. When Florestan complains that he must leave Agathe for a simple girl from the provinces, Hélène vows to take revenge on him, although she finds him handsome. To celebrate the last day of his bachelorhood, Florestan invites the entire staff of Coquenard’s shop for a party in Romainville. Hélène and Ermerance disguise themselves as working girls using the names Véronique and Estelle. Coquenard finally receives his national guard nomination, and in his excitement he hires Véronique and Estelle as shop assistants. "Véronique" succeeds in gaining Florestan's attention, to the annoyance of Madame Coquenard, whose husband also shows interest in the new flower girl. Florestan invites Véronique and Estelle to join the party. Act 2

Séraphin and his bride Denise are celebrating their wedding in a rustic setting. Monsieur Coquenard meanwhile flirts with Hélène's aunt, and Loustot is much taken by Agathe. The vicomte passionately expresses his love for Véronique, who gently mocks him, feigning shyness. Following a donkey ride and courting on a swing, Florestan decides that he is in love with Véronique and that he will not attend the ball that night; he sends away the carriages. Séraphin now recognises "Véronique" and "Estelle", but they tell him to keep quiet. Now, to complete the trick, Hélène and Ermerance borrow their servant's cart to return to Paris, leaving a letter for Florestan from Véronique apologising for her departure and suggesting that they might meet again soon. He swears that he will go to prison rather than risk marriage with his unknown fiancée. Loustot arrests him. Act 3

Ermerance reflects on her wooing by Coquenard, while Hélène looks forward to seeing Florestan again and being introduced to him in her real identity. Captain Coquenard and his wife have mysteriously been invited to the court ball. They meet Estelle and Véronique, and realise who they are. Agathe tells Hélène that, in love with Véronique, Florestan decided on jail rather than marry a stranger. Hélène swiftly pays off his debts to effect his release. When he arrives at the ball, Agathe mocks Florestan and reveals to him that Véronique is Hélène, but his embarrassment makes him reject Hélène. There is soon a reconciliation however, and in general rejoicing the marriage is sealed. Musical numbers

Revivals and adaptationsVéronique was Messager's most successful operetta. It was revived frequently in France during the first part of the 20th century. Revivals played at the Théâtre des Folies-Dramatiques on 30 January 1909, the Théâtre de la Gaîté-Lyrique on 1 March 1920 (with Edmée Favart, Périer and Tarriol-Baugé, and a new waltz written for the production by Messager).[8] The work made its first appearance at the Opéra-Comique on 7 February 1925 in a one-off charity performance featuring Favart, Baugé and Tarriol-Baugé, conducted by Albert Wolff.[9] There was another revival at the Gaîté-Lyrique in 1936;[10] a wartime revival at the Théâtre Mogador, Paris, in April 1943 with Suzanne Baugé, Maurice Vidal and Hélène Lavoisier, was in a grand production that, according to Richard Traubner, "overpowered its fragility".[11]  The work received its first run at the Opéra-Comique in Paris in 1978–79, with Danielle Chlostawa, François le Roux and Michel Roux, conducted by Pierre Dervaux.[12] It was revived there in 1980–81 (with Marie-Christine Pontou and Gino Quilico). More recently it was mounted at the Théâtre du Châtelet in January 2008, directed by Fanny Ardant.[13] The opera was presented in Vienna and Cologne (as Brigitte) in 1900, and then Riga in 1901 and Berlin in 1902.[14] It was produced in Lisbon in 1901 and Geneva in 1902.[14] In London it was given in French at the Coronet Theatre in 1903,[15] and in English at the Apollo Theatre, adapted by Henry Hamilton with lyrics by Lilian Eldée and alterations and additions by Percy Greenbank, produced by George Edwardes. This production opened on 18 May 1904, and ran for 496 performances.[16] The principal players were Rosina Brandram (Ermerance), Sybil Grey (Aunt Benoit), Fred Emney (Loustrot), Kitty Gordon (Mme. Coquenard), George Graves (Coquenard), Lawrence Rea (Florestan) and Ruth Vincent (Hélène).[16][n 1] An Italian version was given in Milan in the same year.[14] A New York production opened at the Broadway Theatre on 30 October 1905, featuring Vincent, Rea, Gordon and John Le Hay. Messager conducted the first night, but The New York Times nonetheless wondered how French the piece remained after two years of continuous anglicisation by its English performers.[18] The production ran until 6 January 1906, a total of 81 performances.[19] The first Australian production was in Sydney in January 1906.[20] The Australian company took the opera to New Zealand, where it opened at the Theatre Royal, Christchurch in June 1906.[21] The following year, the opera was given in Bucharest.[14] Productions followed in Spain and Switzerland.[22] Critical receptionThe Parisian critics were enthusiastic in their praise of the work. L'Eclair called it "A triumphant success, an exquisite score and an excellent interpretation".[23] The reviewer in Le Soleil said that he had drunk in and savoured Messager's music, "believing I was drinking from some fountain of youth. Thanks be to the two librettists and the composer!".[23] In L'Événement Arthur Pougin said that it was a long time since there had been an opérette with "a score so fine, so beautifully worked in its elegant clarity".[23] Le National commented, "It is exquisite, this music – exquisite grace, finesse and distinction, in the discreet tones of a fine watercolour … so many small pearls that make Véronique a delicious opéra comique."[23] When Véronique opened in London, The Times said that it was hard to refrain from extravagance in praising it, and judged the music delightfully spontaneous and melodious."[24] The Manchester Guardian judged that Messager was the descendant of Offenbach, and scored more neatly and happily than his predecessor. "There should be no doubt of the success of Véronique, and its success could not but serve to raise public taste."[25] The New York Times found Messager's "distinction and facile grace … delicacy of touch … fine musicianship" a welcome change from the usual Broadway attempts at comic opera.[18] After the Australian premiere the critic of The Sydney Morning Herald wrote of "the atmosphere of sunshine, youth and happiness created by the exquisite delicacy of the joyous music" and contrasted it with the "coarser fare of the average English entertainment."[20] RecordingsAn Edison Gold Moulded Record cylinder of parts of the work was made before July 1907.[26] That year extracts were recorded by Jean Périer and Anne Tariol-Baugé, who had created the roles of Florestan and Agathe in 1898. There are also recordings of extracts by Yvonne Printemps, with Jacques Jansen and an orchestra led by Marcel Cariven, reissued on Gramo LP, DB 5114. More complete efforts are as follows:

FilmA film of the opera (in French) was made by Robert Vernay in 1949, with Giselle Pascal, Jean Desailly, Pierre Bertin and Noël Roquevert among the cast.[27] Notes, references and sourcesNotes

References

Sources

External links |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||