|

Albert Stanley, 1st Baron Ashfield

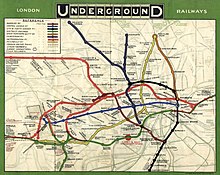

Albert Henry Stanley, 1st Baron Ashfield, TD, PC (8 August 1874 – 4 November 1948), born Albert Henry Knattriess, was a British-American businessman who was managing director, then chairman of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) from 1910 to 1933 and chairman of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) from 1933 to 1947. Although born in Britain, his early career was in the United States, where, at a young age, he held senior positions in the developing tramway systems of Detroit and New Jersey. In 1898, he served in the United States Navy during the short Spanish–American War. In 1907, his management skills led to his recruitment by the UERL, which was struggling through a financial crisis that threatened its existence. He quickly integrated the company's management and used advertising and public relations to improve profits. As managing director of the UERL from 1910, he led the takeover of competing underground railway companies and bus and tram operations to form an integrated transport operation known as the Combine. He was Member of Parliament for Ashton-under-Lyne from December 1916 to January 1920. He was President of the Board of Trade between December 1916 and May 1919, reorganising the board and establishing specialist departments for various industries. He returned to the UERL and then chaired it and its successor the LPTB during the organisation's most significant period of expansion in the interwar period, making it a world-respected organisation considered an exemplar of the best form of public administration. Early life and career in the United StatesStanley was born on 8 August 1874, in New Normanton, Derbyshire, England, the son of Henry and Elizabeth Knattriess (née Twigg). His father worked as a coachbuilder for the Pullman Company. In 1880, the family emigrated to Detroit in the United States, where he worked at Pullman's main factory. During the 1890s, the family changed its name to "Stanley".[1] In 1888, at the age of 14, Stanley left school and went to work as an office boy at the Detroit Street Railways Company, which ran a horse-drawn tram system. He continued to study at evening school and worked long hours, often from 7.30 am to 10.00 pm.[2] His abilities were recognised early and Stanley was responsible for scheduling the services and preparing the timetables when he was 17. Following the tramway's expansion and electrification, he became General Superintendent of the company in 1894.[3][4] Stanley was a naval reservist and, during the brief Spanish–American War of 1898, he served in the United States Navy as a landsman in the crew of USS Yosemite alongside many others from Detroit.[1][5] In 1903, Stanley moved to New Jersey to become assistant general manager of the street railway department of the Public Service Corporation of New Jersey. The company had been struggling, but Stanley quickly improved its organisation and was promoted to department general manager in January 1904. In January 1907, he became general manager of the whole corporation, running a network of almost 1,000 route miles and 25,000 employees.[1][3] In 1904, Stanley married Grace Lowrey (1878–1962) of New York.[1][6] The couple had two daughters:[1][7] Marian Stanley (1906–92)[8] and Grace Stanley (1907–77).[9][10][n 1] Career in BritainRescue of the Underground Electric Railways CompanyOn 20 February 1907, Sir George Gibb, managing director of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL), appointed Stanley as its general manager.[17] The UERL was the holding company of four underground railways in central London.[18] Three of these (the District Railway, the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway and the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway) were already in operation and the fourth (the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway) was about to open.[19] The UERL had been established by American financier Charles Yerkes, and much of the finance and equipment had been brought from the United States. Hence, Stanley's experience managing urban transit systems in that country made him an ideal candidate. The cost of constructing three new lines in just a few years had put the company in a precarious monetary position, and income needed to be increased to pay the interest on its loans.[20] Stanley's responsibility was to restore its finances.  Only recently promoted to general manager of the New Jersey system, Stanley had been reluctant to take the position in London and took it for one year only, provided he would be free to return to America at the end of the year. He told the company's senior managers that the company was almost bankrupt and got resignation letters from each of them post-dated by six months.[21][22] Through better integration of the separate companies within the group and by improving advertising and public relations, he was quickly able to turn the fortunes of the company around,[1] while the company's chairman, Sir Edgar Speyer, renegotiated the debt repayments.[20] In 1908, Stanley joined the company's board and, in 1910, he became the managing director.[1] With Commercial Manager Frank Pick, Stanley devised a plan to increase passenger numbers: developing the "UNDERGROUND" brand and establishing a joint booking system and co-ordinated fares throughout all of London's underground railways, including those not controlled by the UERL.[4] In July 1910, Stanley took the integration of the group further, when he persuaded previously reluctant American investors to approve the merger of the three tube railways into a single company.[23][24] Further consolidation came with the UERL's take-over of London General Omnibus Company (LGOC) in 1912 and the Central London Railway and the City and South London Railway on 1 January 1913. Of London's underground railways, only the Metropolitan Railway (and its subsidiaries the Great Northern & City Railway and the East London Railway) and the Waterloo & City Railway remained outside of the Underground Group's control. The LGOC was the dominant bus operator in the capital and its high profitability (it paid dividends of 18 per cent compared with Underground Group companies' dividends of 1 to 3 per cent) subsidised the rest of the group.[25] Stanley further expanded the group through shareholdings in London United Tramways and Metropolitan Electric Tramways and the foundation of bus builder AEC.[26] The much enlarged group became known as the Combine.[27] On 29 July 1914, Stanley was knighted in recognition of his services to transport.[28] Stanley also planned extensions of the existing Underground Group's lines into new, undeveloped districts beyond the central area to encourage the development of new suburbs and new commuter traffic. The first of the extensions, the Bakerloo line to Queen's Park and Watford Junction, opened between 1915 and 1917.[19] The other expansion plans were postponed during World War I.[29] GovernmentIn 1915, Stanley was given a wartime role as Director-General of Mechanical Transport at the Ministry of Munitions.[30] In 1916, he was selected by Prime Minister David Lloyd George to become President of the Board of Trade. Lloyd George had previously promised this role to Sir Max Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook), Member of Parliament for Ashton-under-Lyne. At that time, a member of parliament taking a cabinet post for the first time had to resign and stand for re-election in a by-election. Aitken had made arrangements to do this before Lloyd George decided to appoint Stanley to the position instead. Aitken, a friend of Stanley, was persuaded to continue with the resignation in exchange for a peerage so that Stanley could take his seat.[31] Stanley became President of the Board of Trade and was made a Privy Counsellor on 13 December 1916.[32] He was elected to parliament unopposed on 23 December 1916 as a Conservative.[1][33] At 42 years old he was the youngest member of Lloyd George's coalition government.[1] At the 1918 general election, Stanley was opposed by Frederick Lister, the President of the National Federation of Discharged and Demobilized Sailors and Soldiers, in a challenge over the government's policy on war pensions. With the backing of Beaverbrook, who visited his former constituency to speak on his behalf, Stanley won the election.[34] Stanley's achievements in office were mixed. He established various specialist departments to manage output in numerous industries and reorganised the structure of the Board.[26] However, despite previous successes with unions, his negotiations were ineffective. Writing to Leader of the House of Commons and future Prime Minister Bonar Law in January 1919, Lloyd George described Stanley as having "all the glibness of Runciman and that is apt to take in innocent persons like you and me ... Stanley, to put it quite bluntly, is a funk, and there is no room for funks in the modern world."[35] Stanley left the Board of Trade and the government in May 1919 and returned to the UERL. Return to the UndergroundBack at the Underground Group, Stanley returned to his role as managing director and also became its chairman, replacing Lord George Hamilton.[36] In the 1920 New Year Honours,[37] he was created Baron Ashfield, of Southwell in the County of Nottingham,[38][n 2] ending his term as an MP.[n 3] He and Pick reactivated their expansion plans, and one of the most significant periods in the organisation's history began, subsequently considered to be its heyday and sometimes called its "Golden Age".[40][41]  The Central London Railway was extended to Ealing Broadway in 1920, and the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway was extended to Hendon in 1923 and to Edgware in 1924. The City and South London Railway was reconstructed with larger diameter tunnels to take modern trains between 1922 and 1924 and extended to Morden in 1926.[19] In addition, a programme of modernising many of the Underground's busiest central London stations was started; providing them with escalators to replace lifts.[42] New rolling stock was gradually introduced with automatic sliding doors along the length of the carriage instead of manual end gates.[43] By the middle of the 1920s, the organisation had expanded to such an extent that a large, new headquarters building was constructed at 55 Broadway over St James's Park station.[44] In this, Ashfield had a panelled office suite on the seventh floor.[45] Starting in the early 1920s, competition from numerous small bus companies, nicknamed "pirates" because they operated irregular routes and plundered the LGOC's passengers, eroded the profitability of the Combine's bus operations and had a negative impact on the profitability of the whole group.[46] Ashfield lobbied the government for regulation of transport services in the London area. Starting in 1923, a series of legislative initiatives were made in this direction, with Ashfield and Labour London County Councillor (later MP and Minister of Transport) Herbert Morrison, at the forefront of debates as to the level of regulation and public control under which transport services should be brought. Ashfield aimed for regulation that would give the UERL group protection from competition and allow it to take substantive control of the LCC's tram system; Morrison preferred full public ownership.[47] Ashfield's proposal was fraught with controversy, The Spectator noting, "Everybody agrees that Lord Ashfield knows more about transport than anyone else, but people are naturally loth to give, not to him, but to his shareholders, the monopoly of conveying them."[48] After seven years of false starts, a bill was announced at the end of 1930 for the formation of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB), a public corporation that would take control of the UERL, the Metropolitan Railway and all bus and tram operators within an area designated as the London Passenger Transport Area.[49] As Ashfield had done with shareholders in 1910 over the consolidation of the three UERL controlled tube lines, he used his persuasiveness to obtain their agreements to the government buy-out of their stock.[50]

The Board was a compromise – public ownership but not full nationalisation – and came into existence on 1 July 1933.[52] Ashfield served as the organisation's chairman from its establishment in 1933 on an annual salary of £12,500 (approximately £600,000 today),[53][54] with Pick as Chief Executive. The opening of extensions of the Piccadilly line to Uxbridge, Hounslow and Cockfosters followed in 1933.[19] On the Metropolitan Railway, Ashfield and Pick instigated a rationalisation of services. The barely used and loss-making Brill and Verney Junction branches beyond Aylesbury were closed in 1935 and 1936.[55] Freight services were reduced and electrification of the remaining steam operated sections of the line was planned.[56] In 1935, the availability of government-backed loans to stimulate the flagging economy allowed Ashfield and Pick to promote system-wide improvements under the New Works Programme for 1935–1940, including the transfer of the Metropolitan line's Stanmore services to the Bakerloo line in 1939, the Northern line's Northern Heights project and extension of the Central line to Ongar and Denham.[57][n 4] Following a reorganisation of public transportation by the Labour government of Clement Attlee, the LPTB was scheduled to be nationalised along with the majority of British railway, bus, road haulage and waterway concerns from 1 January 1948. In advance of this, Ashfield resigned from the LPTB at the end of October 1947 and joined the board of the new British Transport Commission (BTC) which was to operate all of the nationalised public transport systems. At nationalisation, the LPTB was to be abolished and replaced by the London Transport Executive (LTE). Lord Latham, a member of the LPTB and the incoming chairman of the new organisation, acted as temporary chairman for the last two months of the LPTB's existence.[58] The BTC required office space, and as one of his last acts before leaving the LPTB for the BTC, Ashfield offered the use of the eighth and ninth floors of 55 Broadway for the BTC's use. He was in turn allotted a BTC office on one of these floors, but decided to continue using his seventh-floor suite for his BTC duties. Latham, as his replacement at the LPTB (and subsequently the LTE), was not able to occupy this accommodation until Ashfield's death.[59] Other activitiesIn addition to his management of London Underground and brief political career, Ashfield held many directorships in transport undertakings and industry. He helped establish the Institute of Transport in 1919/20 and was one of its first presidents.[60] He was a director of the Mexican Railway Company and two railway companies in Cuba and a member of the 1931 Royal Commission on Railways and Transportation in Canada.[1][61] He was one of two government directors of the British Dyestuffs Corporation, its chairman from 1924 and was involved in the creation of Imperial Chemical Industries in 1926, of which he was subsequently a non-executive director. Ashfield was a director of the Midland Bank, Amalgamated Anthracite Collieries and chairman of Albany Ward Theatres, Associated Provincial Picture Houses, and Provincial Cinematograph Theatres.[1] During World War I, he was Colonel of the Territorial Force Engineer and Railway Staff Corps and was Honorary Colonel of the Royal Artillery's 84th Light Anti Aircraft Regiment during World War II.[61] PersonalityBiographers of Stanley characterise him as having an "immensely active mind, and a strong sense of public duty" and a "great charm of manner and a sense of humour which concealed an almost ruthless determination" that made him a "formidable negotiator".[1] His "intuitive understanding of his fellow men" gave him "presence, which allowed him to dominate meetings effortlessly" and "inspired loyalty, devotion even, among his staff".[62] He was "a dapper ladies' man, something of a playboy tycoon, who was always smartly turned out and enjoyed moving in high society".[63] Legacy

Ashfield died on 4 November 1948 at 31 Queen's Gate, South Kensington.[1] During his near forty-year tenure as managing director and chairman of the Underground Group and the LPTB, Ashfield oversaw the transformation of a collection of unconnected, competing railway, bus and tram companies, some in severe financial difficulties, into a coherent and well managed transport organisation, internationally respected for its technical expertise and design style. Transport historian Christian Wolmar considers it "almost impossible to exaggerate the high regard in which LT was held during its all too brief heyday, attracting official visitors from around the world eager to learn the lessons of its success and apply them in their own countries." "It represented the apogee of a type of confident public administration ... with a reputation that any state organisation today would envy ... only made possible by the brilliance of its two famous leaders, Ashfield and Pick."[65] A memorial to Ashfield was erected at 55 Broadway in 1950[n 5] and a blue plaque was placed at his home, 43 South Street, Mayfair in 1984.[66] A large office building at London Underground's Lillie Bridge Depot is named Ashfield House in his honour. It stands to the south of the District line tracks a short distance to the east of West Kensington station and is also visible from West Cromwell Road (A4). Memorial at 55 Broadway Transport for London's Ashfield House in West Kensington Blue plaque at 43 South Street, Mayfair Memorials to Lord Ashfield Notes

References

Sources

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||